Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 2 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

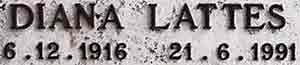

Diana Lattes (1916-1991) |

Diana Lattes (1916-1991) |

Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity

Terry Smith

Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity (Part 1)*

A park in Istanbul during the autumn months of 2001: out from the manicured grass protrudes the corner section of a new, white-walled building. Or is it sinking (fig. 1)? High modernist styling like that can only mean one thing: art gallery. But for what kind of art, and why is it here? Walk around it and the words Temporary Art appear above the blocked, nearly inaccessible door. Of course: a gallery or museum of contemporary art. Yet its duck-rabbit directionality is a puzzle. Are we meant to construe it as the victim of some unfelt earthquake, historical tragedy, or human neglect? Or perhaps is it emerging from underground, an architectural chrysalis taking, triumphantly, its rightful shape?

The answer is left deliberately ambiguous. The creators of this piece of public art, Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, made it for the Seventh Istanbul Biennale; the park is a part of the exhibition grounds. So it is, first of all, what the words on it lightheartedly say it is: a temporary work of art. In other projects by these artists, architectural forms and functions are altered in subtle and amusing ways. In one case, they installed a diving board so that it pointed out the window of an upper story in a modernist high rise. For a work entitled SPECTACULAR2003 the Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf underwent the transformation of having its entire collection dismantled, packed into trucks that were driven once around the building, then reinstalled exactly as before. In the same year Elmgreen and Dragset installed a white truck with a caravan as if it had shot through from the other side of the planet and erupted, jackknifed, at the main crossing of the Galleria, Milan, entitling this work Short Cut. In Istanbul, however, the artists offered an instalment from their Powerless Structures series; the subsiding/ projecting museum is subtitled Traces of a Never Existing History, Figure 222, as if it were an illustration from a future archaeology of the present. The artists are wittily proposing that contemporary art is concerned with posing questions, usually about itself, perhaps without much hope of effect, and destined to end in ambiguity. Contemporary art might, somehow, be losing touch with time. Yet this work, like many of their others, is potent: smartly styled, conceptually compact, formally pointed, easy to get, hard to forget. Such a contradiction between surety of form and uncertainty as to content is a hallmark of art in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It prompts the question, Just what is so contemporary about this kind of apparent contradiction, and why does it pervade art these days?

fig. 1. Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, Powerless Structures - Traces of a Never Existing History, Figure 222. Mixed media, 2001 (at Istanbul Biennale).

What Is Contemporary Art Now?

For more than two decades no one has articulated a successful generalization about contemporary art. First there have been fears of essentialism, followed by the sheer relief of having shaken off exclusivist theories, imposed historicisms, and grand narratives, and then, recently, delight in the simple-seeming pleasures of an open field. More prosaically, the answer has seemed obvious to the point of banality. Look around you. Contemporary art is most—why not all?—of the art that is being made now. It cannot be subject to generalization and has overwhelmed art history; it is simply, totally contemporaneous. But this pluralist happymix is illusory. The question of contemporary art has, in fact, been insistently answered more narrowly by the acts of artists and the organizations that sustain them—so much so that these responses are, by now, deeply embedded in both. (Buried in each other, according to Elmgreen and Dragset.) The responses do not have singular shape; rather, they embody tendencies towards both closure and openness. Most accounts highlight the currency of one or another aspect of current practice: new media, digital imagery, immersive cinema, national identifications, new internationalism, disidentification, neomodernism, relational aesthetics, postproduction art, remix cultures. The list keeps extending. Apologists stress the pivotal connectedness of their favored approach to at least one significant aspect of contemporary experience, but usually deny any claims to universality, sighing with relief that the bad old days of exclusionary dominance are over.[1]

Nevertheless, it seems to me that, in visual art discourse, two big answers have come to figure forth amidst the multitude of smaller ones. This is especially evident in the major world art distribution centers. From broader world perspectives, however, their prominence is misleading and, perhaps, self-defeating. The multitudes may be on the cusp of having their day.

fig. 2. Richard Serra, Double-Torqued Ellipse. Cor-Ten steel, 1997. Dia Art Foundation. 2000. Installation view at Dia:Beacon, Hudson River, New York.

Ambitious, big-picture interpretations aim—as they always have—to be acute descriptions of how particular (artistic) practices relate to general (social) conditions. I present them, mostly, in my own terms, for this is a polemic as much as it is a description. I will offer characterizations of two great forces, in all of their mismatched contention. I will then show them to be polarities of a dichotomous exchange, the central regions of which are occupied by a mainstream that is, paradoxically, dispersive: the spilling diversity of contemporary practice.

Contemporary as the New Modern

Richard Serra was a leading proponent of informal art, capturing, in pieces as various as videos showing his hand clutching at falling lead and his Verb List (1967–68), its commitment to artwork as a demonstration of active process rather than the realization or termination of a preconception. He soon developed a powerful strategy for building this kind of dynamism into works that seem, at first, as reductive and self-contained as most minimal sculpture but that draw the spectator into a much more engaged relationship. This energy flows from their size, their evident weight, from the eccentricity of their angles and the precariousness of their positioning—all qualities that are exact in relation to each observer’s mobile eyes and body. Unlike the virtual spatialities of abstract sculpture in the constructivist mode, but like happenings and environments, Serra’s sculptures require one to walk close to, around, or through them, in quite specific ways. Huge sheets of unfinished Cor-Ten steel are stacked up as the only support of each other, in busy public spaces such as the town center of Bochum, Germany (Terminal [1977]), or at Broadgate, outside the entrance to the London Stock Exchange (Fulcrum [1986–87]). Tilted Arc, a 120-foot-long partial cylinder of raw Cor-Ten steel, over two inches thick and twelve feet high, installed in the Federal Plaza, New York, in 1981, provoked a controversy fierce enough to lead to its removal.[2]

fig. 3. Matthew Barney, Cremaster 3, 2002. Production still from film, showing Richard Serra as Grand Master.

More than any other artist’s work, and not least in its shift back through art historical time, Serra’s has come to represent what late modern sculpture means within the frameworks of official contemporary art. At the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Frank Gehry shaped the famous “fish” gallery around Serra’s Snake. When, in 2003, dia:Beacon opened in a converted factory on the Hudson River, New York, the railroad shed and loading dock were filled by Serra’s three gigantic Torqued Ellipses and the single steel slab constituting his Torqued Spiral (fig. 2). In their clarity of form as read by the moving body, and in their muscular dialogue with their surroundings, these works have a command of space that is exceptional in its resolute clarity. In such a context, however, older conceptions of museum display— art’s history, schools, and movements—are banished in the wow! of the aesthetic encounter in its distilled form. In elevating this instantaneity towards awestruck transcendence, the Dia:Beacon displays shift the trenchant spatiality of minimalism at its best towards a peculiarly late modern version of pure contemporaneousness. In the words of Dia founder Heiner Friedrich: “Art has no history—there is only a continuous present. . . . The non-stop presence of art! Velázquez, Goya, Manet are all in one line, which extends to Matisse and Warhol. If art is alive, it is always new.”[3]

During the 2003 exhibit of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, the famous rotunda spiralled up and away from sight, into a chaste light, whiter than usual. A corporate logo hovered above the skylight; the lozenge shape seemed familiar, but what was that brand? Cobalt blue swam up from beneath one’s feet. Pink patches, bright banners and competing noises composed a swirling panorama. From every side and above, particularly on the giant, five-screen Jumbotron, video monitors flashed out images of fantastical yet clearly fashionable characters involved in high-speed action or ritually sedate posing. Punk rock exploded through attenuated sounds, crescendos surged out of ambient Muzak. It was, at once, an extraordinary work of art, an art theme park, and a daring mix of far-out art, music video, cool design, and high-tech and crossover fashion that for an entire generation is definitive of contemporary experience. The Cremaster cycle takes the form of five feature-length 35mm films and a growing number of videos, drawings, collages, sculptures, and installations that relate directly to the films—a mobility of medium typical of all forms of contemporary art. Typical, too, is the esoteric portentousness of its central idea: the cremaster is the muscle that governs the chromosome switch from female to male and then controls testicular contraction. Ambiguous kernel, assured shell—again. Its $8 million production costs were, for the time, exceptional.[4]

The films narrate an elaborate, self-enclosed allegory. Set in Bronco Stadium, Boise, Idaho, the artist’s hometown, Cremaster 1 (1995) tracks a troupe of dancers who take the shapes of still-androgynous gonads, symbolizing pure potential. Cremaster 2 (1999), set in the Canadian Rockies and Utah, connects three themes entailing movement backwards in time: the movement of glaciers, the stories of murderer Garry Gilmore and of escapologist Harry Houdini, and the lives of drone bees. Cremaster 3 (2002) connects the construction of the Chrysler Building to that of Solomon’s Temple and provides a setting for an escalating clash between Hiram Abiff, architect of Solomon’s Temple and archetypal Master Builder in the Masonic Order (played by Serra), and the Entered Apprentice (played by Barney) (fig. 3). Surmounting the five levels of initiation into the Masonic rites drives this episode, as well as the interlude (subtitled The Order) in which Barney overcomes complex obstacles at each level of the Guggenheim Museum’s rotunda, themselves now symbolic of each of the films in the Cremaster cycle. Set on the Isle of Man, Cremaster 4 (1994) stages a motorcycle race between two teams travelling in opposite directions around the perimeter of the roughly circular island, representing in turn the cremaster muscle ascended, thus undifferentiated but tending to the feminine, and the muscle descended, thus tending to differentiation and the masculine. The teams are, however, symbolically tied to each other. Descension is finally attained in Cremaster 5 (1997). Set at key sites in Budapest—the Lánchíd (Chainlink) Bridge, the Opera House, and the Gellért Thermal Baths—it performs, as if in a dream, the longing, despair, and eventual death of the Queen of Chain (played by Ursula Andress) and her Diva, Magician, and Giant (all played by the artist).

Despite its complex structure and postmodern stylistics, this is a quest narrative, a search for belonging through places that have their own imperatives amidst physical and social processes that are strangely subject to incessant fusion and separation, isolation and metamorphosis. Although more up-to-date and engaged with media culture, the work requires a relationship to the spectator as direct as it is in Serra’s work. This—the Cremaster cycle claims—is what it is to be in the era of cultural division and genetic engineering. The same spirit of individual battling against unfathomable odds to surrender individuality and achieve community acceptance, the same insatiably active embrace of ultimate passivity, underlies the success of novels and films such as Lord of the Rings and the vast membership, worldwide, of cults, organized religions, and civic organizations. Like them, this spirit makes the Cremaster cycle at once extraordinary and banal.

Works such as these provide the first powerful answer to the question of the nature of art in these times: contemporary art, as a movement, has become the new modern or, what amounts to the same thing, the old modern in new clothes. In its most institutionalized forms—from the triumphalist overreach of the Guggenheim Museum’s global franchising through the Old Master elegance of the installations at Dia: Beacon to the confused gesturing in the contemporary galleries when the Museum of Modern Art, New York, reopened in 2004 - it is the latest phase in the century-and-a-half-long story of modern art in Europe and its cultural colonies, a continuation of the modernist lineage, warily selected not least in an attempt to preserve this cultural balance of power. Official contemporary art resonates with the vivid confidence and the comforting occlusion that comes with it, taking itself to be the high cultural style of its time. Think (as a beginning of a list of the best of it) of not only the work by Serra and Barney but also of Jeff Koons at fifty, the subadolescent consumerlands of Takashi Murakami and Mariko Mori, Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome as distinct from Mad Max, The Matrix Revolutions, Gerhard Richter’s paintings, Andreas Gursky’s scale, Thomas Struth’s subjects and Thomas Demand’s style, Wang Quingsong’s The Night Revels of Lao Li alongside his China Mansion, Damien Hirst’s early work but not the Benneton-advertisement-style return to painting in his 2005 exhibition The Elusive Truth! Tracey Emin’s I’ve Got It All! and so on, through all the major survey exhibitions and the latest sales of contemporary art for record prices.[5] Someone, soon, may baptize it “contemporism”— a contraction, perhaps, of contemporary modernism—or “remodernism”—emphasizing its renovating, recursive character—to predictable scorn followed by eventual acceptance. In architecture, the parallel impulse has recovered an old label: late modern.[6] Better, perhaps, not to name it: like all unspecifiable but deeply desired values, it is more powerful when taken for granted.

* Terry Smith; Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity, Critical Inquiry, Summer 2006, pp. 681-689.

Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity (Part 2)

Notes:

[1] The subtlest presentation of this “de-definitional” perspective during its brief reign was Vad är samtida konst? /What Is Contemporary Art? ed. Peter Edström, Helene Mohlin, and Anna Palmqvist (Rooseum, Malmö, Sweden, 3 June–30 July 1989). In a series of publications beginning in 1984, Arthur Danto sought to define contemporary, as distinct from modern, art as a posthistorical pluralism, most concisely in the introduction to his After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History (Princeton, N.J., 1997). The present essay develops from my What Is Contemporary Art? Contemporary Art, Contemporaneity, and Art to Come (Woolloomooloo, N.S.W., 2001) and “What Is Contemporary Art? Contemporaneity and Art to Come,” Konsthistorisk Tidskrift 71, nos. 1–2 (2002): 3–15.

[2] See Richard Serra Sculpture, ed. Rosalind E. Krauss (exhibition catalog, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 27 Feb.–13 May 1986); Richard Serra, ed. Hal Foster and Gordon Hughes (Cambridge, Mass., 2000); and Richard Serra Sculpture 1985–1998, ed. Russell Ferguson, Anthony McCall, and Clara Weyergraf-Serra (exhibition catalog, Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, 20 Sept. 1998–3 Jan. 1999).

[3] Quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “The Mission: How the Dia Art Foundation Survived Feuds, Legal Crises, and Its Own Ambitions,” The New Yorker, 19 May 2003, p. 46. An earlier, yet quintessentially modernist, version of this kind of aesthetic valuing may be found in the “instantaneousness” that Michael Fried, in his famous 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood,” saw as definitive of a convinced response to modernist art and counterposed to the “theatricality” of minimalism’s address to the spectator (Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews [Chicago, 1998], p. 167).

[4] See Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle, ed. Nancy Spector (exhibition catalog, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 6 June–7 Sept. 2002).

[5] On this topic, see my “Primacy, Convergence, Currency: Marketing Contemporary Art in the Conditions of Contemporaneity” (parts 1 and 2), Art Papers 29 (May–June 2005): 22–27 and (July–Aug. 2005): 22–27.

[6] For a discussion of contemporary architecture parallel to that offered in this article see my The Architecture of Aftermath (Chicago, 2006).