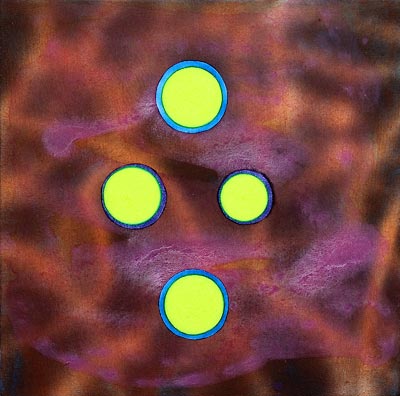

Idea of Creation: Creation from Point Zero

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 2 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

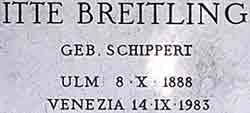

Itte Breitling (1888-1983) |

Itte Breitling (1888-1983) |

Idea of Creation: Creation from Point Zero

Wolfgang Welsch

At Point Zero of Creation*

The Problem of Beginning

The problem of beginning is common to many artists. We can easily imagine an artist sitting in front of a white sheet of paper or an empty canvas unable to begin her work—maybe for hours. The first stroke, the first tinge of color, the first note would in a sense decide everything. It will provide the artist with possibilities but also exclude endless amounts of other possibilities. How shall she make this decisive step? Where from shall she take the certainty for it? Hence, the inhibition of the artist in the beginning—at point zero of creation.

We know this problem especially from modernity. Van Gogh wrote to his brother, “You don't know how paralyzing that is, that stare of a blank canvas, which says to the painter, ‘You can't do a thing’. The canvas has an idiotic stare and mesmerizes some painters so much that they turn into idiots themselves. Many painters are afraid in front of the blank canvas.”[1] We also know that Cézanne often spent hours sitting motionless in front of a canvas before making the first stroke.[2] The phenomenon is also well known in the cultural area of Asia.[3]

But once the first move has been made, things are becoming easier. The first step provides further possibilities of continuation. Subsequently, one thing will lead to the next. A drive originates that almost automatically leads the artist onwards. The start has been extremely difficult; the continuation is easy in comparison.[4] The only thing that matters now is that the artist is capable of giving in to the logic of the originating work. If she succeeds in doing so, her work will unfold all by itself. (Only stopping in time can then be a problem.)

Historical Limitations

Of course, beginning isn’t an issue in every artistic discipline and at every point in time, but only under certain circumstances and in certain epochs. If there are canonical standards and guidelines with respect to topics, ways of representation or procedures, the problem does not exist. Such was the case in the art of ancient Egypt or in the medieval tradition of depicting saints. Where standards are to be fulfilled, the first steps are already made by the canon itself. Actually, everything is ready at hand there, nothing to invent or create. The artist only has to realize the canonical guidelines in the individual case.

In short, the problem of beginning arises only if the beginning shall be an absolute beginning, if the creation shall be a creation without preconditions and guidelines, if it is meant to bring forth a new world all by itself; or if it is an essential part of the canon to come up with individual, artistic variation, as it is the case in the European history of arts since artistic subjectivity became a standard in the Renaissance. In the fully developed modernity, the problem of beginning became increasingly important due to a more intense focus on individuality and subjectivity. Not by chance are all of the examples mentioned above artists that were working at the end of the 19th and throughout the 20th century.

An Utterly Impossible Ideal?

But now let us survey the idea of absolute creation, of creation from point zero. Isn’t it essentially paradoxical? Isn’t the mere idea of pure creation amiss from the outset? There are always numerous preconditions ranging from the artist’s personal experiences, and her belonging to artistic groups and movements, to the fact that the history of art itself and the development of art as a social institution have preceded her artistic practice. All this adds to the formation of an indispensable context. How can creation ab ovo then be possible? How can the artist start from scratch? Her work will always rest on a voluminous congregation of preconditions.

Artists that take pure creation as their aim are fully aware of this problem. Often they express the need to get rid of the burden of tradition and to leave behind all guidelines before they can start working. They claim the necessity to forget and to become empty (here the Western statements remind us of a well known East-Asian topos). Cézanne, for example, said that the painter’s “entire will must be silent.” The painter “must silence all prejudice within himself. He must forget, forget, be quiet, be a perfect echo.”[5] In Chinese aesthetics it is a widespread opinion that “the artist can only be able to create an outstanding work of art if he forgets his intention, his proficiency, his rules and maybe even his artistic skills.”[6]

The Theoretical Background and Foundation of the Idea of Absolute Creation

Why do artists pursue the ideal of absolute creation, even though it is sheer impossible to live up to it? What is the driving idea behind it?

a. The Christian Conception of Creatio ex nihilo and its Limitations

The answer is plain in Western culture (and probably the ideal of starting creation from point zero is an essentially western ideal, I will come back to this later on). The decisive topos is the Christian concept of creation. Here, creation is conceived as creatio ex nihilo. Following this, artistic creation has on various occasions been understood in analogy to God’s creation. In this sense, Leonardo da Vinci, for example, thought of artists as the “relatives of God.”[7]

Of course, the Christian idea of creation is afflicted with some problems. Obviously the conception does not really equal the formula of creatio ex nihilo since creation does not simply follow from nothing, but has a very important precondition: God. He is supposed to exist prior to all creation, and only because of his existence creation can unfold. In so far, the Christian idea of creation does not really conceive creation as such, but solely the creation of the world and not of God. It is, so to say, an incomplete conception of creation unsuited to serve as model for absolute and full creation. The idea of an absolute creation would also have to incorporate the emergence of God.[8]

Apart from that, the Christian conception of creation is different from the artistic idea of creation from point zero in so far as God’s creation is meant to mirror God himself, to be a manifestation of his perfection.[9]

Here, creation is thought of as a reflex of its own foundations. Hence, the artistic and the Christian ideal differ in two respects: what counts for the artist is absolute freedom from any pre-established restraints, and her work shall only stand for itself, not reflecting anything else. At first, one might have thought that divine and artistic creation have a common ground in so far as both presuppose a maker (God on the one hand and the artist on the other) but the big difference is that God wants to express himself while the artist wants to bring forth something different from herself, something genuinely new. In this respect, the artistic idea of pure creation exceeds the Christian conception of creation. The latter cannot be considered a sufficient model for the first.

b. Cosmic Evolution as the Archetype of Creation from Point Zero

Now, does this mean that the artistic ideal of creation devoid of any restraints has no antetype at all, that nothing compares to it or even excels it?

No, because we know at least one process that fulfills the criteria mentioned before, a process that has no restraints and that generates all of its forms and contents solely from its own progression. What I mean is, of course, the one process through which everything came into being and that everything belongs to: the process of cosmic evolution.

The “Big Bang” literally started from nothing (in physical terms: the “vacuum”) and ignited a dynamic owing to which everything came into being. All of this occurred without any pre-established guideline or program, but in a strictly autogenetic manner. Cosmic evolution is a process of absolute creation. It does not have the form of the development or unwinding of something that has been (archetypically or logically) drafted or preprogrammed. Cosmic Evolution does not realize predetermined conceptions. Rather, it creates everything – the real and the ideal, the material and the logical – in an absolutely autonomous and autogenetic manner. In short, cosmic evolution really represents a creatio ex nihilo, a creatio ab ovo, a creation from point zero.[10]

And here the parallels to the work of the artist are obvious: the initial cosmic state of absolutely equal distribution and symmetry accords to the white sheet of paper; the minimal break in symmetry brought about by the Big Bang (understood as an effect of quantum fluctuations) parallels the first installment of a distinction within the artistic work. And as one step continually led to the next in cosmic evolution bringing forth a giant self-energizing process, so one step consequently leads to the next in artistic creation.[11]

Depotentialization of Point Zero Ambitions

If the great model at the basis of artistic creation from point zero is evolution, what repercussions will this insight have on the creative ideal?

First of all, one will realize that one’s own creation, even though it might appear grand and successful, is infinitely small—sheer nothing—in comparison to cosmic creation. Even the best realization of the extreme artistic ideal of absolute creation must appear poor taking the cosmic model into account. So modesty rather than great expectations is appropriate. One has to give up on the pathos connected with absolute creation. Even the most genuine artistic production can at best be a distant echo and pale imitation of the long foregone and greater cosmic creation. The artistic idea of creation from point zero that originally was supposed to represent the maximum of creativity turns out to be irrelevant and insignificant in comparison to the true maximum.

In addition, it becomes clear that the structure at the core of the initial idea is not sustainable. The essential condition of being devoid of antecedents cannot be fulfilled – rather artistic productivity will forever and insurmountably be grounded on one grand condition, namely the course of cosmic evolution without which there would be neither earth, nor human societies, nor the institution of art. Neither the artist nor the work of art would be in existence.

Thus, the idea of creation from point zero breaks down. Even the most genuine artistic creation is merely secondary and dependent in comparison with cosmic evolution. From this point onwards, one has to conceive and interpret artistic creation differently – and probably search for a new approach in artistic practice too.

Due changes: Concepts of Artistic Activity Taking Evolution into Account

From now on, the artist can no longer understand her work just in the context of art alone, but must perceive it as a happening in the context of evolution. She will have to see her activity as belonging to and rooted in the most archetypical creative process there is: evolution.

But how can we further specify art within the scope of evolution? Being a moment in the course of evolution can be said pretty much of everything—of an earthquake, of road traffic, or of the happenings in the course of an evening with the family. How can art still or again stand out as something unique if we adopt, as it appears to be necessary, the perspective of evolution? Perhaps cultivating a special relationship with evolution's typical creative character is an option here. There are several possibilities to do so.

a. Art as an Analogy for Creation

A first one is the attempt of art to express the creativity of evolution. Surely the latter can not be depicted directly. But one can develop analogous ways of operating in the field of art that reflect and express the creativity of evolution, or one can even try to get in contact with the ultimate source of creation. What has happened on a large scale in evolution shall micrologically be repeated within the work of art.

In this sense, Paul Klee spoke of art as a “simile of creation” i.e. of “God's work.”[12] For him, “the relation of art to creation is symbolic. […] Art is an example just as the earthly is an example of the cosmic.“[13] Basically, this was the central thought in Romanticism. Romantic art was not concerned with the depiction of nature as it appears to us, but with capturing its innermost core, the active source at the bottom of all natural appearance as such: natura naturans.

Artists following this line of thought do not see themselves as autonomous makers but as a vessel or medium in which nature itself is at work.[14] To put it with Paul Klee again, “We are charged by this force even in our smallest parts.”[15] The artist wants to contact and embrace the wellspring of being and finally become a direct agent of nature’s origin.[16]

b. Characteristic Features of Evolution as Central Ideas in Artistic Work

To commit oneself to the idea of modeling one’s own artistic work on the prototypical creative model of evolution might as well—and in a less lofty way than by trying to get in to contact with the primordial source of nature—be done by taking essential characteristics of the evolutionary processes as central themes of the artistic expression and way of working. In this sense, the artist can, for example, choose chance and self-organization as guiding principles.[17] In this way, art still operates analogously to nature, but now by expressing nature’s typical features and creating awareness for them. The main concern is not the actual work of art but the expression of and reflection on the prototypical kind of creativity, the non-artistic creativity of evolution.

c. Art Operates Like Nature—Nature Creates Art

Finally, the plain appearances of nature (rather than the source of creation and essential features of evolution) can become the point of orientation for the artistic attempts. Instead of the concept of naturata naturans, natura naturata is getting the center of focus here. The aim is to let things evolve within the work of art just as they do in reality: freely, on their own, and without being arranged and dictated by the artist.

In this sense, Emil Nolde admitted, “In painting I always hoped that through me, as the painter, the colors would take effect on the canvas as logically as nature herself creates her configurations, as ore and crystals form, as moss and algae grow, as flowers must unfold and bloom under the rays of the sun.”[18] Cézanne followed the same line of thinking when, after demanding that the artist “must silence all prejudice within himself" and become a “perfect echo”, he declared that “then the full landscape will inscribe itself on his photographic plate.”[19] Likewise, Morton Feldman did not want his works to be like mere objects but rather like evolving things.[20]

One can come up with an even more extreme version of this thought by cherishing the idea that it is nature itself that procreates the work of art. This conception has been around for centuries. One can find it, for example, during Renaissance in Leone Battista Alberti[21] and in the 20th century in Max Ernst.[22] Here, the appearances are meant to bring forth the work of art. The artist only is the medium by means of which nature produces a representation of itself.[23]

The New Point Zero of Creation: the Dissolution of the Creative Ideal

Let us take a look back. Which steps have we gone through so far? First of all, there was an increasing dissociation from the artistic ideal of absolute creation in the sense of a creation starting from point zero. The insight that there cannot be a point zero for the artist since the great creation of evolution precedes any artistic endeavor was the decisive point that necessitated a break. It forced the artists to give up the claim on an autonomous creation and take over a perspective that sees their work situated within the evolutionary process itself. At this point three possibilities unfold themselves. (a) The artist can orientate herself towards the origin of all creation and perceive herself as its successor. Thereby, she can at least in a modified form stick to the creative pathos with the sole difference that the creation is actually not her own but that of evolution. (b) Or the artist can restrict herself to expressing typical process modes of evolution such as self-organization and contingency.[24] (c) Or the artist can let go of all these high flown claims and dedicate her whole work to the sheer appearance of nature and depict the emergence of its elements. At this point we cannot talk of a creation on the side of the artist anymore. Art at this stage is merely bringing about a reproduction i.e. it is not constructing but reconstructing at best.

Thus, we have reached a new type of “point zero of creation”: the negation of artistic creation as such. Originally “point zero of creation” meant the ideal of artistic work as a grand and free endeavor creating new worlds. Now, we have reached the end of this ideal and its claims. It has shrunken to zero.[25]

Contemporary Art: Beyond Creation

To me, the dismissal of the old-modern idea of creation seems to a large extent to be characteristic of contemporary art.[26] One does no longer intend to create works that are meant to stand for themselves. Rather, the artist tries to intervene in a context, to transform what is at hand, or to produce contingent and ephemeral things that, so to say, fully realize themselves in their disappearance. Today not only good design but good art as well is increasingly becoming invisible.[27] This, then, might have been the general course of art in modernity and in the transition into a hereafter of modernity: that art at first sophisticated creation, but in the end merged into a state of no-longer-creating.

West and East

It seems to me that this contemporary artistic attitude comes closer to East Asian ideas than the modern pathos of creation. The latter was a typically Western phenomenon anyway. The world is creation and the artist shall be a creator. This standard model has been deeply entrenched into Western brains. In the East, on the contrary, the idea of creation from point zero has no base. It appears to be completely amiss. In Asia one doesn’t count on creation but on articulation. The artist does not understand herself as the creator of a world but as an agent, a tool and a part of the world. Her work makes nature visible. And she finds delight in the fact that in her practice nature is coming even more to itself, is becoming more lucid than it was in its worldly appearance.

If this is true, then I would not only have depicted how the Western idea of creation falls apart, but also how the Western way of thinking about art is merging with the Eastern idea of non-creation. —Or is this only half the truth? Isn’t there a movement directly opposing to this? Isn’t it the case that Asian artists today take up the Western ideal of creation (that Western artists have dissociated themselves from)? Isn’t it a fact that today, all of sudden, Asian artists wants to ‘create’? Is, thus, —in this and perhaps also in other respects—the West preserved in the East, and the East in the West?

(Translated by Gregor Stöber)

* Wolfgang Welsch; At Point Zero of Creation, Yearbook of Aesthetics, Volume 14, 2010, pp. 200-213.

Notes:

[1] Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, October 1884, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, trans. Arnold J. Pomerans, ed. Ronald de Leeuw. (London: Penguin Classics, 1998) 281.

[2] Maurice Merlau-Ponty, “Cézanne‘s Doubt,” in: Basic Writings, ed. Thomas Baldwin (London: Routledge, 2004) 279.

[3] Tschang-Tsi, a Chinese Philosopher living around 800 AD, wrote the following poem entitled The White Sheet of Paper:

“My head heavy hanging in my hands, I stare

On the white sheet of paper that remains

As empty as it was ever since it is lying in front of me.

I stare at the ink slowly drying on my brush,

My soul is asleep.

When will you wake up, soul of mine?

I jump up and hasten to the plain

On which the sun glows; I silently let

The hands glide over the high grass,

Above this place lies the forest, like velvet

There the graceful line of mountains,

The snow of which the sun covers in roses

I see the clouds floating in the blue,

Full of hope I return home, no sooner than

The ravens gloatingly screech their laughter past me.

And again I sit in front of the white sheet of Paper

And, with my head hanging in shame, I stare on it

Alas! The paper remains empty as it was before.”

[4] From the philosophical perspective Hegel and Spencer Brown are suggesting themselves for the elucidation of the “problem of beginning”. Hegel has shown that the actual beginning can neither lie in the being nor in the nothing for these two initially are totally indifferent. (And therefore can very well be compared to the white sheet of paper, resp. the white canvas.) Rather the beginning happens in the transition to becoming, and as soon as this is done, everything unfolds until the end in coherent consequence. Spencer Brown made clear that the primal action is the “drawing of a distinction” from which all the subsequent distinctions follow. By the way, here we find an interesting relation to the Dao De Jing: Spencer Brown placed the third line of the first chapter of the Dao De Jing (in Chinese script) in front of the main text of his Laws of Form: “Inconceivable are Heaven's and Earth's Origin.” This line is then followed by the famous formula “drawing a distinction.”

[5] Conversations with Cézanne, ed. Michael Doran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001) 111.

[6] Feng Peng, “On the Modernisation of Chinese Aesthetics,” in: Asian Aesthetics, ed. Ken-Ichi Sasaki (Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2010) 139-154, here 144. Analogously we read in the Dao De Jing that, “great music nearly has no notes, the great picture is devoid of form” [Chap. 4]. Cp. also the famous metaphor of Yan Yu (ca.1180-1235) according to which the traces of conscious artistry hide themselves like a gazelle that hangs herself into a tree by her horns to sleep; the hounds may detect her scent, but they cannot find her out.

[7] Leonardo da Vinci, Trattato della pittura [Reprint of Codex Vaticanus Urbinas 1270] (Neuchâtel: Le Bibliophile) 11 [8]. – By the way, already Nicholas of Cusa pointed out that every production of artifacts by humans comes close to divine creativity: “A spoon has no other exemplar except our mind's idea. […] forms of spoons, dishes, and jars are made by human artistry alone. So […] artistry involves the making, rather than the imitating of created visible forms, and in this respect it is more similar to the Infinite Art.” (Nicholas of Cusa, Idiota de mente – Der Laie über den Geist [1450 written, 1488 published], in: idem, Philosophisch-theologische Werke, Vol. 2. Hamburg: Meiner, 2002.15 [II, 62]).

[8] In addition, the Christian idea of creation is not devoid of any restrictions and defaults even if one neglects the condition of the existence of God himself for a second. Since God produces, so to say, within himself the ground plan i.e. the structure and logic of the world as well as its archetypes, the actual creation boils down to the material realization of the ideal forms designed beforehand. This is why Hegel (maybe not fully in conformity with his own line of thinking but consistent with the Christian idea of creation) could declare that the logic designed by him is “the exposition of God as he is in his eternal essence before the creation of nature and a finite mind.” (Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Science of Logic, London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1969, 50) By the way, it is for the preexistence of the archetypes that God could suffer the mishap which Plato described in his dialogue Protagoras with regard to Epimetheus and which Pico della Mirandola picked up in his De dignitate hominis: God depletes the supply of archetypes before he goes about the creation of mankind and therefore needs to find a makeshift.

[9] God is supposed to have created the world and especially us human beings “in his own image” (Genesis I, 27). And the purpose of our cognitive faculty lies in perceiving and praising God's glory in view of his creation, “The Creator-Intellect makes himself the goal of his own works in order for his glory to be manifested; he creates cognizing substances that are capable of beholding his reality.” (Nicholas of Cusa, “De Beryllo,” trans. Jasper Hopkins. in: Nicholas of Cusa: Metaphysical Speculations, Minneapolis: Arthur J. Banning Press, 1998.)

[10] Cp. Wolfgang Welsch, “Absoluter Idealismus und Evolutionsdenken,” in: Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes. Ein kooperativer Kommentar zu einem Schlüsselwerk der Moderne, Eds. Klaus Vieweg, Wolfgang Welsch (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2008) 655-688.

[11] By the way, there is a temporal relation between the emergence of the scientific idea of evolution and the development of the artistic ideal of creation without antecedents. The scientific idea of Evolution (first of cosmic and then of biological evolution) came up between 1750 and 1850, and soon after that creation from point zero became a central theme in the fine arts.

[12] Paul Klee, “Redigierte Tagebuchnotizen für Otto Zoff, ” in: Paul Klee, Tagebücher 1898-1918 (Stuttgart: Hatje 1988), 518; resp. Paul Klee, “Wege des Naturstudiums” [1923], in: idem, Das bildnerische Denken (Basel: Schwabe 31971) 63-67, here 67.

[13] Paul Klee, “Schöpferische Konfession” [1920], in: idem, Das bildnerische Denken (Basel: Schwabe 31971) 76-80, here 79.

[14] Cp. Gustav Mahler: “Just imagine a work of such magnitude that it actually mirrors the whole world — one is, so to speak, only an instrument, played on by the universe” (Gustav Mahler, letter to Anna von Mildenburg, June or July 1896, in: Gustav Mahler – Briefe, Wien: Zsolnay, 1982. 164f ). “I see it more and more: one does not compose, one gets composed.” (Bauer-Lechner, Natalie. Souvenirs de Gustav Mahler: Mahleriana, Paris: L‘Harmattan, 1998. 227).

[15] Paul Klee, “Der Begriff ohne Gegensatz nicht denkbar – Die Dualität als Einheit behandelt” in: idem, Das bildnerische Denken (Basel: Schwabe 31971) 15-17, here 17.

[16] In Klee's words: “It is all about taking a position primordial to creation” (Klee, “Redigierte Tagebuchnotizen für Otto Zoff,” loc. cit., 518). “[…] where the power-house of all time and space – call it the brain or heart of creation – activates every function; who is the artist who would not dwell there? In the womb of nature, at the source of creation.” (Paul Klee, “More here than there, Ghosts of genius,” in: The Inner Eye – Art Beyond the Visible. ed. Marina Warner. London: South Bank Centre, 1997. 48). Cp. also, “I live […] somewhat closer to the heart of creation than usual. But not nearly close enough.” (Marcel Franciscono, Paul Klee : His Work and Thought, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1991. 5).

[17] For the first the works of the artist group “Zero” or of Mario Merz could be taken as examples, for the latter the aleatoric approach in music or that of Jackson Pollock in painting.

[18] Emil Nolde, Jahre der Kämpfe (Berlin 1934), cit. in: Walter Hess, Dokumente zum Verständnis der modernen Malerei (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1956) 45. Cp. also: “So eagerly I want my work to grow out of the material.” (Emil Nolde, Briefe aus den Jahren 1894-1926, ed. M. Sauerlandt: Berlin, 1927. in: Walter Hess, Dokumente zum Verständnis der modernen Malerei, Reinbek/Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1956. 45).

[19] Conversations with Cézanne, loc. cit., 111.

[20] Cp. Morton Feldman: “Before, my pieces were like objects; now, they're like evolving things” (cit. in: Morton Feldman: List of Works – Werkverzeichnis. London: Universal Edition, 1998. 3).

[21] Alberti was of the opinion that nature from time to time brings about pictorial images – according to him this was the origin of art. Thus nature often paints “in the breakages of marble […] centaurs and faces of bearded and curly headed kings.” (Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, [First appeared 1435-36] trans. John R. Spencer. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970. 19) Alberti goes on stating that, “It is said, moreover, that in a gem from Pyrrhus all nine Muses, each with her symbol, are found clearly painted by nature.” Nature already produces works of art and the anthropogenic production of art then builds on the artificial entities produced by nature. – The idea that art originally is an evolutionary product of nature and that the intentional production of art can be traced to the non-intentional workings of nature continued to have an effect on concepts in cultural theory that advocated a reconciliation of art and culture on the one hand and nature on the other. Schelling, for example, saw the task of the artist in the attempt to follow the “the spirit of nature […] working in the core of things” while creating artistic works and thereby “return to nature.” (Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, The philosophy of art, an oration on the relation between the plastic arts and nature, trans. A. Johnson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1845. 9-10). Accordingly, Caspar David Friedrich understood his artistry as a depiction of the deeper essence of nature. (vgl. Caspar David Friedrich in Briefen und Bekenntnissen, ed. Sigrid Hinz. Berlin: Henschel, 1968. 95 a. 92). Schlegel's aphorism that “man is a creative retrospection of nature upon itself” resumes this notion in its shortest form. (Friedrich Schlegel, “Ideen,” [written 1799, published 1800] in: idem, Kritische Ausgabe, ed. Ernst Behler. Vol. 2. München: Schöningh, 1967. 256-272, here 258 [Nr. 28]). Even Kant upraised the perfect impression of naturalness as a criterion of artistic success: the finality in the form of the artifact has “to appear so free of the restraints of arbitrary standards as if it were a product of nature itself.” (Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, trans. J.H. Bernard. London: Macmillan, 1914. Div. I §45 187) Of course one has to be able to “realize that it is art and not nature” while beholding “a product of beautiful art” (idem. Div. I §45 188). Yet, beautiful art “must look like nature, although we are conscious of it as art” (idem. Div. I §45 188). In his writings on the philosophy of history, Kant thought even further and declared that the perfected state of culture will again take a natural form since it is the “ultimate goal of the moral vocation of the human species“ that “perfect art becomes nature again” (Immanuel Kant, “Conjectural Beginning of human history,” trans. Allen W. Wood. Anthropology, History, Education, ed. Günter Zöller, Robert B. Louden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. 171).

[22] The frottages of Max Ernst are paradigm examples for this. The surface texture of objects is reflected in the work by means of the frottage technique. In this respect the objects themselves are participating in their depiction – it is as if they themselves produced their own image. Cp. Wolfgang Welsch, “Frottage“ – Philosophische Untersuchungen zu Geschichte, phänomenaler Verfassung und Sinn eines anschaulichen Typus (Bamberg 1974).

[23] Cp. Cézanne, “An artist is only a receptacle for sensations, a brain, a recording device” (Conversations with Cézanne, loc. cit., 111).

[24] Cp. Wolfgang Welsch, “Kreativität durch Zufall – Das große Vorbild der Evolution und einige künstlerische Parallelen,” in: Kreativität – XX. Deutscher Kongress für Philosophie, Kolloquienbeiträge (Hamburg: Meiner, 2006) 1185-1210.

[25] This is similar to what Roland Barthes diagnosed with regard to literature. Since the invention of literature, all forms it can possibly take have been played through. Contemporary literature is now concerned with the deconstruction of its own history, the reaching of a point zero and an adequate neutral mode of writing that Barthes calls “the zero degree of writing” (Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 5).

[26] In this respect, the program of the last Biennale di Venezia (2009) was almost atavistic. Its motto was Fare Mondi – Making Worlds. The director Daniel Birnbaum declared, “a work of art […] if taken seriously must be seen as a way of making a world.” This was a retrograde conjuration of the old pathos, the antiquated ideology of creation.

[27] Allusion to the title of a book by Lucius Burckhardt: Design is invisible (Lucius Burckhardt, Design ist unsichtbar. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 1995). Already for Joseph Beuys it was a “characteristic of great art that it just doesn't force itself on you at all, but rather completely merges with its context, almost vanishes in nature” (Joseph Beuys, in: Volker Harlan, What Is Art? Conversations with Joseph Beuys. East Sussex: Clairview Books, 2004. 37).