The Platonic Mimesis and the Chinese Moxie

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 2 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

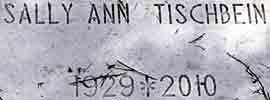

Sally Ann Tischbein (1929-2010) |

Sally Ann Tischbein (1929-2010) |

The Platonic Mimesis and the Chinese Moxie

Wang Keping

The Platonic Mimesis and the Chinese Moxie*

The Platonic notion of mimesis is applied to painting above all, and so is the Chinese notion of moxie. Both of them are used at large to indicate the technique of imitative or representational art of certain kinds. They seem to be somewhat similar in appearance such that they are often treated as universals regarding art making under certain circumstances in modern Chinese aesthetics and art criticism. As a matter of fact, they are distinct from one another in principle due to their deep implications and philosophical ponderings each. According to Plato, mimesis produces phenomenal shadows or imperfect replicas, and its products are derived not merely from man-made artifacts, but also from natural objects. Reflected and revealed through the couch allegory in The Republic, it involves both a value judgment and a hierarchical structure of reality, structure that is composed of three levels, including the first reality in the ideal Forms, the secondary reality in the natural objects and artifacts as well, and the third reality in the visual images. With respect to the Chinese conception of moxie (copying and drawing), it denotes at least two kinds of interrelated practice: linmo and xiezhao. Quite briefly, the former refers to the studio learning of practical skills by making replicas of the well-recognized paintings of preceding masters, while the latter to the outdoor study of live objects or the vis-à-vis drawing of natural scenes. When developed further, they conduce to the final stage of chuanshen that means to express the vital power and spirit of what is known in Chinese as tiandi (Heaven and Earth). The three stages constitute a progressive process of cultivation, corresponding to a threefold development of perception and experience in the realm of painting. This discussion attempts to look into these two notions and their respective implications relating to art making in two different contexts of theoretical and practical hypotheses.

Mimesis and the Hierarchical Structure of Reality

The Platonic doctrine of mimesis is threading through the history of Western aesthetics and art criticism as well. The Greek ‘mimesis’ is usually translated into ‘imitation’ in some modern European languages. When the translation is taken as an equivalent to the source term, it could be misleading to the extent that mimesis means nothing more than copying an object through the craft of imitation. In order to retain the distinction, some philosophers attempt to render mimesis into, for instance, ‘representational action,’[1] ‘representation-cum-expression’[2] or ‘make-believe’[3] with reference to its usage in the domain of artistic creation. When looking into these varied renderings along with etymological investigations, we still find something missing without a due consideration of Plato’s theory of mimesis in the light of his philosophical preoccupation with reality per se.

Then what is mimesis according to Plato? As is allegorically stated in the Book Ten of The Republic, mimesis is the action taken by the painter, ‘the producer of the product three removes from nature.’[4] For he is unable to contribute anything to the creation of the ideal Form of the couch, and therefore chooses to take a mirror and carries it about everywhere, speedily producing the appearance (phainomenon) or phantasm (phantasmatos) of the things around, but not the reality or the truth (aletheias) of them at all. In a word, the painter himself is an imitator (mimetes) of appearance or image-maker. His painting is an imitation of a phantasm. The mimetic art in which he engages only touches upon a small part of the object(s) concerned. Accordingly, the theos or god is respected as the natural begetter of the couch eidos or Form in itself, and he creates the real couch in nature of a unique kind.

The carpenter is conceived as the maker of a couch, and he makes the wooden couch on the model of the Form in itself by means of close and direct contemplation. The painter is then seen as an ‘imitator’ of the wooden couch, and he draws out what the couch appears to be in his eyes.

From the couch analogy in question, we perceive ‘a hierarchical structure of reality’ as W. J. Verdentus claims.[5] Within this structure, there arise three levels of reality, including the ideal Forms, visible objects, and images, each of which is trying to express the values that grow increasingly superior when viewed from a bottom-up angle. As a rule, the degree of reality is determined by its degree of approximation to perfect reality or god-made eidos. The empirical world does not represent true reality, but only an approximation to it, say, it demonstrates ‘something that resembles real being but is not that,’[6] or ‘yearns’ to be like the ideal Forms but ‘falls short’ of them;[7] thus ‘with difficulty’ it reveals something of the superior world of which it provides certain images or eikonas.[8] Yet, it is through the images that one will be able to behold the nature of what is hidden in the imitation, or ‘see beauty shining in brightness.’[9] This is possible on the condition that the beholder is bestowed with a powerful vision or god-like capacity for reality in images.

The structure aforementioned can be also perceived in a top-down manner. In so doing, one discerns a gradually fading sheen of eternal radiance that is prevailing through all stages of reality. This is vividly illustrated by the couch allegory in which the ideal Form descends into the visible object, and then the visible object into the image. Since it is always the case that the sharpest vision sees things first for their eye-catching appearance, the images will stand out as a helping guide, setting the vision into the channel and leading the viewer to gain an insight into reality. Accordingly, the image, especially the artistic image, should not be confined to the limits of its visual model. Likewise, art, and especially true art, should not lapse into flat realism, but strive to transcend the material world. By virtue of its images it works to evocate something of that higher realm of being which glimmers through phenomenal reality. For Plato the function of evocation and likeness derived from images in true art does not refer to commonplace reality, but to ideal Beauty.

When this happens, the term ‘image’ turns out to be rather crucial due to its significant role in the up-lifting experience of the cognitive progression and the artistic transcendence of the material world. Image itself indicates a close connection between Plato’s doctrine of mimesis and his hierarchical conception of reality. As is noted in a number of Plato’s dialogues, the notion of mimesis is at the core of his philosophical speculation, and often applied to other different domains rather than art itself. For instance, linguistically, words are mimeseis of things in letters and syllables in order to name and grasp the being or essence of each of what they signify;[10] harmonically, sounds are the mimeseis of divine harmony in mortal movement such that they afford the delight to the wise instead of pleasure to the foolish;[11] epistemologically, human thoughts and arguments about the nature of the universe as the supreme good are mimeseis of reality in terms of the completely unstraying revolutions of the god;[12] cosmologically, time imitates eternity and circles according to number with the help of the divine Father;[13] politically, laws are the imitations of the truth of each and every thing issuing from those who really possess the expert knowledge of statesmanship,[14] and human government or constitution is expected to imitate a correct and appropriate one for the better rather than for the worse;[15] religiously and spiritually, devout men try to imitate their gods and emulate them in every way they can; if they happen to draw their inspiration from Zeus, they would pour it into the soul of the one they love and help him take on as much of their own god’s qualities as possible;[16] visible figures attempt to imitate eternal ones after their likeness in a marvelous way that is hard to describe;[17] and ordinary beings would make every effort to imitate the life of those who are said to have led under god, and they do so in order to secure their happiness.[18] So on and so forth.

All this suffices to prove that the Platonic mimesis ‘is bound up with the idea of approximation and does not mean a true copy.’[19] The matter of fact is that Plato himself has warned us against any mechanical identification of the image with all the qualities of that which it imitates. For an image is to be an image after all. It may be far from possessing the same qualities as the original concerned. That is to say, imitation or mimesis ‘can never be more than suggestion or evocation.’[20]

To sum up, if we accepted the observation on the hierarchical structure of reality, we could logically claim that the ideal Forms stand for the first reality, the visible objects the secondary reality, and the images the third reality. The first reality is the original cause, while the secondary and the third reality are derivatives. At this point we could figure out certain aspects of what Plato’s doctrine of mimesis actually means to us. Here ‘by imitating the visible objects’ is, for example, meant to make images that bear their likeness or resemblance. Such likeness is appealing to our perception and vision because of its beautiful appearance or aesthetic merits. It offers a double-fold service in actuality. On the one hand, it stirs up the curiosity of the beholder and then encourages him to search through appearance for reality itself. This is positive in a sense that its cognitive worth is hidden in its aesthetic value. It can be therefore depicted in terms that the outward image will lead to the discovery of the inward truth via due contemplation. On the other hand, it is ‘vague and deceptive’ to the extent that ‘since we have no precise knowledge of such things, we do not examine these paintings too closely or find fault with them, but we are content to accept an art of suggestion and illusion for such things.’[21] Obviously this is negative as it keeps us aloof from reality or in sheer deception, but we seem to enjoy being obsessed in such a playful kind of art of suggestion and illusion.

Since artistic mimesis produces images that either expose or compose the third reality, it is by nature associated with the secondary and the first reality alike. This association is manifested to varied degrees of approximation to the visible objects first, and to the ideal Forms next. Such an artistic mimesis can be regarded as a form of symbolic evocation to lay bare the underlying relationship between the mimetic image, the useful artifact and the original eidos[22]. In other words, although it consists in the third reality or common sensuous experience, it is symbolically evocating not only the secondary but also the first reality. As we can come to know the arrival of autumn by looking at a fallen leaf, we are well in the position to realize the first and secondary reality by contemplating the images as the outcome of artistic mimesis. For these three levels of reality are leagued with one another even though they are hierarchical in value judgment.

Moreover, artistic mimesis at its best does show its metaphysical tincture despite that it has no match for Plato’s expectation of philosophy as ‘the true Muse’ or “alethines Mouses”.[23] This tincture is symbolic not merely of the first reality as the original cause of all other types of reality, but also of the divinity in more concrete images, say, in iconographic paintings and sculptures in the Hellenic art. When Plato prescribes what a painter as an imitator does with a mirror carried about everywhere while making images of everything around, it can be logically inferred that the painter is able to imitate as he pleases whatever he encounters and thinks worth imitating. He is by no means confined to the couch only, but remains free to draw and contrive many other things including the images of gods and goddesses as are exemplified in the Greek vases, not to speak of those depicted in the Homeric epics. He owes what he does to his thinking and imagination. His thinking comes from the power of reason, a divine element inane in humankind according to Plato. It is acclaimed to enable human as human to become god-like to some extent. Meanwhile, his imagination could be creative and help him produce numerous objects or icons of varied kinds including those of religious worship and spiritual enhancement. In this case, the resulting effect of revelation and morality might be trivial and less proportionate to true philosophers, but tremendous and even indispensible to common folks. This is convincing and self-evident in temple or church art across the world from the past to the present.

Moxie and the Progressive Process of Cultivation

When the Platonic notion of mimesis was introduced into China in the early 20th century, it was rendered into mofang meaning to copy or reproduce a given object only. The Chinese rendering is found not merely misleading because it scratches at the surface meaning of mimesis regardless of Plato’s aesthetic consideration of beauty and philosophical preoccupation with reality. It is also mistaken for a universal principle of art making as it appears coincidently overlapping in meaning the Chinese notion of moxie in a way.

As is noted in the tradition of Chinese painting, the concept of moxie as such would be used earlier for linmo proper. With the passage of time its meaning has got enriched and expanded to the extent that it can be employed to denote two stages of interrelated practice: linmo and xiezhao, both of them can be understood as artistic imitation but with distinct objects and orientations. Quite briefly, linmo refers to imitating or copying the works of well-known painters. It is very close to the principle that emphasizes the importance of learning from the old masters. By repeatedly imitating the works of the old masters, the immature painter, just like an apprentice, was to acquire basic skills in the artistic use of brush, ink, strokes, lines, colors, shades, blanks, compositions and the like. Meanwhile, he was to observe and apprehend the artistic styles and significant forms from which he may discover some fundamental frames of reference for his future development in painting. Moreover, he would come to see painting as a comprehensive art because its representation and expression are an organic combination of poetry, calligraphy, and seal cutting apart from drawing itself. All this suggests that a successful painter need to have a sound command of fours types of expertise, say, he is expected to be a good painter, poet, calligrapher, and seal-cutter altogether. For this reason, an experienced viewer of a traditional Chinese painting tends to make his aesthetic judgment according to the maturity and uniqueness of the four skills as a whole in expression. In order to get into this level of expertise, a gifted and ambitious painter will practice constantly to produce linmohua as duplicated paintings that help develop and demonstrate his artistry in the four inter-connected skills.

As regards the exercise of xiezhao to follow up, it is more or less like xiesheng and xiezhen, engaging the maturing painter to portray directly on the model of the natural objects including all types of landscapes and beings. In a more technical sense, it performs a necessary way of learning from Nature. Conventionally, a Chinese painter is liable to treat Nature as his teacher or a mysterious creator who transforms things and scenes into beautiful forms, grotesque images, and even ‘artistic works’ beyond human capacity. In brief, if the practice of linmo stands for the elementary stage during which the immature painter stays indoors and copies the masterpieces in the studio mainly for skill training, the practice of xiezhao implies a higher stage during which the maturing painter steps into the open air and produces images of natural objects. On this latter occasion he is supposed to be artistically keen and observant, able to find out the delicate features of the physical objects, feel the living ambiance of natural surroundings, and express them as freely and adequately as possible. At this stage he endeavors to produce muhua as eye-perceived paintings that exemplify his artistic sense of maturity and aesthetic taste of individuality.

However, linmo and xiezhao are not enough, because neither of them is highly recommended by the first-notch artists and critics in one sense,[24] and in the other sense, neither of them could compose the best paintings at all. The best paintings could be created only by virtue of chuanshen, meaning to express the inner spirit and unique quality (jingshen tezhi) of the objects as symbolic parts of the cosmos. In order to nourish the genius of chuanshen, the artist ought to learn how to express the vital and rhythmic flow (qiyun) of Heaven and Earth. Here the phrase ‘Heaven and Earth’ is metaphorically used for the universe, cosmos or all things under the sky. An artist who wants to fulfill this ultimate goal of artistic creation needs to nurture and enhance such virtues as supreme sensibility, transcendent wisdom, creative imagination, pure taste and spiritual freedom, among others. He will possibly come to roam freely around in the endless space and time while enjoying the great Beauty of silence between Heaven and Earth. Eventually, with the help of his life-long cultivation of the virtues aforementioned, he will move onto the third stage. By then he will be able to produce xinhua as mind-inspired paintings that express his spiritual enlightenment and freedom and even his ideal of life. One of the typical samples could be the landscape of The Solitary Fisherman on the Hanjiang River (Huanjiang dudiao tu) by Ma Yuan in the 13th century. Such paintings are not merely mental schemes stemmed from imagination. They are in fact organic incorporation of idealized visions with unique features embodied in the sensuous appearances of natural scenes. They probably involve such virtues as sharp observation, affinity to Nature, creative imagination, appropriate abstraction and artistic inspiration above all. All this enables one to identify himself with the beautiful in Nature as he manages to go beyond from the state of finite being into the state of infinite being.

Quite notably, what is described above comprises the three stages of traditional Chinese painting. The first stage is devoted to learning from the preceding masters that will concentrate on imitating the masterpieces and then produce the super replicas at its best (linmohua).

The subsequent stage is dedicated to learning from Nature that will focus on drawing directly the natural landscapes and living beings, and then produce eye-perceived paintings (muhua). The third stage is applied to learning from the spirit of Heaven and Earth that will encourage the free expression of the vital and rhythmic flow of the universe and create mind-inspired paintings (xinhua) as a consequence. Apparently the three stages imply a ladder of artistic development and personal cultivation as well. They are also hierarchical in terms of both skill improvement and value judgment. During this process in question, a painter goes up step by step to upgrade his artistry, and consequently his work gets closer and closer to free creation without any mechanical obstacles or confinement.

This line of thought runs through the history of Chinese painting. It can be traced back to Xie He and Zhang Zao who have discovered the hidden link between the three stages concerned.[25] However, it is explicitly stated by Dong Qichang (1555-1636) in this argument:

A painter firstly learns from the old masters, and then from natural landscapes…he learns from the old maters perfectly to the extent that he goes further to learn from Heaven and Earth. If he gets up every morning to contemplate the changing clouds over and flowing mist amid the mountains, he will find something far better than the painted scenes. When encountering a grotesque tree in the mountains, he must look at it from the four directions…Only when he gets so familiar with it, he can naturally express its spirit rather than its image. He who expresses its spirit is bound to do it in form. As the form and the mind are cooperating so freely as to make the painter forget the distinction between them, the spirit of the object painted can be best expressed.[26]

Subsequently Dong generalizes his view of painting into three basic rules as follows:

A painter learns eventually from Heaven and Earth (yi tiandi wei shi), intermediately from natural landscapes (yi shanchuan wei shi), and initially from old masters (yi guren wei shi).[27]

Dong made this argument at the age of 51 after a long and painful exploration in his artistic experience and creation. His distinction between the three stages is a subtle and delicate one. According to Zhang Yuhu, to learn from Heaven and Earth (yi tiandi wei shi) is also termed in Chinese as shi tiandi. It is a kind of free and creative activity, aiming to embody “the infinite” (wu xian), and corresponding to the demand that the painter “use an ink brush to express the spirit of the cosmos as the Supreme Void”.[28] Then, to learn from natural landscapes (yi shanchuan wei shi) is also known in Chinese as shi shanchuan or shi zaohua, it is still confined to the appearance of things even though it provides the origin of the painted landscapes on paper. It is physically “specific and finite” (queding er youxian) by nature, in spite of the fact that it is a bit more advanced than learning from old masters (yi shanchuan wei shi) identified in Chinese with shi guren.[29]

Incidentally, the similar ideal is embraced by Shi Tao (1642-1718) who proclaims poetically that “My ink brush draws freely without hesitation. The older I grow, the more I get engrossed in learning from Heaven and Earth.”[30] Later on, it is stressed and justified by Huang Binhong (1865-1955) who asserts that ‘Nature comes into painting, and painting overtakes nature…Nature has its spirit and rhythmic force that contain beauty inside. Common people cannot see it, but the painter can detect and express it to its full extent…A true landscape painting is an expression of both the essence of nature and the state of mind.’[31] All this is intended to verify the principle of learning from Heaven and Earth, and to give more credit to its outcome of xinhua as mind-inspired paintings owing to their aesthetic, philosophical and spiritual values, even though it is no easy task to create such kind of works. I personally share some of their observations in this regard. Furthermore, as it seems to me, what corresponds to the three stages is not only a progressive process of cultivation, but also a hierarchical scale of perception. The scale can be also categorized into three levels as such: The first level is oriented towards the acquisition of skills and crafts. It helps the artist foster his basic knowledge and understanding of painting as a genre of visual art. As he is exposed to the expertise of poetry, calligraphy, seal cutting and drawing as are manifested in the masterpieces that he repeatedly imitate, he will likely take them as models, and consciously practice and improve his artistic skills, literary talents, and even cultural literacy in all domains. All this is fundamental and necessary for certain. Otherwise, he will become an artisan rather than an artist in the pure sense of this term. The second level is directed to observing natural things and their life-images. Although it still lies in the exercise of artistic skills and the experience of artistic compositions, it serves to develop painter’s aesthetic sensibility, and upgrade his artistic techniques. He himself will then become more independent than dependent upon the old masters. He will be apt to abstain from their beaten track, break through the shadowy impact of the masterpieces, and strive to produce something according to his own experience, feeling and observation. Finally the third level is concerned with the nourishment of spiritual freedom and the development of independent personality. It features an exalted transformation from ‘the little self’ (xiao wo) to ‘the big self’ (da wo), during the process of which the artist identifies himself with the object, and even undergoes the peak experience of feeling the oneness between Heaven and human. Wen Yuke (1018-1079), for example, is said to feel himself into the bamboo as if he were lost in it when painting it. He therefore created in his works of bamboo natural, unique and formally significant. His experience is recorded and recommended by his contemporary Su Shi (1037-1101).[32]

It is noteworthy in traditional Chinese painting that the value of likeness is often played down in proportion because of its league with formal beauty. In the value judgment of artworks in general, formal beauty is ranked by Chinese artists and critics to be lower than vital and rhythmic beauty. According to Su Shi again, those who tend to look at a painting in light of its formal likeness are holders with a childish viewpoint. When Zhao Chang painted a flower, he applied a single dot of red instead of many, but his work was sufficiently expressive of all the charm of spring season even though it violated the conventional form of what a flower appeared to be.[33] However, the artistic presentation of likeness is not totally denied because it is indispensible so long as it is carried out to an appropriate degree. It is therefore argued that the excess of likeness is conducive to vulgarity, whereas the lack of likeness to deception. A true painting should remain between these two extremes.[34]

In addition, the painters who can create xinhua as mind-inspired paintings are relatively rare. They may come from those who will insist in life-long cultivation and pursuit. They are conjectured to owe such qualities as independent personality, spiritual freedom, contemplative concentration, rich imagination and so forth. Here are two typical examples. One is given by Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu), an early Daoist thinker. It reads as such,

When Duke Yuan of Song wanted to have a picture painted, all the court painters gathered in his presence. After they received the instructions and bowed to the duke, some of them stood around, licking their b rushes and mixing their ink. Half of them were waiting outside. One of them, who arrived late, came in leisurely steps. After he received the instructions and bowed to the duke, he did not wait but went straight to his quarters. When the duke sent someone to see what he was doing there, the painter was found undressed and seated on the mat. Duke Yuan said, ‘He will do. He is a true artist.’[35]

The other example is provided by Zhang Yanyuan (815-875) in his book on paintings. It is depicted like this:

Gu Junzhi built a high tower for his studio. Each time he climbed up onto it with the help of a ladder. When he was up there, he pulled it up into the tower such that his family members could not interrupt him any more. He did not paint until he found fine weather and beautiful scene. He never touched his brush if it remains cloudy and depressing…Hence, true painters in the history were those men of free spirit and noble sense. They demonstrated their artistic genius for a short period of time, but their great influence extended over hundreds of years.[36]

Noticeably the first story tells about a true painter or a pure artist. He ignored all the nagging formalities and social conventions. Thus he went straight to his workshop where he was found naked and seated on the mat as though he was lost in his meditation or sitting in self-forgetfulness (zuo wang). All this symbolically shows that he had detached himself from any bounds and obstacles that could be either conventional or institutional, only to return to his natural state of being. He had therefore become a free self instead of a pretentious self. The ink brush in his hand could be able to move spontaneously and draw out the imagined images that occurred to his mind (de xin ying shou). Then what he produced was but a piece of xinhua as a mind-inspired painting that was a unique creation of originality.

As for the second tale, it is intended to convince us that the painter was keen on contemplative concentration and genuine tranquility, and hence he managed to get rid of any daily disturbance and even family contact. Up there in the high tower that metaphorically implies his affinity to Nature, he was alone interacting with the spirit of Heaven and Earth and eventually feeling himself into it. Accordingly, he found inspiration and got into ecstasy when his state of mind corresponded to the pleasant weather and fascinating scene. Under such ideal conditions in accord with the union between Heaven and himself, he created his best paintings that revealed the great but silent Beauty in the universe.

Some Observations in Contrast

The foregoing discussion of mimesis and moxie in their respective contexts may shed some light on their so-called similarities as well as their essential differences. In order to further clarify these two culturally specific notions, a comparative treatment needs to be conducted hereby.

As is discerned in his discourse, Plato uses the term mimesis to restrict mimetic art to the imitation or representation of commonplace reality. His critique of mimesis as the fundamental rule of representational art aims at painting in appearance, but it is intended to attack poetry in practice. For the self-evident mimetic feature of painting can be easily utilized to convince a person of the similar character of poetry per se. Plato does this deliberately to knock down the role of poetry because it produces no knowledge of truth but only phenomenal phantasms.[37] However, to poetry he holds an ambivalent attitude if not a love-and-hate one: that is, he is aware of its magic spell such that he takes it as an emotional threat to his intellectual preference. Yet, his aesthetic interest in poetry prevents him from abolishing it completely, and he therefore attempts to retain it in a healthy form within a containable or controllable scope. It is under such circumstances that he strives to invent philosophical poetry in the form of his dialogue to supersede mimetic poetry mainly embodied in the epics by Homer and others.

Even though the Platonic idea of mimesis with reference to mimetic art is brought forth a priori in a negative sense, it inspires a wealth of imaginative rethinking due to its varied implications. First and foremost, it suggests a hierarchical structure of reality as is exposed previously. It underlies the Platonic intellectualism, and encourages epistemological probe into the ideal Form in itself. It is intentionally pointed to the recognition of the god as the creator of all, and to the understanding of the one-cum-many cluster of Forms at different levels. All this poses a continuous process that leads one to hanker after a philosophical way of life, a way of life that will lead human as human to untiringly nourish wisdom and excellence, and eventually to become ‘god-like’ as Plato advises.[38]

Secondly, the doctrine of mimesis as such reveals the ontological status of art in general. This is due to the procedure of image-making in which the painter initially paints a couch according to the wooden model shaped by carpenter. This painted couch represents a visual image and formal beauty of an artifact. It is based on mimetic craft and sensuous perception that is metaphorically likened to mirror-like function or representation. All this exemplifies how art—particularly mimetic or representational art—comes into being in principle, and becomes what it looks like in form. It is in this sense that the Platonic mimesis is considered to be “in substance an important foundation-stone of aesthetic theory” in the West, notwithstanding that Plato himself remains “profoundly hostile to the value of the poetic world”.[39]

Thirdly, Plato’s metaphysical estimate of mimetic art bears a hidden link with his psychological estimate of artistic symbolism, symbolism that stands for the embodiment of invisible realties or Platonic Ideas in sensuous form. This means that either from a bottom-up or top-down perspective, the first reality, the second reality and the third reality can be conceived as analogously associated with and symbolic of one another within their hierarchical structure. In plain words, if the painted couch is a direct mimetic shadow of the wooden couch, it is difficult not to deny its being an indirect mimetic shadow of the couch eidos as the ideal Form. Moreover, a mature painter could hardly stick to the logical sequence as Plato has set up. He would be ready to venture beyond the boundary of artifacts, and to represent the shapes of his surroundings and many other natural objects in esse on the one hand, and on the other, he may extend his power of imagination to portray the abstract ideas, spiritual entities and invisible deities by turning them into sensuous images. This is in fact evidenced in the survived Greek art works in the forms of vases and sculptures.

Last but not the least, the translation of mimesis into either “imitation” or “representation” seems to be misleading in a way. For the Greek word itself carries a gradation of meanings that ranges from imitation, representation, reproduction, make-belief, image-making, to art creation. In addition, it signifies a kind of symbolic imagination and representation-cum-expression with regard to the representation of the invisible in the sensuous images, and the expression of the abstract and the spiritual in the perceptible forms by virtue of the magic power of imagination and mimetic technique. As for its ultimate telos, it lies not merely in the appreciation of aesthetic and moral values, but also in the consideration of epistemological and cosmological ones, with respect to the constant pursuit of the possible cognation of the highest Idea of Good as the first cause of all things in the universe. All this poses an inexhaustible enterprise as a result of its infinite space for thinking and imagining.

When it comes to the Chinese notion of moxie, it is divided into two interrelated stages of artistic practice: one is linmo meaning to imitate the works of the old masters so as to develop painting skills, and the other is xiezhao meaning to portray natural landscapes so as to improve artistic expertise. Both of them involve no metaphysical estimate but practical estimate. They seem to be largely skill-oriented even though one is elementary and the other is advanced to some degree. However, this value judgment does lead to any negative attitude towards either linmo or xiezhao, because they are recommended as desirable and interrelated steps of improving the painting repertoire and aesthetic sensibility of the artist himself. According to Chinese tradition, linmo is assumed to foster mainly reproductive skill whereas xiezhao to enhance visual sensibility. The former enables one to produce replicas of established works, while the latter to create resemblances of natural objects. The chief discrepancy between them could be that between the rigid duplication of masterpieces and the relative flexibility of transfiguring natural landscapes. Consequently, there arises the distinction between linmohua as reduplicated paintings and muhua as eye-perceived paintings. Correspondingly, reduplicated paintings are the outcome of learning from old masters (shi guren), and eye-perceived paintings are the fruit of learning from natural landscapes (shi shanchuan).

Nevertheless, these two types of painting are not the ultimate pursuit after all. Similarly, these two stages of practice are not the final destination either. Both of them are actually employed as a springboard for the artist to jump higher ahead. In other words, moxie as a synthesis of linmo and xiezhao can be more significant when it is connected with the final stage of chuanshen meaning to express the inner spirit and vital rhythm of all things in the universe. This final stage enables one to create xinhua as mind-inspired paintings by learning from Heaven and Earth. As is described earlier, the three stages come to comprise a progressive process of cultivation along with a hierarchical scale of perception. All this commends a moral cultivation of personality, and expects one to develop a high awareness of the Dao as the most accommodating spirit of Heaven and Earth in one sense, and as the most subtle symbol of spiritual freedom and independent personality in the other sense. In principle it is directed to the enlightened experience of the Dao in itself, and the sublimated awareness of the entire cosmos. Thus it is conducive to a continuous impetus that encourages one to move towards a Doaist way of life, a way of life that will lead human as human to become harmonious with Heaven and Earth.

Noticeably in the ultimate phase, the artist of an ideal kind is supremely imaginative, sensitive and creative. He is therefore capable of transforming mental pictures into sensuous forms by means of intuiting and experiencing. He does so in order to express the rhythmic flow and vital power of the myriad things. During this process he is feeling freely and interacting harmoniously with the spirit of Heaven and Earth (yu tiandi jingshen xiang wanglai) in Zhuangzi’s terminology. Thus he sketches out what he feels best to himself after searching through all the wonderful landscapes under the sky. His work then can resemble either all of the landscapes or none of them he has ever seen before, simply because it is unique recreation in the pure sense of this term.

Furthermore, the cultivation-oriented hypothesis in the three stages of painting is aesthetic and empirical by nature. It attempts to actualize spiritual freedom and independent personality through constant cultivation in artistic perception and creation alike. In this regard, chuanshen seems to suggest the highest form of achievement of which the first-caliber Chinese painter is capable. All this is underlined by the Chinese thought of heaven-and-human oneness, a thought that integrates both this-worldliness and other-worldliness into living experience.

Incidentally, shi tiandi as learning to express the inner spirit and vital rhythm of Heaven and Earth is characterized with a boundless pursuit due to its ever-expanding realm of intuiting and experiencing in terms of .aesthetic autonomy. Even though it appears to be somewhat mystical and unapproachable, it is intelligible to most of the Chinese artists who are more familiar with the monistic view of one world. To their minds, this one world is an organic whole consists in two parts at least: the accessible and the felt. The former refers to all things perceptible and touchable, and the latter to the vital power and rhythmic flow experiential and participatory.

Enough is said for the time being. Now it is safer to conclude that the Chinese notion of moxie and the Platonic notion of mimesis are culturally specific rather than universal, disregarding their seemingly shared aspects in imitation or duplication at the elementary levels. They seem to resemble in appearance but remain discrepant in essence. Hence they could be justifiably approached and understood only when they are placed in their respective cultural contexts. Otherwise they might be either far-fetched or over-interpreted, I suppose.

* Wang Keping; The Platonic Mimesis and the Chinese Moxie, International Yearbook of Aesthetics, Volume 14, 2010, pp. 214-233.

Notes:

[1] G. Sörbom, Mimesis and Art (Bonniers: Svenska Bokförlaget, 1966), p. 22.

[2] S. Halliwell, The Aesthetics of Mimesis (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002), pp. 14-18.

[3] K. Walton, Mimesis as Make-believe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), pp. 11-69.

[4] Plato, The Republic (trans. Desmond Lee, London: Penguin Books, 1976), 596a-597e. 216

[5] W. J. Verdentus. Mimesis: Plato's Doctrine of Artistic Imitation and Its Meaning to Us (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1972), pp. 16-17. As far as this observation is concerned, Verdentus is feeling so indebted to R. Schaerer who emphasizes the hierarchical conception of reality in his works including La question platonicienne (Neuchâtel, 1938), La composition du Phédon, Rev. Et. Gr. 53 (1940), 1-50, Dieu, l'homme et la vie d'aprè s Platon (Neuchâtel, 1944).

[6] Plato, The Republic, 597a.

[7] Plato, Phaedo. 74d, 75a-b, in Plato, Complete Works (ed. John M. Cooper, Indianapolis et al: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997).

[8] Plato, Phaedrus, 250b, in Plato, Complete Works.

[9] Ibid, 250b.

[10] Plato, Cratylus, 423e-424b, in Plato, Complete Works.

[11] Plato, Timaeus, 80b, in Plato, Complete Works.

[12] Ibid, 47b-c.

[13] Ibid, 37c-38a.

[14] Plato, Statesman, 300c-e.

[15] Ibid, 293e, 297c.

[16] Plato, Phaedrus, 252c-d, 253b, in Plato, Complete Works.

[17] Plato, Timaeus, 50c, in Plato, Complete Works.

[18] Plato, The Laws 713e, in Plato, Complete Works.

[19] W. J. Verdentus. Mimesis: Plato's Doctrine of Artistic Imitation and Its Meaning to Us, p. 17.

[20] Ibid, Also see R. Schaerer. La question platonicienne, p. 163 n.1.

[21] Plato, Critias, 107c-d, in Plato, Complete Works.

[22] Bernard Bosanquet. A History of Aesthetic (New York: Meridian Books, 1957), pp. 45-47.

[23] Plato, The Republic, 548b, Phardo, 61a, The Laws, 698d, 817b-c.

[24] In his book on Chinese painting, Zhang Yanyuan knocks down the value of moxie as one of the six cardinal principles of painting. He argues that those who cling themselves only to moxie as imitation and representation will be confined to their self-satisfaction with formal or image resemblances while ignoring the expression of the vital rhythm, to the use of coloring on surface while losing the sketching expertise. See Zhang Yanyuan, Lidai minghua ji (Commentary on the Famous Paintings in the History), in Shen Zicheng (ed.), Lidai lunhua mingzhu huibian (Selections from the Famous Historical Writings on Chinese Painting, Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 1982), p. 36.

[25] Xie He who lived in the fifth century sums up the art of painting into six leading principle including qiyun shengdong (vital rhythm and lively vividness) and chuanyi moxie (expressive transforming and imitative drawing), among others Zhang Zao who lived in the eighth century is renowned to advocate the motto of “waishi zaohua, zhongde xinyuan” that emphasizes the apperception of the living rhythm within the artist and the appealing scenes in Nature. On the occasion of this apperception as a living experience, the internal self is harmonious and interactive with the external cosmos.

[26] Dong Qichang, Hua chan shi sui bi (Essays on the Painting of Zen), in Peking University Department of Philosophy (ed.), Zhongguo meixueshi ziliao xuanbian (Selected Sources of the History of Chinese Aesthetics, Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1981), vol.2, p. 147.

[27] Dong Qichang, Hua chan shi sui bi (Essays on the Painting of Zen), vol. 2, in the Hua yuan (The Origin of Painting). Cited from Zhang Yuhu,“Cong ‘shi shanchuan' dao ‘shi tiandi'” (Learning from Natural Landscapes versus Learning from Heaven and Earth), in Wen yi yan jiu (The Journal of Literary and Art Studies), No.4, 2008, p. 113.

[28] Wang Wei, Xu hua (Of Painting), in Shen Zicheng (ed.), Lidai lunhua mingzhu huibian (Selections from the Famous Historical Writings on Chinese Painting), p.16. It says in Chinese pinyin “yi yi guan zhi bi, ni tai xu zhi ti.”

[29] Zhang Yuhu, “Cong ‘shi shanchuan' dao ‘shi tiandi'” (Learning from Natural Landscapes versus Learning from Heaven and Earth), in Wen yi yan jiu (The Journal of Literary and Art Studies), No.4, 2008, p. 111.

[30] Shi Tao, Shi Tao shu hua quan ji (The Complete Works of Shi Tao on Calligraphy and Painting, vol. 1, Tianjin: Tianjin Renmin Meishu Chubanshe, 2002), p. 98.

[31] Huang Binhong. Huang Binhong huayu lu (Huang Binhong's Collected Notes on Painting). Also see Wang Liu et al (eds.). Yishu tezheng lun (On the Characteristics of Art, Beijing: Wenhua Yishu Chubanshe, 1984), p. 21.

[32] Su Shi. Su Dongpo ji (Collected Works of Su Dongpo), vol.16. Also see Peking University (ed.). Zhongguo meixueshi ziliao xuanbian (Selected Sources in the History of Chinese Aesthetics, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1981), vol. II, p. 39.

[33] Su Shi. Su Dongpo ji. Vol. 16. Also see Peking University (ed.). Zhongguo meixueshi ziliao xuanbian. Vol. II, p. 37.

[34] Qi Baishi. Qi Baishi huaji xu (A Preface to the Collected Paintings by Qi Baishi). Also see Wang Liu et al (eds.). Yishu tezheng lun (On the Characteristics of Art), p.20. Huang Binhong, a contemporary of Qi Baishi, shares the similar opinion with respect to formal likeness in painting. Cf. Huang Binhong. Huang Binhong huayu lu (Huang Binhong's Collected Notes on Painting). Also see Wang Liu et al (eds.). Yishu tezheng lun, p. 20.

[35] Zhuangzi. Zhuangzi (The Complete Works of Zhuangzi). Trans. Wang Rongpei. (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2003), p. 353.

[36] Zhang Yanyuan. Lidai minghua ji (Commentary on the Famous Paintings of the Existent Dynasties). Cited from Wang Liu et al (eds.). Yishu tezheng lun (On the Characteristics of Art), p. 15.

[37] Plato, The Republic, 599a.

[38] Ibid, 613a-b.

[39] Bernard Bosanquet, A History of Aesthetic (New York: Meridian Books, 1957), p. 28.