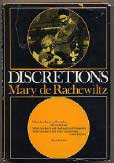

Mary de Rachewiltz - Discretions

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Ezra Pound (1885-1972) |

Ezra Pound (1885-1972) |

Mary de Rachewiltz - Discretions

Henry Regnery

A Daughter of the Poet*

Mary de Rachewiltz remarks at the beginning of her book that knowing she will probably get no comment from the author of Indiscretions that is to say from her father, Ezra Pound – takes the edge off her story. It may have taken the edge off for her, but the reader has no such impression – she has given us a beautifully written, charming book which tells us much not only about the complex author of Indiscretions, but because of her place of observation in the middle of it all, much about our time as well.

Mary de Rachewiltz

As a very young child Mary Rudge, as she was then called, was entrusted for nursing and care to a peasant family in the village of Gais in South Tyrol, the German speaking part of Austria that was transferred to Italy following World War I. This was in 1925. She grew up in the family, her first language was the local German dialect, she learned to care for the sheep, to plant, to help with the harvest, she attended the local school, took part in the strongly church-centered local customs, felt herself a part of the village. Her parents visited her from time to time, and at the age of four she was taken to Venice for her first visit to the house of her mother, the concert violinist Olga Rudge – a “house of elegance, tense symbols, charged with learning, wisdom and harmony,” as she describes it. More and longer visits followed as she grew older. She was later sent to a school in a beautiful Medicean villa above Florence conducted by nuns for girls from upper class Italian families, but Gais remained home.

Mary de Rachewiltz, Discretions, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1971.

The contrast between the two worlds in which she lived, that of a deeply–rooted peasant village and the “society of great minds in elegant surroundings” she came to know with her parents could hardly have been greater, and she brings out the differences between the two sharply and with great perception. On one occasion, for example, her mother insisted that she skip so that she might become slender and graceful; at home, in Gais, “weight was a thing to have, weight behind the work.” But both ways of life had an essential element in common-self-discipline. In the village it was the discipline of work-tending the sheep, making the hay, planting and harvesting, the pattern dictated by necessity and the seasons. There was also the discipline of custom and tradition-the scrubbing of the house from top to bottom, for example, for Easter. In the house of her parents there was the discipline demanded by achievement. Listening once to her mother practice she suddenly realized “that that’s how music should sound”; it was on quite a different level from the music of the village, its beauty “unattainable by mortals like me.” Her father saw to it that she have a good education. As part of her training, for example, he had her translate Thomas Hardy and his own Cantos into Italian. “What the world will need most when the war is over is someone with an education,” he told her. Later, but still during the early years of the war, while she was living with her mother it was arranged for her to have French and Latin lessons from an English priest who lived nearby, and during this time she was subjected to her mother’s rigidly ordered regime. At first she resented it, “But soon I came to see the logic and beauty of my new life. Strict discipline and routine left more freedom for one’s thoughts.” Life had been reduced to its essentials- there was “nothing superfluous, nothing wasted, nothing sloppy.”

Mary de Rachewiltz is of the generation which came to maturity during World War II. Born in Italy of American parents and brought up in a German-speaking area which was legally part of Italy but strongly anti-Italian, her position, to say the least, was rather anomalous, and made more so by the special position and strong feelings of her father, whom she greatly admired. In spite of all this, or, perhaps better, because of it, she seems to have kept her head. For her, the war was no clear-cut struggle between the forces of good and evil, but an immense tragedy. During the latter part of it she worked in a German military hospital; one doesn’t have the impression that it was with any idea of assisting the “war effort,” but because she had to work to support herself; that was where she was, and in the hospital her help was needed. In this, as in so much else, she showed the sound instincts and realism of the European peasant.

As for her father:

While the British and Americans systematically, so it seemed, and senselessly bombed Italy’s beautiful cities–and Sigismundo’s Temple in Rimini–Babbo, equally systematically, and senselessly perhaps, kept up his translations from Mencius and Confucius.

When the two partisans came to arrest him -to collect the reward of half a million lire they had heard had been offered for him by the Americans-he was translating Confucius, and put the book in his pocket when he was taken away. Later, an American major came twice to go through his belongings, taking some papers and his typewriter. Pound was taken to the US. Army Disciplinary Training Center near Pisa and assigned to a death cell, but this the family did not learn until six months later.

A Negro guard or fellow prisoner gave him a box to use for a desk, and he was finally allowed to use the typewriter in the headquarters building. It was there that the Pisan Cantos were written, the cantos for which he was given the Bollingen Prize for poetry. For his daughter, this award came as a gift from heaven. Her first child had just been born, and she and her husband had no idea where the money was to come from to pay the clinic when a letter arrived from her father, then confined in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, with a check for $100-her share of the Bollingen Prize.

By convincing the base censor that his poetry contained nothing seditious and no hidden personal messages, Pound was allowed to send it to his family, with instructions to make three copies. His daughter describes the impact of Canto 81:

Never had I seen Mamile [her mother] cry so unrestrainedly as when she read Canto 81:

Pull down thy vanity

And the cry of AOI is an outburst more personal than any other in the Cantos and expresses the stress of almost two years when he was pent up with two women who loved him, whom he loved, and who coldly hated each other.

Pound‘s daughter made the long trip from South Tyrol to Washington to visit him in St. Elizabeths and to do what she could to get him out. She was not successful, but she made clear to anyone who would listen how she felt about it:

He had not betrayed America. He tried to stop the war. It may be crazy to go beyond one’s duty, but he knew what he was doing. Why should he be punished because his insight and courage were greater than those of most citizens in the United States? . . . Whether one believes a poet is a seer or not, his achievements, and his long sojourn in Europe and especially Italy, did make him “qualified” to express an opinion and free speech without free radio speech is as zero. All right, it was an Italian radio, but he was broadcasting his own propaganda . . . . any person in good faith must see that certain aberrant phrases were the result of strain and exasperation. And why was he denied the privilege of habeas corpus, why was he kept incommunicado? Why?

When she asked him what she could do his answer, characteristic and unadorned, was simply, “All you can do is to plant a little decency in Brunnenburg.” When he finally was released, after almost thirteen years in an institution for the insane, she wrote:

Juridically nothing had changed except for the worse. What had changed was Babbo’s feelings. And public opinion. To this he himself had contributed the most by disregarding all yatter and clatter, tears, pleas, and threats, taking no apparent interest in his situation and not wasting thoughts on how to change it, but keeping at his job – poetry: The Odes, Trachinae, Rock-Drill and Thrones, the major accomplishments. All proofs of his sanity. And of wise man intent on fulfilling his destiny, not fighting it.

She mentions one curious and most revealing incident from her stay in Washington. On some occasion she was pleased to discover that she was speaking to Francis Biddle, the former Attorney General, pleased because he “must surely know more than anyone else,” as he should have, since it was he who issued the order for Pound’s arrest. When, however, he discovered who she was he said, with a disarming smile, “Let me get you a drink,” and disappeared. The former Attorney General of the United States encounters a woman concerned about the virtual imprisonment without trial of her father, a father, after all, who was one of the greatest poets and men of letters of his time, and can think of nothing better to say than “Let me get you a drink”- what a commentary on our time!

It is difficult, in a short review, to give an adequate idea of the wealth and breadth of the experiences this book encompasses. For me, perhaps the strongest impressions of Mary de Rachewiltz’ story are a clear, direct style-“nothing superfluous, nothing sloppy,” and serenity, the serenity of a strong-willed person who, in a chaotic time was able to establish an ordered life based on firmly held values.

* Modern Age, Fall 1972, pp. 420-422.