Mirror for Perspective

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Alma Tulli (1900-1977) |

Alma Tulli (1900-1977) |

Mirror for Perspective

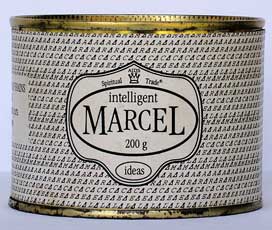

Milan Golob; Paintings and Duchamp (Intelligent Marcel / Spiritual Trade),

1994, Gallery Škuc, Ljubljana.

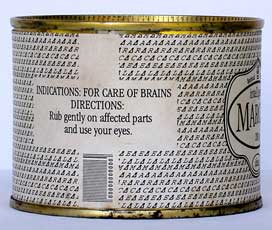

Milan Golob; Paintings and Duchamp (Intelligent Marcel / Spiritual Trade – installation view),

1994, Gallery Škuc, Ljubljana.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson

Marcel Duchamp and the New Geometries (Part 3)*

The Notes in A l'infinitif

Duchamp made his first notes for the Large Glass during his visit to Munich of July and August of 1912. The production of notes continued steadily throughout late 1912, 1913, and 1914, with the greatest number of notes written in 1913. After the artist's departure for the United States in 1915, increasingly fewer notes relating specifically to the Large Glass were made until they ceased completely in 1921 or 1922.[54]

Duchamp wrote his notes on individual scraps of paper, which are rarely dated, and for the publications, the Box of 1914, the Green Box, and A l'infinitif, the scraps of paper were reproduced in facsimile. The ordering of the notes for the translations of these boxes has thus been a major task, and no one version can be thought of as definitive.[55] Arturo Schwarz conducted the most thorough study of the notes to date in preparation for his 1969 Notes and Projects for the Large Glass, which included examples of notes from all of Duchamp's "boxes." In addition to the content of each note and the rare instances of actual dating by the artist, Schwarz gained a further criteria for his chronological arrangement of the notes by employing a handwriting analyst.

When A l'infinitif was published in 1966, an English translation of the notes in booklet form was included in each box, a text now reproduced in Salt Seller. The order of the notes for this translation was established through the joint effort of Duchamp and Cleve Gray, the translator. However, Schwarz's careful study led him to place certain notes in time periods quite different from those suggested in the A l'infinitif translation. For example, the crucial note that begins "Use transparent glass and mirror for perspective4" (Salt Seller, p. 88) is included by Schwarz as his "Note 6" among a group of eleven notes that concludes with the first layout of the Large Glass, dated 1913.[56] Thus, for Schwarz "Note 6" dates from late 1912 or early 1913. However, in the A l'infinitif translation, the note "Use transparent glass and mirror for perspective" is placed, on the basis of content, with a note written on the back of a Paris gas bill dated "Sept. 14, 1914."[57]

One possible explanation for the widely disparate dates suggested for this note is that both the note dated "Sept. 14, 1914" ("Difference between 'tactile exploration' ... ") and the following note ("Construction of a 4-dim'l eye"), on a gas bill dated "Nov. 11, 1914," may have been recopied by Duchamp from earlier notes. Duchamp did admit to Schwarz the practice of recopying notes, and at least one other such instance was discovered during the preparation of Notes and Projects for the Large Glass.[58]

Understanding the role of the new geometries in the period when Duchamp was working now provides an additional key to the mystery of the A l'infinitif notes. Examining the notes' geometrical content suggests a new logic for their arrangement, differing somewhat from that of Schwarz[59] and in a number of ways from that of the A l'infinitif text reproduced in Salt Seller. Although the artist himself participated in the decisions on grouping the notes for the English translation published in Salt Seller, the fact that these notes had been made fifty years before, as well as Duchamp's "genial remoteness"[60] on the subject, account for the variance.

Although the notes to be examined occur in three sections of A l'infinitif entitled "Appearance and Apparition," "Perspective," and "The Continuum," a different division emerges from studying the content of the notes in the last two sections.[61] All of the notes share an underlying theme of the relationship of dimensions, an idea explored most directly in "Appearance and Apparition." If this section is somewhat self, contained, however, the notes under "Perspective" and "The Continuum" do not divide as neatly as these titles suggest. On the contrary, notes from one section often connect directly with those of the other in a series of categories that may be established on the basis of the course of Duchamp's study of the problem.

Beginning with the desire to create a four, dimensional Bride, Duchamp first speculated on the problem of "four' dimensional perspective" or the more concrete ways in which a three-dimensional being might "perceive" the fourth dimension. After an initial stage, which expanded upon information gained from Princet and the Cubist discussions at Puteaux, Duchamp soon realized that an examination of both the rules of three-dimensional perspective and the laws of four-dimensional geometry would be necessary. A large group of notes chronicles his exploration of these subjects, a study that finally led him to the mirror as a symbol of the four, dimensional continuum. With the knowledge he had gained, Duchamp was able at last to achieve a complex new synthesis for representing his Bride.

"Appearance and Apparition"

The notes under "Appearance and Apparition" represent Duchamp's most basic thoughts on the relationship of the world of three dimensions to the two dimensions of art. The major note in this brief section also deals with color, but the important section on dimensions is as follows:

| Appearance | } | of a chocolate object for ex. | |

| Apparition |

1° The appearance of this object will be the sum of the usual sensory evidence enabling one to have an ordinary perception of that object (see psychology manuals)

2° Its apparition is the mold of it

i.e.

a) There is the surface apparition (for a spatial object like a chocolate object) which is like a kind of mirror image looking as if it were used for the making of this object, like a mold, but this mold of the form is not itself an object, it is the image in n-l dimensions of the essential points of this object of n dimensions. The 3-dim'l appearance comes from the 2-dim'l apparition which is the mold of it (external form).

b) As another part of the mold there is the apparition in native colors. ...

Given The object, considered in its physical appearance (color, mass, form). Define (graphically i. e. by means of pictorial conventions) the mold of the object. By mold is meant: from the point of view of form and color, the negative (photographic)j from the point of view of mass, a plane (generating the object's form by means of elementary parallelism) composed of elements of light ...[62]

With its discussion of a "chocolate object," this note is more closely connected with the Large Glass than are the more abstract notes under "Perspective" and "The Continuum." If the "chocolate object" mentioned refers to Duchamp's Chocolate Grinder, the note may date from early 1913, when Duchamp painted his first version of the Chocolate Grinder (Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection), using a strict one-point perspective system. The idea discussed in this note that the apparition or mold of an object is "a kind of mirror image" as well as "negative (photographic)" was to be essential in the artist's final resolution of the problem of representing the fourth dimension. While this note could thus be a later summation, its nontechnical nature argues that it is an early statement of Duchamp's thoughts on the basic mode of operation of figurative art.

Phase One: "Four-Dimensional Perspective"

The notes dealing with Duchamp's first attempts at establishing a "four-dimensional perspective" are to be found in both the "Perspective" and "The Continuum" sections of A l'infinitif, with two relevant notes also placed in the earlier sections entitled "Speculations" and "Further References to The Glass." The "Speculations" note shares the nontechnical quality of "Appearance and Apparition" and seems to have been an isolated thought about one possible way of going beyond three dimensions. The note simply suggests that "the optical illusions produced by the difference in [the) dimensions" of "2 'similar' objects ... (like 2 deck chairs, one large and one doll size)" might create a kind of "four-dimensional perspective," but this elementary idea cannot have satisfied Duchamp for long. The second of these notes refers to four-dimensional perspective only in its title: "Perspective4." Its real subject is "Principal forms, imperfect and freed" and the note contrasts the mensurated quality of the Bachelor Apparatus to the fluid and immeasurable nature of the Bride.[63]

As established earlier, it is likely that Duchamp learned of Jouffret's Traite elementaire de geometrie a quatre dimensions in late 1911 from his new friends in the Puteaux group. Whether he read Jouffret thoroughly in early 1912 is not known, but during the fall of 1912 after Duchamp's return from Munich, Jouffret's treatise served as a starting point for his serious notes on the fourth dimension.[64] Duchamp's reference to Jouffret, "The shadow cast by a 4-dim'l figure on our space is a 3-dim'l shadow (see Jouffret "Geom. a 4 dim." page 186, last 3 lines),"[65] was not actually a quotation from Jouffret or even a paraphrase. The last three lines of page 186 of the Jouffret treatise discuss only the two, dimensional shadow of a three, dimensional object: "To that end, consider the horizontal shadow which attaches itself to you when you walk in the sun and which, long or short, broad or slender, repeats your movements as if it understood you ..."[66] Nevertheless, while Jouffret uses this idea to introduce his description of a two, dimensional universe in the tradition of Abbott's Flatland, the analogy with the third and fourth dimensions was obvious to an early twentieth, century reader, just as it had been in Flatland.

In geometry such a three-dimensional "shadow," if made perpendicularly, is in effect a "section" of the four, dimensional figure, and the above note continues in this vein:

Three-dimensional sections of four-dimensional figures by a space: by analogy with the method by which architects depict the plan of each story of a house, a four, dimensional figure can be represented (in each one of its stories) by three-dimensional sections. These different stories will be bound to one another by the 4th dim.

Construct all the 3-dim'l states of the 4-dim'l figure the same way one determines all the planes or sides of a 3-dim'l figure-in other words: A 4-dim'l figure is perceived (?) through an 00 of 3-dim'l sides which are the sections of this 4-dim'l figure by the infinite number of spaces (in 3 dim.) which envelope this figure.-In other words: one can move around the 4-dim'l figure according to the 4 directions of the continuum. The number of positions of the perceiver is 00 but one can reduce to a finite number these different positions (as in the case of regular 3-dim'l figures) and then each perception, in these different positions, is a 3-dim'l figure. The set of these 3-dim'l perceptions of the 4-dim'l figure would be the foundation for the reconstruction of the 4-dim'l figure.[67]

This note is actually a summary of the lessons the Puteaux Cubists learned from the writings of Jouffret and Poincare. The architectural method Duchamp describes is that of the isometric or axonometric projection, a process very like the perspective cavaliere used by Jouffret in his Traite elementaire to present unified views of four, dimensional figures.[68] These were the diagrams in Jouffret which must have struck Princet as so like Cubism's juxtaposed views and which had lead Gleizes and Metzinger to codify their doctrine of the artist's movement about his object. Poincare had provided the Cubists with a perfect description of their method in the passage from La Science et l'hypothese quoted in Chapter 2.[69] Duchamp's final paragraph in this note seems based directly on Poincare's explanation and represents the artist's starting point for his further researches into Poincare's thought.

Duchamp quickly began to explore the implications of Poincare's writings on perceptual space, going beyond Gleizes's and Metzinger's brief statements based on Poincare's distinction of visual, tactile, and motor space. The notes that logically follow the note beginning with the reference to Jouffret above are those involved in the difficult problem of dating discussed earlier. In line with Schwarz's placement of the note commencing "Use transparent glass and mirror for perspective4" in late 1912, the two notes that succeed it in Salt Seller (on gas bills dated "Sept. 14, 1914," and "Nov. 11, 1914") were more likely composed in late 1912 or early 1913 and then recopied on Paris gas bills later.

The third of these three notes simply speculates on the "Construction of a 4-dim'l eye" (Salt Seller, pp. 88-89), comparing its vision of a sphere with the human eye's view of a circle. However, the complexity of the discussion in the first two notes requires their quotation in full. The first note reads as follows:

Use transparent glass and mirror for perspective

analogy: perspective: the 3-dim'l perspective representation of an object will be perceptible to the eye just as the perspective of a cathedral is perceptible to the flat eye (and not to the eye). This perception for the eye is a wandering, perception (relating to the sense of distance) - An eye will only have a tactile perception of a perspective. It must wander from one point to another and measure the distances. It will not have a view of the whole like the eye. By analogy: wandering-perception by the eye of perspective.

And in the closely related note on the back of the "Sept. 14, 1914," gas bill Duchamp

continues:

Difference between "tactile exploration" or the wandering in a plane by a 2-dim'l eye around a circle, and the vision of this very circle by the same 2-dim'l eye fixing itself at a point. Also: difference between "tactile exploration," 3-dim'l wandering by an ordinary eye around a sphere and the vision of that sphere by the same eye fixing itself at a point (linear perspective). Also: the same difference exists in the 4-dim'l domain: there is "tactile exploration" in the 4 dimensions of a 3-dim'l visual perspective perception of the 4-dim'l body. This 3-dim'l visual perspective perception is only distinguishable to the 4-dim'l eye. The 3-dim'l eye will not distinguish it clearly (just as the 2-dim'l eye only sees the projected segment of a circle). A 3-dim'l tactile exploration, a wandering around, will perhaps permit an imaginative reconstruction of the numerous 4-dim'l bodies, allowing this perspective to be understood in a 3-dim'l medium. Use transparent glass Use transparent glass.[70]

Poincare's analysis of perceptual space in La Science et l'hypothese had established for the Cubists that spaces based on tactile and motor sensations might have more than three dimensions and even that "motor space would have as many dimensions as we have muscles."[71] Poincare was likewise the source of Duchamp's interest in "tactile exploration" as the means for a two' dimensional eye to perceive a three-dimensional object or for the human eye, a three, dimensional eye, to perceive a four-dimensional object. The two-dimensional eye is incapable of perceiving the third dimension of an object without moving around that object, just as a three, dimensional eye cannot distinguish the fourth dimension of an object from a single point in a purely visual perspective. Instead, the three, dimensional eye must explore, accumulating a series of perceptions of the four, dimensional object, in the way Poincare's method for four, dimensional representation had suggested.

Duchamp's initial work on the problem of representing the fourth dimension through a kind of "four-dimensional perspective" may be described as a tactile, physical approach. In the end, Duchamp was forced to give up this more concrete method in favor of a visual illusion of the fourth dimension based on mirrors and virtual images. It is curious that one of the early, thoroughly "tactile" notes quoted above begins, "Use transparent glass and mirror for perspective," an idea Duchamp was not to develop until later.

The theme of "grasping" is prevalent in a number of other notes on "four-dimensional perspective," which appear to date from this early stage of Duchamp's investigation. One note is included in the "Perspective" section of A l'infinitif with the four notes discussed above, while the others are interspersed among the notes under "The Continuum." The important segments of three of these notes are as follows:

Perspective4 will have a cube or 3 dim'l medium as a starting point which will not cause deformation i.e. in which the object3 is seen circumhyperhypo-embraced (as if grasped with the hand and not seen with the eyes).[72]

4-dim'l Perspective

Analogies

I. In a 3-dim'l continuum

A.B.C.: 3 plane objects on plane P.

X X' X": three different points of sight

For a 3-dim'l individual, the 2-dim'l retinal image is different at each point of sight (X X' X" etc.) - (Hence linear perspective).

II. In a 4-dim'l continuum

A' B' C': 3 solid objects in 3-dim'l space S.

Define the grasp

a starting point

for this grasp,

etc.

For a 4-dim'l individual, the 3-dim'l tactile grasp-image (like a penknife in one's fist) will differ when the (point? where the grasp? starts?) moves 4-dimensionally.[73]The vision3 of a plane P. corresponds in the continuum to a grasp4 of which one

can get an idea by holding a penknife clasped in one's fist, for example.[74]

This last sentence occurs in a note that is also concerned with the laws of the four, dimensional continuum, a reminder that while pursuing his "four-dimensional perspective" Duchamp had simultaneously begun to research both traditional three-dimensional perspective and the principles of n-dimensional geometry.

Three-Dimensional Perspective

From early 1913 Duchamp's job as a librarian at the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve offered ready access to a wealth of information on perspective, as well as on geometry. The first note in the "Perspective" section of A l'infinitif documents his use of the library:

Perspective.

See Catalogue of Bibliotheque St. Genevieve

the whole section on Perspective:

Niceron, (Father Fr., S.J.)

Thaumaturgus opticus.[75]

The number of Duchamp's notes that deal with three, dimensional perspective is actually smaller than the group included under "Perspective" in A l'infinitif.[76] The notes discussed above in connection with a tactile "four, dimensional perspective" can be removed, as should the two purely geometrical notes beginning "-Just as a point intersects a curve" (Salt Seller, p. 89)[77] and "By analogy the flat being2 has a length" (Salt Seller, p. 90). Lastly, the note commencing "The mirror = Shadow projected in 3 dims." (Salt Seller, p. 88) should be connected either with the note based on Jouffret's discussion of shadows or with Duchamp's later thoughts on the fourth dimension in terms of mirrors. Because of its talk of "virtual dimensions," this note is more likely related to the artist's later analysis involving mirrors, and "virtuality" itself as the fourth dimension.

One other note in the "Perspective" section should be dealt with before expanding upon Duchamp's initial reference to the card catalogue at Sainte-Genevieve. This is the drawing of a sphere labeled "Pseudo sphere (Projections from the center)" (Salt Seller, p. 87), which represents the one instance of non-Euclidean geometry in the A l'infinitif notes. As demonstrates by contrast, this drawing of a sphere is not a "pseudosphere," Beltrami's negatively curved model for the two, dimensional geometry of Lobachevsky. Instead, the geometrical figure Duchamp depicts is Beltrami's model for three, dimensional Lobachevskian space in the interior of a Euclidean sphere. Since this interior space has often been termed "pseudospherical space," Duchamp's label is only partially incorrect. Interested in the model for its resemblance to a perspective system with a vanishing point, Duchamp may well have discovered it in Poincare or in the original popularization of the Beltrami construction in Helmholtz's "On the Origin and Significance of Geometrical Axioms" of 1870.[78]

Once the process of elimination described above is completed, the remainder of the notes under "Perspective" do deal uniformly with the three-dimensional perspective that Duchamp was to employ in the lower portion of the Large Glass. Although A l'infinitif does not include perspective drawings, such as that of the "Sieves" in the Green Box, Duchamp had begun making perspective studies in 1913. In addition to the 1913 initial layout of the Large Glass in perspective, the most familiar of these are the two 1914 drawings of the Sieves.[79]

The "whole section on Perspective" of the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve catalogue contained a large number of texts on perspective, but by far the most intriguing was the one singled out by Duchamp, Niceron's Thaumaturgus Opticus. Perspective was the magical element celebrated by Father Jean-François Niceron in his 1646 Latin treatise. In the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve there is also an earlier French text on perspective published by Niceron in Paris in 1638, La Perspective curieuse ou magie artificielle des effets merveilleux. Its subtitle is a French translation of the subtitle for Thaumaturgus Opticus and summarizes the content of the two books: "L'Optique, par la vision directei La Catoptrique, par reflexion des miroirs plats, cylindriques & coniquesi La Dioptrique, par la refraction des crystaux." There are differences between the two books, however, and it was in Thaumaturgus Opticus that Niceron set out to demonstrate his virtuosity in the use of perspective, producing complex drawings which must have delighted Duchamp.[80]

Plate from Thaumaturgus Opticus, one of a series that illustrates the use of perspective for groups of increasingly complex geometric solids. Niceron's cubic solid in the middle of his assembly of forms would have been recognized immediately by Duchamp as the figure adopted on a popular level during the nineteenth century to represent the four-dimensional hypercube. In addition, Niceron's perpendicular projections of his figures onto the wall at the left have created "sections" of the figures by means of shadows, notions which already concerned Duchamp.

Duchamp's personal interests in shadows, mirrors, and glass were all to receive additional encouragement through his researches into traditional perspective. The treatment of shadows is customarily included in perspective treatises, although they are not normally the orthogonal, perpendicular shadows of the Niceron figures, which double as geometric sections. Niceron's Thaumaturgus Opticus does include an appendix on the conventional depiction of shadows, however, and La Perspective curieuse deals extensively with "la catoptrique," the study of the optical effects of mirrors. Although Thaumaturgus Opticus devotes little time to catoptrics, mirrors are a subject regularly discussed in books on perspective. Finally, La Perspective curieuse suggests the advantages of the use of a glass panel in creating perspective, an idea dating back to Leonardo and reiterated in many of the nineteenth-entury perspective treatises at Sainte, Genevieve.[81]

Duchamp gave several reasons for his decision to use glass for The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. These included the appeal of the smooth surface of paint beneath glass, free of touch of the artist's "hand," as well as its pure color. Glass also eliminated the need to paint backgrounds, and, as Duchamp explained, "the glass ... was able to give its maximum effectiveness to the rigidity of perspective."[82] Glass was also ultimately to assist in creating the four-dimensionality of the Bride, but its applicability to three-dimensional perspective must have been emphasized for Du, champ in the perspective books he examined.

Figure is taken from Frederic Goupil's La Perspective experimentale (1860), one of the texts on perspective at the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve. Goupil's figure is typical of the numerous illustrations of the process of drawing on glass, which are descended from Dürer's familiar woodcut from his work on perspective. Glass was essential to Goupil's method of "experimental perspective," and his text included a history of the technique from its origins with Leonardo.[83] The very association of this procedure with Leonardo may have heightened its impact on Duchamp, for there was an active interest in Leonardo among the Puteaux Cubists. Duchamp's brother, Villon, for instance, was reading Leonardo's Treatise on Painting in 1912.[84]

Shadows, mirrors, and glass would all play roles in Duchamp's final understanding of the fourth dimension for his representation of the Bride. In the meantime, he had also begun the study of n-dimensional geometry that was to be the source of his notes in the section of A l'infinitif entitled "The Continuum."

* Linda Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), Chapter 3, "Marcel Duchamp and the New Geometries," pp. 135-145.

Marcel Duchamp and the New Geometries (Part 4)

Marcel Duchamp and the New Geometries (Part 5)

Notes:

[54] See Schwarz, ed., Notes and Projects, p. 1. Certain themes broached in the Large Glass notes would continue to fascinate Duchamp until his death, as the recent Centre Pompidou publication of Notes establishes.

[55] Two other notes by Duchamp were published individually: "Cast Shadows" appeared in Matta's magazine Instead in February 1948; "Possible" was published separately by Pierre Andre Benoit in 1958. See Salt Seller, pp. 72-73, for these notes. Duchamp authorized two different orderings of the notes for the Green Box: one for Hamilton's translation of the Green Box and one for Sanouillet's Marchand du sel. See the preface to Salt Seller, p. viii.

[56] See Schwarz, ed., Notes and Projects, pp. 5, 42. Superscript numbers such as the 4 in "Perspective4" are Duchamp's shorthand for signifying numbers of dimensions, i.e., "four-dimensional perspective."

[57] See A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, p. 88.

[58] Schwarz, ed., Notes and Projects, p. 6.

[59] The major alteration of Schwarz's order is in my placement of his "Note 5," "The plane of the mirror is a convenient way ...," much later in Duchamp's evolution than the date of late 1912-early 1913 that Schwarz implies. See the section "The Final Solution; The Mirror of the Fourth Dimension" below.

[60] Arne Ekstrom described Duchamp's attitude during the arranging of the notes for A l'infinitif in these words in a letter of 16 May 1974.

[61] With the exception of two notes in the Green Box (Salt Seller, pp. 29, 70), all of Duchamp's references to the fourth dimension or n-dimensions occur in A l'infinitif. Aside from one note under "Speculations" (Salt Seller, p. 75) and the note beginning "Perspective4" under "Further References to the Large Glass" (Salt Seller, p. 83), all of these references are to be found in the three sections "Appearance and Apparition," "Perspective," and "The Continuum."

[62] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, pp. 84-85.

[63] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, pp. 75, 83.

[64] Adcock argues convincingly that Jouffret's influence can be detected in a number of Duchamp's notes and projects {"Marcel Duchamp's Notes," chs. 3, 4}.

[65] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, p. 89. Although the typography of Salt Seller makes it appear that this note is a continuation of a note beginning "-Just as a point intersects a curve ...," the two notes are actually separate. That they occur at the bottom of one page and the top of the next in the A l'infinitif text published in 1966 may have caused the confusion.

[66] Jouffret, Traite elementaire, p. 186.

[67] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, pp. 89-90.

[68] Duchamp was definitely interested in perspectives cavalieres, for he wrote a reminder to himself in the note "Cast Shadows": "perspectives cavalieres: voir bouquin." Although they are not exact equivalents, this was translated "isometric projections" by Schwarz for his Notes and Projects version of the note, p. 136.

[69] See Chapter 2, n. 108.

[70] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, p. 88.

[71] Poincare, La Science et l'hypothese, p. 73; The Foundations of Science, pp. 68-69.

[72] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, p. 89. The drawing and the note on "Light and shade" above this note probably also date from this early stage.

[73] Ibid., p. 93. Two labeled drawings accompany this note.

[74] Ibid. This note is a continuation of the note at the bottom of p. 92.

[75] Duchamp, A l'infinitif, in Salt Seller, p. 86. Given his interest in perspective, shadows, and projections, Duchamp may have looked at texts on projective geometry, as well as on the new geometries. As Adcock points out ("Marcel Duchamp's Notes," ch. 4), Jouffret's method for depicting four-dimensional figures relies upon projective geometry. Projective geometry, free as it is of metrical considerations, was recognized by Felix Klein in 1872 as the broadest type of geometry, under which all other geometries including Euclidean and non-Euclidean are subsumed (Boyer, A History of Mathematics, p. 592). On projective geometry and perspective, see William M. Ivins, Art and Geometry: A Study in Space Intuitions (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1946), pp. 103-24.

[76] On the other hand, one note which begins "Analogies between Perspectives3 and 4" (Salt Seller, p. 91) has been placed under "The Continuum," but should actually be grouped with the "Perspective" notes. It represents Duchamp's continuing work with a "four-dimensional perspective," using analogies with the three-dimensional perspective he was studying.

[77] This note consists of only five lines of type and is separate from the Jouffret note, as n. 65 above explains.

[78] See Poincare, La Science et l'hypothese, pp. 83-87; The Foundations of Science, pp.75-78. See also Helmholtz, "On the Origin and Significance of Geometrical Axioms," pp. 48-49, 60-61.

[79] Green Box, in Salt Seller, p. 55. The perspective layout of the Large Glass is reproduced in Salt Seller (p. 18). In addition to the drawing of the Sieves included in the Green Box (Schwarz, Complete Works, cat. no. 216), see also Schwarz, cat. no. 217.

[80] Clair provides an excellent discussion of Niceron and other seventeenth-century perspectivists in "Marcel Duchamp et la tradition des perspecteurs," in L'Oeuvre de Marcel Duchamp, III, 124-59. This essay has been translated as "Duchamp and the Classical Perspectivists," Artforum, XVI (Mar. 1978), 40-49.

[81] Niceron, La Perspective curieuse, pp. 12-13.

[82] Duchamp, as quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues, p. 41. See also John Golding, Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (New York: Viking Press, 1973), p. 68.

[83] See Frederic Goupil, La Perspective experimentale, artistique, methodique et attrayante ou l'orthographie des formes (1860) (Paris: Le Bailly, 1883), pp. 14-16. Leonardo's suggestion for the use of glass is to be found in Part 2 of his Treatise on Painting. See Leonardo, Treatise on Painting, trans. and annot. McMahon, I, 65.

[84] Dora Vallier, Jacques Villon, p. 62. On Duchamp and Leonardo see Theodore Reff, "Duchamp & Leonardo: L.H.O.O.Q.-Alikes," Art in America, XLV (Jan.-Feb. 1977), 82-93.