Aesthetic Experience

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Aristide Nordio (1912-1960) |

Aristide Nordio (1912-1960) |

Aesthetic Experience

Richard Shusterman

The End of Aesthetic Experience (Part 1)*

I

Experience, quipped Oscar Wilde, is the name one gives to one's mistakes. Does aesthetic experience then name the central blunder of modern aesthetics? Though long considered the most essential of aesthetic concepts, as including but also surpassing the realm of art, aesthetic experience has in the last half-century come under increasing critique. Not only its value but its very existence has been questioned. How has this once vital concept lost its appeal? Does it still offer anything of value? The ambiguous title, "The End of Aesthetic Experience," suggests my two goals: a reasoned account of its demise, and an argument for reconceiving and thus redeeming its purpose.[1]

Though briefly noting the continental critique of this concept, I shall mostly focus on its progressive decline in twentieth-century Anglo- American philosophy. Not only because here its descent is most extreme, but because it is in this tradition-that of John Dewey, Monroe Beardsley, Nelson Goodman, and Arthur Danto-that I situate my own aesthetic work.[2] While Dewey celebrated aesthetic experience, making it the very center of his philosophy of art, Danto virtually shuns the concept, warning (after Duchamp) that its "aesthetic delectation is a danger to be avoided."[3] The decline of aesthetic experience from Dewey to Danto reflects, I shall argue, deep confusion about this concept's diverse forms and theoretical functions. But it also reflects a growing preoccupation with the anaesthetic thrust of this century's artistic avant-garde, itself symptomatic of much larger transformations in our basic sensibility as we move increasingly from an experiential to an informational culture.

To appreciate the decline of the concept of aesthetic experience, we must first recall its prime importance. Some see it as playing a major role, avant la lettre and in diverse guises, in premodern aesthetics (e.g., in Plato's, Aristotle's, and Aquinas's accounts of the experience of beauty, and in Alberti's and Gravina's concepts of lentezza and delirio).[4] But there can be no doubt that its dominance was established in modernity, when the term "aesthetic" was officially established. Once modern science and philosophy had destroyed the classical, medieval, and Renaissance faith that properties like beauty were objective features of the world, modern aesthetics turned to subjective experience to explain and ground them. Even when seeking an intersubjective consensus or standard that would do the critical job of realist objectivism, philosophy typically identified the aesthetic not only through, but also with subjective experience.

British military personnel using an improvised telescope stand. No 2 Aircraft Depot, Rang du Fliers, France, July 12, 1918.

"Beauty," said Hume in arguing for a standard of taste, "is no quality in things themselves; it exists merely in the mind which contemplates them," though some minds are, of course, more judicious and authoritative than others. Kant explicitly identified the subject's experience "of pleasure or displeasure" as "the determining ground" of aesthetic judgment.[5] The notion of aesthetic experience moreover helped provide an umbrella concept for diverse qualities that were distinguished from beauty but still closely related to taste and art: concepts like the sublime and the picturesque.

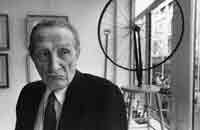

Marcel Duchamp: Bicycle Wheel, New York 1916-1917.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, aesthetic experience gained still greater importance through the general celebration of experience by influential Lebensphilosophies aimed at combating the threat of mechanistic determinism (seen not merely in science but also in the ravages of industrialization). In these philosophies, experience replaced atomistic sensation as the basic epistemological concept, and its link to vividly felt life is clear not only from the German term "Erlebnis" but also from the vitalistic experiential theories of Bergson, James, and Dewey. As art subsumed religion's role by providing a nonsupernatural spirituality in the material world, so experience emerged as the naturalistic yet nonmechanistic expression of mind. The union of art and experience engendered a notion of aesthetic experience that achieved, through the turn of the century's great aestheticist movement, enormous cultural importance and almost religious intensity.

Aesthetic experience became the island of freedom, beauty, and idealistic meaning in an otherwise coldly materialistic and law-determined world; it was not only the locus of the highest pleasures, but a means of spiritual conversion and transcendence; it accordingly became the central concept for explaining the distinctive nature and value of art, which had itself become increasingly autonomous and isolated from the mainstream of material life and praxis. The doctrine of art for art's sake could only mean that art was for the sake of its own experience. And seeking to expand art's dominion, its adherents argued that anything could be rendered art if it could engender the appropriate experience.

This hasty genealogy of aesthetic experience does not, of course, do justice to the complex development of this concept, nor to the variety of theories and conceptions it embraces. But it should at least highlight four features that are central to the tradition of aesthetic experience and whose interplay shapes yet confuses twentieth- century accounts of this concept. First, aesthetic experience is essentially valuable and enjoyable; call this its evaluative dimension. Second, it is something vividly felt and subjectively savored, affectively absorbing us and focusing our attention on its immediate presence and thus standing out from the ordinary flow of routine experience; call this its phenomenological dimension. Third, it is meaningful experience, not mere sensation; call this its semantic dimension. (Its affective power and meaning together explain how aesthetic experience can be so transfigurative.) Fourth, it is a distinctive experience closely identified with the distinction of fine art and representing art's essential aim; call this the demarcational-definitional dimension.

These features of aesthetic experience do not seem, prima facie, collectively inconsistent. Yet, as we shall see, they generate theoretical tensions that propel recent analytic philosophy toward growing marginalization of this concept and have even inspired some analysts (most notably George Dickie) to deny its very existence.[6] Before concentrating on the Anglo-American scene, we would do well to note the major lines of recent continental critique. For only by comparison can we grasp the full measure of the analytic depreciation of aesthetic experience.

II

From critical theory and hermeneutics to deconstruction and genealogical analysis, the continental critique of aesthetic experience has mostly focused on challenging its phenomenological immediacy and its radical differentiation. Although Adorno rejects its claim to pleasure as the ideological contamination of bourgeois hedonism, he joins the virtually unanimous continental verdict that aesthetic experience is not only valuable and meaningful but that the concept of experience is crucial for the philosophy of art. Unlike facile pleasure of the subject, "real aesthetic experience," for Adorno, "requires self-abnegation" and submission to "the objective constitution of the artwork itself."[7] This can transform the subject, thereby suggesting new avenues of emancipation and a renewed promesse de bonheur more potent than simple pleasure.

Here we see the transformational, passional aspect of aesthetic experience; it is something undergone or suffered. Though the experiencing subject is dynamic, not inert, she is far from a fully controlling agent and so remains captive and blind to the ideological features structuring the artwork she follows. Hence a proper, emancipatory understanding of art requires going beyond immediate experience, beyond immanent Verstehen, to external critique ("secondary reflection") of the work's ideological meaning and the socio-historical conditions which shaped it. "Experience is essential," Adorno dialectically concludes, "but so is thought, for no work in its immediate facticity portrays its meaning adequately or can be understood in itself" (AT, p. 479).

In the same dialectical manner, while affirming aesthetic experience's marked differentiation from "ungodly reality," he recognizes that such apparent autonomy is itself only the product of social forces which ultimately condition the nature of aesthetic experience by constraining both the structure of artworks and our mode of responding to them (AT, pp. 320-322, 478-479). Since changes in the nonaesthetic world affect our very sensibilities and capacity for experience, aesthetic experience cannot be a fixed natural kind.

This is a central theme in Walter Benjamin's critique of the immediate meaning of Erlebnis privileged by phenomenology. Through the fragmentation and shocks of modern life, the mechanical repetition of assembly-line labor, and the haphazardly juxtaposed information and raw sensationalism of the mass media, our immediate experience of things no longer forms a meaningful, coherent whole but is rather a welter of fragmentary, unintegrated sensations-something simply lived through (erlebt) rather than meaningfully experienced. Benjamin instead advocated a notion of experience (as Erfahrung) that requires the mediated, temporally cumulative accretion of coherent, transmittable wisdom, though he doubted whether it could still be achieved in modern society.[8]

Marcel Duchamp: Bicycle Wheel, New York, 1951.

Modernization and technology, Benjamin likewise argued, have eroded aesthetic experience's identification with the distinctive, transcendent autonomy of art. Such experience once had what Benjamin called aura, a cultic quality resulting from the artwork's uniqueness and distance from the ordinary world. But with the advent of mechanical modes of reproduction like photography, art's distinctive aura has been lost, and aesthetic experience comes to pervade the everyday world of popular culture and even politics. Aesthetic experience can no longer be used to define and delimit the realm of high art. Unlike Adorno, Benjamin saw this loss of aura and differentiation as potentially emancipatory (although he condemned its deadly results in the aesthetics of fascist politics). In any case, Benjamin's critique does not deny the continuing importance of aesthetic experience, only its romantic conceptualization as pure immediacy of meaning and isolation from the rest of life.

Clearly inspired by Heidegger's critique of aesthetic experience,[9] Gadamer attacks the same two features of immediacy and differentiation, which are even conceptually linked. By radically differentiating the artwork from the sociohistorical world in which it is created and received, by treating it as an object purely of direct aesthetic delight, aesthetic consciousness reduces the work's meaning to what is immediately experienced. But, Gadamer argues, this attitude simply cannot do justice to art's meaning and lasting impact on our lives and world:

The pantheon of art is not a timeless presence which offers itself to pure aesthetic consciousness but the assembled achievements of the human mind as it has realized itself historically. ... Inasmuch as we encounter the work of art in the world, ... it is necessary to adopt an attitude to the beautiful and to art that does not lay claim to immediacy, but corresponds to the historical reality of man. The appeal to immediacy, to the genius of the moment, to the significance of the "experience," cannot withstand the claim of human existence to continuity and unity of self-understanding.[10]

To take the work as merely experienced immediacy is to rob it of enduring wholeness and cumulative meaning through communicative tradition, disintegrating "the unity of the aesthetic object into the multiplicity of experiences" (TM, p. 85) and ignoring art's relation to the world and its claims to truth.

Such critique of immediate, differentiated aesthetic consciousness does not, however, constitute a repudiation of the central importance of experience for aesthetics. Indeed, Gadamer claims it is undertaken "in order to do justice to the experience of art" by insisting that this experience "includes understanding," which must exceed the immediacy of pure presence (TM, pp. 89, 90).[11] Rather than identifying art with its objects as in typical analytic philosophy, Gadamer insists "that the work of art has its true being in the fact that it becomes an experience changing the person experiencing it"; this experience "is not the subjectivity of the person who experiences it, but the work itself" (TM, p. 92), which, as a game plays its players, submits those who wish to understand it to the rigors of its structures.

Although it rejects Gadamer's faith in experiential unity and stability, the deconstructionism of Derrida and Barthes takes a roughly similar stand: its radical critique of firm disciplinary boundaries and the "myth of presence" challenges the radical differentiation and immediacy of aesthetic experience without dismissing its importance and power of jouissance. From a quite different perspective, that of sociologically informed genealogical critique, Pierre Bourdieu attacks the very same two targets. "The experience of the work of art as being immediately endowed with meaning and value" that are pure and autonomous is an essentialist fallacy. Aesthetic experience is "itself an institution which is the product of historical invention," the result of the reciprocally reinforcing dimensions of art's institutional field and inculcated habits of aesthetic contemplation.[12] Both take considerable time to get established, not only in the general social field but also in the course of each individual's aesthetic apprenticeship. Moreover, their establishment in both cases depends on the wider social field that determines an institution's conditions of possibility, power, and attraction, as well as the options of the individual's involvement in it.

What shall we make of the two main thrusts of the continental critique? Aesthetic experience cannot be conceived as an unchanging concept narrowly identified with fine art's purely autonomous reception. For not only is such reception impoverished, but aesthetic experience extends beyond fine art (to nature, for example). Moreover, aesthetic experience is conditioned by changes in the nonartistic world that affect not only the field of art but our very capacities for experience in general.

Marcel Duchamp: Bicycle Wheel, Schwarz edition of 8, 1964.

The second charge, that aesthetic experience requires more than mere phenomenological immediacy to achieve its full meaning, is equally convincing. Immediate reactions are often poor and mistaken, so interpretation is generally needed to enhance our experience. Moreover, prior assumptions and habits of perception, including prior acts of interpretation, are necessary for the shaping of appropriate responses that are experienced as immediate. This insistence on the interpretive is also the crux of the Goodman-Danto critique of aesthetic experience. So when Gadamer urges that "aesthetics must be absorbed into hermeneutics" (TM, p. 146),he is expressing precisely the dominant analytic line.

However, the claim that aesthetic experience must involve more than phenomenological immediacy and vivid feeling does not entail that such immediate feeling is not crucial to aesthetic experience. Likewise, Bourdieu's convincing claim that aesthetic experience requires cultural mediation does not entail that its content cannot be experienced as immediate. Though it surely took some time for English to become a language and for me to learn it, I can still experience its meanings as immediate, grasping them as immediately as the smell of a rose (which itself may require the mediation of gardening and complex cognitive processes of sense and individuation).[13]

The decline of aesthetic experience in analytic philosophy partly reflects such false inferences. But it also stems from confusions arising from the changing role of this concept in Anglo- American philosophy from Dewey to Danto, and especially from the fact that this diversity of roles has not been adequately recognized. Viewed as a univocal concept, aesthetic experience seems too confused to be redeemed as useful; so the first task is to articulate its contrasting conceptions.

III

The contrasting conceptions of aesthetic experience are best mapped in terms of three different axes of contrast whose opposing poles capture all four of its already noted dimensions. First, we can ask whether the concept of aesthetic experience is intrinsically honorific or instead descriptively neutral. Second, is it robustly phenomenological or simply semantic? In other words, are affect and subjective intentionality essential dimensions of this experience, or is it rather only a certain kind of meaning or style of symbolization that renders an experience aesthetic? Third, is this concept's primary theoretical function transformational, aiming to revise or enlarge the aesthetic field, or is it instead demarcational, i.e., to define, delimit, and explain the aesthetic status quo?

My claim is that, since Dewey, Anglo-American theories of aesthetic experience have moved steadily from the former to the latter poles, resulting eventually in the concept's loss of power and interest. In other words, Dewey's essentially evaluative, phenomenological, and transformational notion of aesthetic experience has been gradually replaced by a purely descriptive, semantic one whose chief purpose is to explain and thus support the established demarcation of art from other human domains. Such changes generate tensions that make the concept suspicious. Moreover, when aesthetic experience proves unable to supply this definition, as Danto concludes, the whole concept is abandoned for one that promises to do so-interpretation. That aesthetic experience may nonetheless be fruitful for other purposes is simply, but I think wrongly, ignored. To substantiate this line of narrative and argument, we must examine the theories of Dewey, Beardsley, Goodman, and Danto.

Dewey's prime use of aesthetic experience is aimed not at distinguishing art from the rest of life, but rather at "recovering the continuity of its esthetic experience with the normal processes of living," so that both art and life will be improved by their greater integration.[14] His goal was to break the stifling hold of what he called "the museum conception of art," which compartmentalizes the aesthetic from real life, remitting it to a separate realm remote from the vital interests of ordinary men and women. This "esoteric idea of fine art" gains power from the sacralization of art objects-sequestered in museums and private collections. Dewey therefore insisted on privileging dynamic aesthetic experience over the physical objects that conventional dogma identifies and then fetishizes as art. For Dewey, the essence and value of art are not in such artifacts per se but in the dynamic and developing experiential activity through which they are created and perceived. He therefore distinguished between the physical "art product" that, once created, can exist "apart from human experience" and "the actual work of art [which] is what the product does with and in experience" (AE, pp. 9, 167, 329). This primacy of aesthetic experience not only frees art from object fetishism but also from its confinement to the traditional domain of fine art. For aesthetic experience clearly exceeds the limits of fine art, as, for example, in the appreciation of nature.[15]

Dewey insisted that aesthetic experience could likewise occur in the pursuit of science and philosophy, in sport, and in haute cuisine, contributing much to the appeal of these practices. Indeed, it could be achieved in virtually any domain of action, since all experience, to be coherent and meaningful, requires the germ of aesthetic unity and development. By rethinking art in terms of aesthetic experience, Dewey hoped we could radically enlarge and democratize the domain of art, integrating it more fully into the real world which would be greatly improved by the pursuit of such manifold arts of living.

Marcel Duchamp

Its potential pervasiveness did not mean that aesthetic experience could not be distinguished from ordinary experience. Its distinction, however, is essentially qualitative. From the humdrum flow of routine experience, it stands out, says Dewey, as a distinctly memorable, rewarding whole-as not just experience but "an experience"- because in it we feel "most alive" and fulfilled through the active, satisfying engagement of all our human faculties (sensual, emotive, and cognitive) that contribute to this integrated whole. Aesthetic experience is differentiated not by its unique possession of some specific element or its unique focus on some particular dimension, but by its more zestful integration of all the elements of ordinary experience into an absorbing, developing whole that provides "a satisfyingly emotional quality" of some sort and so exceeds the threshold of perception that it can be appreciated for its own sake (AE, pp. 42,45, 63).[16] An essential part of that appreciation is the immediate, phenomenological feel of aesthetic experience, whose sense of unity, affect, and value is "directly fulfilling" rather than deferred for some other time or end.

The transformational, phenomenological, and evaluative thrust of Deweyan aesthetic experience should now be clear. So should the usefulness of such a concept for provoking recognition of artistic potentialities and aesthetic satisfactions in pursuits previously considered nonaesthetic. It is further useful in reminding us that, even in fine art, directly fulfilling experience rather than collecting or scholarly criticism is the primary value. Nor does this emphasis on phenomenological immediacy and affect preclude the semantic dimension of aesthetic experience. Meaning is not incompatible with qualia and affect.

Unfortunately, Dewey does not confine himself to transformational provocation, but also proposes aesthetic experience as a theoretical definition of art. By standard philosophical criteria, this definition is hopelessly inadequate, grossly misrepresenting our current concept of art. Much art, particularly bad art, fails to engender Deweyan aesthetic experience, which, on the other hand, often arises outside art's institutional limits. Moreover, though the concept of art (as an historically determined concept) can be somewhat reshaped, it cannot be convincingly defined in such a global way so as to be coextensive with aesthetic experience. No matter how powerful and universal is the aesthetic experience of sunsets, we are hardly going to reclassify them as art.[17] By employing the concept of aesthetic experience both to define what art in fact is and to transform it into something quite different, Dewey creates considerable confusion. Hence analytic philosophers typically dismiss his whole idea of aesthetic experience as a disastrous muddle.

* Richard Shusterman; The End of Aesthetic Experience, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 55, No. 1., Winter, 1997, pp. 29-34.

The End of Aesthetic Experience (Part 2)

Notes:

[1] One reason for my interest in this concept is its important role in my pragmatist aesthetics. See Richard Shusterman, Pragmatist Aesthetics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), especially chap. 2.

[2] I also see Joseph Margolis and Richard Rorty as major figures in the aesthetic tradition that shapes my work, but their theories are not so central to the topic of this paper.

[3] See Arthur C. Danto, The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (Columbia University Press, 1986), p. 13; henceforth referred to as PD. I shall also be using the following abbreviations in referring to other works of Danto, Beardsley, Dewey, and Goodman: Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (Harvard University Press, 1981): TC; Monroe C. Beardsley, Aestherics: Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1958): A, and The Aesthetic Point of View', (Cornell University Press, 1982,): APV; John Dewey, Art as Experience (Southern Illinois University Press, 1987): AE; Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968): LA, Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1978): WW, and Of Mind and Other Matters (Harvard University Press, 1984): OMM.

[4] See, for example, the account by the renowned Polish historian of aesthetics, W. Tatarkiewicz in his A History of Six Ideas (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1980), pp. 3 10-338.

[5] See David Hume, "Of the Standard of Taste," in Essays Moral, Political, and Literary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963), p. 234: and Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), pp. 41-42.

[6] See George Dickie, "Beardsley's Phantom Aesthetic Experience," Journal of Philosophy 62 (1965): 129-136. Eddy Zemach also argues that there is no such thing as the aesthetic experience in his (Hebrew) book, Aestherics (Tel Aviv University Press, 1976), pp. 42-53.

[7] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (London: Routledge, 1984), pp. 474,476; henceforth AT.

[8] Though he advocates Erfahrung over Erlebnis, Benjamin is critical of the neo-Kantian and positivist notion of Ecfahrung as being too narrowly rationalistic and thin. My compressed account of Benjamin is based on his essays "The Storyteller," "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire," and "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." All these texts are found in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (New York: Schocken, 1968). Fuller discussions of Benjamin's theme of experience can be found in Richard Wolin, Walter Benjamin: An Aesthetic of Redemption (Columbia University Press, 1982), and in Martin Jay, "Experience Without a Subject: Walter Benjamin and the Novel," New Formations 20 (1993): 145-155.

[9] Challenging the idea that art is something for detached, immediate "appreciation and enjoyment," Heidegger insists that "art is by nature ... a distinctive way in which truth comes into being, that is, becomes historical." It therefore cannot be separated from the world of its truth-disclosure simply for the narrow goal of experienced pleasure. In this sense, Heidegger warns, "perhaps experience is the element in which art dies." See Martin Heidegger, "The Origin of the Work of Art," in Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), pp. 78, 79.

[10] Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method (New York: Crossroad, 1982), pp. 86-87; henceforth TM.

[11] In highlighting the cognitive dimension of aesthetic experience, Gadamer writes: "What one experiences in a work of art and what one is directed towards is rather how true it is, i.e., to what extent one knows and recognizes something and oneself." The joy of aesthetic experience "is the joy of knowledge" (TM, pp. 101, 102).

[12] See Pierre Bourdieu, "The Historical Genesis of a Pure Aesthetic," in Analytic Aesthetics, ed. Richard Shusterman (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989), pp. 147-160, citations from pp. 148, 150.

[13] For more detailed argument of this point, see the chapter on "Beneath Interpretation" in Pragmatist Aesthetics. I develop the arguments further in Sous I'interprétation (Paris: L'éclat, 1994), and Practicing Philosophy: Pragmatism and the Philosophical Life (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[14] Dewey thus sees aesthetic experience as central not only to art but to the philosophy of experience in general. "To esthetic experience," he therefore claims, "the philosopher must go to understand what experience is" (AE, p. 11).

[15] Although I think this is obvious, there is an argument that denies it, asserting that our appreciation of natural beauty is entirely dependent on and constrained by our modern concept of fine art, as indeed is all our aesthetic experience. For a critique of this argument and a fuller discussion of Dewey's views, see Pragmatist Aesthetics, chaps. 1 and 2.

[16] As Dewey later adds, "The experience is marked by a greater inclusiveness of all psychological factors than occurs in ordinary experiences, not by reduction of them to a single response" (AE, p. 259).

[17] Even if we could effect this reclassification, Dewey's definition of art as aesthetic experience would remain problematic. For this experience is itself never clearly defined but instead asserted to be ultimately indefinable because of its essential immediacy; "it can," he says, "only be felt, that is, immediately experienced" (AE, p. 196). For more detailed critique of Dewey's definition of art as experience, see Pragmatist Aesthetics, chaps. 1 and 2.