Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor and Marcel Duchamp

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

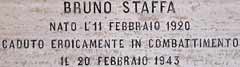

Bruno Staffa (1920-1943) |

Bruno Staffa (1920-1943) |

Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor and Marcel Duchamp

Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor

A Marriage in Check. The Heart of the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor, Even (Part 1)*

I. The Heart of the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor, Even

“I know a Don Juan who is half from the Auvergne and half from Normandy […]”

Francis Picabia, Jésus-Christ rastaquouère.[1]

When I met Marcel Duchamp for the first time, I had just turned twenty-four.[2] Was I an intellectual and an artist? No, but I was good at sport. There were two things that pleaded in my favour: I had had an unhappy love affair when I was an adolescent, and I was leading an idle existence with no idea what to do with myself. But mostly I was in turmoil at the prospect of my parents’ impending divorce. My father wanted to untie the knot in order to marry Jeanne Montjovet—who was still Madame de Morsier—and my mother was in tears all the time, desperately trying to keep her family together and win back the husband she loved.[3] When she had no more energy left to fight, she agreed on divorce. It was a ploy to win time, for she still hoped that this flash in the pan would fizzle out in due course. She had, however, laid down one condition: no divorce until I was married, which was tantamount to putting the thing off indefinitely, since there was no one in view and, better still, I had just given a couple of hopefuls their marching orders—they were impossible anyway. So the atmosphere at home was tense to say the least. Everyone was looking after number one and nobody paid any attention to me while the crisis was on. In the end I felt so dispirited I stopped worrying about my parents’ problems and concentrated instead on my own future. What was I going to do? Get out, run away from home, find a place to live, somewhere I could breathe! But although I was desperate to live my own life, I knew deep down that I could never throw in my lot with the first young man to come my way, especially if he turned out to be a goody-two-shoes I could never see eye to eye with. It also has to be remembered that marriage, for a girl of my generation, was a difficult operation to get right, but the only possible option when one had not chosen the sort of education that leads to a good job and total independence. To complicate matters, “marriage”, in my simple idealism, rhymed with “love”, the one naturally entailing the other. The choice was limited too, most of the young men five or ten years older than us having been killed in the war. Those who came back unconsciously traumatised by the brutality of military action were like demigods to me; they were awe-inspiring, but a little terrifying too. It was one thing to have what it takes to be a hero on the front, quite another to carry the stench of violence and impress a horror of bloodshed upon the sentiments of a young maiden. I was duly reverent, but I was hardly tempted to build my nest under such psychological conditions. Some of my friends succumbed, but not me. I had dreamt of something else. I had not yet come across the tall dark handsome stranger that every young girl hopes will come along. Just meeting eligible types was a problem in itself, but my friends and I would hear nothing of formal presentations arranged by family or well-wishers. So when I learnt that a long-time friend, Germaine Everling, thought I should meet a friend of Picabia’s, a painter like himself and likewise said to be “avant-garde”, I did not exactly back away. I was tempted because he was from a completely different milieu, and I was curious to hear the doctrines and ideas of these eccentrics that everyone around me was laughing about and that I had no contact with.

Marthe Sarazin-Levassor (née Olivié), Henri Sarazin-Levassor, Lydie and their dog “Flic” (slang for a policeman).

Germaine Everling, and her brother and sister, were all childhood friends of my father, and of his brother and sister, their two fathers having made acquaintance during the siege of Paris: they were both in the light infantry and discovered they both had Belgian origins. Their friendship continued undiminished over the years, and their trials and joys were shared by the two families as marriages, births and bereavements succeeded one another. When Germaine was still very young, sixteen or seventeen, she had married Georges Corlin, another friend of my father’s. He worked in the car industry by day, and wrote music reviews for Comoedia in the evenings. The two married couples saw each other often. My mother, a young provincial, was always warmly welcomed by her new friend Germaine. As for their son Michel Corlin and myself, we had spent nearly all our Sundays together ever since we were little, making him my first playfellow. Georges and Germaine’s couple did not, however, survive the war. Germaine confided to my mother that she was having an affair with Picabia and my mother had initially been understanding, then she saw Procession à Séville and was horror-stricken.[4] No! One could not really be in love with someone who had conceived a hoax as monstrous as that! The Dada movement,[5] free love and the birth of Lorenzo finally proved to my mother that Germaine was a fallen woman and one could not continue to frequent someone who had chosen to ostracise themselves from polite society.[6] So when Germaine and Picabia came to Étretat to stay a t the home of the devout Mademoiselle Maigret, my mother adamantly refused to admit the sinful couple into her home, and even to bid them good day on the beach or in the casino. Germaine was cut to the quick; she had hoped for more indulgence since she was only partly responsible for the current state of affairs: Gabrielle Buffet, to whom Francis was still legally wed, did not want to divorce. As for Picabia, he found my mother’s attitude petty and ridiculous, thinking that he was someone to be courted rather than avoided. Relations had become strained, but not to breaking point. My father had recently drawn closer to Francis and Germaine, turning up with Jeanne Montjovet, now that he firmly intended to start a new life with her.

So it is easy to understand why my mother and family should have reacted as they did to the idea of a “date” let alone a “match” suggested by Germaine. It had to be a penniless nobody picked up off the streets, a mere puppet, a pawn in a diabolical scheme thought up by Picabia and Montjovet in order to precipitate my father’s divorce. All hell broke loose! Even before a date had been fixed, my uncles, aunts, cousins, friends and tutti quanti thought it their beholden duty to warn the poor little idiot of the trap that was lying in wait for her. Beware! they said. Anyone coming from those unscrupulous professions was not necessarily an outright crook, but you never can tell, and the whole affair was terribly suspect.

Portrait of Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, c. 1910.

I listened and held my tongue, but that did not mean that I agreed with them. I trusted my father implicitly, confident that he would not have got me mixed up in any risky business, even if he stood to gain his freedom from it. I refused to believe that all humanity could be separated out into two neat categories, with one hundred per cent good guys on one side and the blackest of black ones on the other. It was too naïve! Anyway, though I knew precious little about this Marcel Duchamp person, I was intrigued by his personal history. How curious, a forty-year-old man wanting to get married but unable to find a suitable wife on his own. And how strange to be a painter and temporarily give up painting in order to play chess. Naturally, Germaine had not made a secret of the fact that Marcel Duchamp was seeking to settle down, have a home life and put an end to the life of pleasure he had been leading up to now. She also gave me strong hints to the effect that he had a temporary cash-flow problem. Up to the death of his parents he had received enough parental aid to ensure a meagre existence, but in a move that showed both generosity and lack of foresight, he had used the totality of his inheritance to buy the Brancusi sculptures that John Quinn had collected and which stood to be sold off at disastrously low prices now that Quinn had died.[7] As a result, all that Duchamp possessed was stones, and stones do not bring in the daily bread! I found all that rather appealing, and together with the fact that he was a non-combatant, that he did not worship Mammon, and that he asserted his personality in everything he did, it all constituted favourable circumstances, but most important for me was the fact that he came from outside the narrow circle of gossipy relations that had been hemming me in. Here at last was someone I could confide in, and with whom I could talk about my problems.

The formal introduction took place in an ordinary restaurant, whose name I have forgotten.[8] It was a friendly dinner in the presence of my father, Germaine and Picabia. Germaine asked me a thousand questions, doubtless so that Marcel would be able to deduce certain things about my character; Picabia broached the question of modern art with me. He could not believe that I had never heard of a single contemporary painter bar one or two. He quoted names: so-and-so who sends a painting every year to the salon representing a Breton landscape with pink sheep grazing on purple grass— his pet hate, apparently. No, never heard of him. No more than painter number two, whose canvases dissolve before the eyes like sweets in the mouth, or the painter with nothing but chocolate on his palette and brush, or the portraitist who will only do corpses. Then turning to Marcel, he said: “It’s simply marvellous, to be so completely unaware! She’s a clean slate, a fresh pair of eyes!”

Lydie Sarazin-Levassor (centre) and two friends, c. 1925.

I was not particularly impressed by Marcel on that particular day. I thought he was handsome, friendly, elegant, but nothing special. I was struck by his sober apparel: navy blue suit, pink-striped silk shirt, dark tie. I did not exactly expect him to turn up in a black velvet jacket with a loosely-tied bow and a hat like Aristide Bruant, but still… A little idiosyncrasy would not have surprised me. As far as Marcel was concerned, his first impression—as Germaine later told me—had been: “Ah! She’s quite alright. Simple and straightforward, and she does her hair with a lick and a promise!”

True enough, as I came out of the car the wind had ruffled my hair without my realising it, and it never occurred to me to use the little comb I had in my bag.

The dinner did not leave me with a strong impression, and all I retained was that, all things considered, this “gentleman” was a distinct possibility, but nothing more than that.

Forty-eight hours later, I received a letter by express delivery inviting me to dine at one of the celebrated Prunier restaurants on the corner of the Avenue Victor Hugo and the Rue de Traktir. I must admit that this was the first time ever I was going to dine alone with a young man who was not a member of the family; whatever the outcome, it was a momentous event for me.

And it was a marvellous evening. Marcel used all his charm—he possessed it in abundance, it has to be said—and I left the restaurant head over heels in love with him. I had been seduced by what he had said about his work, his experiments, his friends. I was held enthralled. I had glimpsed a new world of possibility, far more interesting than the daily grind of gossip that I had come to expect from my set. Another thing that excited me was the impression I had that he was very happy to be with me. He said that he had left the United States with no regrets, or very few, mostly for the nightlife, not spent partying as in Paris, but the province of numerous workers whose hidden labours made life simpler for everyone during the day. Shops and restaurants stayed open all through the night. It was possible to buy anything, in any district, at any time of the day or night. Marcel had got into the habit of nibbling a little something before going home to bed and would buy a few household items on the way so as to avoid having to carry them about with him during the day. He missed not having that option in Paris.

Henri Sarazin-Levassor with Jeanne Montjovet, and a pupil of Jeanne Montjovet bottom left, Mougins, c. 1935.

He also missed the comfort of new American designs that had made draughts a thing of the past, and Venetian blinds which screened windows and did away with the need for double curtains, the latter, as I was later to learn, being to his eyes merely “decorative”—a pejorative term for him if ever there was one.

I pointed out to him that in old houses, those built in the eighteenth century for example, wooden shutters tucked behind windows performed the same office as his American blinds. Marcel conceded the point, only deploring the fact that landlords should have been so tight-fisted as to have removed those articles of comfort, forcing people to protect themselves against draughts by textile curtains the necessity of which he abhorred.

That outing made me wonder whether Marcel’s completely negative attitude towards certain everyday inconveniences might not have been prompted by a hidden desire to go back to a former standard of living. As for the people he had known in New York, he was very discreet about them, letting slip not a single name (not that I would have heard of any of them anyway). He let it be clearly understood that he had felt imposed upon by an excess of kindness and thoughtfulness and that everyone had tried to net him for themselves. He was delighted to have escaped and had no intention of going back.

After that first dinner together we were to see each other almost every day. Several times he came to the house to fetch me and we would go out to eat—the start of our gastronomical excursions round Paris which would last right up until we left for Mougins.

Once I started to feel at ease with him, I tried to explain the mental distress I was in, the painful circumstances of my parents’ separation, the actual role I had played in it, and the ignoble role I was accused of playing, the nausea I felt at the reactions of my mother’s close relations, and finally my need to escape which, ultimately, could have led me to fling myself into the arms of the first person who proposed to whisk me away from it all. But my personal concerns did not interest him. After all, he said, there is nothing extraordinary about divorcing, even after twenty-five years of living together, and there will always be someone who thinks they are a victim and so on. I had to accept that what was such a big deal for me did not concern him, that the best thing to do was never to mention it again and, since the page was probably about to be turned anyway, it was more important to think about the future than fret about the past.

“Les Fondrets”, Étretat, 1978. Lydie's bedroom was on the first floor.

That was at the end of March, a fortnight before the Easter holidays which I was going to spend at our villa in Étretat with my friend Édith Nouvion. My mother had come to accept her future son-in-law and was feeling better inclined towards him. There were two good reasons for this. First, she knew the Crottis[9] as they had been living for years in the same building as her sister de Chauffour and she had already received them at “Les Fondrets.”[10] Secondly, she acknowledged that not all Norman notaries[11] are corrupt and that it was possible to frequent Picabia without being a bandit oneself. She came around quite quickly to my proposal of inviting Marcel Duchamp to spend a few days with us, as long as his stay was short and discreet and I did not present him to any of our friends who might be there at the time, seeing that we were not yet engaged.

So Edith and I set off in my little Citroën Trèfle 5 CV, your standard yellow and black three-seater, and Marcel joined us a few days later. Édith, who was not in love, was particularly struck by the state of his clothes: his striped silk shirts, though fashionable, were badly scuffed, his suit showed its age and his coat was shabby and worn. “Your suitor looks like something the cat brought in. He must be terribly poor.”

I did not know what to say in reply, for I had remarked nothing apart from his being correctly dressed and in any case his lack of means did not particularly frighten me since I had few needs myself. The stay was a very merry one. The weather being bad, we were shut up indoors, which made it easy to avoid meeting people. We lit roaring fires in the big fireplace, had delicious meals, shamelessly washed down with the oldest vintages found in the cellar, played mah-jong, cards and chess. We compared the merits of my uncle’s old calvados, matured in wooden casks, with the Napoleon III fine champagne. We emptied whatever we could find in the matter of aperitifs and liqueurs left over from the summer before, and got to know each other. We both knew full well why we had been introduced to each other, and it was not long before we broached the subject of a common future. Marcel had not beaten about the bush when raising the issue of the two flats: the first, his studio, was necessary to him for working and thinking; the other would be my responsibility, mine to look after and live in—and, eventually, with the children. I did not find the idea shocking. Men always have their office outside the home, and why should he not sometimes stay there overnight to finish a job, talk with friends or just take a night’s rest? In any case, although I had decided to take an interest in his work, it would only be to the extent that he wanted to explain it to me. The wives of doctors or lawyers do not feel obliged to study medicine or law when they marry. The “wife and collaborator” is only a viable concept and practical possibility if husband and wife have followed similar paths in life and if what brings them together is a shared professional ideal. It was not our case, and I would have been furious with myself had I trespassed upon a domain that was foreign to me.

We had envisaged announcing our official engagement as soon as we were back in Paris, but before “asking for my hand”—since my father required this custom to be observed—Marcel wanted me to meet his family. I already knew Suzanne and her husband; no problem there. That left the Villons, so Marcel took me to see them the following Sunday. A wonderful visit! Gaston, the eldest brother, radiated kindness and generosity, self-effacing as he was and modest in his manners, blushing like a little girl. What an affectionate welcome! What peace and calm they radiated! Gaby was certainly inhibited, but she greeted me with open arms. She came across to me as sweet, kind and sensitive. The surroundings were extraordinary. It was only a stone’s throw away from the Défense and yet you would have thought you were in the open country. In front of their suburban house there were fields, yes, fields! green fields smelling of freshly-mown hay, and you could hear a goat bleating not very far away. Gaby told me that she bought her milk and fresh eggs at a neighboring farm. Incredible! And all that next door to the factories in Puteaux and the hustle and bustle of the Avenue de Neuilly. How restful and reassuring was the atmosphere in their house in the Rue Lemaître, far from the bohemian, disorderly life that, deep down, I had feared. The Crottis were there too, and Raymond’s tall widow Yvonne,[12] all having a quiet cup of tea. The Duchamp family seemed very close-knit. They had remained very provincial, and lived comfortably, in keeping with their Normandy origins. They were also somewhat reactionary, in marked contrast to the avant-garde ideas they discussed. Little was said of Jean Crotti’s work, or of Gaston’s— and less still of Marcel’s research. I was, however, treated to a tour of the studio adjoining the house. A special favour, for the studio was closely guarded: the Louvre had entrusted a number of paintings by famous artists to Gaston, and he was in perpetual fear lest an accident should befall them.

The tall Yvonne likewise took me round the house she lived in with her brother Jacques Bon, and which had been the home of Raymond Duchamp- Villon. I was particularly struck by the Baudelaire and the horse’s head that sat in state in the main room.[13] I was flabbergasted; never before had I seen anything so striking. There was also the kitchen that had been decorated by friends of Raymond, and I saw there the only work by Marcel that I had ever seen up till then: the celebrated Coffee Mill,[14] which I did not take to at all. I found it disturbing.

Protocol had been observed and all that was left now was for Marcel to officially ask for my hand in marriage. It was unfortunate at the time that Picabia and Germaine had gone back to Mougins[15] and that Gaston or Jean Crotti had not been entrusted with the mission of approaching my father, for Marcel was far too ticklish to go into money matters, and a third party could easily have explained the problem of the Brancusi sculptures: my father would have been understanding, and a fair amount of the money problems that were later to arise would have been avoided. But Marcel, who was nearly forty, was not to be taken for a child: he was an adult who would not be patronised, a man who shoulders his responsibilities and takes his decisions alone.

Portrait of Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, c. 1920-1922.

Their talk together was brief. Marcel stayed for dinner; my mother, although she had to some extent overcome her prejudice against her future son-in-law, nevertheless gave him a very guarded welcome. She still thought that Marcel and Madame Montjovet were hand in glove—whereas they did not even know each other—and it was with deep sorrow that she saw her only daughter, the object of so much love and tenderness, turn against her and fall so stupidly into such an obvious trap. As for the sincerity of our feelings towards each other, she never wanted to believe it, and the quick divorce that was to follow proved her right, on the face of it at least. So, predictably, the dinner was none too euphoric, and even rather frosty to begin with. And yet Marcel was happy and very relaxed and seemed oblivious to all this. He turned on the charm, and my poor dear mother, despite herself, was not insensitive to its appeal. We spoke of Rouen, where my mother had lived till her marriage. We tried to see if we did not know some of the same people there, whether his grandfather, Émile Nicolle, had not frequented my grandfather, the painter Léon Olivié, who had been a close friend of the curator of the museum.[16] The conversation subsequently veered to the subject of painting. My mother apologised for my ignorance in such matters saying that, as she knew I had no talent for art, she had steered me away from such pursuits lest I should become—horror of horrors—the type of young lady that paints watercolour flowers on fans. Little by little, she set forth her own standpoint: the traditionalists bored her; the Impressionists, Manet, Renoir, delighted her, especially Sisley; but as for the Cubists, she just could not figure them out, despite the explanations furnished by Juliette Roche (Madame Gleizes) whom she sometimes met at the houses of friends. My father was happy now the atmosphere was becoming more relaxed. He topped up our glasses with champagne, put in a witty comment here and there, and agreed with my mother that DADA was a huge farce, a well-organised hoax in the style of those invented by artists and writers in their youth to give the bourgeoisie a kick up the pants. We exchanged funny stories about Maupassant and Léon Fontaine, and my mother related anecdotes dating from that period in Normandy with surprising verve and spirit.[17] Everyone laughed and the evening ended much better than it had started.

As soon as Marcel had left, mother said to me: “My poor child, I don’t know whether I should congratulate you or not. He is certainly a remarkably intelligent man, perhaps too much so for you, my plump darling. Though he does seem very attached to his family, I’m not sure that he has a kind heart. I hope you’ll be happy, but I doubt you will. Anyway, it’s your choice, and you’re at an age when you must know what you’re doing.”

All that was left now was to announce the engagement officially, and as soon as possible because Marcel wanted the marriage to be celebrated before the summer. One particular was to cause a delay of several days: I was to be bridesmaid along with Édith Nouvion at Violette Héritage and Bob de Knyff’s wedding, and inaugurate a ravishing sky-blue tulle dress for the occasion. I also intended to wear it at our engagement party, as I did not want to clutter up my future wardrobe with smart dresses that could no longer serve. And so our official engagement was deferred till the beginning of May. Given the imminence of the wedding itself, it was not much of a to-do: the two families simply had afternoon tea together with the future witnesses and some close friends. Marcel sent a superb basket of flowers, in accordance with etiquette. We had to give up the idea of the black charmond,[18] which was to have been a fine piece of bright coal, like Belgian coal, cut and mounted on a platinum ring like a solitaire. Unfortunately, we were unable to find coal of sufficient quality to permit its being cut! We therefore settled on an ordinary ring, which my parents deemed to be a little on the modest side and which, in the end, was exchanged for a very large pearl which was not quite round but impressive all the same.

Now that marriage had been decided upon, there came the vexed question of which religious ceremony was to be chosen, not that the question was in any way vexed. Marcel was an atheist, and though he had been brought up a Catholic, he saw no objection to a Protestant marriage, the Protestant religion being mine, more or less. A few violently sectarian, antipapist remarks by a Protestant minister in charge of my religious instruction had estranged me from the Church and, as a result, I had not been confirmed. I was worried in case I needed to accomplish this act before a minister could solemnize our union, but everything turned out alright in the end. I was friends with the children of Monsieur Maroger, a former missionary and a very open-minded minister in Clichy. So off we went to ask him if he would solemnize our union. He received us very amiably, though he was not unaware that our faith was shaky to say the least, but God’s minister is always there to care for the lost sheep, and the very fact that we sought his blessing could be read as a step on the way towards a return to the fold. He readily accepted to officiate at our wedding and he even agreed, at Marcel’s request, to declare us man and wife without employing the traditional wedding rings, as we had determined upon wedding bracelets. “Oh!” he said, “the use of rings is a relatively recent convention. I would only ask you not to opt for ankle-rings, for it little behoves a minister to grovel on his knees, save in prayer before God.”

It was therefore decided that the ceremony would take place at the Temple de l’Étoile[19] on 7 June. Marcel would have preferred a small, intimate wedding, but I would hear nothing of it. Apart from the childish pleasure of wanting a wedding to be as glorious as possible and with all the frills, such as every little girl dreams of, the circumstances were such that I was keen to assert myself. An intimate marriage would have been cowardly on my part. No, I was not ashamed of my choice, nor of my act, and I had had occasion to observe that intimate weddings were generally followed by births after less than the regulatory number of months. My situation did not call for such drastic measures, and Marcel let himself be won over. It has to be said too that when it came down to details, Marcel did what he could to make me happy and spontaneously agreed to all my whims and wishes. Being myself rather more used to obeying, I could not believe the ease with which I made him give in to my entreaties, and I was never able to convince myself that in reality he could not have cared less. Clearly, what mattered to him was to get married as quickly as possible, and on that point everyone had let him have his way.

I sometimes wondered whether he was not trying to put a barrier between himself and someone else, something definitive that would justify their breakup. But every man has his past history and I was not going to torture myself over that. After all, he was free to choose what he wanted to tell me of his past life. Perhaps later—but what did it matter since we were happy and together, the present was wonderful and the future was ours for the taking.

The short number of weeks between our engagement and our wedding were spent in a frantic rush to secure what was needed: the trousseau, the bridal gown, the bridesmaids, the printed invitations. Marcel insisted that the latter be in a different format from the usual one, in bold with no capitals and not the usual light-faced type. I discovered for the first time how small detail brought out the perfectionist in him.

Marcel was unable to find anybody suitably young in his circle of family and friends to accompany my bridesmaids, so it was decided that they would process two by two, in matching dresses, to escort the bride. As most of my friends were already married, I had to seek my graceful adolescents among a younger generation. What trouble they gave me! The first candidates to have been approached now went back on their word, finding some pretext or other. Hardly had I achieved my quorum of six young girls and chosen their virginal dresses in white organdie set off by pink velvet belts and pink horsehair hats with wide brims, when Zette Piat, my oldest friend, went down with bronchitis. I had to find a replacement as quick as a flash. Having done the rounds of friends and relations, and nobody else being free, I was happy to make do with a young English student who was lodging with the family of a friend. Vera was pleased to accept but as her income was small she shrank from the expense. I had no other option but to give part of the outfit to her on the quiet. It had to come out of my pocket money, which was very vexing as my purse was already almost empty.

Given the housing crisis, it was decided that the young couple would set up home in the studio on the Rue Larrey[20] until conditions improved. It goes without saying that while I was rushing back and forth to the fitting-room, Marcel was busy flat-hunting. He sometimes took me along to visit domestic premises that turned out to be complete fiascos. They would be charging an inflated price for the furniture and fittings, whereas everything still had to be done, including the bathroom. It did not stop us from discussing our idea of the perfect flat. No furniture, just cupboards hidden behind walls of plywood. Marcel taught me to appreciate the beauty of raw materials. No need for exotic wood or other rare and costly materials to fit out a flat that would be pleasant to live in. A plaster wall has a splendour and delicacy of its own if an effort is made to keep it matt and immaculate; whitewood has a delicate satiny grain that needs neither a coat of walnut stain to pass it off as oak, nor thick coats of paint to cover it up completely; a lead pipe can glisten with a dull sheen and add a touch of light where it was not expected, or a gay band of colour if coated with minium (which is not paint but a natural protective medium).[21]

At first I thought his taste for natural things was a reaction against the “refined” aesthetic propounded by the recent Art Deco exhibition. I spoke to him about it: “As far as lizards go, I have only encountered the variety that basks in the sun. What are these lizards décoratifs? Is it a new species?”[22] To which he replied: “If a butcher makes a sculpture out of lard, is it culinary art or culinary lard? And what about domestic lard, and the lard of war?[23] So tell me about the Arts. Art is simply the technical knowledge that goes with a profession. Look it up in the Larousse dictionary. So what are the Fine Arts? All the arts are fine. The knife-grinder’s art is particularly fine, and fascinating with it. But he is an artisan. Artisan, artist, what’s the difference? My hairdresser calls himself an artist, so does the man in the patisserie, but Gaston’s art is manual, so that makes him an artisan.”

His ironic tone suggested that there was much left unsaid, but I did not insist as I feared I might have got it all wrong.

“There is no such thing as ‘decoration’,” he continued. “The whole concept needs to be buried. We take furniture in, that’s all. We buy the things we need for our comfort. Keep desires to a minimum and do away with what is not strictly practical. That’s it in a nutshell: fittings must be useful.”

“No curtains for the windows, then?” I asked.

“It’s impossible to know in advance in what direction the windows will face. Oil-paper, held in place by rubber suction-cups, makes an efficient screen.”

“Granted. What do we lay on the floor?”

“In winter: skins, for they are soft and warm; in summer: rush-matting or straw-matting, for they are cool.”

Then we amused ourselves trying to think up tableware with other shapes and substances than the usual round, porcelain plates. Such as a dinner service consisting of those rectangular photographic developingdishes with a pouring-lip at one corner, to serve for the soup plates, or all the plates. Forks for pickles, with two prongs instead of four. Wooden spoons or the porcelain ones used by the Chinese. As for knives, dear me! The time we spent discussing how to avoid fancy handles, and the ability to cut was a criterion, all the same! One-piece stainless steel knives had not yet been invented. Glasses had to be as ordinary as possible—so that we could break them afterwards, Russian-style! Sometimes we went windowshopping in the Rue de l’École de Médecine where there was a shop that sold laboratory accessories. We would daydream in front of the window display, wondering if there was anything that could be used for cooking among the retorts and beakers that had been blown into so many different shapes and sizes. We laughed a lot, proposing this or that: I was happy to stir with the glass rods, but the idea of using a round hospital basin made of enamel to serve up jugged hare, well no, frankly! The joke seemed a trifle too scatological, but it did remind me of a readymade he had mentioned to me: the urinal which he had called “Fountain”. Such practical jokes, of which he was fond, amused me greatly and they reminded me of the famous evening when Guy de Maupassant served the punch in umbrella stands. Now, what could be more comfortable than a padded bench in a café? We did not know whether it was for a dining room, a dining hall or simply a breakfast corner,[24] but we bought one and fixed it up with the simplest of simple marble-topped tables. Another day, in I don’t know which big department store, we chanced upon a whole series of articles for outdoor use which turned out to be just what we needed. We immediately adopted the idea of hammocks for beds and swings attached to the ceiling by beautiful hempen ropes like the rigging on a ship. A plank of wood on an incline, fixed to the wall, became a writing desk. We were later delighted to learn that Georges Sand used to sleep in a hammock in her study at Nohant and that she wrote on a plank, hinged to a cupboard. The words “salon” and “drawing room” were of course banished: “The ladies may retire to the drawing room”—horrid! A salon is a hairdressing salon, a drawling room and a drunken brawling room.[25] We preferred “parlour”, the talking room, or better still “confervatory.”[26]

On those days, after dinner in a brasserie in the Latin Quarter, we would go to Montparnasse to see Man Ray, an avant-garde photographer who was completely unknown to the French. He was part of that strange American colony that had invaded Paris, a crowd made up of artists and writers who rubbed shoulders with one another but whose contact with the French was limited to waiters in cafés and girls behind counters, excepting a small coterie of snobs who called themselves patrons of the arts. These foreigners criticised our way of life, without seeking to understand it, and said of us in a tone of voice that reeked of condescension: “They don’t live as they should.”[27]

I knew that ever since Man Ray had arrived from New York, Marcel had gone to great pains to help him, putting him up, presenting him right and left to all his friends, backing him up, supporting him in every way possible until he was able to fend for himself. I had been profoundly moved, and saw evidence of a kind-heartedness that could not have been easily extrapolated from the apparent coldness of my future husband.

I did not particularly like Man Ray and thought that he clung like a leech, but I was very touched to see with what affection and deference he treated Marcel. So, almost every evening, after dinner, they began their inevitable game of chess, which could be counted on to last over two hours. I fretted the time away by chain-smoking, waiting impatiently for the moment when we could return to Rue Larrey and be alone again. It was not that chess did not interest me, as has been said of me since, but I was so in love with Marcel that I was jealous when time with him was stolen from me. It seemed to me that these interminable matches interrupted and quite destroyed the climate in which we were living, and I thought that Man Ray was decidedly lacking in tact to monopolise the man I considered to be my personal property. I did not yet know that the escapism procured by playing chess was absolutely necessary to Marcel, like the air he so liked to breathe in deeply, and that the abstract side of speculative thought chases away the petty ideas that cloud the mind. For some people it is telling their beads that allows them to empty their minds. Playing chess was just as indispensable to him as his daily meals. Nor did I know that he absolutely needed to keep his hand moving intelligently, and moving daily, that artist’s hand weaned from paintbrushes. He had at all costs to express himself by means of a tool, whatever it was. It was absolutely imperative for Marcel to do so, for it provided him with a sort of physical liberation, just as his games of chess were the necessary cerebral gymnastics required for his psychic equilibrium.

And all the while the fateful day was approaching. At home, the tense atmosphere had returned. The iron was entering the soul of my poor mother. She withdrew into herself. She thought each hour tolled the death-knell of all that had constituted her love and happiness: her husband and her daughter. I felt very bad about it but there was nothing more I could do for her. Now that all her attention was fixed on her own suffering, she did not try to help me in any way, did not give me any advice, and even avoided talking to me. My father had bought a flat for Jeanne Montjovet and had decreed that he would move in with her on the very day of my wedding. This flat in the Square Alboni weighed on our hearts. We said nothing, nobody mentioned it again, but we thought about it all the time.

As I prepared to move into the Rue Larrey, I had the removal men carry away a very spacious wardrobe, capable of containing linen and clothes, the deal table, my book-binding tools and—unfortunately for me as it later turned out—a small cabinet that was supposed to look japanned. Yes, it was cheap and tacky, but just fine for putting my tools away. And easy to store out of sight, as it was only about 30 cm high, 25 cm long and 10 cm deep. I grant that it was an unfortunate choice, but I had not really been thinking when I jumbled together and carted off everything that was in the little workshop set up in an outbuilding on the Square du Bois.[28] Much as I had been pleasantly indoctrinated into the ways and use of raw materials, I am ashamed to admit that I had not fully understood the importance that Marcel attached to a certain appearance that his den had to have. It was seven floors up with no lift, the latter lying like a corpse in a cage on a ground floor far away. The only lavatory was a seatless toilet, a communal toilet for all the garrets. The fitted carpet was threadbare. The much-vaunted wall plaster was grey and pitted. There was plywood here and whitewood there, a hideous cast-iron stove and a gas-burner of the same metal. All this appeared to me finally as being rather sordid, and could only be considered beautiful in the dreams of an artist whose spirit soared above such base contingencies. True, I had accepted to live there, and true I felt happy and proud to live my life with such an eminently superior person, but the Rue Larrey flat, with its glass ceiling all mucky, well, it was not exactly a palace.

When Marcel saw my furniture arrive, with the inevitable addition of a small trunk and several suitcases, he felt his gorge rise. It was worse than he had predicted. The limit of endurance was reached when he clapped eyes on my little lacquered cabinet. “I might at least have been spared the indignity of that,” he said. I tried to pass the incident off with humour. I tried begging for forgiveness. He would have none of it. For the first time in my life, I saw his friendly, cheerful, handsome face become closed, hard and more and more surly.[29] For my part, I am hot-tempered and easily fly into a passion, but I am quick to forgive and forget, and sulks and grudges are not part of my vocabulary. I could never have imagined that something so insignificant would be held against me as a serious ground for complaint.

The following day, believing the incident to be over, I proposed to unpack, tidy away and arrange what I had brought. I was surprised to discover that Marcel was still bitter: his whole attitude betrayed it, his words were sour and his face retained the cold, hard expression of the day before. I deduced that lodging me in his Rue Larrey flat was a greater sacrifice for him than originally anticipated, and that my presence was going to importune him to no small degree—but it only made me love him all the more, and to think that he was sacrificing himself to save me from the atmosphere at home that I could no longer endure!

Before pushing under the table the old trunk containing all his private treasures, Marcel opened it to dig out some document or other that he needed, and showed me several photos of paintings he had sold in America. I looked, I stared, and I hoped that he would furnish some explanation, because, frankly, I could not make head or tail of what I saw. Perhaps I would learn why he had given up painting? That he should have given up painting did not particularly shock me in itself, as I perfectly understood that one can evolve with time, grow tired of the same medium and seek a new form of expression so as not to become ossified. But it had nothing to do with that. All he told me was what he had already said to me: “In art, there is nothing to understand; you have to feel. It’s a question of liking or not liking. That’s the only question.” Nevertheless, looking at the photo of Nude Descending a Staircase, he blushed slightly and confessed:

“Nobody knows me here, but in America they love what I’ve produced. It’s now worth a fortune and I’m highly-rated,” he added, sniggering. “I sold this painting for 250 dollars, I think, in 1915. It’s perfectly true to say that I was more than pleased with the sum. It was a lot of money at the time, after all, but since then it has been bought and sold several times and the last I heard it fetched several millions!”[30]

“Gosh! How come?” I asked.

“All because of the art dealers. They make their money on the backs of the poor buggers who pour their heart and soul into something that will enrich these worthy gentlemen. It stinks. And there’s nothing to be done about it. Writers and composers receive their royalties for fifty years, in direct proportion to the success of their works, but as for us, the painters and sculptors, we don’t get a penny. We work just so that these fine gentlemen can grow rich. Ask Picabia what he thinks!”

* Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor; Un échec matrimonial. Le coeur de la mariée mis à nu par son célibataire, même, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2007, pp. 21-45.

Notes:

[1] Lydie Sarazin-Levassor quotes from memory; Picabia in fact wrote: “And this reminds me of a curious story I heard from the mouth of a painter who is half from Normandy and half from the Auvergne, a neo- Cubist and a neo-Don Juan […]”, Jésus-Christ rastaquouère (1920), Allia, Paris, 1992, pp. 43-44. Duchamp’s family originated from Massiac in the Cantal before they settled in Normandy.

Picabia’s novel appears never to have been translated into English. “Rastaquouère”: a pejorative word for a rich foreigner who likes to get himself noticed.

[2] At the beginning of March 1927.

[3] Henri Sarazin-Levassor (1880-1961), son of Édouard Sarazin and Louise Cayrol. Obtained a degree in Law in 1900, was called to the bar in Paris, and became secretary to the lawyer Henri Robert. Married Marthe Olivié in 1901. Gave up the legal profession in 1904 to become sales representative and manager for France of the Charleroi-based Belgium automobile company Germain. Resigned to become manager of the French automobile company Panhard & Levassor, and remained with them from 1914 until his death. Was a volunteer in the Supply Corps at the outbreak of the war, but was invalided out in 1915, and went on to set up, at the government’s request, an aeroplane repair facility, known as Sarazin Frères. Was elected Mayor of Étretat in 1924. The firm of Panhard & Levassor had been set up in Paris by René Panhard and Émile Levassor in association with Édouard Sarazin (†1887), who had bought the Daimler patent rights for France.

Marthe Olivié (1881-1954), daughter of Léon Olivié and Marie Frebourg. Educated at the Bon Secours convent, Rouen. Married in 1901. Divorced in 1928. Jeanne Montjovet (1887-1955), opera singer, studied under Vierne. Made her début singing sacred music in 1910. Prince de Broglie Mission in Italy (1915). Sung the most challenging pieces in the classical repertory under the baton of Toscanini and other great conductors at the Augusteo, San Carlo and Scala opera houses. Offered a class at the Brussels Conservatoire by Queen Elisabeth of Belgium (1921). Numerous European tours. Had married the Swiss national Louis de Morsier, director in France of the Milanese publishing house Ricordi, in 1917.

Jeanne Montjovet had left the composer Louis Vierne in 1915.

[4] Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase and Picabia’s Procession à Séville (1912, 1.2 m x 1.2 m) were exhibited at the “Salon de la Section d’Or” exhibition in Paris, at the Galerie La Boétie and at the International Exhibition of Modern Art held from February through to March 1913 inside the former armoury (hence its name “the Armory Show”) of the 69th United States Infantry Regiment, 26th Street, Lexington Avenue, New York. Procession à Séville was given to Germaine Everling. Duchamp sold it at the Hôtel Drouot auction house (Paris) along with other paintings. Formerly in the Prince Troubetzkoy Collection, it is today in a private collection in New York. In her memoirs, Germaine Everling states she had a great liking for this painting (L’Anneau de Saturne, Fayard, Paris, 1970, p. 172). The atmosphere at Mougins (where Germaine lived with Picabia opposite Lydie’s father’s new house) is described in detail (p. 162 to the end).

[5] Sic. To call Dada a “movement” is of course heresy to its supporters.

[6] Germaine Everling and her son Michel Corlin met Picabia in 1917. Their son Lorenzo was born in 1919 [sic]. Picabia became the father of two sons in less than four months. His wife Gabrielle Buffet gave birth to Laurente Vicente on 15 September 1919, and his mistress Germaine Everling (Madame Corlin) gave birth to Lorenzo on 5 January the following year. Picabia and Gabrielle Buffet, a young avant-garde musician, had met in September 1908 and were married in January 1909. Gabrielle Buffet met Duchamp at the end of 1910 or at the beginning of 1911. She finally divorced Picabia in 1931.

[7] Brancusi. Rumanian sculptor. Sought Form in its purest, most absolute state. Eugène Duchamp, Marcel’s father, died in January 1925, on the very evening of the funeral of his wife, Lucie Nicolle-Duchamp. Marcel Duchamp was a friend of Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and bought the Brancusis in the Quinn collection in 1927. It was John Quinn (1870-1924) who, in 1915, had helped Duchamp to find a job when he arrived in New York. Duchamp came back to Paris at the end of February 1927.

[8] Probably the Grand Veneur.

[9] The Dada painter Jean Crotti had married Suzanne Duchamp, Marcel’s sister, in 1919.

[10] The name of their villa in Étretat.

[11] Marcel’s father had been a notary at Blainville-Crevon and then in Rouen.

[12] Born Yvonne Bon, she had married the sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, who had died in October 1918.

[13] Baudelaire dates from 1911 and was exhibited in the Armory Show in 1913. Cheval majeur dates from 1914.

[14] Coffee Mill dates from November-December 1911. In his conversations with Pierre Cabanne, Marcel Duchamp recalled that Raymond Duchamp-Villon had asked “Gleizes, Metzinger, La Fresnaye, and Léger too I think, to paint him little pictures of the same size that together would make a kind of frieze. He asked me too, and I did a coffee mill which I broke up: the powder falls to the side, the gearwheels are at the top and the handle is seen simultaneously et several points in its circuit, with an arrow to indicate direction.” (Marcel Duchamp, Entretiens avec Pierre Cabanne, Somogy, Paris, 1995, p. 38.)

[15] Picabia and Germaine Everling had moved into the Château de Mai in 1925.

[16] After having been a ship-broker and having made a fortune with the expansion of the port of Rouen, Émile Nicolle (1830-1894), Duchamp’s maternal grandfather, devoted himself to painting and more especially to etching. Lydie Sarazin-Levassor’s maternal grandfather was the painter Léon Olivié (1834-1901).

[17] Léon Fontaine and Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) met for the first time at the Lycée Corneille in Rouen.

[18] “Charmond” (charcoal+diamond): English approximation for the French portmanteau word “charmant”, made from the combination of charbon and diamant (coal and diamond) and a pun on “charming”.

“Bright coal”: Lydie Sarazin-Levassor uses the correct term “charbon brillant” for what is known in English as “vitrain” or, just as correctly, “bright coal”. Its surface is shiny.

“Belgian coal” (“flambant belge”) is presumably flammable, bituminious coal, since flambant is the normal French adjective and noun for the type of coal that burns with a flame. Was such coal imported from Belgium or is there a humorous reference to the supposed perversity of the Belgians: a “Belgian diamond” being slang for a lump of coal? Whatever the case, this paragraph testifies to the puns, portmanteau words and oxymorons that must have been the staple of Marcel and Lydie’s conversations.

[19] Protestant churches in Paris are named after their districts. The Temple de l’Étoile still stands at number 54 on the Avenue de la Grande Armée in the sixteenth arrondissement. The “Étoile” refers neither to the Star of David nor to the star that led the shepherds to Bethlehem, but to the star-shape composed of the avenues that radiate from the Arc de Triomphe.

[20] Duchamp had been renting a studio on the seventh (top) floor (no lift), at 11 Rue Larrey, near the Jardin des Plantes, since the beginning of October 1926.

[21] “Trilead tetroxide (known as red lead, or minium) […] is the orange-red to brick-red pigment commonly used in corrosion-resistant paints for exposed iron and steel” (Encyclopaedia Britannica). Duchamp elected to use minium rather than paint in the Large Glass.

[22] Les Arts sounds exactly like lézards. The pun is an old one (Félicien Champsaur and his illustrator dwell on it in Entrée de Clowns, 1884), but it still seems to give pleasure in Paris today.

[23] The punning reaches a climax with “gros lard militaire”, a combination of gros lard (fat slob) and l’art militaire (the art of war). There may be a silent pun: Duchamp employed the word saindoux at the start of his speech and the military slang for a corporal is saindoux (lard).

[24] “Breakfast corner”: in English in the original.

[25] The objectionable word in French was salon. The original portmanteau word was “saoulooner”, from saouler (to get drunk) and saloon.

[26] The original portmanteau word was “discutoir”, from discuter (to talk) and parloir (parlour).

[27] In American in the original. Lélia, André Maurois. In the introduction to his biography Lélia, or The Life of Georges Sand (1952), Maurois wrote: “Kindred minds are brought together by chance meeting and chain reaction, as are kindred hearts.”

[28] The Avenue du Bois (now the Avenue Foch), where the Sarazin-Levassor family lived, abuts on a square with a public garden.

[29] The actress Beatrice Wood, an intimate friend of Marcel Duchamp from 1916 onwards, made a similar remark: “When he smiled the heavens opened. But when his face was still it was as blank as a death mask. This curious emptiness puzzled many and gave the impression that he had been hurt in childhood.” (I Shock Myself: The Autobiography of Beatrice Wood [1985], Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1992, p. 23.)

[30] Duchamp is not exaggerating: one million old Francs is very roughly equivalent to one thousand dollars. Duchamp received 324 dollars for Nude Descending a Staircase, N° 2 , and 972 dollars for the sale of four other paintings (C. Tomkins, p. 118). When Frederick Torrey decided to sell Nude Descending a Staircase, N° 2 in 1919, he was offered 1,000 dollars

(ibid., p. 148).