Marcel Duchamp's Fountain

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Corradino Leri (1879-1958) |

Corradino Leri (1879-1958) |

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain

William A. Camfield

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917 (Part 1)*

Duchamp's Fountain has become one of the most famous/infamous objects in the history of modern art (Fig. 1). The literature on it-counting references imbedded in broader considerations of Duchamp's work-is staggering in quantity, and one might suppose that little more of consequence could be discovered. But an examination of this literature reveals that our knowledge of this readymade sculpture and its history is riddled with gaps and extraordinary conflicts of memory, interpretation, and criticism. We are not even able to consult the object itself, since it disappeared early on, and we have no idea what happened to it. Duchamp said Walter Arensberg purchased Fountain and later lost it. Clark Marlor, author of recent publications on the Society of Independent Artists, claims it was broken by William Glackens. Others reported it as hidden or stolen.[1] We do not even know with absolute certainty that Duchamp was the artist-he himself once attributed it to a female friend-and some of his comments raise fundamental questions regarding his intentions in this readymade. But most critics have not been troubled by these conflicting comments from Duchamp or by the lacunae in our knowledge. Some deny that Fountain is art but believe it is significant for the history of art and aesthetics. Others accept it grudgingly as art but deny that is significant. To complete the circle, some insist Fountain is neither art nor an object of historical consequence, while a few assert that it is both art and significant-though for utterly incompatible reasons.

Fig. 1 - Marcel Duchamp; Fountain, 1917, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, copy negative from The Blind Man, no. 2, May 1917.

In light of these diverse viewpoints I shall attempt to reconstruct what we know about Fountain based on documents at the time of its appearance in 1917 and consideration of relevant historical circumstances.[2]

Given the remarkable interrelationships in Duchamp's work from beginning to end, an obvious risk is involved in any study that focuses on a single object. However, Fountain will not be entirely isolated from the rest of his oeuvre, and the results of this more narrowly focused study will contribute to the whole.

I am indebted to many individuals and earlier studies. Some of the information and ideas to be presented here are not new, but I have expanded that information, ordered, focused, and flavored it with a personal bias. Indeed, this study is the long-suppressed gratification of a desire which arose in the late 1960s when, as a young teacher, I found myself fascinated with the formal properties of Fountain and convinced that Duchamp had achieved a fusion of visual and intellectual properties which made It. a masterpiece in his oeuvre, rather than the amusing or offensive anti-art object It was often portrayed as at that time.[3]

Fountain entered the history of art in April 1917 on the occasion of the first exhibition of the American Society of Independent Artists. Conditions regarding the organization of that Society are germane to the story.[4] To a considerable extent the Society was a direct descendant of such organizations as the Eight, the 1910 Independents Group and the Armory Show - all were formed to provide exhibitions of American art outside the structure of the National Academy of Design and the offerings of conventional art galleries. From the outset, however, the Society of Independent Artists was distinguished by a contingent of French artists and the intent to be an ongoing organization modeled after the French Societe des Artistes Independants. Duchamp was chief among those French artists, but Francis Picabia, Albert Gleizes and Jean Crotti played lesser roles. They had all arrived in New Yor k in 1915, each in his way a refugee from the devastating war in Europe, each discovering that New York was a stimulating city where he could work again.[5]

Duchamp and Picabia lost no time in enlivening the New York art scene - Picabia with his radically new mechanomorphic portraits and Duchamp with his even more unusual work on the Large Glass and readymade sculptures that inhabited his apartment but were also exhibited for the first time.[6] Picabia, who had established a close friendship with Alfred Stieglitz and his associates during the Armory Show, gravitated toward that sphere of influence and participated actively in the Modern Gallery and the magazine 291, activities supported by Stieglitz but directed by Marius de Zayas. Duchamp became more attached to Walter and Louise Arensberg, recent settlers in New York who made a lasting mark through their patronage of avant-garde literature, their stimulating late-night soirees, their outstanding collection of modern art, and their commitment to Duchamp.[7] The attorney John Quinn helped Duchamp too, although he was more important for other artists and authors whose careers had been disrupted by the war.[8] These collectors, patrons, galleries, and avant-garde magazines are an indication of the lively art scene in New York from 1914 to 1918, a stark contrast to Europe, where salons had been suspended, magazines disbanded, and many galleries closed. There was cause to think that while the Europeans were absorbed by the war, the time had come for America to assume leadership in art. Some modernists even hoped that the democratic traditions of America might make this nation more hospitable toward contemporary art.

Serious discussions were initiated in the fall of 1916, and the Society of Independent Artists was incorporated in December 1916.[9] The proclaimed democratic spirit of the Society was reflected in the officers and directors. William Glackens, an original member of the Eight, was president, and three other directors were either members or associates of the Eight - George Bellows, Rockwell Kent and Maurice Prendergast. Only John Marin came from the circle around Alfred Stieglitz, but there were also three women (Katherine S. Dreier, Regina A. Farrelly, and Mary C. Rogers), Walter Pach, who bridged several groups, and six men who frequented the Arensberg salon-Duchamp, Man Ray, John Covert, Joseph Stella, Morton S. Schamberg and Arensberg himself.[10] The initial notice of the Society released in January 1917 underscored the

great need ... for an exhibition, to be held a given period each year, where artists of all schools can exhibit together - certain that whatever they send will be hung .... For the public, this exhibition will make it possible to form an idea of the state of contemporary art ....

The program of the Society of Independent Artists, which is practically self-explanatory, has been taken over from the Societe des Artists Independants of Paris. The latter Society ... has done more for the advance of French art than any other institution of its period . : . The reason for this success is to be found in the principle adopted at Its founding m 1884 and never changed: "No jury, no prizes."

There. are no requirements for admission to the [American] Society save the acceptance of Its principles and the payment of the initiation fee of one dollar and the annual dues of five dollars. All exhibitors are thus members and all have a vote for the directors and on the decisions made by the Society at its annual meetings ....[11]

Encouraged by a surge in membership, the Society set an opening date for April 10, and committees were formed for such activities as publication, education, and Installation. The educational aims of the exhibition were to be extended by public lectures and by a tearoom managed by Katherine S. Dreier with artists present to meet the public. Duchamp, who had become a major organizer for the Society, agreed to decorate the tearoom for Dreier, an artist and an activist in art and social issues, whom he had met at the Arensbergs'. He was also collaborating with his friends Henri Pierre Roche and Beatrice Wood to publish a magazine entitled Blindman, conceived as a forum for opinions and commentary on the Independents' exhlbition.[12]

Arensberg served as managing director for the exhibition, and his apartment was the site of some important meetings.[13] Duchamp was head of the hanging committee - a task for which he proposed a democratic solution of installation by alphabetical order rather than by groupings according to size, medium or style. Waiter Pach, who sponsored Duchamp's coming to America, was treasurer, and Arensberg's cousin, John Covert, was secretary. In that capacity, Covert was responsible for instructions to the artists which are helpful in reconstructing the sequence of events for Fountain.' Works were to be received on April 3-5, and installation was scheduled for April 6 - 9. In order to be listed .in the exhibition catalogue, a white card-properly filled in - had to be received by March 28, and the same deadline was set for photographs from any artist who wished to exercise his right to one illustration in the catalogue.[14]

The special opening was set for Monday evening, April 9, followed by the public opening on April 10. As those dates approached, the public was peppered with press releases stressing the democracy, the vast size, and the importance of the exhibition-2500 works stretching over almost two miles of panels.[15] Although America's declaration of war on Germany usurped the headlines in early April, by all accounts the opening of the Independents' exhibition was a rousing success-save for one episode that generated a heated dispute among the directors and the resignation of Marcel Duchamp. In conflict with its stated principle of "no jury," the directors of the Independents rejected a sculpture, and, as reported in one press account,

Marcel Duchamp ... the painter of "Nude Descending a Staircase" fame has declared his independence of the Independent Society of Artists, and there is dissension in the ranks of the organization that is holding at the Grand Central Palace the greatest exhibition of painting and sculpture in the history of the country.

It all grew out of the philosophy of J. C. Mutt, of Philadelphia, hitherto little known in artistic circles. When Mr. Mutt heard that payment of five dollars would permit him to send to the exhibition a work of art of any description or degree of excellence he might see fit he complied by shipping from the Quaker City a familiar article of bathroom furniture manufactured by a well known firm of that town. By the same mail went a five dollar bill.

To-day Mr. Mutt has his exhibit and his $5; Mr. Duchamp has a headache, and the Society of Independent Artists has the resignation of one of its directors and a bad disposition.

After a long battle that lasted up to the opening hour of the exhibition, Mr. Mutt's defenders were voted down by a small margin. "The Fountain," as his entry was known will never become an attraction - or detraction - of the improvised galleries of the Grand Central Palace, even if Mr. Duchamp goes to the length of withdrawing his own entry, "Tulip Hysteria Co-ordinating," in retaliation. "The Fountain," said the majority, "may be a very useful object in its place, but its place is not an art exhibition, and it is, by no definition, a work of art.”[16]

The brouhaha over Fountain continued to spread for several weeks, and a few corrections and additions appeared in an account in Boston on April 25:

A Philadelphian, Richard Mutt, member of the society, and not related to our friend of the "Mutt and Jeff" cartoons, submitted a bathroom fixture as a "work of art." The official record of the episode of its removal says:

"Richard Mutt threatens to sue the directors because they removed the bathroom fixture, mounted on a pedestal, which he submitted as a 'work of art.' Some of the directors wanted it to remain, in view of the society's ruling of 'no jury' to decide on the merits of the 2500 paintings and sculptures submitted. Other directors maintained that it was indecent at a meeting and the majority voted it down. As a result of this Marcel Duchamp retired from the Board. Mr. Mutt now wants more than his dues returned. He wants damages."[17]

Despite the lively interest of the press, however, the public knew surprisingly little about Fountain. As revealed in these articles, Richard Mutt's true identity was unknown, and no one could have been aware that the sculpture was a urinal because it was not exhibited, did not figure in the catalogue, and was neither reproduced nor described other than by the general, innocuous term "bathroom fixture." Fountain was not reproduced until the second issue of The Blind Man in May 1917 - one month after the conflict began - and it is not yet clear when it became more generally known that Duchamp himself was the artist. With so little available in the public record until publication of the all-important second issue of The Blind Man, the history of Fountain must be sought in contemporary letters and diaries and in subsequent recollections. Unfortunately, the files of the Society of Independent Artists are of no help. They contain no minutes of the relevant meetings, no formal statement regarding Fountain and no letters of resignation. All records except some heavy ledgers were apparently destroyed around 1930 by a fire in the studio of a member of the Independents, A. S. Baylinson.[18]

In a recollection shared with Arturo Schwarz almost fifty years later, Duchamp said the idea of Fountain arose in a conversation with Arensberg and Joseph Stella, and "they immediately went to buy the item."[19] The object selected was a porcelain urinal, presumably manufactured by the J. L. Mott Iron Works. Duchamp stated many years later that the pseudonym "Mutt" came from the Mott Works but was modified because

Mott was too close so I altered it to Mutt, after the daily strip cartoon "Mutt and Jeff" which appeared at the time, and with which everyone was familiar. Thus, from the start there was an interplay of Mutt: a fat little funny man, and Jeff: a tall thin man .... And I added Richard [French slang for money-bags]. That's not a bad name for a "pissotiere."

Get it? The opposite of poverty. But not even that much, just R. MUTT.[20]

There seems to be no reason to question Duchamp's memory of this episode. "Mutt and Jeff" was a popular comic strip, and Mott was a major manufacturer of plumbing fixtures with a large showroom in New York that could have displayed urinals closely resembling Fountain - insofar as may be judged from roughly contemporary illustrated catalogues (Fig. 2).[21]

Fig. 2 - Porcelain lipped urinal, Panama model, from the J. L. Mott Iron Works, Motts Plumbing Fixtures Catalogue ”A," New York, 1909.

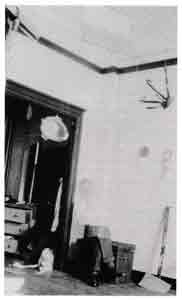

Again in conversation with Arturo Schwarz, Duchamp recalled that the urinal was selected shortly before the opening of the Independents-a claim that is supported by the fact that Fountain did not figure in the catalogue (it missed the March 28 publication deadline), and because no witness to date has recalled seeing it in Duchamp's apartment. It (or another urinal) was in Duchamp's studio at least briefly, however, because there exists a photograph with a urinal suspended from the ceiling along with the Hat Rack and In Advance of the Broken Arm (Fig. 3).[22]

Fig. 3 - Duchamp's studio at 33 West 67th Street, New York, 1917.

Fountain next appeared in the context of installing the Independents' exhibition, and for this stage in the history, Beatrice Wood's diary and memories are crucial. During the week prior to the opening of the Independents, Wood was constantly in Duchamp's company, working with him and Henri Pierre Roche on the magazine Blindman and helping Duchamp with the installation of the Independents, a labor that occupied most of April 6-8. Her laconic diary entries record those activities and the nrst known mention of Richard Mutt and his exhibit:

Friday [April 6] Work at Independents. Lunch Marcel Duchamp at Pollys. Home.

Sat. [April 7] Independent. Dine Roche at Chinese Restaurant. Discussion about "Richard Mutt's" exhibition. Read Roche my articles [for Blindman]. We work at Marcels.

Sun. [April 8] All day at Independent. Lunch. Pach, Friedman, Duchamp, Arensberg ...

Mon. [April 9] Meet Roche at printers to see about Blind Man Magazine at 9-with him all day. Batik. Opening of exhibit. Later jolly crowd at Beaux Arts.[23]

Wood's later recollections provide a more vivid account of one of those days:

Two days before the Exhibition opened, there was a glistening white object in the storeroom getting readied to be put on the floor. I can remember Waiter Arensberg and George Bellows standing in front of it, arguing. Bellows was facing Walter, his body on a menacing slant, his fists doubled, striking at the air in anger. Out of curiosity, I approached.

"We cannot exhibit it," Bellows said hotly, taking out a handkerchief and wiping his forehead.

"We cannot refuse it, the entrance fee has been paid," gently answered Waiter.

"It is indecent!" roared Bellows.

"That depends upon the point of view," added Waiter, suppressing a grin.

"Someone must have sent it as a joke. It is signed R. Mutt; sounds fishy to me," grumbled Bellows with disgust. Waiter approached the object in question and touched its glossy surface. Then with the dignity of a don addressing men at Harvard, he expounded: "A lovely form has been revealed, freed from its functional purpose, therefore a man clearly has made an aesthetic contribution."

The entry they were discussing was perched high on a wooden pedestal: a beautiful, white enamel oval form gleaming triumphantly on a black stand. It was a man's urinal, turned on its back. Bellows stepped away, then returned in rage as if he were going to pull it down.

"We can't show it, that is all there is to it."

Waiter lightly touched his arm, "This is what the whole exhibit is about: an opportunity to allow an artist to send in anything he chooses, for the artist to decide what IS art, not someone else."

Bellows shook his arm away, protesting. "You mean to say, if a man sent in horse manure glued to a canvas that we would have to accept it!"

"I'm afraid we would," said Waiter, with a touch of undertaker's sadness. "If this is an artist's expression of beauty, we can do nothing but accept his choice." With diplomatic effort he pointed out, "If you can look at this entry objectively, you will see that it has striking, sweeping lines. This Mr. Mutt has taken an ordinary object, placed It so that its useful significance disappears, and thus has created a new approach to the subject."

"It is gross, offensive! There is such a thing as decency."

"Only in the eye of the beholder, you forget our bylaws."[24]

There was not time enough to assemble the entire board of directors, but a group of about ten was gathered to decide the issue and, according to a New York Herald reporter, a battle raged up to the opening hour of the exhibition on April 9, at which time "Mr. Mutt's defenders were voted down by a small margin."[25] On the face of it, that decision denied both the principle of "no jury" and the specific rules for exhibition mailed to all members, but there were grounds for suspending all of that in the view of the majority of the directors assembled. Statements quoted in the press and Beatrice Wood's memory coincide on this point: Fountain was not art and it was indecent. Unuttered but surely present in the decision was a concern for the reputation of the Independents in its debut before the American public.

* William A. Camfield; "Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917," Dada/Surrealism 16 (1987), pp. 64-71.

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917 (Part 2)

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917 (Part 3)

Notes:

[1] For the claims of Duchamp and Marlor see Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Belfond, 1967), p. 99, and Clark S. Marlor, "A Quest for Independence: The Society of Independent Artists," Art and Antiquities (March-April 1981), p. 77.

[2] In conjunction with an exhibition of Duchamp's work, the Menil Collection in Houston will publish a modified version of this article as part of an extended text on the history and criticism of Fountain after 1917.

[3] In the fall of 1972 a memorable group of students at Rice University confirmed these perceptions and encouraged this article. Those students were James Courtney, Dean Haas, Robert Hilton, Van Jones, William McDonald, Herta Glenn (Merwin), and Virginia Ralph. I dedicate this article to Herta Glenn.

[4] For the most thorough and reliable account of the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists see Francis Naumann, "The Big Show: The First Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists," parts I and n, Artforum 17 (February 1979), 34-39, and (April 1979). 49-53. Naumann has provided photographs, friendly criticism, and numerous references regarding the Independents' exhibition and Fountain. Special thanks are due for his unstinting generosity. See also Clark S. Marlor, The Society of Independent Artists. The Exhibition Record 1917-1944 (Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Press, 1984).

[5] See the anonymous interview with these four artists in the New York Tribune, "French Artists Spur on an American Art," 24 October 1915, Section iv, 2-3. This interview has been reprinted in Rudolf E. Kuenzli, ed., New York Dada (New York: Willis Locker & Owens, 1986), 128-35.

[6] Duchamp exhibited two readymades at the Bourgeois Gallery, New York, Exhibition of Modern Art, 3-9 April 1916.

[7] For an excellent account of the Arensbergs see Francis Naumann, "Walter Conrad Arensberg: Poet, Patron, and Participant in the New York Avant-Garde, 1915-1920," Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 76, no. 328 (Spring 1980). I am also much indebted to Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, a graduate student preparing a thesis on the Arensbergs, and to Mrs. Elizabeth S. Wrigley, president of the Francis Bacon Foundation, Claremont, California.

[8] Quinn's friendship and his efforts to secure employment for Duchamp are evident in Duchamp's letters to Quinn (John Quinn Collection, The New York Public Library). See also the catalogue for an exhibition organized by Judith Zilczer for the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C., The Noble Buyer: John Quinn, Patron of the Avant-Garde, 15 June-4 September 1978.

[9] In Walter Pach's correspondence with John Quinn, the Independents' project is first mentioned on 9 October 1916, although it is clear that organizational work had begun earlier (John Quinn Collection, The New York Public Library). The certificate of incorporation dated 5 December 1916 is published as Appendix A in Marlor, The Society of Independent Artists, 53-54.

[10] The initial notice of the Society of Independent Artists, Inc., listed the directors us George Bellows, Homer Boss, John R. Covert, Katherine S. Dreier, Marcel Du· champ, Regina A. Farrelly, Arnold Friedman, William J. Glackens, Ray Greenleaf, John Marin, Charles E. Prendergast, Maurice B. Prendergast, Man Ray, Mary C. Rogers, Morton L. Schamberg, Joseph Stella and Maurice Sterne. Walter Arensberg's name was added to that list in the exhibition catalogue. A list published by Clark S. Marlor (The Society of Independent Artists, 58) includes the names of Arthur B. Frost, Jr., Albert Gleizes, Francis Picabia, John Sloan and Jacques Villon. The three French artists, Gleizes, Picabia and Villon, were added at Marlor's initiative because they were involved in the planning of the Society (letter to the author, 2 December 1986).

[11] Announcement entitled "The Society of Independent Artists, Inc.," undated, in the Archives of the Société Anonyme, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

[12] Roche, an author, private art dealer and friend from Paris, arrived in New York during November 1916. Beatrice Wood was a young actress who met Duchamp in September 1916 through the French composer, Edgar Varèse. Roche and Wood contributed most of the texts for Blindman no. 1, which is dated 10 April 1917 but seems to have appeared a few days later. Wood first recorded the Arensbergs' response to it in her diary on 16 April. For the relationships of Roche, Wood and Duchamp see Beatrice Wood, I Shock Myself (Ojai, California: Dillingham Press, 1985).

[13] Covert wrote Katherine S. Dreier on 9 March 1917 to urge her attendance at an important meeting of the directors on 13 March in Arensberg's studio at 33 West 67th Street (Archives of the Societe Anonyme).

[14] These terms and others are specified in a "Notice to Exhibitors" In. d.) mailed to artists over the names of William Glackens and John Covert at the latter's address, 20 West 31st Street, New York, N.Y. (Archives of the Societe Anonyme).

[15] For extensive clippings on the Independents' exhibition see Katherine S. Dreier's scrapbook, vol. I 11915-1917) in the Archives of the Societe Anonyme. See also Francis S. Naumann, "The Big Show."

[16] Unsigned review, "His Art Too Crude for Independents," The New York Herald, 14 April 1917, 6. Several contemporary references in the press to "J. C. Mutt" probably represent a simple error in reporting. Inaccuracies were compounded when an anonymous writer for American Art News confused Fountain with Beatrice Wood's entry Un Peu d'eau dans du savon and claimed it was signed "Jeff Mutt" (American Art News 15, no. 27 [14 April 1917], 1). More puzzling are several contemporary references to a painting entitled Tulip Hysteria Co-ordinating supposedly submitted by Duchamp to the Independents. No such painting has ever appeared, and no further mention of it has been found in documents relating to Duchamp and his friends. Naumann suggests it was a rumor circulated intentionally to mislead the public ("The Big Show," part I, 37 and 39).

[17] Franklin Clarkin, "Two Miles of Funny Pictures," Boston Evening Transcript, 25 April 1917. No further mention of a damage suit has been found, but the identification of "R. Mutt" as "Richard Mutt" correctly reflects Duchamp's intention, and associations of R. Mutt with Mutt and Jeff were prevalent. Harry Conway ("Bud") Fisher's popular cartoon strip on Mutt and Jeff was carried in New York by The World.

[18] Clark S. Marlor, letter to the author, 2 December 1986. A. S. Baylinson (1882- 1950) was a Russian-born artist who became a student of Robert Henri and an early member of the Independents. The tire which destroyed his studio is frequently dated 1930.

[19] Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1979).

[20] Otto Hahn, "Passport No. G 255300," Art and Artists (July 1966). 10. Other accounts for the inscription "R. Mutt" have been offered. Jack Burnham claims it "is a pun or partial homonym for the German word 'Armut,’ meaning poverty" ("The True Readymade?," Art and Artists, February 1972, 27). Duchamp rejected that interpretation, initially attributed to Rosalind Krauss (Otto Hahn, 10). Ulf Linde observed that "Mutt" is similar to a mirror reversal of Tu m’; Duchamp's painting of 1918 which includes shadows of readymades (Walter Hopps, Ulf Linde and Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp. Ready-Mades, etc. 1913-1964 [Milan: Galleria Schwarz, 1964], 63). Rudolf Kuenzli has suggested that "R. Mutt" could refer to "mongrel art" based on the association of "R" with the French word "l'art" and "Mutt" with American slang for a mongrel dog (conversation with this author, 24 September 1987.

[21] The main plant of J. L. Mott Iron Works (founded 1828) was located in Trenton, New Jersey, but it had outlet stores from coast to coast, including major showrooms in Philadelphia and in New York at Fifth Avenue and 17th Street. See the J. L. Mott Iron Works catalogues, Modem Plumbing for Schools, Factories, etc., New York, 1912, and Marine Plumbing, Catalogue "M," New York, 1918. Naumann has identified an outlet at 718 Fifth Avenue, probably the same location ("The Big Show," part I, 39).

Those rare catalogues were made available to the auth.)r by courtesy of Mr. Francis Kelly, recently retired from J. L. Mott, and Laurie H. Sullivan, president of the company, which now specializes in marine plumbing products.

Unfortunately, no company museum or cemetery of old products exists, but among I he few remaining catalogues urinals like the one chosen for Fountain are illustrated in Mott's Marine Department Catalogue "Y," volume II (New York, 19021, 58, and Motts Plumbing Fixtures Catalogue ''A'' (New York, 19081. 417. The latter example (Fig. 2) was first reproduced in George Basalla's excellent article, "Transformed Utilitarian Objects," Winterthur Portfolio 17 (Winter 1982), 194. The 1902 model is described in the catalogue as a "Heavy Vitro-adamant Urinal, 12 x 15 inches, with nickel-plated supply valve, with key stem and 1:y., inch nickel-plated trap" arranged for a continuous flush and retailing for $11. Although several of the wall-hung urinals have shapes compatible with Fountain, few models have flushing rims and ears or lugs for attaching the urinal to the wall which resemble those features on the urinal selected by Duchamp.

[22] This seldom-noted photograph was reproduced in an article by Nicolas Calas, "Cheat to Cheat," View 5, no. 1 121 March 19451, 20. It appears also in Robert Lebel's Marcel Duchamp (New York: Paragraphic Books, 1959), pI. 84.

The apartment in the photograph is the one at 33 West 67th Street occupied by Duchamp from October 1916 to August 1918. Although this photograph could conceivably have been made after the Independents' exhibition, it is curious that no mention "f it has ever emerged in interviews or the correspondence of Duchamp's closest friends, including Arensberg, Beatrice Wood, Louise Norton, Man Ray, H. P. Roche and others. Duchamp said he lost track of Fountain after the Independents. If this photograph was made around late March or early April 1917, then a more precise date can be attributed to Hat Rack.

To date, the original photograph and identity of the photographer have not been found.

[23] I am indebted to Francis Naumann who pointed out the existence of Beatrice Wood's diary and made his copy available, and to Beatrice Wood for her permission to quote from it. Punctuation and spelling in the diary have been retained.

[24] Beatrice Wood, I Shock Myself, 29-30. Beatrice Wood is the only eyewitness to this event who has published an informative account of the argument between Bellows and Arensberg. She has, in fact, contributed several accounts, published and unpublished, which vary in some details but remain consistent in the essentials. The earliest version known to this author appears in Wood's letter to Louise Arensberg on 10 August 1949 in the Beatrice Wood Papers, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C., roll no. 1236, frames 989-90. A similar version, transformed into a dialogue between Bellows and Arensberg, was sent to this author in June 1962. Another version substituting Rockwell Kent for George Bellows was published by Francis Naumann, "I Shock Myself: Excerpts from the Autobiography of Beatrice Wood," Arts 51 (May 1977), pp. 134-39.

[25] Anonymous review, "His Art Too Crude for Independents," The New York Herald, 14 April 1917, 6.