Tzanck Check Investing in Mutt

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Giorgio Barbaro (1807-1887) |

Giorgio Barbaro (1807-1887) |

Tzanck Check Investing in Mutt

Thierry de Duve

Marcel Duchamp, or The Phynancier of Modern Life*

In the whole of the twentieth century there is no less utopian an artist than Marcel Duchamp. And in the whole of it there is no one - with the exception of Matisse, whom Duchamp greatly admired-who could have cared less. Never did Duchamp believe that art had it in its power to promise a better, juster, or happier society, and never did he have to regret that art had reneged on its promises. Long before Yves Klein began selling wind, Duchamp cruelly projected the idea of "establish[ing] a society in which the individual has to pay for the air he breathes," something that didn't prevent him from quietly, tongue-in-cheek, continuing to go through life, breathing. Long before Andy Warhol went shopping and stacked up fake boxes of Brillo, he bought a real bottle rack from a department store and simply waited for time to make it into art and for viewers to give it a price. Long before Joseph Beuys declared that "the silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated," he stopped talking and let others put a value on his silence. He had understood that all the utopias of modernity had already been realized, and thus that they had never been utopias.

Marcel Duchamp; Box in a Valise, 1941. (Photo: Alex Brunelle.)

Beuys was right; it's true that everyone is a potential artist. But does that guarantee that "creativity" and "use-value" even exist?1 No one knows; these are nothing but Ideas, postulates. Nothing says that everyone has a productive faculty within him- or herself, a faculty that is alienated at present but which defines or will define humanity in its generic essence. And nothing proves that it is, in principle, just that everyone be an artist and liberating that everyone will some day become one. Nothing says that humans must work in order to satisfy their needs and must graft their presently reified relations onto this species-determined horizon. And nothing proves that it is just and liberating that they do so. Alienation and reification are wrongs to be righted only on the grounds of these postulates.

Warhol was also right; it is true that art is a business and the work of art a commodity. But does that mean that creativity and use-value don't exist and that one must cynically accept art's absorption into exchange-value? After all Warhol had his utopia as well: if all artists are machines and produce no exchange-value, then all consumers are potential art lovers. But that doesn't prove that they will consume well, and it doesn't promise that the tradition called art will survive its absorption by commodification. It only shows that Yves Klein was wrong and that it was unjust for the artist to claim to own the means of artistic production and to restrict artistic consumption to the buyer. One can cause and suffer wrongs without their supporting postulates being proved.

Marcel Duchamp; Fountain, 1917. (Photo: Alfred Stieglitz.)

Nothing is proved, then, and it is as if Duchamp, skeptic, took off from these observations. It is as if he had, in advance, observed Yves Klein struggling with his wishful thinking and had understood that in fact "to be a painter," or rather to have been one, was the preliminary condition to "being an artist." This is what his own wishful thinking had taught him. And it is as if he had watched Warhol's success and had understood that the spleen of the commodity was the condition for any object whatever to be called art and that the disappearance of aesthetic value into exchange-value was the condition for such an object to have a price. It's what the success of his readymades had taught him. It is as if he had watched Beuys play the père Ubu of creativity and had understood that at the moment when the artist-proletarian saw himself brought home to a Bohemia as unreal as Jarry's Poland, the congruence of the aesthetic field with that of political economy had been perfect, complete, accomplished. Etant donné this lesson, only one question remained: how to make art out of that?

The reference to Jarry is anything but accidental, when we know with what grains of irony the Salt Seller (marchand du sel) seasoned the formula through which he "defined" art: Arrhe est à art ce que merdre est à merde (Arrhe is to art as shitte is to shit). There's nothing left to say, and it is not art but the very congruence of art with economy that the formula analyzes by means of "algebraic comparison." There are hundreds of ways to read that formula, one of which is: "arrhe,"2 as Duchamp practices it, is to art as practiced by the modernists who believe in utopias what King Ubu's oath, merdre (which is also the first word of Ubu roi), is to the substance about which everyone knows that its retention constitutes the "anal-sadistic" personality of all the capitalist misers of the world. The grain of salt that would allow this substance to be taken for a secretion of an artist's creativity is gross indeed. But when everyone can be an artist for the simple reason of free access to the marketplace where what is reified on the one hand is the very thing that is sublimated on the other, the odds are heavy that a large part of what gets traded there is in the nature of the substance in question. (Manzoni didn't miss the opportunity to remind the all too sublime Yves Klein of this.) And since on this market the artist is a proletarian who alienates his own labor power (Beuys's version) or a machine from which things come that, even though without value, have a price (Warhol's), why not kill two birds with one stone and make one's body into "a transformer designed to utilize the slight, wasted energies such as: ... the fall of urine and excrement"? Provided the artist knows how to exploit the unexpected – and least prodigal – resources of his labor power, he will always find himself some businessman or other able to turn a profit from the few quanta of wertbildende Substanz nevertheless spent. Besides, it's better to take care of that oneself. Laziness is the best of foremen and the most fertile of inventors, and humor the most efficient of dealers. It's up to the worker or the machine to supply the waterfall, and up to the dealer to pay the bill for the illuminating gas. Etant donné, then, these two conditions-labor and commerce, the political-economic field-how to make arrhe out of that?

The J. L. Mott Iron Works, Porcelain-lipped urinal, Panama model. 1908.

In New York, in April 1917, a so-called R. Mutt submits a urinal titled Fountain to the hanging committee (of which Duchamp was president) of the newly created Society of Independent Artists, Incorporated. The Society, whose motto was "no jury, no prizes," was open on principle to everyone: the membership card cost a dollar, the annual dues, five. For this modest sum, and on the additional condition of showing the year of his joining up, the little nobody became, in a certain sense, a stockholder of the Société Anonyme (the name would be used by Duchamp in 1920 for the collection he created with Katherine Dreier) from which, on the whole, all American artists exposed to the ostracism of the National Academy hoped to receive dividends. Behold, then, this little nobody who is simultaneously a small-time capitalist in an enterprise licensed to deal in art (the exhibited works were for sale) and an independent artisan otherwise invited to display his know-how. Marcel Duchamp shared this double status with the thousand or so self-proclaimed artists who participated in the 1917 exhibition, with the qualification that he played on one side as on the other an ascendant role. On the stockholders' side, he was one of the twenty founding members and president of the hanging committee to boot; on the artisans' side, he was recognized for his talent as a painter, being the creator of the highly celebrated Nude Descending a Staircase. Yet, giving up this double privilege and making like the little nobody, he submits his entry under a pseudonym. The urinal is refused. Duchamp keeps quiet, waits for the storm to pass, and at the close of the show publishes an unsigned editorial in his little satirical review, The Blind Man, an editorial called "The Richard Mutt Case," which, taking up the defense of Mr. Mutt, reveals his first name.

Duchamp didn't make the Fountain with his own hands, like an artisan; he bought it from its manufacturer, the J. L. Mott Iron Works. The name Mutt signals this provenance with little disguise. "And I added Richard," Duchamp said. "That's not a bad name for a pissotière. Get it? The opposite of poverty." He couldn't have been more explicit, as the signature acknowledges the double status of the nobody who proclaims himself an artist in becoming a member of the Society. On the one side there is the manufacturer, Mutt or Mott, who stands in for the artisan, and on the other Richard, the capitalist, the stockholder. It is as if the latter had placed an order with the former, or rather, as if Richard (alias Duchamp, president of the hanging committee), too lazy or too busy with lighting the entries of his co-stockholders with illuminating gas, had charged Mutt (alias Duchamp, author of Nude Descending a Staircase) with painting The Waterfall, and the latter, hardly less sluggish, had gone to supply himself at J. L. Mott's, whose advertisements ran: "Among our articles of lazy hardware we recommend a faucet which stops dripping when nobody is listening to it." Mott has the item in stock. Mutt hands over the deposit while promising to pay the rest as soon as possible, even adding, quite candidly, that he counts on reselling the object at a profit. "Well that's a peculiar use for a urinal," Mott mutters under his breath, "but it's none of my business. Mine is to sell things that help men do number one, but I sell for the sake of selling and not for them to relieve themselves." And the deal is struck. Whereupon Mutt goes away, his Fountain under his arm, and takes it to Richard and his hanging committee. Richard, just as lazy an administrator as throw up their arms and exclaim: "The Fountain may be a very useful object in its place, but its place is not an art exhibition and it is, by no definition, a work of art." (That's the text of the press release published by the organizers the day after the opening.) The follow-up is very confused, and the versions of the facts vary. Here's one (certainly false, but accredited by Duchamp): another Richard comes along, a friend of the first (in fact his name was Walter C. Arensberg, art collector), and asks about the object of the scandal. Nobody can tell him anything. "I want to buy it," he says without even having seen it. They find the object behind a partition and Arensberg, big spender, hands over a blank check, saying, "Fill in the amount yourselves." Upon which, flanked by Duchamp and Man Ray, he leaves the room "holding the new acquisition as though it were a marble Aphrodite." Mutt goes back to Mott's and pays the balance. Richard resigns from the Society and never cashes his dividends. Arensberg loses the urinal (if he ever had it). And Duchamp has only to wait. He had his reply to the speculation he had jotted down as early as 1913: "Can one make works which are not works of 'art'?" The answer was no, since speculation there certainly had been.

Marcel Duchamp; Vest for Benjamin Péret. 1958.

Taking it from the top: arrhe is to art what shitte is to shit. The art that Mutt practices in working as little as possible, but in making his down payment (des arrhes) to Mott, is to the art of those who work and believe in creativity what speculation is to production, what Phynance (as Jarry spelled "finance" in Ubu roi) is to political economy. The word arrhes, which means deposit, or down payment, exists only in the plural. Duchamp writes it in the singular, adding: "grammatically, the arrhe of painting is feminine in gender." Here's how the word becomes triply specific, then: as a name for money it loses its character of general equivalency and signifies the singular advance on a singular payment; as the homophone for the word art it only refers to painting, specifically, and not to the arts in general; as a gendered word, it designates only half of mankind and shows it to be female. Now, "-one only has: for female the urinal and one lives by it.-" This is in The 1914 Box, three years before Fountain. Virgin and Bride are titles of paintings between which, in August 1912, Duchamp painted The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride, and after which, in October, he gave up painting and found himself a job on the labor market as librarian "in order to get enough time to paint for myself." Now, of his strange activity as "arrhtist" who "paints for himself," who composes aleatory music and draws plans for his Large Glass but doesn't paint any longer, nothing or very little lands on the market between October 1912 and the 1917 Independents where ordinarily the specific work of an artisan-painter is exchanged for general currency. And when Fountain (feminine, just like Virgin and Bride) makes its appearance, there is no longer either painting or artisanship. Duchamp has made art, without its belonging to one of the arts, no more to music or to architecture than to painting; not even to sculpture. Moreover, he has done nothing at all; he has bought a readymade object whose manufacturer,]. L. Mott, didn't make either. Those who made the urinal neither made art nor tried to do so; they are the workers whose creativity Mott bought on the labor market.

The word "readymade" comes from the garment industry. Duchamp didn't invent it, he took it, ready-to-wear so to speak, to dress up the snow shovel he had just bought from a New York hardware store in 1915. In the Theories of Surplus Value (Book IV of Capital) Marx, who as always liberally supplies himself with examples taken from the industrial avant-garde of his age-and the garment industry is one-differentiates productive from unproductive labor. The artisan-tailor to whom the cloth for a pair of pants is brought and who is paid for his services is an unproductive worker, he says, while the worker-tailor employed by a merchant-tailor who derives surplus value from his labor is a productive worker. In the same way Mutt, commissioned by Richard to paint a Waterfall, is in the situation of Marx's artisan-tailor, and Mott's worker, who fabricates the Fountain, is in the situation of his worker-tailor. The artist who works for himself, for his pleasure or because he feels it a necessity, is an unproductive laborer, and it's important that he remain so if he doesn't want to end up as a pieceworker in the culture industry and mortgage his freedom. In other words, it is vital that he remain an artisan. Is that to say that he has to paint, to do handiwork, "to grind his chocolate himself"? Is it to say that he must resist the division of labor to the point of taking everything into his own hands, from the grinding of pigments all way through the vernissage? Marx's artisan-tailor is unproductive because he works to order, because he is brought the cloth for the pants and because it's his services that are paid for. This artisanship is a holdover from precapitalist relations of production. But if the artisan has his own cloth samples, if he has invested in a sewing machine, if he has his list of suppliers-and there is no lack of thread and weaving mills in Marx - he is already on the way to small business. In the same passage from Capital, Marx shows what artisanship has become or is in the process of becoming when it survives as an archaism walled off within the surrounding capitalist mode of production. He points out how the small artisan who works on commission sees, whether or not he wants to, whether or not he knows it, the social division of labor penetrating his own body, and lives out his own activity in the mode of division because the division of labor and of capital is the dominant mode of social relations. He is a capitalist owner of his own means of production who employs himself as wage laborer, buying his own labor power, exploiting his own overtime and pocketing the surplus value thus created. The predictable outcome of this contradiction, Marx attests, is that either the artisan prospers, ending up hiring workers and becoming a boss in his turn, or he fails, losing his means of production and ending up in the employ of someone else.

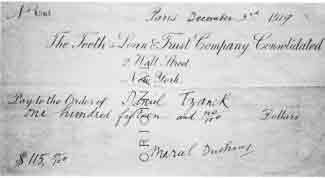

Marcel Duchamp; Tzanck Check, 1919.

But this is not the situation of artists, or when it is, we stop talking of art in any ambitious sense of the word. Their situation-and whatever they may do, whether they paint, write, compose, or are content to put the air they breathe in vials or to can other secretions of their labor power - is to lead, against all odds, the life of an independent artisan. This has nothing to do with what they make or with the quality of their work. It has hardly more to do with their suffering or their pleasure. Those who balk at the division will make it a point of honor to slick up their work all the while decrying the decline of tradition (these are the academicians). Those who find it intolerable to be divided will identify with the proletarian in themselves without seeing that the capitalist is to be found there as well, and will look for the reconciliation outside, for example in "social sculpture" (as with Beuys). Or if they are masochists they will identify with the capitalist, without seeing that they exploit the proletarian in themselves (as with Klein). And if they are really clever they will take their stakes out of the game by making themselves into a machine (as with Warhol). But all of that is beside the point. To lead the life of an artisan without suffering or pleasure, without promising or betraying, is to live one's life as an artist in the mode of division. It means pushing away the pain of the artisan who suffers from having to exploit himself if he wants to survive, from having to mess up the job to the point of losing the pleasure and pride he gets from his work, and from having to abandon the traditional gestures of his craft to the benefit of makeshifts consuming less labor time, in a sort of existential mise-en-abyme for which Duchamp had the knack and through which he registered the division of labor that tears the artisan apart, separating him from himself: "Given that ... ; if I suppose I'm suffering a lot . . . " (This is in The 1914 Box, also.) When Duchamp gives up painting in 1912 and becomes a wageworker at the Ste. Genevieve Library "in order to paint for myself," he divides up the productive and unproductive laborers within himself. Up to that point it's nothing but a lifestyle; he has still to make a life out of it, and out of this life to make his oeuvre. Duchamp the employee makes no claim to art and Duchamp the artisan has stopped producing paintings. Registered: Mott's worker stakes no claim to art and Mutt the artisan no longer paints. Down with the artisan-painter whose Nude Descending a Staircase and even more The Passage of the Virgin to the Bride had shown his talent. Down with tradition, down with the nostalgic clinging to an outmoded craft pursued under hostile conditions. And up with "the arrhe of painting," in the singular and the feminine. How to make Phynance out of that?

Let's take up once again the fable of la Fontaine (for it's above all a moral tale, whereas creativity is a myth and the artist-machine a fiction): At the beginning of the story Marcel Duchamp is R. Mutt, but this we won't know until the end. R. Mutt is like the little nobody who proclaims himself an artist in taking out his membership in the Society; he divides himself into a stockholder and an artisan, Richard and Mutt. Richard is like Arensberg, both of them "big" stockholders in the Society (both founding members) and both collectors (Richard is president of the hanging committee and future founder of the Société Anonyme). Mutt is like Mott, artisan-painter or small industrialist. As artisan Mutt suffers from his person's being divided into an exploited worker and a merchant who pockets surplus value. As industrialist Mott doesn't suffer, he exploits his workers. Mutt envies Mott and fears for his trade. For a year now he hasn't stopped telling himself that he should paint (qu'il peigne),3 but his Chocolate Grinder is already mortgaged and he is no longer anything but its nominal owner (says Marx). Feeling that he will soon have nothing but his creativity to sell, he withdraws his savings, stakes his all, and subcontracts. Mutt is once again like Mott, a merchant, alternately buyer and seller: Mott buys labor power and sells "items of lazy hardware," amongst which is a "faucet" that Mutt buys. At the end of the story Mutt has sold the "faucet" under a new label to Arensberg for a price virtually without a ceiling. Mott, who has got wind of the affair, just can't believe it. He gets after his workers with a prod; yet never could he extract such surplus value out of them. He shakes his head, muttering that even if he knows something about production, he understands nothing of Phynance. His workers have also got wind of the affair and among them there is one who chuckles. On Sundays he paints "for himself," and for the modest sum of $6.00 he took out his membership in the Independents. His name? R. Mutt.

Marcel Duchamp; Fountain, 1938. (First miniature, maquette.)

Thus does Duchamp render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's: to Mott his means of production, which by nature are neither more nor less artistic than the brushes and tubes of paint are for a painter; to Mott's workers their labor power, i.e., their creativity, which is neither more nor less entitled to take the place that talent had in classical aesthetics than the Independents have the right to call themselves artists through wishful thinking; and to the modern artists their resistance to the destruction of their craft, which is neither more nor less justly defined by the technical specificity of the division of labor ("the bachelor grinds his chocolate himself") than by its social generality ("separation is an operation"). But Duchamp renders, as well: to Beuys the myth of creativity; to Warhol the fiction of the machine; to Klein the emptiness of exchange-value and, need we add, to Marx what belongs to Marx. Yes, everyone is an artist; no, artists don't work; yes, the wish to proclaim oneself an artist is only a wish. Yes, the proletarians are alienated; yes, the relations of production are reified; yes, dialectical materialism claims that a just practice proves a theory correct and viceversa. When the congruence between the aesthetic field and the field of political economy is perfect, there is nothing left by to make this visible; but that proves nothing. It was up to Duchamp to show this congruence, and in showing it, he rendered to everyone what belonged to Duchamp. And he, what did he pocket? The fable isn't over. Who cashed Arensberg's blank check? Apparently no one; the check was fabulous in more senses than one. Duchamp, in any case, wanted to cash nothing, not even to take out the right to speculate on what he'd just made. Speculation had already taken place, and the profits went up in smoke. And when it would occur again it would be for the benefit of Sidney Janis and Arturo Schwarz (who made replicas of Fountain), and for the pleasure of those art historians forced to speculate on what really happened with this "faucet which stops dripping when nobody is listening to it" but which-isn't that right, Marcel?-drips at the expense of those listening.

Fables are worth what they're worth and this one isn't even supported. We don't know how things really happened, but at least we know that it wasn't like this. The urinal wasn't behind a partition and Arensberg didn't buy it. It was at Stieglitz's to be photographed and the real Duchamp, less altruistic than the character in the fable, had certainly decided to draw interest on his investment. The question is one of knowing to what extent we are speaking through "algebraic comparison" and to what extent the arrhe of phynance has been superimposed on the art of finance. Should the mapping of the two on one another erase their difference in kind, then Duchamp would be nothing but an opportunist, cleverer than the others. Fables, after all, are worth what their moral is worth, and it's in the real world that the moral is tested. Thus we must find the counter-proof to Arensberg's fabulous blank check. The Tzanck Check could be one. In December 1919, in Paris, Duchamp goes to his dentist, Daniel Tzanck, and pays for his care with a fictive check, wholly drawn by hand. Tzanck, who is also a collector and very active in Parisian avant-garde circles, knows very well what he is accepting for payment. In fact there are two transactions. Like any other dentist Tzanck presents his bill and receives a check in return. But as a means of payment the check is worthless. Like the owner of the restaurant where Paul Klee ate for years in exchange for his paintings, he lets himself be paid "in kind," that is, in works of art. But this particular work of art is a check, and a check is not very gratifying when it comes to aesthetic pleasure. In accepting it the dentist renounces being paid and it is not exactly his services that he exchanges for money but the price of his services, already expressed in money, which he barters against a Dada Drawing (as Picabia called it) not redeemable at the bank. Duchamp obviously knows as well as Tzanck what he is proposing for payment. He suspects that if Tzanck-like Klee's restaurant owner no doubt accepts a work of art in payment for his care, this is not only because the art lover in him, the craftsman who knows what work well done means, has instinctively recognized the fine workmanship of the drawing the artist offers him, but also because the collector in him has instinctively recognized the speculative potential of the deal. Indeed, doesn't Duchamp suggest to him that a bank exists where the Tzanck Check is redeemable? It's the one on which it's drawn, The Teeth's Loan & Trust Company, Consolidated, which lists its legal address as 2 Wall Street, New York. Here we can savor Duchamp's marvelous humor. In inventing a New York bank (a strange thing since we're in Paris), he cloaks with English the fact that the name of the bank articulates exactly the nature of the exchange and of the complicity that forms between the two men: "I loan you my teeth, and in return you give me your trust, and thus will our relations be consolidated."

Marcel Duchamp; Fountain, 1938. (From second miniature edition.)

For twenty years the check stayed in the dentist's collection. During these twenty years Duchamp breathed, played chess, took part in a surrealist exhibition here and there, and, discreetly but not apologetically, performed as a broker. He sold an impressive number of modern works of art, many his own, to various people including Arensberg, his sidekick since the Richard Mutt affair. The war was approaching and the moment came to pack his (boîte en) valise. In 1940 he tried to interest Arensberg in the Tzanck Check-drawn up in 1919 for $115.00 -even writing him that his dentist "would be delighted to accept $50.00 to send it to you." So much for finance: quite a shark, this Duchamp, when it was a matter of playing go-between for two of his collectors. Perhaps Tzanck had not been faithful enough to him (he only owned one other work by him and as chance would have it an investment of the same type, to wit, the Monte Carlo Bond). Arensberg, apparently, didn't want the check. Duchamp then approached Daniel Tzanck and bought the check back "for a lot more than it says it's worth." So much for phynance: the artist had paid his dentist's bill in full, but as a check to be guaranteed on trust, arrhe (the down payment) required the balance.

The moral of a fable isn't dissipated within the real world, it returns to the fable, through "symétrie commanditée." This is Duchamp's expression and it brings finance back to phynance. A commandite is an investment in a joint-stock company with liability only for the sum invested. And this kind of company is a commercial enterprise formed of two sorts of partners; the first (the investing silent partners) bring capital without taking part in the running of the company; the others (those invested) are jointly responsible for all legal debts. In Duchamp's limited partnership we once again meet up with all the characters from the fable, as from real life: Richard/ Arensberg investing in Mutt/Mott, and symmetrically, Duchamp investing in Tzanck. When he buys the check back from him he is not liable for any possible losses on the dentist's part. Arensberg had been the fabulous investor, right from the beginning. It was fair for the one who had offered a virtually limitless price for a urinal he had never possessed to assemble his protegé's work as completely as possible. But the latter is caught up in still another enterprise: a commandite is also a typesetters' collective working by the job. One month before making up the Tzanck Check Duchamp put the letters L.H.O.O.Q. in his composing stick in order to title a somewhat mustachioed reproduction of the Mona Lisa. Now the typesetter needs the Tzanck Check to have it reproduced for the Boîte en valise. He had understood how profitable it would be to keep his complete works to himself in the form - the lightest and most liquid possible-of a portable museum composed of reproductions. For Arensberg, the gold in the safe; for Duchamp, the fiat money backed up by it. He coins money on the "Arensberg Bank," or on the "Mary Sisler Bank" -in short he runs off reproductions of the works that his most faithful collectors have accumulated the way others write checks on their bank accounts. And this, dear reader, is how all the symétries commanditées will be fulfilled and how that which belongs to Caesar will be rendered unto Caesar.

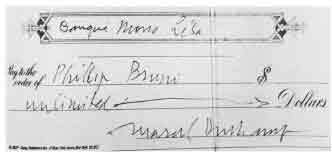

Marcel Duchamp; Bruno Check, 1965.

It's a certain Phillip Bruno who in 1965 cashed Arensberg's fabulous check. The event took place during the exhibition of Mary Sisler's collection at Cordier & Ekstrom (Not Seen and/ or Less Seen of! by Marcel Duchamp/ Rrose Selavy, 1904- 1964). Included there was L.H.O.O.Q. echoed-through symétrie commanditée by the "shaved" Mona Lisa which served as the invitation to the opening. The Tzanck Check was there as well, having in the meantime traveled from Duchamp's wallet to those of Patricia Matta, Arne Ekstrom, and finally Mary Sisler. The story doesn't tell if Phillip Bruno collected anything besides reproductions; in any case the fact remains that he made the catalogue into an album into which, without covering over the photographs, he pasted all the press clippings about the exhibition he could gather. He wished to obtain a Duchamp autograph and, with a paper clip, he whimsically attached a check blank to the page where the reproduction of Tzanck Check appeared, opposite the mustachioed Mona Lisa. Playing the innocent, he presented Duchamp with the book opened to the page in question, awaiting his autograph. Of course Duchamp signed the check for him, filling in the amount: "unlimited"; and the bank (French this time although we're in New York): "Banque Mona Lisa."

The Mona Lisa Bank is the Louvre. Every artist, even and above all the enfant terrible of the avant-gardes, writes checks on tradition. They only have the value of that with which he or she repays tradition. For the arrhe of painting posterity will pay the balance, if it has enough of a sense of humor. The Mona Lisa, with and without mustaches, belongs to it. The artist has put his papers in order and organized his estate: to Leonardo the painting and to the culture industry the right to print it on T-shirts; to Rrose the enigmatic smile and to Mona the hot pants; to the cut-up Georges Hugnet the mustaches and to Marcel Duchamp the razor blades that have "cuttage" in reserve. He could recall that his only utopia had been to "establish a society in which the individual has to pay for the air he breathes" and leave to his creditors the bother of "cutting off the air in case of non-payment." He discovered for himself that he had breathed enough. On October 2, 1968, age took charge of quietly blowing out the candle. Sélavy, right? and anyway, it's always the others who die.4

(Translated by Rosalind Krauss)

* October, Vol. 52, Spring, 1990, pp. 60-75.

Notes:

1. This is the fourth section of a four-part study of Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, Yves Klein, and Marcel Duchamp, titled Cousus de fil d'or (Sewn with Golden Thread), ViIIeurbanne, Art-Edition, 1990. October has published the first three parts: "Joseph Beuys, or The Last of the Proletarians," no. 43 (Summer 1988); "Andy Warhol, or The Machine Perfected," no. 48 (Spring 1989); and "Yves Klein, or The Dead Dealer," no. 49 (Summer 1989).

2. Translator's note: les arrhes (a plural noun), which means a deposit or down payment, is homophonic with art in French.

3. Translator's note: Duchamp's readymade Peigne, or Comb, is homophonic with the subjunctive of peindre, to paint.

4. "D'ailleurs c'est toujours les autres qui meurent, " epitaph on Duchamp's grave in the cemetery of Rouen.