The Reunion of Electronic Music and Chess

sitemap

drawings

paintings

installations 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

projects

reviews

|

||||

|

The Reunion of Electronic Music and Chess

Lowell Cross

Reunion: John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Electronic Music and Chess

The year 1999 marks the thirty-first anniversary of Reunion, a performance in which games of chess determined

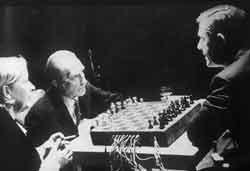

the form and acoustical ambience of a musical event. The concert—held at the Ryerson Theatre in Toronto, Canada - began at 8:30 on the evening of 5 March 1968, and concluded at approximately 1:00 the next morning. Principal players were John Cage, who conceived (but did not actually “compose”) the work; Marcel Duchamp and his wife Alexina (Teeny); and composers David Behrman, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor and I, who also designed and constructed the electronic chessboard, completing it only the night before the performance. Except for a brief curtain call with Merce Cunningham and Dance Company in Buffalo, NY the following month,[1] Duchamp made his last public appearance— in the role of chess master—in Reunion.

Misconceptions

In the intervening 31 years, more fiction than fact regarding Reuni on has appeared in documents about Cage and Duchamp, even from the pens of authors with prestigious reputations. Nicolas Slonimsky wrote in the 1978 edition of Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians:

He [Cage] also became interested in chess and played demonstration games with Marcel Duchamps [sic], the famous painter turned chessmaster, on chessboards designed by Lowell Cross to operate on aleatory principles with the aid of a computer and a system of laser rays.[2]

Cage and Duchamp played only one public “demonstration” game, the one in Reunion, and I have built only one such chessboard to date (I am building a second one in 1999). We used no computer in conjunction with that chessboard and we used no system of “laser rays.” (My development of the first “laser light show” began during the following fall and winter [1968–1969]; I collaborated in that project with the sculptor and physicist C.D. Jeffries at the University of California, Berkeley and, eventually, with Tudor.[3])

In his Cage biography, The Roaring Silence - John Cage: A Life, David Revill wrote:

Early in 1968 Cage realized Reunion. A number of sound-systems which operated continuously were prepared by Tudor, Mumma, and David Behrman. The sounds varied according to the position of pieces on a specially prepared chessboard built by Lowell Cross of the Polytechnical Institute in Toronto. The gates switched by the pieces triggered a passage of music by Cage, Tudor, Mumma, or Behrman; since the sound-systems operated all the time, even the reappearance of a move would lead to a different sound. Teeny Duchamp looked on while Cage and Marcel Duchamp played the game. The evening began with a large audience. Cage and Duchamp adjourned after several hours when the house was empty. Next morning they finished the match; Duchamp had given himself the handicap of a knight, but still beat his pupil.[4]

Revill’s description contains some very misleading statements. There were sound-generating systems prepared by Tudor, Mumma, Behrman and me; no passages of music by Cage were presented to the inputs of the chessboard. I had no affiliation with [Ryerson] Polytechnical Institute; however, the performance was in the theatre on the Ryerson campus. At the time I was a graduate student and Research Associate in the Electronic Music Studios at the University of Toronto. I based my design of the chessboard on photoresistors, not gates or triggering circuits.

Revill also gives the erroneous impression that the event encompassed only one game. In actuality, Teeny Duchamp watched her husband (White) defeat Cage (Black) within a half hour—despite his handicap of only one knight— whereupon Cage (White) and Teeny (Black) played a second game until about 1:00 A.M. in the presence of a waning audience of less than 10 persons, one of whom shouted “Encore!” Duchamp memorized the last moves and positions of the chesspieces in this unfinished game, eventually won by Teeny in New York a few days later. There is no record of the moves in either of the games of Reunion.

The following brief description, by the Duchamp biographer Calvin Tomkins, is close to being accurate, as far as it goes:

Entitled Reunion, the event consisted of Cage and Duchamp (and then Cage and Teeny) playing chess on a board that had been equipped with contact microphones; whenever a piece was moved, it set off a gamut of amplified electronic noises and oscilloscopic images on television screens visible to the audience.[5]

The functions of the chessboard actually depended upon the covering or uncovering of its 64 photoresistors (one per square), not upon the nine contact microphones installed inside. At Cage’s insistence, I provided internal locations for contact microphones so that the audience could hear the physical moves of the pieces on the board if the appropriate conjunctions of inputs, outputs and player movements were (by chance) to occur (Fig. 1). At most, those sounds were soft “thunks,” even when greatly amplified. The oscilloscopic images emanated from my modified monochrome and color television screens, which provided visual monitoring of some of the sound events passing through the chessboard.

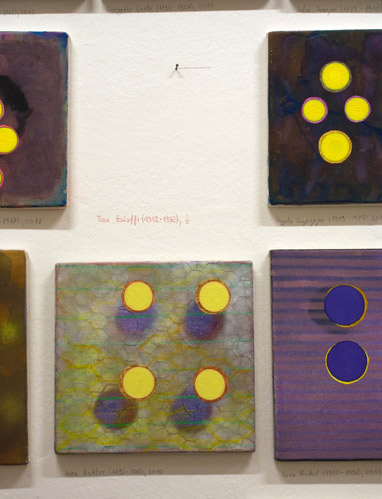

Fig. 1. John Cage installs contact microphones inside the chessboard while David Tudor and Lowell Cross confer. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota)

Preconditions

One cold evening in late January or early February 1968, John Cage telephoned me at the Spadina Road apartment in Toronto where my wife Nora and I lived. He had already heard the results of electronic sound-motion pro- duced by the circuitry of my “Stirrer.”[6] Cage asked if I would build for him an electronic chessboard that would select and spatially distribute sounds around a concert audience as a game unfolded. Because I was in the process of completing my graduate work at the University of Toronto, at first I politely refused his request. He said, “Perhaps you will change your mind if I tell you who my chess partner will be.” After I said “OK,” Cage said, “Marcel Duchamp.”

I was persuaded, of course, and I immediately began to design the chessboard, thesis or no thesis. (Cage figured prominently in my thesis, which explored the historical development of electronic music and the beginnings of electronic music studios between 1948 and 1953.[7])

Cage told me that he was naming the piece Reunion because he wanted to bring together artists with whom he had been affiliated in the past in a homey but theatrical setting. He and Duchamp would play chess at center stage, and the moves of the game would result in the selection of sound sources and their spatial distribution around the audience. Duchamp would sit in a comfortable easy chair (Cage would be content with an ordinary kitchen chair); Teeny would sit close by and watch; my “oscilloscopic” TV sets, on stage, should be in operation; and the chess aficionados at center stage would drink wine and smoke (Duchamp, cigars; Teeny and Cage, cigarettes) (Fig. 2). All the while, Cage’s composer-collaborators Behrman, Mumma, Tudor and I would provide the electronic and electroacoustical sounds of the concert experience. Clearly, Reunion was to be a public celebration of Cage’s delight in living everyday life as an art form.

Fig. 2. During the game, Marcel Duchamp savors his cigar, while Teeny Duchamp and John Cage smoke cigarettes. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota)

Cage left the remaining details up to me but told me to contact the Estonianborn Canadian composer Udo Kasemets, who was organizing a festival called “Sightsoundsystems” in Toronto, for which Reunion was to be the opening event.

Chess had been part of Duchamp’s everyday life for decades, and in the 1960s it became part of Cage’s everyday life, too. The composer had revered Duchamp since their first meeting in 1942, but kept his distance “out of admiration.” Cage eventually found enough courage to ask Duchamp for chess lessons, essentially as a way of getting to know him.[8] The setting for Reunion on the Ryerson Theatre stage—with the imposing chair for Duchamp, the cigars and cigarettes, the wine and chess—was an obvious imitation of the scene at the Duchamps’ second-floor New York townhouse apartment when Cage showed up one or two evenings per week for “lessons.” “The way Marcel taught was to have Teeny and me play chess. . . . ” recalled Cage. “Now and then he would come over and remark that we were playing very badly. There was no real instruction.”[9] In the 1950s, Duchamp was considered by the American grand master Edward Lasker to be one of the top 25 chess masters in the U.S.[10] (see Fig. 3).

|

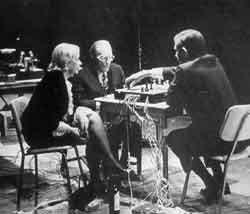

Fig. 4. Teeny Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, just before the first game began. Duchamp had not yet removed his king’s knight. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota) |

The Chessboard

Other than the stipulation about contact microphones and his wish that the chess game would result in the selection and distribution of sounds around an audience, Cage made no requests about the actual operation of the chessboard. However, since I had an understanding of his aesthetic posture in the late 1960s, I made several decisions about the chessboard circuitry that I knew would please him. Immediately before the opening move, “silence” (in the Cageian sense) prevailed (see Fig. 4). The two pairs of ranks on each side, where the chesspieces repose before the game begins, were “off” (i.e. not passing a signal) when their 32 photoresistors were covered; the four center ranks were “off” when those remaining 32 photoresistors were exposed. With 16 inputs (allowing four signals each from the four collaborating composers) and eight outputs (each directed to a loudspeaker system), the complexity of the sound environment enveloping the audience increased as the early part of the game progressed; it then diminished as fewer and fewer pieces were left on the board.

I followed no particular plan while connecting the internal components of the chessboard except to ensure that each of the 16 inputs (designated 1–16) could appear at four of the eight different outputs (designated A–H). For example, during the course of a game, a signal at input 1 could appear at outputs B, E, F and/or G. My arrangement was arbitrary, unplanned and quasi-random, but any of the 16 inputs had a “chance” of appearing in as many as four of the eight loudspeaker locations surrounding the audience. If one assumes that the stage was “north” of the theatre seats, the loudspeakers were arranged as points on a compass: loudspeaker A was northwest; B, north; C, northeast; D, east; E, southeast; F, south; G, southwest; and H, west.

Cage’s hope for sound movement during the game was realized several times during the course of the evening. For example, if Duchamp (White) moved his queen from queen 1 (Q1; input 1, output F) to king’s bishop 3 (KB3; input 1, output B), the sound present in input 1 would move from the loudspeaker at back of the hall (F, south) to the loudspeaker facing the audience, just below center stage (B, north). Ancillary effects of sound choices and motion resulted from the shadows of hands and arms as the players moved pieces; these additional elements pleased Cage immensely.

While Reunion was supposed to provide a homey atmosphere, it was also quite theatrical, with well-defined roles for stars (seated at center stage) and bit players. The use of photoresistors, one imbedded in each of the 64 squares, required that the surface of the board be flooded with bright illumination. The chessboard was in the spotlight, and so were the stars. Cage did not wish to make the lighting requirements an issue, but he did tell me, “I’m so glad that Marcel will be in the spotlight.”

The photoresistors and fixed resistors form a passive resistive matrix. The inputs and the outputs are unbalanced “line level” and can operate with either consumer-grade or professional audio equipment; however, the outputs require a high-impedance load. The purely resistive circuitry attenuates the incoming signals. Accordingly, if a square is “on” (i.e., passing a signal), 12 decibels (dB) gain is required to overcome the attenuation in the two back pairs of ranks, and 24 dB gain is required for the four center ranks.

As seen, each signal is attenuated by a T pad. The two back pairs of ranks have the photoresistors at the input; the four center ranks have the photoresistors connected to ground. In their “off” conditions, the two back pairs of ranks (covered) attenuate incoming signals by an additional 62 dB; the four center ranks (uncovered) attenuate incoming signals by an additional 56 dB. The circuitry does not allow “off” to be completely off, but it was close enough for Reunion.

The purely resistive circuitry of the chessboard adds an insignificant amount of distortion to audio signals, and the frequency response is very uniform. After accounting for its broadband attenuation figures (see above), its response is down no more than 0.3 dB at 20 Hz and 1.3 dB at 20 kHz. The penalty, of course, is the requirement for gain makeup after attenuation.

I built the device with two tournament- size Masonite™ boards, one on top with the photoresistors mounted in the centers of the squares, and the other as the base. (The Reunion chessboard may be turned over for a game of “nonelectronic” chess.) The two Masonite™ boards are separated by ordinary two-byfours painted black. The two-by-four on White’s right-hand side has two openings: one for access to the 24 RCA jacks (16 unbalanced inputs, 8 unbalanced outputs) and the other for the nine cables to the contact microphones mounted inside (see Color Plate A No. 1 and Fig. 5). Its dimensions are 420 ´ 420 ´ 77 mm, or 16.5 inches square by 3 inches high.

Fig. 5. The chessboard partially connected. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota) |

Fig. 6. John Cage makes a move; David Behrman and Gordon Mumma in background. Note bottle of wine at Teeny Duchamp’s feet. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota) |

The Wine

As in the design of the chessboard, Cage left the essential issue of wine entirely up to me. Knowing that Duchamp would defeat Cage handily in a couple of games within about an hour, I decided to buy the stars only one bottle of wine (Fig. 6). This decision was reinforced by the knowledge that I would be paying for it myself and that despite my financial status as graduate student, I would be expected to provide a high quality vintage. The result was a 1964 Château Kirwan,[11] which I had to purchase with a special “license” to serve it in public, from the Head Office of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), on Toronto’s Front Street.

“How many bottles of wine?” asked the LCBO clerk.

“One,” I replied.

“How many people will be in attendance at your event?”

“It’s a public concert, perhaps 500.”

“And you’re buying only one bottle of wine, eh?”

“Yes.”

He wrote this down, and then, with a quizzical shrug, he handed me my copies of the requisite forms and quickly produced a bottle of 1964 Château Kirwan from the large storeroom behind the counter. Nora provided the wine glasses for the evening.

After Duchamp soundly defeated his student-opponent in the first game (despite the handicap), 25 minutes and over one-half of the bottle of wine had been consumed. We still have the glass from which Duchamp drank; the other two and the empty bottle are gone. His glass is now chipped, after our several moves since 1968. If he were alive today, I am sure that Duchamp would comment that the chips only complete the original design.

The First Game

Shortly after the announced time of 8:30 P.M. on Tuesday, 5 March 1968, Reunion began. The collaborating composers “gamely” began producing sounds from their own pre-existent works, all of which utilized special equipment built, or custom-modified, by the individual artists themselves. Behrman’s contribution was Runthrough, Mumma performed his Hornpipe and Swarmer, and Tudor—who did not enter into this engagement with great enthusiasm—was content with the title Reuni on. The works of Behrman, Mumma and Tudor were all examples of “live electronic” music, performed continuously throughout the evening. My sonic contributions were two pieces of pre-recorded tape music, Video II (B)[12] and Musica Instrumentalis, which also produced the oscilloscopic images on the television screens.

As noted above, Duchamp (White) gave his student-opponent Cage (Black) a handicap in this first game, removing his king’s knight from its square (KN1) and replacing it with a U.S. quarter dollar (Fig. 7). With this action, he demonstrated his understanding of the function of the chessboard—and, indeed, his understanding of the entire event. Duchamp played his role as chess master that evening with quiet, unruffled dignity, as though the event was nothing more than that intended: a part of everyday life. As reported above, he decisively trounced Cage within about 25 minutes— the handicap had no bearing on the outcome of that game (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. The Reunion chessboard in 1998, set up with the Duchamp handicap. (Photo: Lowell Cross) |

Fig. 8. Marcel Duchamp takes one of John Cage’s pieces. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota) |

Cage had made a special point of inviting to Reunion Marshall McLuhan of the University of Toronto, then at the height of his fame as a media guru. McLuhan was one of the composer’s favorite “thinkers” of this period, and I was a student in his seminar “Media and Society” during that 1967–1968 academic year. Udo Kasemets later informed me that McLuhan was in the audience, remained for the first game, and left immediately thereafter. I never asked McLuhan about Reunion, and he never mentioned the event to me or to the members of the seminar.

The Second Game

While the star performers exchanged amenities, the break between games provided an intermission—and an opportunity for the exodus of a large segment of the audience. Then, at about 9:15 P.M., the scene reverted to the actual circumstances of the chess “lessons” at the Duchamps’ New York townhouse apartment at 28 West 10th Street: Cage played Teeny, and Duchamp observed (or dozed off; see Fig. 9). The collaborating composers again dutifully provided their electronic signals to the inputs of the chessboard, while the game between Cage and Teeny went on, and on, and on. They were well matched as chess players, and they played seriously and deliberately.

Fig. 9. The second game. Duchamp dozes off; David Behrman in background. (Photo: Shigeko Kubota)

Finally, at 1:00 A.M. on 6 March 1968, Duchamp made known his fatigue. Cage and Teeny agreed to adjourn and to continue the game in the future. The event came to its inconclusive ending.

Interpretation

A large part of Cage’s aesthetic of indeterminacy centered on his wish to remove his personality from his art. He was able to accomplish, and to justify, his indeterminate “system”—and that is what it was, a well-defined system—by utilizing extramusical means to realize his works: the I Ching, pitching pennies to arrive at chance operations, making use of the imperfections on score paper, randomly dropping squiggle-lined transparencies on top of each other, and so on. The idea of using a chess game to realize a musical-theatrical work was one of his most creative: it simultaneously exploited his never-concealed penchants for high theatre, the appeal of chess to intellectualism, and the living of everyday life. If nothing else, John Cage was an intellectual: self-taught, American and as original as they come.

His quest for “purposeful purposelessness or a purposeless play”[13] was elegantly defined in his concept of Reunion, but as a musical performance, the work’s ultimate realization was indeed inconclusive. One game ended too quickly to allow the underlying ideas to be fully experienced by the audience; the other dragged on for so long that it had to be postponed due to the exhaustion of the principals and the dwindling audience. Finally, the circumstances attending Reunion permitted no correlation between Cage’s elegantly proscribed application of his system of indeterminacy and his underlying hope that elegant games of chess could bring forth elegant musical structures. The games clearly were not elegant, and I, for one, held no expectation that they could have brought forth elegant, or even interesting, musical structures. After this inconclusive event, what remained of Reunion? High theatre, Cage’s appeal to intellectualism, and everyday life.

Afterwards

The Toronto newspaper critics were unanimous in their indignation about Reunion, as evinced in the 6 March 1968 afternoon editions of the Star and the now-defunct Telegram. William Littler, music critic for the Star, produced a headline saying the event was “mighty boring.” His colleague and cultural observer Robert Fulford found it “infinitely boring” and an example of “total non-communication, all around.”[14] The Telegram’s Kenneth Winters concluded that the “fusty, dusty, illustrious for reverent immurement in a university.”[15] The editors of the conservative Globe and Mail did not condescend to send a reporter to Reunion.

Two additional performances of the work occurred that spring: one at the Electric Circus in New York, the other at Mills College in Oakland, California. Even though they lived in New York, the Duchamps stayed away from the Electric Circus event; Cage found as his chess partner the editor of The Saturday Evening Post. In addition to setting up the chessboard, I instructed Cage’s friend Jean Rigg in the fine art of margarita-making—in the absence of the Duchamps, no wine was served. A contact microphone was affixed to the Waring Blender, margaritas were served all around as long as there were ingredients, and a grand time was had by all.

At Mills College, I was Cage’s opponent at chess. In keeping with the Cage- Duchamp dress code, I wore a dark suit and tie, but Cage was dressed less formally. The reporter for the Oakland Tribune, Paul Hertelendy, suggested that Cage’s opponent looked like a member of the Mafia, or perhaps an FBI agent, in the incongruous role of chess player. I visitors are just about sufficiently fossilized was White, and I made a very bold opening, a variation on “Fool’s Mate.” Cage commented on my aggressiveness as I took some of his pieces, but that opening is dangerous when facing a practiced opponent, and he went on to win decisively. After all, he had been practicing quite a bit of chess over the past weeks, while I had been endeavoring to end my career as a graduate student.

I did not document either the name of the editor of The Saturday Evening Post or the dates and times of these later performances. By this time, Reunion had become part of my everyday life, and I was content to let it go at that.

The Players

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp was born at home in Blainville, France on 28 July 1887. He was one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century avantgarde art. He died on 2 October 1968 at his apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine (5 rue Parmentier), France.[16]

John Milton Cage, Jr. was born the son of an inventor in Los Angeles on 5 September 1912.[17] He became one of the leaders of the twentieth-century musical avant-garde. Cage died of a massive stroke on 12 August 1992.[18]

Alexina (Teeny) Duchamp was born Alexina Sattler on 20 January 1906 in Cincinnati[19] and married Marcel Duchamp in 1954. She died on 20 December 1995 at her home in Villierssous-grez, France, at the age of 89.[20]

David Eugene Tudor was born in Philadelphia on 20 January 1926. He became one of the premier avant-garde pianists and electronic composers of our time, and began working with Cage as a member of Merce Cunningham and Dance Company (MCDC) in the early 1950s. He took over as the Company’s Musical Director when Cage died. Tudor died in his sleep on 13 August 1996 at his home in Tomkins Cove, NY at the age of 70.[21]

Gordon Mumma was born on 30 March 1935 in Framingham, MA. From 1966 to 1974, he was a composer/musician (with Tudor and Cage) with MCDC and was one of the first composers to utilize electronic circuits of his own design.[22] He is retired from the music faculty at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

David Behrman was born on 16 August 1937 in Salzburg, Austria.[23] He formed the Sonic Arts Union in 1966 with Mumma, Robert Ashley and Alvin Lucier and was a composer/performer with MCDC from 1970 to 1977. He has since taught electronic and computer music at Bard, Mills and other U.S. colleges.

Lowell Merlin Cross was born in Kingsville, TX on 24 June 1938. He has taught in the School of Music at The University of Iowa since 1972.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Juan Maria Solare, an Argentine composer living in Germany, whose many email questions about Reunion prompted me to write this article 30 years after the event. I am also very grateful to Professor Elizabeth Aubrey, musicologist, colleague and dear friend, who patiently read the manuscript and made many helpful suggestions.

(Lowell Cross; Reunion: John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Electronic Music and Chess, Leonardo Music Journal, 1999, Vol. 9, pp. 35–42.)

References and Notes:

[1] Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1996) p. 446.

[2] Nicolas Slonimsky, ed., Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 6th ed. (New York: Schirmer, 1978) p. 267. In the seventh and eighth editions of Baker’s (1984, 1992), with my prompting, Slonimsky corrected the spelling of Duchamp’s name and reported on a singular chessboard, but retained the erroneous statement about a computer and “laser rays.”

[3] Lowell Cross, “The Audio Control of Laser Displays,” db, the Sound Engineering Magazine 15, No. 7, 30–41 (July 1981).

[4] David Revill, The Roaring Silence—John Cage: A Life (New York: Arcade Publishing, Inc., 1992), p. 223.

[5] Tomkins [1], pp. 445–446.

[6] Lowell Cross, “The Stirrer,” Source, music of the avant garde No. 4 (1968) pp. 25–28.

[7] Lowell Cross, “Electronic Music, 1948–1953” Perspectives of New Music 7, No. 1, 32–65 (1968).

[8] See Tomkins [1] pp. 410–411.

[9] See Tomkins [1] p. 411.

[10] See Tomkins [1], p. 289.

[11] The château where this 1964 Margaux was produced, Château Kirwan, was confirmed to me in May 1998 by Mr. Wally Plahutnik, wine merchant for John’s Grocery, Inc. in Iowa City, after he carefully inspected the wine label seen in Shigeko Kubota’s photographs.

[12] The only work heard during Reunion that was released as a recording was my tape music, Video II (B), issued on Source Records No. 5, 1971. The “live electronic” pieces by the other composers were improvised and ephemeral, never to be heard again as they were on that evening. However, the entire event was recorded for possible release by CBS/Columbia (David Behrman, producer); present location and condition of the tapes are unknown.

[13] John Cage, “Experimental Music,” in Silence (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1961) p. 12.

[14] The Toronto Star (6 March 1968).

[15] The Toronto Telegram (6 March 1968).

[16] See Tomkins [1] pp. 18, 449–450.

[17] See Slonimsky [2], 8th ed. (1992) p. 282.

[18] Laura Kuhn, Executive Director of The John Cage Trust, e-mail correspondence to me (3 and 4 December 1998). The Reunion chessboard is part of the collection of The John Cage Trust.

[19] Teeny Duchamp’s birthdate and birthplace were confirmed to me by her children, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier (via fax) and Paul Matisse (via

telephone), on 2 September 1999.

[20] Calvin Tomkins, fax correspondence to me, 20 May 1998.

[21] See the biography section of the David Tudor Pages, hosted by the Electronic Music Foundation web site; accessible at <http://www.emf.org/tudor/ Life/biography.html>.

[22] See the Gordon Mumma page in the on-line artist catalog for Lovely Music, accessible at <http://www.lovely.com/bios/mumma.html>.

[23] David M. Cummings, ed., International Who’s Who in Music and Musicians’ Director y, 15th Ed. (Cambridge, UK: International Biographical Centre, 1996) p. 65.