Ezra Pound as a Confucian Poet

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

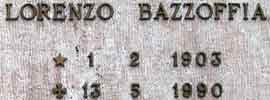

Lorenzo Bazzoffia (1903-1990) |

Lorenzo Bazzoffia (1903-1990) |

Ezra Pound as a Confucian Poet

Angela Palandri

Homage To A Confucian Poet*

'The blossoms of the apricot

blow from the east to the west,

'And I have tried to keep them from falling.'

(Canto XIII)

These last lines from Ezra Pound's first Confucian canto (first published in The Translantic in 1924) may not seem terribly significant to most readers of The Cantos. In fact one of Pound's critics, George Dekker, considers them as "a hang-over from Cathay" with "a faint odour of chinoiserie."[1] To me, however, they are the pivotal lines of the entire Cantos. They are at once a forecast and a summation of the life-long endeavor of an aspiring Confucian poet of our time. Despite the quotation marks, these are really Pound's words issuing forth through the mouth of Confucius. For the pathos is more Poundian than Confucian, even though Pound and Confucius shared the same vision of a human world in harmony with nature, and the same mission, each in his own way and within his own milieu.

Primarily a poet, Pound has engaged in diverse activities throughout his creative life. Thus he has been differently labeled by different people at different times. Achilles Fang of Harvard hailed him as "a Confucian poet," because of Pound's translation of the Shih Ching.[2] But Pound had already been a Confucian poet during the early stages of his literary career, when the Confucian in him subjugated his poetic talent to his mission as a teacher of mankind. To instruct the world he made his poetry a vehicle for this didactic goal. It is of Pound the Confucian poet that I offer my testimony.

My first contact with Pound was in 1952. I was then a foreign student from China still struggling with the English language. 1 could not have dared to study The Cantos, had it not been for a quirk of fate which led me first to correspond with, and later to interview, its author. Early that year I attended a seminar at the University of Washington in Seattle. Sitting next to me was a young man who kept on writing Chinese characters in his notebook. Mistaking him for a student of the Chinese language, I pointed out that some of his ideograms were written incorrectly. He showed me the book from which he was copying. It was The Cantos of Ezra Pound. My initial interest in Pound was aroused primarily by the poet's interest in Chinese.

When research failed to satisfy my curiosity, I decided to write to Pound at St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, D. C. where he was confined, though not at all confident that he would answer me. Imagine my surprise when Pound's first letter dated February 27, arrived. It reads in part:

I will try to answer your questions when you get here in April. I like to get letters but can not do much in the way of reply . . .at any rate I shall hope to see you in April. Visiting hours 2-4 P.M.[3]

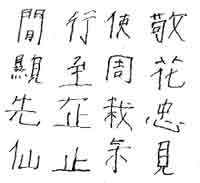

The second letter from Pound was dated March 4. The year 52 was lined out, and next to it was written "or better 4650," which was supposed to be the year of the Chinese calendar according to Pound. Along with this letter was a separate page containing a Chinese quatrain of sixteen ideograms. It read vertically from right to left according to the traditional Chinese system:

Transcribed into the Wade-Giles romanization it sounds as follows:

1. Ching hua Chung chien

2. Shih Chou tsai ts'ai

3. Hsing chih tsài chih

4. Hsien hsien hsien hsien.

The four-character line is typical of the Confucian Odes which Pound had translated. The phrasing is archaic and obscure. Even though the ideograms are still in current use, they have accumulated layers and layers of connotative meanings which add to their ambiguity. It is next to impossible to give a succinct translation. To satisfy the reader's curiosity I offer here a lame line by line prose interpretation:

1. Respect for the kind of intelligence that enables the cherrystone to grow cherries and uphold the cultural florescence with utmost sincerity and perception.

2. Based upon those aforesaid qualities the rulers of the Chou dynasty had cultivated and collected the fruit of their civilization (the Odes?)

3. Governmental and personal actions must proceed and progress to the ultimate goal and come to rest upon perfection;

4. Only then can one enjoy the leisurely life (by watching the moon at one's door), and manifest and glorify the immortality of men (or sennin or sages?) of the past.

In the letter which accompanied the poem Pound wrote:

I have a friend who really knows, and he says my little poem vid. inf. can't possibly mean what he thinks / want it to mean. If you really want to help me you might tell me what you think it means, if it makes sense at all.

Pound was also aware of the unconventionality of using four different ideograms which pronounced the same in one line, for he explained:

The 4th line is a trick line, that I did not expect a Chinese to approve. But it helps me remember the sound belonging to the ideograms—very difficult if one has begun to read by eye only and never been for more than an hour or so with anyone who speaks Chinese.

— AND then people who speak a language are often incapable of either reading or singing a poem.

Without revealing what he wanted the poem to mean, Pound ends his letter by saying: "The other problem would be: how many more ideograms would I have to add to make my meaning clear? if it is possible to get at it." I must have written to Pound after receiving the poem and asked for clarification. Pound's third letter was typewritten. Without date or salutation it begins with "Notes from an anonymous correspondent whose identity Miss Chih-ying Jung may guess at." His comment was:

ideogram INCLUSIVE, sometimes not the least ambiguous but ideogramic mind not always trying to split things into fragments (syntactically etc.) sometimes VERY clear (at others impenetrable, at least to occidental and unskilled reader).

And his explanation was confined to the first line of his poem, beginning

with the second ideogram(hua ![]() ) and ending with the first

ideogram (ching

) and ending with the first

ideogram (ching![]() ):

):

Seems very important to distinguish the merely pictorial ideograms, such as old hua I from the "newer" where the idea of flower (vegetation) is joined with idea of change / metamorphoses continuing in nature /

Meant in first line to drive in the 'respect for kind of intelligence that enables cherry-stone to make cherries' as emphasized in big scrawl preceding translation of Analects.[4]

Then after a paragraph blaming "the powers of darkness" and his publishers for delaying the publication of his Confucian Odes; Pound resumed discussion of his Chinese poem: "To go back to fine one / of the Chinese poem / what I was trying to get across was respect for the changing power in florescence." That was as far as he had gone in the way of explaining what he meant by the poem. (He told me later during one of the interviews that he might use the poem in his Cantos; he has not included it as yet.)

There were two additional letters from Pound before I left for Washington, D.C. Both were very brief. One dated March 24 indicates that Pound did some research on my name. Instead of Miss Jung or my first name in Chinese, he addressed me as "Honorable — Glory — Produces — Wheatear,"[5] an ideogrammic reading of my first name (Chih-ying) and a literal translation of my last name, but I did not know the extent of his research until the time when he introduced me to T. S. Eliot.

During my four months in Washington, D.C., I visited Pound regularly once a week, with only a few exceptions. Of the series of visits I had, two stand out in my memory: my first visit to St. Elizabeths Hospital, and my meeting with T. S. Eliot there.

II

Upon arriving in the capital I wrote to Pound. I was given an appointment on the following Saturday. Despite my eagerness to meet the poet, I became increasingly apprehensive as the designated time approached. Perhaps I was uncertain of Pound's mental condition, or perhaps I was worried that once he discovered my ignorance he might refuse to grant me an interview. Nevertheless I went in the pouring rain. After I signed the visitors' register in the central building, I was ushered to another building by a man in a white coat. He unlocked a heavy metal door which opened to a flight of stairs leading to another door on the second floor. After letting me in through the second door, he shouted into the dark corridor above the clamor of insane sounds of laughter and groanings: "Mr. Pound, you have another visitor," and was gone, locking the door behind him. Before I took in all the strange surroundings, a man I recognized to be Pound strode toward me and led me to an alcove where he and three other people were sitting. "I usually receive guests outside in the open air, except for rainy days like this," he said as he introduced me to the other visitors. Sitting in the middle with her back against the window was Olga Rudge, who had just arrived from Siena the previous week. To her left was a young man with a British or Australian accent, whose name I did not catch. The other was Professor Giovanni Giovannini of the Catholic University of America.

Pound made three trips to his cell next to the alcove. First he brought a chair for me and then he brought two armsful of books. Among them were the Square $ Series of the Analects and Fenollosa's essay, his Money Pamphlets, the bilingual edition of Cavalcanti's Rima and the Stone Classic edition of his translation of Confucius interleafed with Chinese texts.

"The only way to learn the literature of a foreign language is to have the original text with the translation," he explained. "The American people are too lazy to be bothered with other languages, but they will, if well guided." There was a pirated, bilingual edition of James Legge's translation of the Four Books of Confucius, dog-eared and its spine held together with band aids and scotch tape. The margins inside were covered with notes or comments, evidently Pound's own.

"This little book has been my bible for years," remarked Pound, "the only thing I could hang onto during those hellish days at Pisa. . . Had it not been for this book, from which I drew my strength, I would really have gone insane . . . so you see how I am indebted to Kung."

"Read it constantly," he admonished, "if you have grasped the import of this volume, nothing can really hurt you or corrupt you—not even American civilization, or rather, uncivilization." And he gave me an intent look as if to measure the depth of my knowledge, or ignorance, I had to confess that like most modern Chinese my knowledge of Confucius was superficial and that my purpose in studying in America was not to advocate Confucianism but to transmit the best of the Occident to my own people.

"If you wish to promote occidental culture in China, give your people that which is essential of the Western tradition, the real stuff instead of the husks they feed you at the universities. Give them Aeschylus, Homer, Dante—study from the list I emphasized in A B C of Reading and 'As Sextant', the postscript to Guide to Kulchur." He left us again, and when he returned he handed me a typewritten list which reads:

Addition to "As Sextant"

Golding's translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses I

as "Strange Tales from Chinese Studio" read for

pleasure, not as basic education.

American prose: Adams—Jefferson Letters

J. Adams—Waterhouse Letters

L. Agassiz / naturalist I tradition straight from Mencius

Economic Historian: Alex Del Mar

To rectify earlier criticism / more emphasis on Sophocles.

contrast the Trachiniai with Electra and Antigone /

Trachiniai with the Noh.

As yet no adequate knowledge here of Chinese classical plays.

The above list, with its particular reference to Chinese works, was perhaps prepared specifically for me, since I have never seen it in print anywhere.

"One must know these to form a basis of thinking," he emphasized, "and then branch out to whatever type of literature he prefers. The American universities force their students to swallow rubbish instead of giving them nutriment . . . Have you heard of the Hundred Great Books Program started at St. John's University?" Someone answered in the affirmative.

"Well, not that the selection is entirely bad," he admitted, "but why give the students two barrels of sawdust along with half a bunch of grapes?"

For a while the young man with the British accent engaged Pound's attention, and the conversation drifted from literature to economics- -areas with which I was unfamiliar. Also I could not hear very well, as the commotion and the blare of the TV at the end of the hall became louder with the showing of a western movie.

At last I mentioned his Chinese quatrain.

"Oh, that little Chinese poem of mine which you did not understand. Well, if I wrote it in English it would probably fill a book. That is why I used the ideograms; each of them could embody what one must say in a hundred lines. Besides, I like the sound. When the words are put together they sing by themselves." I reminded him that he had written in 1940 that "the great part of Chinese sound is (of) no use at all. We don't hear parts of it, and much of the rest is a hiss or a mumble."[6] To this he replied: "If I did, I don't remember. At any rate ones opinions change as one progresses. . . He should not be held responsible for what he said or wrote decades earlier. I have never heard how Chinese poetry should be read, but Hike to play with it my own way." Without being urged, he began to chant his Chinese verse in the old fashioned sing-song manner I had been taught as a child. He drummed his fingers on his knee to mark the duration and stress of each syllable, with a long caesura falling in the middle of each line akin to the meter of the Seafarer. When he was through, Miss Rudge led the applause. "Occidentals have a lot to learn from the Chinese—the ideogrammic method as well as the metrics," observed Pound, "the Chinese tones are very musical. They make you sing. That's the way poetry should be in any language. The Reverend Eliot does not sing, the old Doc Billy (Williams) does not sing. . .they have lost the art. . ." Then after a pause, "But it will come back . . .Yeats wanted to see all his poems set to music, as Kung set the Odes to music."

At the end of the visiting hour Pound told me to return the following Saturday.

III

My visits thereafter were less exciting but more pleasant. For most of this time Pound was holding audience on the lawn under the shade of a huge elm tree (or was it a walnut?) Olga Rudge had gone back to Europe; Dorothy Pound had returned to her husband's side after a two-week vacation. My visiting hour was usually shared with a young couple, Gloria French (of whom Pound had written to me earlier) and her husband, both budding poets. After a couple more visits, we settled down to a pleasant routine. We were to read during the week, at our own speed and choice, works by, or suggested by, Pound, and bring up any subject there from on which we wished Pound to expound. Then he would read to us a few pages from The Cantos. We could ask questions on things that we did not understand in the poem. I refrained from asking, not because I understood everything, but because it would destroy the magic moment when the dullest passages turned to music and the dross turned to gold. And I was annoyed whenever others interrupted his reading with questions.

Once I brought Pound some Chinese pastries. And Pound asked jokingly, "Is that the shu hsiu for my teaching?" When I failed to grasp what he said, he picked up a piece of paper and drew the two Chinese characters. I was impressed. For the term shu hsiu ![]() came from the Chou Li (Book of Rites) meaning "dried meat." Confucius' poorer disciples used to bring him dried meat as tuition. My only regret is that I was too poor even to bring my shu hsiu to Pound frequently.

came from the Chou Li (Book of Rites) meaning "dried meat." Confucius' poorer disciples used to bring him dried meat as tuition. My only regret is that I was too poor even to bring my shu hsiu to Pound frequently.

The most important event for Pound, and for me, that summer, was T. S. Eliot's visit on June 21. Pound had talked about it for weeks prior to the awaited date, and told his visitors to stay away on that particular day. Then one day he asked me if I would like to meet Eliot. Would I indeed! "In that case you shall come, not at the regular time, but after three, so that I can have an hour with Possum alone." Mrs. Pound explained that the two needed the time to themselves "to squabble."

That Saturday I arrived at St. Elizabeths shortly after three as I was told, but Pound was not at his regular place on the lawn. When I reported to the office, I was told that Pound had left word not to admit visitors that day. "But I have his permission to come," I protested. The man inside the counter examined his memo pad and said, "They are inside the tennis courts." The tennis courts were to the left of the building; a thick hedge screened them from view. Pound, in his usual T-shirt and khaki cut-offs, was reclining on his folding canvas chair. Opposite him on a long bench sat Eliot in a dark suit and a dark tie. Mrs. Pound was absent.

"So you found us in our hideout," Called out Pound, "Mr. Eliot fears publicity and the public. That's what happens when one is too much in the limelight." Turning to Eliot he said, "This is Wheatear from China, her ancestor's tablet is in the Temple of Confucius." I did not know what to make of the last remark. Was he making fun of me? (Imagine my surprise when years later, on Taiwan, in the Confucian temple of Tainan, I discovered among the seventy-two tablets of Confucius' disciples one bearing the name of .Tung Ch'i. That particular ideogram, Jung ![]() , a rare surname, happens to be mine also.

, a rare surname, happens to be mine also.

To hide my embarrassment I quickly explained that "Wheatear" is not my real name, but Pound's interpretation of last ideogram of my name. Eliot stood up to shake hands, asked me to say my name in Chinese. "Jung Chih-ying," he repeated slowly, "that does have the auditory quality of the wheatear." At this Pound burst out laughing, to my great confusion. For Eliot, not knowing the ideograms, had transformed me from a grain bearing plant into a chirping bird.

"We were just reminiscing about our London days," said Pound recovering from his laughter. Turning to Eliot he resumed their conversation as if they were alone, "To think that you called that warmonger Rupert Brooke the best of Georgians!" "Well, the word Georgian should have been sufficient to qualify my statement. After all, what does the best of Georgian amount to?" retorted Eliot, "but you even wrote an introduction to Lionel Johnson's book!" I forgot what Pound's answer was, but the repartee continued for quite a while until Pound turned to me and said: "If you have any questions to ask Mr. Eliot, here is your chance. After all, it isn't every day that you meet such an eminent personality."

I had prepared carefully a list of questions beforehand but in my haste had forgotten to bring it. So I began to ask whatever question came to mind. Some of them were very naive. A part of the conversation that I recall went like this (I use Wheatear to stand for myself here):

Wheatear: "Did you come to the States mainly to see Mr. Pound?"

Eliot: "I came to Washington mainly to see Mr. Pound."

Pound: "Oh, he pops in and out of New York without letting me know; but I always know."

Wheatear: "Are you still working in the Lloyds Bank in London as you did years ago?"

Eliot: "The only connection I have with any bank is in the transactions of insignificant sums of currency."

Wheatear: "What are your current literary activities? I mean, are you writing more long poems like the Four Quartets? or plays like The Cocktail Party?"

Eliot: "Hush, Mr. Pound does not approve of my literary activities. Unlike him I am not an epic poet, I am in a sense an entertainer. .my main interest has been the stage . . . drama is my medium. It seems to reach more people. . ."

Pound: "He deals out sugar-coated pills."

Wheatear: "I know you are Anglo-Catholic and your poetry stems from a deep conviction of Christian philosophy. But some of your critics claim that there are traces of Buddhist influence. Could there be Taoist influence as well?"

Pound: "Aha, I knew there was something wrong with him—he has been consorting with Taozers and Föezers!" (These are Pound's coined terms for Taoists and Buddhists, Fö being the Chinese word for Buddha.)

Eliot: "If there is such influence, at least I am not aware of it.

Wheatear: "What about such lines as 'Teach us to care and not to care/Teach us to sit still" (Ash-Wednesday), or "In my beginning is my end," and "In my end is my beginning" (Four Quartets)? I also find something akin to the Taoist paradox in "and what you do not know is the only thing you know; / And what you own is what you do not own / And where you are is where you are not."

Eliot: "A very interesting observation. But there was no conscious effort on my part. What I attempted to get at is the universal truth . . .In the final analysis all religions point to the ultimate truth."

Pound: "Kung was concerned with the truth of here and now."

Eliot (smiling): "We can't quarrel with him on that, can we?" (I still wonder whether the "we" included me also, or was an editorial "we.")

It was nearly 4 P.M. Before departing, Eliot extended me a verbal invitation to visit him if I ever got to London. And Pound rejoined: "But you will never pass by his seven secretaries." Nevertheless, Eliot wrote my name in his small address book. Meanwhile Pound got to his feet, one hand holding his folding chair and the other extended to Eliot. It was a moving sight to see Eliot hold Pound's hand in his own, his head bent low as if paying homage. "His humility is endless," I thought to myself as I walked with Eliot toward the gate in silence. Outside the gate we said goodbye. He headed for the nearby apartment of Dorothy Pound, who was waiting for him. I went to my bus stop, feeling grateful to Pound for giving me the opportunity to meet another great poet of our time.

IV

Everything was anticlimatic after Eliot's visit. Pound became more preoccupied and less communicative. The humid summer heat had perhaps affected everyone's mood. A couple of times when expected callers did not show up, Pound was visibly irritated.

Toward the end of July I received a letter from my advisor, Professor Jackson Mathews, from the University of Washington. He had obtained permission from Harvard University Press for me to see the manuscript of Pound's Confucian Odes if I could go to Cambridge. Before I left town I phoned Mrs. Pound, explaining the reason for my absence.

It was closing time when I reached the offices of the Harvard University Press. The director, Mr. Wilson, was out of town, but he had instructed his secretary that I be allowed to use his office in which to read Pound's manuscript. I arranged to begin on the following day. When I arrived at Mr. Wilson's office the next morning, his secretary met me at the door. "I am afraid I have some bad news for you, this came last night." And she handed me a telegram. It was from Pound addressed to Achilles Fang: "Manuscript is not for inspection of traveling student." The author's wishes must be respected, I was told. I went to see Achilles Fang for help. He was apologetic, but laid the blame on me for letting Mrs. Pound know the purpose of my trip.

Frustrated, I stayed away from St. Elizabeths for two weeks, trying to cool off. Even though I knew Pound had every right to stop me from reading his manuscript, I could not understand why he should go out of his way to thwart my efforts, especially since he had been kindness itself all along. When I finally went to see Pound, I was still disgruntled. Pound showed no obvious displeasure at my action, but made no apology for his. When I pressed him for an explanation, he said simply: "There is enough material for a dozen theses on me. Why must you probe into an unpublished work'? There will be sufficient time for that later. At any rate, all you are required to do for a thesis is to rehash what others have said about a certain author or his works. Originality is not encouraged. You'll only confuse your professors by covering untrodden ground. Most professors wouldn't want to extend their thinking beyond the categories already set up for them."

A week later when I went back to St. Elizabeths for the last time to say goodbye, Pound handed me two yellow sheets, full of pointers, suggestions and references which were of great help to me on my dissertation.

On the train moving westward I had plenty of time to assess the outcome of my Washington, D.C. venture. Although I was unable to see Pound's version of the Confucian Odes and the Fenollosa notebooks which accounted for his Cathay, I had attained most of the objectives I originally set out. From Pound's sporadic reminiscences I gathered that his interest in China predated his acquisition of the Fenollosa manuscripts ("Fenollosa's work was given me when I was ready for it. It saved a great deal of time. . ."):[7] His original acquaintance with Confucius was through German and French authors, who in turn received their knowledge from the early Jesuits in China. Through conversation and observation, I was able to make a fair evaluation of Pound's knowledge of Chinese, which had been either over- or under-estimated by his critics. But most of all, I had, during those few months, undergone an intensive period of schooling under the guidance of a vigorous and dedicated teacher of the Confucian strain. Pound did not teach me how to write, but he taught me what and how to read. Moreover, he led me back to the Confucian precepts which have fallen into disuse in present-day China.

I knew that Pound was misunderstood by many people and mistreated by his own government, but it took a decade of the Vietnam War for me to realize that Pound was penalized not because of his so-called profascist propaganda but because of his insistence on cheng ming, a Confucian precept meaning to use exact words or to call things by their correct names, which no government could afford to do without losing its credibility.

* Angela Palandri; Homage to a Confucian poet, Paideuma, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 301-311, Winter 1974.

Notes:

[1] Sailing After Knowledge: the Cantos of Ezra Pound. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963), p. 29. Apparently Dekker, in his source-hunting for Canto XIII, did not go beyond the confines of the Four Books of Confucius and Mencius. Had he looked further he might have discovered that the introductory and the concluding lines of this canto have their origin in the Chuang Tzu, which makes reference to the places frequented by Confucius and his disciples. The apricot orchard was believed to be the place where Kong gave lectures. Its actual site, marked by a pavilion enclosing a stone slab with the seal characters of Hsing Tan ("Apricot Temple"), is in front of the Confucian Temple in present day Ch'iu-fu of Shantung, Confucius' home town. Through which particular source Pound acquired his information is not known. Far from being chinoiserie, the "blossoms of apricot" symbolize at once cultural florescence arm Confucian teachings.

[2] Ezra Pound, The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954), p. xiii.

[3] The Chinese Ode and previously unpublished letters or writings of Ezra Pound in the article by Angela Palandri and the article by Deba P. Patnaik are copyright ©, 1975, by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. The characters are drawn by the managing editor. CFT.

[4] Beginning of sentences in Pound's letters are in 1. c.

[5] "Wheatear" is derived from the compound ideogram ![]() , which has the picture of a wheat stalk and the picture of a head.

, which has the picture of a wheat stalk and the picture of a head.

[6] D. D. Paige, ed. Letters of Ezra Pound (New York, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1950), p. 347.

[7] Ezra Pound, Make It New (London: Faber & Faber, 1934), p. 8.