Olga Rudge and Ezra Pound in Paris

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 3 4 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

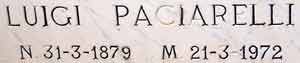

Luigi Paciarelli (1879-1972) |

Luigi Paciarelli (1879-1972) |

Olga Rudge and Ezra Pound in Paris

Anne Conover

Olga and Ezra in Paris (1922–1923)*

‘‘Where everything in my life happened’’

Olga Rudge had nothing to gain by an alliance with Ezra Pound. Her reputation as a concert violinist was firmly established, her social position secure. She was living in her late mother’s tastefully furnished flat near the Bois de Boulogne on the fashionable Right Bank; her only contact with the bohemian side of the Seine was the atelier of the Grande Chaumiere, where her brother Teddy had studied landscape painting before the Great War. As Olga remembered the Americans on the Left Bank: ‘‘they stayed to themselves;[1] they did not know the French as we did.’’

Ezra Pound was Left Bank. When he met Olga in the fall of 1922 he was undertaking a translation of Remy de Gourmont’s Physique de l’Amour for the American publisher Boni & Liveright. Gourmont’s theory that ‘‘civilized man endures monogamy only when he can leave it and return at will’’ was shared by the poet. He was also exploring the connection between creativity and sexuality, and in the translator’s preface he suggested ‘‘there must be some correlation[2] between complete and profound copulation and cerebral development. . . . The brain itself . . . is a sort of great clot of genital fluid held in suspense.’’ The woman’s role was to be the passive receptacle for man’s sperm; a secondary role in the creative process, but an essential one nonetheless. But not just any woman would serve as the receptacle for this poet’s creativity; only an artistic and accomplished woman would do for a permanent liaison, and the high-spirited Olga was an obvious choice—a striking, poised young artist with dark hair bobbed and parted in the middle in the high fashion of the Twenties. Meeting her for the first time, one could not forget her fiercely energetic way of talking and moving about—an ‘‘Irish adrenal personality,’’[3] as one friend described it—that drew into her circle handsome and talented people.

She was wearing a jacket in her preferred shade of red embroidered with gold Chinese dragons the night she met Ezra. Another of Pound’s enthusiasms was translating the works of Li Po, a task left unfinished by the late Orientalist Ernest Fenollosa, and the oriental-motif jacket[4] established a point of communication. Olga had inherited the jacket from Judith Gautier, daughter of the esteemed writer and translator of Chinese poetry, Theophile, whose apartment she visited as a child with her mother. There was instant attraction between the poet and the young musician with the violet, or periwinkle blue, eyes he would describe in The Cantos as the eyes of Botticelli’s Venus. But he left the fete with Mademoiselle Raymonde Collignon, a blonde singer of ballades, and soon thereafter departed for the South of France with his wife, Dorothy.

Olga Rudge in Paris

‘‘Paris is where Ezra Pound and Olga Rudge met, and everything in my life happened,’’ Olga said later of the chance encounter with Ezra at 20, rue Jacob, in the salon of Natalie Barney. Like Olga, Barney had arrived in the City of Light as the child of an expatriate artist. Her historic townhouse near the boulevard Saint Germain was a refuge for escapees from Puritan mores, and her explicitly lesbian novel, Idylle Saphique, contributed to the legend of ‘‘the wild girl from Cincinnati.’’[5] In her youth, Barney wore white flowing gowns by Schiaparelli or Lanvin and presided like a goddess under the domed, stained-glass ceiling of her drawing room—a rich blend of Turkish hassocks, lavish fur throws, tapestries, portraits, and vast mirrors— described by one guest as ‘‘hovering between a chapel and a bordello.’’[6]

The grand piano that Wanda Landowska played in an earlier era premiered the contemporary works of Darius Milhaud and George Antheil in the Twenties. The large hexagonal table in the dining room was always spread with a feast prepared by Madame Berthe, the housekeeper, confidante, and amanuensis known for her chocolate cake, harlequin-colored gateaux, and triangular sandwiches ‘‘folded up like damp handkerchiefs.’’ The Duchesse de Clermont-Tonnerre, a grande dame of impeccable lineage, presided over the tea service, though port, gin, and whiskey were more popular with American guests. A green half-light from the garden reflected from the glasses and silver tea urn as from under water. The garden was an unkempt miniature forest, with rambling paths and iron chairs balanced precariously near a marble fountain long choked with weeds and the Temple a l’Amitie, a copy of the Temple of the Vestal Virgins in Rome.

Barney, some twenty years Olga’s senior, was the leader of a freedom-loving and bohemian group of intellectual women in the early 1900s: Colette, Anna de Noailles, and the spy Mata Hari. Another generation, Olga’s contemporaries, succeeded them: English suffragettes, militant feminists and lesbians, tolerant heterosexuals and asexual androgynes. The expatriate American painter Romaine Brooks and the Princesse de Polignac (née Winaretta Singer, heiress to the sewing-machine fortune) were among the favored inner circle.

Musical reputations were established at Barney’s salon, and Renata Borgatti, Olga’s accompanist, invited her there after the two women returned from a sun-filled vacation on the Isle of Capri. Olga recognized Ezra, the tall American wearing a signature brown velvet jacket, as someone she had seen at a concert in London the year before. He was the last to leave, and she had asked Renata, ‘‘Who is that?[7] He looks like an artist.’’

In an early photograph, Pound appears in front of Hilaire Hiler’s Jockey Club wearing the floppy beret, velvet jacket, and flowing tie of artists of an earlier generation. With him are Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, and the notorious Kiki of Montparnasse. Those who knew Ezra in the prime of life testify that photos did not do justice to his charismatic appeal. Margaret Anderson, founder of the Little Review, described the poet’s robustness,[8] his height, his high color, the mane of wavy red-blond hair. And the eyes: ‘‘Cadmium? amber?[9] no, topaz in Chateau Yquem,’’ another of his contemporaries observed.

Anderson remarked that Pound was then somewhat patriarchal in his attitude toward women. If he liked them, he kissed them on the forehead or drew them up on his knee. But there was about Ezra an air of someone confidently living his life in high gear. It was not entirely in jest that he wrote to Francis Picabia in the summer of 1921 that he had been in Paris for three months ‘‘without finding a congenial mistress.’’[10]

Pound and his British wife, Dorothy Shakespear, had crossed the Channel in January 1921 and settled into a pavillon at 70 bis, rue Notre Dame des Champs, a first-floor apartment facing an alleyway, the bedrooms above reached by an open stairway. There was a tiny lean-to kitchen, of little interest to Dorothy (in Canto 81, Ezra would write ‘‘some cook, some do not cook’’). As he described his digs to the wealthy art patron John Quinn: ‘‘The rent is much cheaper[11] than the hotel . . . 300 francs a month [about twelve dollars in 1921] . . . and I have built all the furniture except the bed and the stove ’’ (sturdy wood and canvas-back chairs, and a triangular typing table that fit neatly into one corner). The books, manuscripts, and a Dolmetsch clavichord were brought over later from London, and Pound added a Henri Gaudier-Brzeska sculpture and the canvas by Japanese artist Tami Koume that covered one wall.

At age thirty-six, Ezra still lived on small stipends from reviews and other literary endeavors, supplemented by Dorothy’s allowance and contributions from the elder Pounds in Philadelphia. Since the time of Victor Hugo, Notre Dame des Champs, close by the Luxembourg Gardens and the charcuteries and bakeries of the rue Vavin, has been home to improvident writers and artists. Ernest Hemingway, who lived with his wife Hadley above the sawmill at No. 13, wrote that Ezra’s studio was ‘‘as poor as Gertrude Stein’s[12] [on the neighboring rue de Fleurus] was rich.’’ Ezra was not a welcome guest on the rue de Fleurus; during his first audience with Stein, he sat down too heavily on one of her fragile chairs, causing it to collapse. Stein did not find Pound amusing:[13] ‘‘he is a village explainer,’’ she famously said, ‘‘excellent if you were a village, but if you were not, not.’’

Pound ignored the Stein circle and joined forces with Barney, another fierce individualist. He had corresponded with Natalie as early as 1913 about the translation of de Gourmont’s Lettres a l’Amazone, open letters to Barney then appearing in the Mercure de France, the sensation of Paris. When Ezra arrived on the scene, Natalie provided introductions to Anatole France, Andre Gide, Paul Valery, the distinguished literati of an older generation, and his contemporaries, the Dadaist painter Francis Picabia and the avant-garde poet Jean Cocteau, whom Pound described as ‘‘the best poet and prose writer in Paris.’’ With such comrades, Ezra often was observed enjoying Parisian nightlife with women other than his reserved wife, whose porcelain skin and ice-blue eyes were, in Pound’s words, ‘‘a beautiful picture[14] that never came to life.’’ It was Ezra’s custom to drop in at odd hours, often midnight, at bistros on the rue du Lappe or the Deux Magots, the Dome, and other Left Bank cafes where artists and intellectuals gathered.

One of the first friends Ezra called on in Paris was composer and musician Walter Morse Rummel. The son of a German pianist and a daughter of Samuel F. B. Morse, the telegrapher, Rummel crossed over from London to cut a dashing figure in the Parisian music world. Rummel discovered and set to music Provencal poetry, also an enthusiasm of Ezra’s. And it was Rummel who introduced the poet to Raymonde Collignon, a young soprano known for her porcelain figure and sleek head set in a basketwork of braids.[15] Wearing a shimmery gold-yellow frock, Raymonde arrived at Barney’s Turkish drawing room on Ezra’s arm the night that he met Olga.

At their next meeting,[16] Olga recalled that Barney was receiving a select group of friends in her boudoir, and Ezra was acting as cavaliere servente to the Marchesa Luisa Casati. (Romaine Brooks’s thinly disguised painting of Casati rising nude from the rocks at Capri filled one wall of Barney’s bedroom.) Ernest Walsh, the poet and co-editor with Ethel Moorhead of This Quarter, later husband to the novelist Kay Boyle, was among the chosen few that evening. As they were leaving, Ezra suggested to Olga that she invite Walsh, another visiting American, to her apartment to give him an insider’s glimpse of the Right Bank.

Ezra had not yet visited the rue Chamfort, and when he came, Olga assumed he would be accompanied by Walsh. But when she next saw him Ezra was at her door, alone, holding the score of an opera he had written, Le Testament de Villon.

Paris was alive with the new music—Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, Virgil Thomson, Erik Satie, Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud. Ezra, who was already experimenting with new rhythms in poetry, surprised visitors who came[17] unannounced to 70 bis, rue Notre Dame des Champs, in the throes of composing an opera with the assistance of Agnes Bedford, an English pianist and voice coach, on the notation.

Pound’s study of music had begun on his mother’s piano in Wyncote, Pennsylvania. In 1907, he became enamored with the French troubadours and the works of Francois Villon, the fifteenth-century vagabond poet, an interest reinforced by long walking tours in Provence. ‘‘He sang it [Le Testament] to me, with one finger on the piano,’’ Olga remembered. ‘‘I discovered the pitch was noted accurately, but not the time. We started to work correcting the time.’’ Looking over Ezra’s shoulder, Olga interrupted his ‘‘piano whack’’ to protest that the poet was not playing the written score. But Pound, the creative genius, was not easily instructed; he continued to play the music he heard with his inner ear, not the notes on the page before him.

The Rudge–Pound correspondence began on June 21, 1923, with a brief pneumatique between the Right and Left Bank. These messages on blue paper transmitted through underground tubes from one post office to another and hand delivered by messengers on bicycles were then the most rapid means of communication. This one was the first of many short notes to make or break appointments: ‘‘Me scusi tanto,[18] ma impossible per oggi . . . domani forse da Miss B[arney]?’’ They were often written in Italian and closed with the pet name he often used for Olga, ‘‘una bella figliuola’’ [beautiful young girl].

Ezra soon introduced Olga to Margaret Anderson’s protégé, George Antheil, a young pianist and composer from New Jersey who had arrived in Paris to attend the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s Les Noces on June 13. With his Romanian belle amie Böski Marcus, he took rooms above Sylvia Beach’s landmark Left Bank bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. Short and slight, with clipped blond bangs that made him look even younger than his twenty-three years, Antheil met avant-garde composer Erik Satie and ‘‘that Mephistophelian red-bearded gent, Ezra Pound,’’ at a tea honoring Anderson and the actress Georgette Leblanc.

Ezra began to take Antheil to Olga’s flat to practice. Olga suggested Pound’s initial interest in her was her mother’s piano—for Ezra, she insisted, work came first. Antheil soon set to composing a violin sonata for Olga, determined to make the music, he wrote Ezra, ‘‘as wildly strange[19] as she looked, tailored to her special appearance and technique. It is wild, the fiddle of the Tziganes . . . totally new to written music . . . barbaric, but I think Olga will like it . . . it gives her more to do and show off with than the other sonatas.’’

In late summer, while Dorothy was in London to assist her mother, Olivia Shakespear, in caring for her husband during a long illness, Ezra introduced Olga to the land of the troubadours. No written record remains of that summer holiday, or their itinerary, only a fading black-and-white photograph album labeled ‘‘August 1923—Dordogne.’’ Olga was the photographer and Ezra often the subject, appearing under gargoyles of the cathedrals in Ussel and Ventadour and other unidentifiable French villages. In her eighties, she reminisced about ‘‘the photos Ezra Pound and I took on our walking tour. . . . ‘I sailed never with Cadmus,’ ’’ she recalled, referring to a line in Canto 27, ‘‘but he took me to Ventadour.’’ On the back of one snapshot she wrote: ‘‘note how elegant[20] a gentleman could be, walking 25 kilometers a day with a rucksack—in those days, no hitchhiking.’’

The Antheil-Rudge collaboration at Olga’s flat continued on an almost daily schedule in the fall. Antheil praised Olga’s mastery of the violin: ‘‘I noticed when we commenced[21] playing a Mozart sonata . . . [she] was a consummate violinist. . . . I have heard none with the superb lower register of the D and G strings that was Olga’s exclusively.’’ On October 4 at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees, the three short Antheil sonatas that premiered as the curtain raiser for opening night of the Ballets Suedois became the most controversial musical event of the season. A correspondent of the New York Herald compared the evening to the premiere of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps: ‘‘a riot[22] of enormous dimensions occurred when George Antheil . . . played several piano compositions. . . . Antheil is a new force in music . . . of a sharper and more breath-taking order than Stravinsky.’’ In his autobiography, Antheil recalled:

My piano was wheeled out[23] . . . before the huge [Fernand] Leger cubist curtain, and I commenced playing. . . . Rioting broke out almost immediately. I remember Man Ray punching somebody in the nose in the front row, Marcel Duchamp arguing loudly with somebody in the second. . . . By this time, people in the galleries were pulling up the seats and dropping them down into the orchestra; the police entered and arrested the Surrealists who, liking the music, were punching everybody who objected. . . . Paris hadn’t had such a good time since the premiere of . . . Sacre du Printemps.

The riot was used later as a film sequence in L’Inhumaine, starring Georgette Leblanc.

Pound was then undertaking a transcription of a twelfth-century air by Gaucelm Faidet that he had discovered in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, ‘‘Plainte pour la mort du Richard Coeur de Lion,’’ and composing an original work, Sujet pour Violon, for Olga’s concert on December 11 at the ancien Salle du Conservatoire. One critic of that concert praised the young violinist as possessing ‘‘a very pretty sonority[24] bidding fair to develop into virtuosity . . . We admire this young artist for having enough courage to sacrifice on the altars of Mr. Antheil’s conceited art, personal honors which otherwise might have been hers. Both her enterprise and her playing merit commendation.’’ Pound’s pieces won their share of applause: ‘‘to those who like to push their musical researches into that kind of thing [they] were extremely interesting.’’

But the critics’ focus in the December concert was on the controversial Antheil sonatas for violin and piano. The Paris Tribune: ‘‘Can this really be denoted music?[25] . . . No, it is a kind of primitive melopoeia . . . like those bizarre tambourine accompaniments of Arab or Moroccan musicians when in their drinking dens and cafes.’’ Mozart’s Concerto in A Major was called a ‘‘a heaven-sent beneficent repose for the ears’’ by one critic, while another dissented: ‘‘In his own music, Mr. Antheil may try to ‘get away’ with whatever he wants to, but he really should beware of composers so refined and subtle as Mozart.’’

Ezra advised Olga to ‘‘practice the Mozart[26] and Bach for a couple of days by themselves. I mean don’t play the Antheil at all, but concentrate on B[eethoven] and M[ozart], so as to EEEliminate the effects of modern music.’’

In late December, Ezra checked into the American Hospital in Neuilly with an appendicitis attack. After a discreet visit to the hospital with flowers (one of which she pressed and saved with a card from Charlot, the florist), Olga wrote: ‘‘Dolcezza mia,[27] how happy she was to see him . . . la bonne tete . . . les mains . . . maigre, bianchi—bella soi!’’ In old age, Olga confided that the young Ezra possessed the most beautiful head, the most expressive hands she had ever seen. Her letter reveals a greater degree of intimacy: ‘‘be good and lie on your back and don’t let the pack slip off that tummy peloso.’’

Whatever Ezra’s complex motivations, soon after the new year of 1924 began he and Dorothy left Paris for Rapallo, a quiet resort on the Riviera di Levante of Italy.

* Anne Conover; Olga Rudge and Ezra Pound, Yale University Press,

New Haven & London, 2001, pp. 1-9.

Notes:

[1] ‘‘They stayed to themselves’’: Olga Rudge, taped interview with P. D. Scott, Berkeley, Calif., 12 Oct 1985.

[2] ‘‘civilized man’’; ‘‘some correlation’’: Gourmont, Natural Philosophy, tr. Ezra Pound, 295.

[3] ‘‘Irish adrenal personality’’: Antheil, Bad Boy, 122.

[4] Oriental-motif jacket: (‘‘I don’t know that Ezra would have noticed me if I had not been wearing that jacket.’’) Olga Rudge, taped interview with P. D. Scott, Berkeley, Calif., 12 Oct 1985.

[5] ‘‘wild girl from Cincinnati’’: Secrest, Between Me and Life, 320.

[6] ‘‘between a chapel and a bordello’’; ‘‘folded up like damp handkerchiefs’’: Interview with Bettina Bergery, in ibid., 317.

[7] ‘‘Who is that?’’: Olga Rudge interview, in Ezra Pound: An American Odyssey (film), ed. Lawrence Pitkethly, 1981.

[8] The poet’s robustness; patriarchal attitude: Anderson, My Thirty Years’ War, 243–44.

[9] ‘‘Cadmium? amber?’’: Ethel Moorhead in Norman, Ezra Pound, 276.

[10] ‘‘without finding a congenial mistress’’: Ezra Pound to Picabia, in 391 magazine (1922).

[11] ‘‘The rent is much cheaper’’: Ezra Pound to John Quinn, summer 1921, EPC/YCAL.

[12] ‘‘as poor as Gertrude Stein’s’’: Hemingway, A Moveable Feast, 107.

[1] Stein did not find Pound amusing: Stein, in Norman, Ezra Pound, 245.

[14] ‘‘a beautiful picture ’’: Daniel Cory, ‘‘Ezra Pound, a Memoir,’’ Encounter, May 1968.

[15] Porcelain figure; basketwork of braids: Ezra Pound, ‘‘Medallion,’’ Hugh Selwyn Mauberly.

[16] Their next meeting: Olga Rudge, Research notebooks, ORP3/YCAL.

[17] Visitors who came: Interview with Robert Fitzgerald, in Norman, Ezra Pound, 310.

[18] ‘‘Me scusi tanto’’: Olga Rudge to Ezra Pound (pneumatique), 21 June 1923.

[19] ‘‘as wildly strange ’’: GA to Ezra Pound, [nd] 1923, EPC/YCAL.

[20] ‘‘note how elegant’’: 1996 addition, ORP/YCAL.

[21] ‘‘I noticed when we commenced’’: Antheil, Bad Boy, 121.

[22] ‘‘a riot’’: ‘‘The Mailbag,’’ New York Herald (Paris), 22 Dec 1923, ORP8/YCAL.

[23] ‘‘My piano was wheeled out’’: Antheil, Bad Boy, 133.

[24] ‘‘a very pretty sonority’’; Pound’s pieces: Irving Schwerke, ‘‘Notes of the Music World,’’ Chicago Tribune (Paris), 15 Dec 1923.

[25] ‘‘Can this really be . . . music?’’; ‘‘heaven-sent . . . repose’’: Louis Schneider, ‘‘Futurist Music Heard in Paris,’’ Chicago Tribune (Paris), 12 Dec 1923, ORP8/YCAL.

[26] ‘‘practice the Mozart’’: Ezra Pound to Olga Rudge (pneumatique), 1 Dec 1923.

[27] ‘‘Dolcezza mia’’: Olga Rudge to Ezra Pound, 23 Dec 1923.

The primary sources of this biography are the Olga Rudge Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (MSS54 YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (herein cited as ORP/YCAL); family memorabilia in three old trunks that I was privileged to research at Brunnenburg during Olga Rudge’s lifetime, now held by the Beinecke Library (cited as 1996 addition, ORP/YCAL); the Ezra Pound Collection (MSS53 YCAL: Series 2, Family correspondence, also held by the Beinecke Library, herein cited as EPC/YCAL; and MSS52 YCAL, cited as the EPAnnex).

Series 3 (ORP3): Notebooks are divided into two sections: I Ching notebooks (Boxes 93–99), daily records of the years 1966–86 arranged chronologically, containing flashbacks to earlier events recollected by Olga Rudge in later life; and Research notebooks (Boxes 99–101), transcripts of important correspondence and materials collected by Olga Rudge ‘‘to set the record straight,’’ arranged alphabetically by title or subject).

Series 8 (ORP8): Music (Boxes 142–47), an important section documenting Olga Rudge’s musical career, scrapbooks, notices, and clippings of Olga Rudge’s early performance history, concert programs, Vivaldi research, the history of the Concerti Tigulliani, arranged alphabetically by subject and type of material.

Secondary Sources

Ackroyd, Peter. Ezra Pound. London, Thames & Hudson, 1980.

Agenda 21, William Cookson, ed. (Ezra Pound Special Issue), 1979.

Aldington, Richard. Life for Life’s Sake. New York, Viking, 1941.

Aldington, Richard. Soft Answers. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1967 (‘‘Nobody’s Baby,’’ 88–129).

Anderson, Margaret. My Thirty Years’ War: The Autobiography. New York, Horizon, 1969.

Antheil, George. The Bad Boy of Music. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday Doran, 1945.

Ardinger, Richard, ed. ’’What Thou Lovest Well Remains’’: 100 Years of Ezra Pound. Boise, Idaho, Limberlost Press, 1986.

Bacigalupo, Massimo. The Formed Trace: The Later Poetry of Ezra Pound. New York, Columbia University Press, 1980.

Bacigalupo, Massimo. ed. Ezra Pound: Un Poeta a Rapallo. Genoa, Edicione San Marco dei Giustiniani, 1985.

Baldauf-Berdes, Jane L. Women Musicians of Venice: Musical Foundations, 1525–1855. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995.

Barnard, Mary. Assault on Mount Helicon: A Literary Memoir. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1934.

Beach, Sylvia. Shakespeare & Company. New York, Harcourt, Brace, 1959.

Bornstein, George, ed. Ezra Pound Among the Poets. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Bowen, Stella. Drawn from Life. London, Virago, 1984.

Brodsky, Joseph. Watermark. New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992.

Carpenter, Humphrey. A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound. New York, Dell Publishing (by arrangement with Houghton-Mifflin), 1990.

Carpenter, Humphrey. Geniuses Together: American Writers in Paris in the 1920s. London: Faber & Faber, 1988.

Chigiana: Rassegna Annuale di Studi Musicologici, XLI, Nuova Serie 21. Firenze, Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1989.

Chute, Desmond. ‘‘Poets in Paradise,’’ The Listener, 5 Jan 1956.

Cody, William J. T. ‘‘Ezra Pound: The Paris Years.’’ Unpublished paper, Conference on Creativity and Madness (Paris), 23 Sept 1990.

Conover, Anne. Caresse Crosby: From Black Sun to Roccasinibalda. Santa Barbara, Calif., Capra, 1989.

Conover, Anne. ‘‘Her Name Was Courage: Olga Rudge, Pound’s Muse and the ‘Circe/Aphrodite ’ of the Cantos.’’ Paideuma, Spring 1995.

Conover, Anne. ‘‘The Young Olga.’’ Paideuma, Spring 1997.

Cornell, Julien. The Trial of Ezra Pound: A Documented Account of the Treason Case by the Defendant’s Lawyer. New York, John Day, 1966.

Cory, Daniel. ‘‘Ezra Pound, a Memoir.’’ Encounter, May 1968.

Diggins, John P. Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1972. (See 246–47, 437–38, for EP’s Rome Radio broadcasts and view of Fascism.)

Diliberto, Gioia, Hadley. New York, Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

Dixon, Vladimir. ‘‘Letters of Ezra Pound and Vladimir Dixon.’’ James Joyce Quarterly, Spring 1992.

Doob, Leonard, ed. ’’Ezra Pound Speaking’’: Radio Speeches of World War II. Westport, Conn., Greenwood, 1978.

Doolittle, Hilda. End to Torment: A Memoir of Ezra Pound, ed. Norman Holmes Pearson. New York, New Directions, 1979.

Douglas, Norman. South Wind. New York, Macmillan, 1929.

Duncan, Ronald. All Men Are Islands. London, Rupert Hart-Davis, 1964.

Ede, Harold Stanley. Savage Messiah: Gaudier-Brzeska. New York, A. A. Knopf, 1931.

Elkin, Robert. Queen’s Hall, 1893–1914. London, 1944.

Fisher, Clive. Cyril Connolly: The Life and Times of England’s Most Controversial Literary Critic. New York, St. Martin’s, 1995.

Fitch, Noel Riley. Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation. New York, W. W. Norton, 1983.

Flory, Wendy Stallard. The American Ezra Pound. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1989.

Flory, Wendy Stallard. Ezra Pound and the Cantos: A Record of Struggle. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1980.

Ford, Hugh. Four Lives in Paris. San Francisco, North Point, 1987.

Gallup, Donald C. Ezra Pound: A Bibliography, 2d ed. Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1983.

Gallup, Donald C. T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound: Collaborators in Letters. New Haven, Conn., Wenning/Stonehill, 1970.

Gallup, Donald C. What Mad Pursuits! More Memories of a Yale Librarian. New Haven, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, 1998.

Ginsberg, Allen. ‘‘Allen Verbatim.’’ Paideuma, Fall 1974.

Gordon, David M., ed. Ezra Pound and James Laughlin: Selected Letters. New York, W. W. Norton, 1994.

Gourmont, Remy de. The Natural Philosophy of Love, with translator’s postscript by Ezra Pound. New York, Boni & Liveright, 1922.

Guggenheim, Peggy. Out of This Century. New York, Doubleday, 1980.

Hall, Donald. Remembering Poets. New York, Harper & Row, 1978.

Hall, Donald. ‘‘Ezra Pound, An Interview.’’ Paris Review 28, 1962.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1964.

Hemingway, Ernest. Selected Letters, 1917–1961, ed. Carlos Baker. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

Heymann, C. David. Ezra Pound: The Last Rower. New York, Viking, 1976.

Huddleston, Sisley. In and About Paris. London, Methuen, 1927.

Kenner, Hugh. The Pound Era. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1972.

Kirchberger, Joe H. The First World War: An Eye Witness History. New York, Facts on File, 1992.

Kodama, Sanehide, ed. Ezra Pound in Japan: Letters and Essays. Redding Ridge, Conn., Black Swan, 1987.

Laughlin, James. Ez as Wuz. Port Townsend, Wash., Graywolf, 1987.

Levy, Alan. Ezra Pound, the Voice of Silence. New York, Permanent Press, 1988.

Lindberg-Seyersted, Brita, ed. Pound/Ford: The Story of a Literary Friendship. New York, New Directions, 1982.

Littlewood, Ian. Paris: A Literary Companion. New York, Franklin Watts, 1988.

McAlmon, Robert. Being Geniuses Together, 1920–1930, rev. and enlarged ed., with Kay Boyle. San Francisco, North Point, 1968.

McDougal, Stuart Y. Ezra Pound and the Troubadour Tradition. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1972.

McGuire, William. Bollingen: An Adventure in Collecting the Past. Princeton, Princeton University Press (Bollingen Series), 1982.

Mackenzie, Compton. Extraordinary Women: Theme and Variations. New York, Vanguard, 1928.

Mackenzie, Compton. My Life and Times: Octave Five (1915–1923). London, Chatto & Windus, 1966.

Mackenzie, Faith Compton. As Much As I Dare. London, Collins, 1938.

MacLeish, Archibald, with R. H. Winnick. An American Life. New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 1992.

McNaughton, William. ‘‘The Secret History of St. Elizabeth’s.’’ Unpublished paper, Ezra Pound International Conference at Brunnenburg, July 1997.

Meacham, Harry M. The Caged Panther: Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s. New York, Twayne, 1967.

Menuhin, Yehudi. The Compleat Violinist: Thoughts, Exercises, and Reflections of an Itinerant Violinist, ed. Christopher Hope. New York, Summit Books, 1986.

Meyers, Jeffrey. The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis. London, Routledge Kegan-Paul, 1980.

Mullins, Eustace. This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound. New York, Fleet, 1961.

Norman, Charles. Ezra Pound. New York, Macmillan, 1960.

O’Connor, William Van, and Edward Stone, eds. A Casebook on Ezra Pound. New York, Crowell, 1959.

O’Grady, Desmond. ‘‘Ezra Pound, a Personal Memoir.’’ Agenda 17, 1979.

Paige, D. D., ed. The Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907–1941. New York, Harcourt Brace, 1950.

Paideuma: A Journal Devoted to Ezra Pound Scholarship, ed. Carroll F. Terrell. Orono, Maine.

Painter, George. Marcel Proust: A Biography. New York, Random House, 1989.

Perloff, Marjorie. ‘‘The Contemporary of Our Grandchildren: Pound’s Influence,’’ in Ezra Pound Among the Poets, ed. George Bornstein. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Pitkethly, Lawrence, ed. Ezra Pound: An American Odyssey (film). Unpublished interviews with Olga Rudge and Mary de Rachewiltz, New York Center for Visual History, 1981–82.

Pinzauti, Leonardo, L’Accademia Musicale Chigiana: Da Boito a Boulez. Milan, Editoriale Electra, 1982.

Pound, Ezra. Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony. Paris, Three Mountains Press, 1924.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New York, New Directions, 1989.

Pound, Ezra. Guide to Kulchur. London, Faber & Faber, 1934.

Pound, Ezra. Spirit of Romance. London, J. M. Dent, 1910.

Pound, Omar, and Robert Spoo, eds. Ezra and Dorothy Pound: Letters in Captivity, 1945–1946. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Putnam, Samuel. Paris Was Our Mistress. New York, Viking, 1947.

Rachewiltz, Mary de. Discretions. Boston, Little Brown/Atlantic Monthly, 1971.

Rachewiltz, Mary de. ‘‘Pound as Son: Letters Home.’’ Yale Review, Spring 1986.

Raffel, Burton. Ezra Pound: Prime Minister of Poetry. Hamden, Conn., Archon, 1984.

Rattray, David. ‘‘Weekend with Ezra Pound.’’ Nation, 16 Nov 1957.

Reck, Michael. Ezra Pound: A Close-up. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Redman, Tim. Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Studies in American Literature), 1991.

Rudge, Olga. Facsimile di un Autografo di Antonio Vivaldi. Siena, Ticci Editore Libraio, 1947.

Sarde, Michele. Colette: A Biography, tr. Richard Miller. New York, William Morrow, 1980.

Schafer, R. Murray, ed. Ezra Pound and Music: The Complete Criticism. New York, New Directions, 1977.

Secrest, Meryle. Between Me and Life: A Biography of Romaine Brooks. New York, Doubleday, 1974.

Sieburth, Richard. Instigations: Ezra Pound and Remy de Gourmont. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1978.

Simpson, Eileen. Poets in Their Youth: A Memoir. New York, Random House, 1982.

Simpson, Louis. Three on the Tower: The Lives and Works of Ezra Pound, T. S.

Eliot, and William Carlos Williams. New York, William Morrow, 1975.

Stead, C. K. Pound, Yeats, Eliot, and the Modernist Movement. London, Macmillan, 1986.

Stock, Noel. The Life of Ezra Pound. New York, Pantheon, 1970.

Stock, Noel. Ezra Pound: Perspectives. Chicago, Henry Regnery, 1965.

Szasz, Thomas S. Law, Liberty, and Psychiatry. New York, Macmillan, 1963.

Terrell, Carroll F. A Companion to the Cantos of Ezra Pound, vols. 1 and 2. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1980, 1984.

Thomson, Virgil. Virgil Thomson. New York, A. A. Knopf, 1966.

Tomalin, Claire. Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life. New York, A. A. Knopf, 1987.

Torrey, E. Fuller. The Roots of Treason: Ezra Pound and the Secrets of St. Elizabeth’s. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1984.

Torriti, Piero. Siena: The Contrade and the Palio. Florence, Italy, Bonechi, 1988.

Tytell, John. Ezra Pound: The Solitary Volcano. New York, Doubleday, 1987.

Valesio, Paolo. Gabriele d’Annunzio: The Dark Flame. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1992.

Vannini, Armando. L’Accademia Musicale Chigiana. Siena, Tipografia ex-Cooperativa, ca. 1952.

Ward, Margaret. Maud Gonne: A Biography. New York, Harper-Collins, 1990.

Watson, Steven. Strange Bedfellows: The First American Avant-Garde. New York, Abbeville, 1991.

Weinberger, Eliot. ‘‘A Conversation with James Laughlin.’’ Poets and Writers, May–June 1995.

West, Rebecca. The Meaning of Treason. New York, Viking, 1947.

Wickes, George. Amazon of Letters: The Life and Loves of Natalie Barney. New York, Putnam, 1976.

Wickes, George. Americans in Paris. New York, Doubleday, 1969.

Wilhelm, J. J. Ezra Pound in London and Paris, 1908–1925. University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990.

Wineapple, Brenda, Sister/Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein. New York, G. P. Putnam, 1996.

Witemeyer, Hugh. The Poetry of Ezra Pound: Forms and Renewal, 1908–1920. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1969.

Witemeyer, Hugh. ed. Pound/Williams: Selected Letters of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. New York, New Directions, 1996.

Yeats, William Butler. Autobiography. New York, Macmillan, 1965.

Yeats, William Butler. Letters, ed. Allan Wade. London, Hart-Davis, 1954.

Zinnes, Harriet, ed. Ezra Pound and the Visual Arts. New York, New Directions, 1980.