Surrealism and Space in the Installation Design

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Aenzo Scalacci (1923-1969) |

Aenzo Scalacci (1923-1969) |

Surrealism and Space in the Installation Design

T. J. Demos

Duchamp's Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942 (Part 1)*

Entwined Spaces

In October of 1942, two shows opened in New York within one week of each other, both dedicated to the exhibition of Surrealism in exile, and both representing key examples of the avant-garde's forays into installation art. First Papers of Surrealism, organized by André Breton, opened first. The show was held in the lavish ballroom of the Whitelaw Reid mansion on Madison Avenue at Fiftieth Street. Nearly fifty artists participated, drawn from France, Switzerland, Germany, Spain, and the United States, representing the latest work of an internationally organized, but geopolitically displaced, Surrealism. The "First Papers" of the exhibition's title announced its dislocated status by referring to the application papers for U.S. citizenship, which emigrating artists (including Breton, Ernst, Masson, Matta, Duchamp, and others) encountered when they came to New York between 1940 and 1942. But the most forceful sign of the uprooted context of Surrealism was the labyrinthine string installation that dominated the gallery, conceived by Marcel Duchamp, who had arrived in New York from Marseilles in June of that year. The disorganized web of twine stretched tautly across the walls, display partitions, and the chandelier of the gallery, producing a surprising barrier that intervened in the display of paintings.[1]

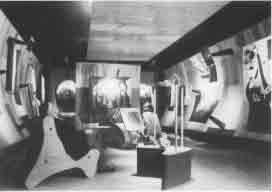

The second exhibition was the inaugural show of Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery on Fifty-seventh Street, which displayed her collection of Surrealist and abstract art. Guggenheim gave Frederick Kiesler free rein to design the exhibition space. Originally a Romanian though Austrian by choice, Kiesler had practiced architecture in Vienna while connected with the Bauhaus and De Stijl avant-gardes before settling in New York in 1926. His installation for Guggenheim's gallery was more extensive than that of First Papers. In contrast to Duchamp's menacing barrier, Kiesler's design went to extraordinary lengths to integrate works into a gallery space that became sculptural. In the Surrealist Gallery, frames were removed from paintings in order to produce an uninterrupted connection with viewers. Paintings supported by wooden arms floated away from the walls, which were rendered concave. Kiesler painted the background and ceiling black and the floor turquoise to darken the environment, and alternate sides of the gallery were illuminated for two minutes each, divided by a few seconds' pause. In the Abstract Gallery, works by artists such as Kandinsky, Arp, and Mondrian were hung in midair with string. Interactive and mobile, they could be variously tilted and suspended at any height.

Marcel Duchamp; Installation for First Papers of Surrealism, New York, 1942.

While the two installations appear to have little in common, within the scholarship there is an all-too-quickly accepted continuity between them. It is common to read, for example, that Duchamp's offered a model for the "transparent" relation between viewer and work of art established in Kiesler's installation.[2] Ultimately, this interpretive position derives from Kiesler, who claimed Duchamp's work as a guide for his own interests in what he called "correalism," or the establishment of the complete integration of artistic media, space, and viewers. "It is architecture, sculpture and painting in one," Kiesler observed of Duchamp's work.[3] However, to claim that the two installations were similar ignores their antithetical forms and effects. While Kiesler employed string to support paintings, its use minimized any physical separation between painting and viewer. This was to facilitate the transformation of paintings into what Kiesler called "eidetic images," as if they had lost their materiality and hovered as dream images in space without physical support or frame. Kiesler's string was the answer to his desire to negate any nonaesthetic barriers between viewer and work of art, or rather to render those barriers aesthetic. Duchamp's string, on the other hand, acted as the maximal obstacle between paintings and viewing space. It even eliminated viewing areas between partitions. If Kiesler made every architectural attempt at an uninhibited "correlation" between the viewer's perception and the aesthetic objects holding his attention, then Duchamp's installation achieved the utter opposite by restricting visual access to the paintings, effectively dislocating objects from their visible exhibition, and subjecting the gallery space to a stubborn and disorienting labyrinth of string.

To accept any continuity between the two installations, moreover, is a direct result of a failure to adequately historicize the aesthetic developments of 1942 and especially those relating to installation art. Against conventional opinion, I argue that each installation articulated a very unique response to the avant-garde's geographical, political, and historical displacement. Duchamp's installation, far from a flippant work or a simple, Surrealist-inspired gesture, acted as a sophisticated negation of certain reactionary tendencies within Surrealism once it entered into exile. This becomes even more intelligible, in fact, through a revised comparison with Kiesler's designs. The installations, then, represent two models, opposed but productively related, with which we might measure the historical antinomies of the avant-garde in its context of exile during World War II. By rendering the exhibition's container biomorphic and fusional, Kiesler's installation provided what can be seen as a compensatory "home" for a displaced Surrealism. Conversely, Duchamp's installation enforced a "homeless" space that resonated with geopolitical dislocation and refused any compensatory strategies of display. Together, they reveal the historical entwinement of the desires for the home and the insistence on a homeless reality, which defines the displaced avant-garde in 1942.

Frederick Kiesler; Surrealist Gallery, Art of This Century Gallery, New York, 1942.

In this regard, the condition of displacement suggests a new way to comprehend developments in installation art during the war years, different from conventional art-historical genealogies that see them as solely related to the critiques of institutions and commodification; for installation, embodying the physical and ideological mediation between objects, viewers, and their surrounding space, immediately concerns issues of placement, location, and contextualization-the very issues that became sensitized and overdetermined in the context of geopolitical dislocation. Once we accept the proposition that the construction of installations in 1942 was in some way more than superficially related to the artists' own displacement, we need to ask what was at stake? How did the work of installation define, analyze, negotiate, or compensate for the condition of displacement?

Displacement and Mythologization

Before directly addressing the installations, it is necessary to retrace the developments of the 1930s to understand how Surrealism arrived at its conflicted position in 1942. From its beginnings, Surrealism had been engaged with "homelessness," but a homelessness defined through psychoanalytic theory and particularly by Freud's essay "The Uncanny" ("unhomely," or unheimlich in German). According to Hal Foster, who has explored the artistic and theoretical terms of the Surrealist uncanny at length, Surrealist art probed the primordial ties between mother and child in "nonregressive ways."[4] This Surrealism was consequently dominated by shock, montage, doubling, and estrangement, which blocked any regressive temptations to retreat to the maternal home (the ultimate locus of the heimlich, according to Freud). This work thus reflected the realization of the irredeemable loss of the mother-child union (due to repression, castration threats, paternal injunctions, social law, etc.). The refusal of any facile reconciliation was precisely the productive tension and homeless condition in which Surrealism thrived.

Kiesler; Abstract Gallery, Art of This Century Gallery, New York, 1942.

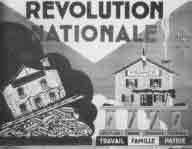

Its homelessness, however, would be significantly redefined between 1935 and 1942. By 1935 it had transformed into an oppositional politics that refused the "home" as ideological site of the national. This antinational politics of homelessness united the notoriously antagonistic Bataille and Breton in solidarity, bringing them into the streets as Contre-Attaque, which occupied a contestatory space outside nationalism's ideology of the home. If the street once represented the privileged Surrealist site of amorous fantasy, the disorienting "coincidence" or "l'umour fou," it soon became the place in which to protest the nationalism of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, but also that of France's Popular Front government. Cotre-Attaque combated the ideology of the "home," which had become a propagandistic metaphor for national identity in France. In one of their many fliers, they claimed that

A man who acknowledges the homeland, a man who struggles for the family, is a man who commits treason. . . .The homeland stands between man and the wealth of the soil. It requires that the products of human sweat be transformed into cannons. It renders the human being a traitor to his fellow men. The family is the foundation of social constraint . . . [and] has served as a model of all social relations based on the authority of bosses and their contempt for their fellow men. Father, homeland, boss: such is the trilogy that serves as the basis of the old patriarchal society and, today, of fascist idiocy.[5]

The figure of the home, frequently referenced in political rhetoric and propaganda posters of the collaborationist Vichy government, and in France of the 1930s, had become a powerful emblem for nationalism. But it was filled with contradictions. It signified the familial integration of social classes and regional divisions within a homogeneous spatial and social unit, but one that nevertheless existed under patriarchal authority. It acted as a unifying metaphor for society (grouped together in the national home), even though its private architecture was otherwise seen as economically, spatially, and socially divisive.[6] The home, with nationalism, patriarchy, and capitalism condensed under its roof, was thus a central target of Contre-Attaque. Politically homeless, the Surrealists counterattacked nationalization as a false form of social integration, which they presciently claimed would ultimately result in war between nations, betraying any truly unifying postnational organization of society. Their homeless politics, however, remained rhetorical and did not enter into artistic form. This owed mainly to the overdetermination of politicized art by the socialist realism of the Communist Party, with which the Surrealists broke ties. As a result, the Surrealist defense of artistic freedom and individuality-against the Party's controlling doctrine–resulted in a problematic and limiting refusal of any politicized art in the later thirties.[7]

Vichy political poster Circa 1942.

Increasingly isolated by their critique of nationalism, the Surrealists soon found themselves without political party or popular support in a period increasingly dominated by party politics and nationalization on the right and the left.[8] Consequently their homelessness again shifted sites. Due to the political situation that proscribed any public, independent position outside of dominant parties, Surrealism, under Breton, was forced to relocate its protests within the bourgeois space of the gallery. This effectively concluded its homeless political activities on the street.[9] There, the street became merely a nostalgic representation. This was best exemplified in the "Surrealist Street," the hallway filled with mannequins fantastically dressed by different artists, which was assembled in the 1938 exhibition at the prestigious Galeries Beaux-Arts. With the active struggle against nationalism displaced by an art that defined its independence through its resistance to politicization (at least in Breton's terms, marked by the return to the aesthetics of the uncanny), Surrealism increasingly changed from a self-fashioned political and artistic movement into a predominantly artistic one.

By 1940, with the German occupation of France and the gradual emigration of many Surrealists to New York, the movement's political disenfranchisement, loss of artistic relevance, and resulting anomie were only heightened.[10] While homelessness was once defined by the psychic uncanny and later through the politics of antinationalism, it now referred to the lived experience of geopolitical dislocation. As a result, Surrealism was forced to renegotiate its new existence in the context of exile in the U.S., a country that hadn't even appeared on its 1929 "Surrealist Map of the World." Abandoning Europe to its self-destruction was in many ways the last resort of a melancholy defeatism for a movement that had long struggled against nationalism and war. In the "Prolegomena to a Third Surrealist Manifesto or Not," written in New York in 1942, Breton registered such a resignation: "Man must flee the ridiculous web that has been spun around him: so-called present reality with the prospect of a future reality that is hardly better."[11] Faced with the loss of its national and geographical home (one that the Surrealists never overtly supported or celebrated) due to the unfathomable devastation of world war, coupled with the recognition of its political impotence, Breton outlined the surprising new directions of Surrealism in its journal VVV in 1942: "V as a vow . . . to return to a habitable world." Once committed to the tension of psychic homelessness, and later to its politicization as an antinational politics, Surrealism, brought to its knees in geopolitical exile, now longed for a home.

Surrealist Map of the World, 1929.

If Breton's Surrealism had gradually but begrudgingly moved from the street to the salon during the 1930s, then in New York it moved from the salon into myth, where it could "return to a habitable world" disallowed by the "so-called present reality" of dislocation. Myth, in other words, offered a way to balance ideological contradictions in a period of extreme compromise. Breton's new myth, supported by a number of artists (Matta above all), corresponded to a belief in what he called the "Great Transparents." These refer to entities that surround human beings but remain invisible to the senses. "Man is perhaps not the center, not the focus of the universe," he reasoned in the most extensive passage on the Great Transparents:

One may go so far as to believe that there exists above him on the animal level beings whose behavior is as alien to him as his own must be to the day fly or the whale. There is nothing that would necessarily prevent such beings from completely escaping his sensory frame of reference since these beings might avail themselves of a type of camouflage, which no matter how you might imagine it becomes plausible when you consider the theory of form and what has been discovered about mimetic animals.[12]

Matta produced a drawing for the article. Nearly abstract, the work balances between linear scrawls and suggestions of biomorphic and anthropomorphic shapes, compositionally divided into separate circular areas. The transparency of forms suggests the diaphanous quality of the mythical beings nearly "escaping our sensory frame of reference." For his illustrated essay on myths in the First Papers catalog, Breton used a photograph by David Hare to illustrate Les Grands Transparents.[13] The photograph's nude figure is only partly legible, its upper half disfigured through brûlage, suggesting a transcendent pneumatic being from another world. Breton further defined his myth by locating the habitat of the Great Transparents in "the realm of the Mothers," to whose credit it was Tanguy's to have "visually penetrated" in his work of 1942.[14] While avant-garde montage and fragmentation had earlier encouraged a materialist focus on the constructed ness of representation, here that fragmentation was made to point to a metaphysical, idealist beyond.[15] Although the expressions of geopolitical homelessness intersected with the intimations of uncanny experience, the new focus was nevertheless on habitability, secure space, and a restorative and compensatory subjectivity, and not on shock, destabilization, or fragmentation. Perhaps as an attempt to complicate matters in his "Prolegomena," Breton referred to Roger Caillois's theory of "mimetic animals." In a recent essay, Caillois examined the conspicuous insectoid mimicry of the adoption of one form to another, which he termed a "homomorphic" assimilation. This transformation, however, could never suggest the habitability Breton wanted. Rather, homomorphy, according to Caillois, describes a state of radical loss, subjective detumescence, and out-of-placeness. It announces a disorientation of total desubjectivization rather than a comforting space of mythical Heimlichkeit. Caillois's mimicry dispossesses being of its physical location so that it "no longer knows where to place itself." What results is a schizophrenic "depersonalization by assimilation to space," a sudden materialization in which "the body separates from its thought."[16] Conversely, Breton's myth anthropomorphizes and deifies space. Instead of representing an inquiry into the de-individualizing generalization of space, it proposed a new religion.

Matta; Les Grands Transparents.

The problem was that Breton's myth represented an escape from the sociopolitical, rather than a complicating development within it. While some on the left had in fact suggested that their own revolution exploit the regressive desires and forces of the atavistic, which fascism had instrumentalized, Breton's myth, and the aesthetic constructions it encouraged, retreated to a homely space that was postrevolutionary.[17] Contemporary audiences were immediately suspicious of the new directions of Surrealism, particularly against the backdrop of fascism. When Meyer Schapiro first read the new issue of VVV, he responded, "This is the issue on which surrealism may well fall; it is an assault on the construction de l'homme."[18] Harold Rosenberg flatly replied that Breton's "desire for a new myth is reactionary." Recalling Contre-Attaque's antinationalism, Rosenberg advocated the "the painful negation of myths, and of the myth-seeds, Church, Fatherland, Family," especially since "the production of myths, which disintegrate humanity into warring cults, has become the chief occupation of the world's most brilliant talents, such as Goebbels, Mussolini, and thousands of editors, advertising men, and information specialists."[19] And in perhaps the most far-reaching examination of myth, Dialectic of Enlightenment, exiled Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer found, contra Breton, that far from being without myth, society was dominated by it. Fascism, however, was only its most barbaric manifestation. Rather than revolutionize myth against fascism (Bloch's approach), or negate fascist mythology with Enlightenment science (liberal humanism's answer), the critical goal of Adorno and Horkheimer was to uncover how the Enlightenment itself reverts into myth. For them, it was urgent to reveal how myth enforces a deadly forgetfulness regarding history and provokes the idolization of capitalism through increasingly powerful means of control and manipulation. Were Adorno and Horkheimer to read Breton's call for a "new myth," they would likely have viewed it as the creation of a compensatory shield against the traumas of exile and war, an acritical mimicry of fascism, and an impossible attempt to build a home in an age of homelessness.

Framelessness

If Surrealism in exile longed to return to a "habitable world" through its mythological construction, then this was accompanied by a corresponding shift in its exhibition presentation that would return Surrealist objects to a habitable space. Frederick Kiesler provided such a space in the installation design for Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery. Increasingly identified with Surrealism and its nostalgia for the home during the early 1940s, Kiesler, also a displaced person, reiterated Breton's call for a new myth: "The artist's work stands forth as a vital entity in a spatial whole, and art stands forth as a vital link in the structure of a new myth."[20] His own myth sought an aesthetic unity that would propose its own kind of metaphysics and idealism: that of pure presence and absolute integration. The installation pursued this ideal integration by attempting to eliminate any mediation between painting and viewer, or between art objects and surrounding space. This explains the urge behind the removal of frames and the turn toward string as a support mechanism, which would introduce art objects within the viewer's own physical area and away from the separate wall, thus closely connecting the viewer to the art object. Furthermore, the designs of the spaces corresponded to the general aesthetic of the displayed work, reconciling objects and context. The Surrealist Gallery's walls were hollowed out, mimicking the biomorphic form of many of the paintings' compositions, whereas the paintings of the Abstract Gallery, mostly of a geometric abstraction, were supported by cords in geometric shapes. Similarly, the viewing space would assimilate visitors by offering biomorphically designed furniture, and paintings hung at different levels corresponding to dynamic viewing perspectives.

David Hare; Les Grandes Transparents, 1942.

Kiesler was explicit about his motivations. Turning to a utopian conception of language and vision based in primitivist beliefs, he defined and justified the aims of the Guggenheim installation. It was meant "to break down the physical and mental barriers which separate people from the art they live with, working toward a unity of vision and fact as prevailed in primitive times."[21] Kiesler proposed to achieve this unity through the dissolution and aesthetic sublation of the frame:

Today, the framed painting on the wall has become a decorative cipher without life and meaning. . . . Its frame is at once symbol and agent of an artificial duality of "vision" and "reality," or "image" and "environment," a plastic barrier across which man looks from the world he inhabits to the alien world in which the work of art has its being. That barrier must be dissolved: the frame, today reduced to an arbitrary rigidity, must regain its architectural, spatial significance.[22]

The unity of "vision and reality" that Kiesler sought was nothing less than a magical return to a prelinguistic unity where the difference between sign and referent-made obvious by the frame-would dissolve. The ultimate goal was that the reunified plenitude of a totalized aesthetic space would efface the experience of barriers and dislocations, and this reverberated with the war-torn world of 1942 and Kiesler's own experience of dislocation. In this regard, his installation designs concretized Breton's demand for a myth to restore habitability, and it did so by constructing a fusional installation design as a response to the anomie of exile. The continual focus on developing a "livable home," a "habitable space," which one frequently encounters in Kiesler's writings, exposes the homeless anxiety that marks his designs. This, too, Kiesler articulated. In "Cultural Nomads," published some years later, he specified the angst of dislocation that informs the regressive character of his work: "Moving from one apartment to another, from one town to another, or across borders into different lands. . . . We live an emergency life, a deadline life. . . . The core of the civilized nomad's life . . . is hollow, and we gobble down anything to fill the emptiness."[23]

Kiesler; Endless House, 1950.

Kiesler's installation design, more specifically, "filled the emptiness" of homelessness through the aesthetic construction of a space redolent of a fantasy of the psychic and maternal home (bringing to mind Breton's mythical "realm of the Mothers"). The gallery was ultimately conceived as a canny interior of a body, with the concave walls suggesting a uterine form. Protruding "arms" would hold up paintings and the lighting effects of the gallery would "pulsate like your blood."[24] For Kiesler, this homely architecture was a long-term pursuit, later exemplified in his spheroid architectural models, such as the one for Endless House of 1950.[25] In the installation, the emphasis on biomorphic shapes, the attempt to fuse the viewer with an egglike or uterine form, in addition to Kiesler's own desires for such a spatial, linguistic, and psychic plenitude, represented one response to the experience of geopolitical deracination: to regress to a primordial intrauterine home. A psychoaesthetic homeliness answered a geopolitical homelessness, compensating for the contradictions in Surrealism's identity (politically antinational, but insufferably geographically displaced; anticapitalist but forced into the salon).

Kiesler's rhetoric repeats a Surrealist tradition, at least among its expatriate members. Matta, a displaced Chilean in Paris, had expressed intrauterine spatial fantasies for a model apartment just a few years earlier: "Man yearns for the obscure thrusts of his beginning, which enclosed him in humid walls where the blood beats near the eye with the sound of the mother. . . . We need walls like damp sheets which lose their shapes and wed our psychological fears."[26] And the Romanian Tristan Tzara had made similar appeals in 1933, conspicuously after his involvement in the expatriate community of Zurich Dada and its vociferous attacks on nationalism during World War I. Like Matta, he extolled a return to the "intrauterine life" and "prenatal comfort" of the primordial forms of the house, like the Eskimo yurt, the grotto, or tent, whose spherical morphology had been displaced by the "castrative aesthetics" of modern architecture. This had prepared the ground for the "self-aggressiveness that characterizes modern times."[27]

But during the advancing 1930s, homely regression had turned dangerously problematic; for the regression implied in its spatial model, once merely a utopian avant-garde aim, now shared its logic with the aspirations of fascism. If the home as rhetorical figure had already been co-opted by nationalist discourse, then so had the fantasy of fusion. Problematized at the time by Lacan, this fantasy of an intrauterine architecture suggested the longing for the spatial resolution of the anxiety of psychic division and physical fragmentation that characterized fascism. In a 1938 article on "Family Complexes," Lacan related the "the desire of the larva" to fascist attempts to return to an imaginary physical habitat. As a regressive reaction to a paranoid threat of bodily and psychic fragmentation, the subject compensates through fantasies of fusion, absorptive architectural spaces, and all–encompassing spectacles. The "prenatal habitat," less a literal architecture than a matrix of regressive desires, held the myth of "the perfect assimilation of everything into a being." Within this matrix, Lacan notes, "will be recognized the nostalgias of humanity: the metaphysical mirage of universal harmony; the mystical abyss of affective fusion; the social utopia of totalitarian tutelage-all resulting from the fear of a paradise lost before birth and from the most obscure aspirations for death."[28] It would appear that Kiesler's goal to eliminate the frame, even though carried out in an avant-garde context antithetical to fascism, shared these desires, but without redirecting them against fascism. Framelessness did not open onto the sociopolitical, but disavowed it in order to compensate for, by escaping from, the loss of dislocation.[29]

* T. J. Demos; Duchamp's Labyrinth: "First Papers of Surrealism", 1942 - October, Vol. 97. Summer, 2001, pp. 91-106.

Duchamp's Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942 (Part 2)

Notes

[1] Duchamp commissioned John Schiff to photograph the space. The catalog credits Duchamp with "his twine," "sixteen miles of string," though probably around one mile was used. For a documentary account of the show, its history and reception, see Lewis Kachur, "The New World: 'First Papers of Surrealism,"' in Displaying the Marvelous: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali and Surrealist Exhibition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001).

[2] Cynthia Goodman suggests: "One source for the illusion of 'transparency' may have been Duchamp, whose concurrent installation of Surrealist art at the Whitelaw Reid mansion suspended the paintings among sixteen miles of string" ("Frederick Kiesler: Designs for Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery," Arts Magazine 51 [June 19771, pp. 93-94). Also see her more recent "The Art of Revolutionary Display Techniques," in Fredrick Kiesler (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1989). On the relation between Kiesler and Duchamp, who first met in 1925 at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, et Industriels Modernes in Paris, see Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "Frederick Kiesler and the Bride Stripped Bare" in Frederick Kiesler 1890-1965, ed. Yehuda Safran (London: Architectural Association, 1989).

[3] Frederick Kiesler, "Design-Correlation: Marcel Duchamp's 'Big-Glass"' (1937), in Fredrick Kiesler: Selected Writings, ed. Siegfried Gohr and Gunda Luyken (Ostfieldern bei Stuttgart: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1996, p. 38.

[4] Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993). Foster notes that for the Surrealists, "refinding a lost home is one with facing a deathly end," p. 206. Also see Rosalind Krauss's discussion of the Surrealist uncanny in "Corpus Delicti," in L'Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism (New York: Abbeville Press, 1986).

[5] "La Patrie et la Famille" (1936), signed by Bataille, Breton, Maurice Heine, and Georges Péret, reprinted in Tracts Surréalistes et Déclarations Collectives 1922-1939, ed. Jose Pierre (Paris: Le Terrain Vague, 1980), pp. 293-94. See also "Les 200 Familles," "Appel à I'Actiom," "Sous le Feu des Canons Français . . . et Alliés," "Ni de Votre Gurre ni de Votre Paix!" and "N'Imitez pas Hitler!"

[6] For an extensive examination of the development of nationalism in France, see Fascist Visions: Art and Ideology in France and Italy, ed. Matthew Affron and Mark Antliff (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

[7] For Breton's statements on this posture, see his "Speech to the Congress of Writers," in Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1982) and, along with Leon Trotsky, "Manifesto: Towards a Free Revolutionary Art," Partisan h i m 4, no. 1 (Fall 1938); reprinted in Free Rein, trans. Michel Parmentier and Jacqueline d’Ambroise (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

[8] Consider Jean Grenier's criticism of Surrealism in 1936 in the Nouvelle Revue Française: [Breton] proclaims the rights of the intellect and sides for the ideal Revolution, against actual revolutionaries. But that is quite useless: the age of heresies is over.. . we are now in the age of orthodoxies. . . . To be a revolutionary, today against Stalin, is like being a monarchist against Mauras and Catholic against Pius X. These are very noble attitudes, but they are admissible only for young people. Maturity . .. hungers for achievements. What is urgent is not to proclaim a faith, but to join a party. Cited in Susan Suleiman, Between the Street and the Salon: The Dilemma of Surrealist Politics in the 1930s, in Visualizing Theory, ed. Lucien Taylor (New York: Routledge, 1994), p. 157, n. 28.

[9] See Suleiman, who traces "the gradual, reluctant, perhaps totally unwilling but nevertheless indubitable movement of Surrealism during the 1930s from the street to the salon," p. 149. Suleiman notes that this also owed to a disillusionment with Contre-Attaque's protests, which problematically mimicked fascist street tactics.

[10] For the history of the avant-garde exodus from Europe in the late thirties and early forties, see Martica Sawin's Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995) and Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, ed. Stephanie Barron (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1997).

[11] André Breton, "Prolegomena to a Third Surrealist Manifesto or Not" (1942), Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), p. 286.

[12] "Prolegomena," p. 293.

[13] Other illustrated "Myths" included "L'Age d'or," Orpheus, The Graal, The Philosopher's Stone, The Automaton, Triumphante Science, Le Surhomme, and the Myth of Rimbaud (First Papers of Surrealism [New York: Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies, Inc., 19421). The catalog was partially designed by Duchamp. A barely disguised reference to the transformation of violence and warfare into cheesy art, its cover photograph depicted a stone wall perforated by bullet holes, while the back, in parodic reverse, showed a close-up photograph of Swiss cheese.

[14] André Breton, "What Tanguy Veils and Reveals," View 2 (May 1942), n. p.

[15] Breton's idealistic Surrealism, however, had long been challenged by Bataille's materialism. See Bataille's critique of Breton's "Second Surrealist Manifesto," "The 'Old Mole' and the Prefix Sur in the Words Surhomme [Superman] and Surrealist," in Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, trans. and ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985).

[16] Roger Caillois, "Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia," trans. John Sheplev, October 31 (Winter 1984), pp. 28, 30. Caillois also considered the intrauterine nostalgia of mimicry, but quickly dismissed it as paradoxical: "to employ a psychoanalytic vocabulary and speak of reintegration with original insensibility and prenatal unconsciousness" would result in "a contradiction in terms" precisely because "the generalization of space" comes "at the expense of the individual," p. 31.

[17] For example, Ernst Bloch advocated the utilization of a dialectical conception of myth for the revolution against fascism in his Erbschaft dieser Zeit (Hritage of Our Times) of 1935. Hal Foster discusses Bloch and the potential for the dialectical reclamation of myth as antifascist within Surrealism in "Outmoded Spaces," in Compulsive Beauty.

[18] In a letter to Kurt Seligman, cited in Sawin, p. 217.

[19] This is in the form of a debate between three fictional characters in Rosenberg's "Breton-A Dialogue," in View 3, no. 2 (Summer 1942),composite quotation, n.p.

[20] Kiesler, "Notes on Designing the Gallery," in Selected Writings, p. 44.

[21] Kiesler, "Design Correlation," p. 76. Also, "Primitive man knew no separate worlds of vision and of fact. He knew one world in which both were continually present within the pattern of everyday experience. And when he carved and painted the walls of his cave or the side of a cliff, no frames or borders cut off his works of art from space or life-the same space, the same life that flowed around his animals, his demons and himself" ("Notes on Designing the Gallery," in Selected Writings, p. 42).

[22] "Notes on Designing the Gallery," p. 42.

[23] Frederick Kiesler, "Cultural Nomads" (1960), in Selected Writings, p. 98. Similarly he explained: "We will create a man-made cosmos around us in which we will not have to depend on decorations to render our homes livable, but which will give us an awareness of belonging to a space center and of the ever-present cosmic forces which feed us continuously, nourish us physically, emotionally, and spiritually, without end" ("Notes on Architecture as Sculpture," Art in America 54 no. 3 [May-June 19661, p. 68).

[24] Kiesler cited in Cynthia Goodman's "Frederick Kiesler: Designs for Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery," p. 93.

[25] This logic extends to Kiesler's house designs produced after he moved to the United States in 1926 (he gained citizenship in 1936). His Space House, developed in the U.S. in 1933, would be a "one-space- unit," employing the spherical shape, free plan, and the elimination of interior walls as structural supports. His "shell-monolith" or "egg-shell" structure would overcome the divisive partitionings of "roof, floor, wall or column," suggesting even then the intrauterine yearnings that would generally characterize his work.

[26] "Mathématique sensible–architecture du Temps," Minotaure 11 (Spring 1938), p. 43; translated in Lucy Lippard, Surrealists on Art (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1970), p. 168. Matta trained under Le Corbusier before joining the Surrealists and countering Le Corbusier's rational architecture, where the home existed as a "machine for living."

[27] "D'un certain Automatisme du Goût," Minotaure 3-4 (December 1933). For his condemnation of nationalism and traditional humanist categories, see "Dada Manifesto 1918," in Tristan Tzara, Seven Dada Manifestos, trans. Barbara Wright (New York: Riverrun Press, 1981).

[28] "Le Complexe, Facteur Concret de la Psychologie Familiale," in L’Encyclopédie française, ed. A. de Monzie, vol. 8 (Paris, 1938), p. 8. For a discussion of Lacan's text, see Carolyn Dean, The Self and Its Pleasures (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).

[29] For an alternative view of Kiesler, see Mark Linder's "Wild Kingdom: Frederick Kiesler's Display of the Avant-Garde," in Autonomy and Ideology: Positioning an Avant-Garde in America, ed. R. E. Somol (New York: Monacelli, 1997). Linder treats Kiesler's designs as productive of a subject construction continuous with those found in Lacan's theory of the mirror stage and Caillois's discussion of mimicry. Against this view, I find such a complex subjectivity, marked above all by psychic divisions, completely absent in Kiesler's rhetoric and display constructions, particularly around 1942.