Surrealist Installation as a Labyrinth

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

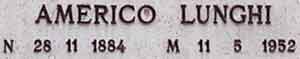

Americo Lunghi (1884-1952) |

Americo Lunghi (1884-1952) |

Surrealist Installation as a Labyrinth

Duchamp's Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942 (Part 1)

T. J. Demos

Duchamp's Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942 (Part 2)*

Duchamp's Labyrinth

Duchamp's installation for First Papers, needless to say, functioned in an altogether different way than Kiesler's design. The string, spanning the gallery in all directions without order or system, produced a space that countered any sense of homeliness. While Kiesler had facilitated Surrealism's mythologization through the fantasy of framelessness and motivated by the experience of dislocation, Duchamp's installation forcefully restored the frame, hindering visual access to the displayed paintings and manifesting a layer of ineluctable mediation between viewer and art object. Instead of undertaking a facilitating role for the consumption of Surrealist art-the traditional function of exhibition design-and rather than "correlating" viewer and art object to the ideal point of their mutual fusion, Duchamp's string produced a recalcitrant barrier between viewers, objects, and space. What was behind this insistence on the frame in 1942? If Kiesler's exhibition design for the Art of This Century Gallery can be seen as a compensatory reaction to the historical reality of geopolitical displacement, then how did Duchamp's installation function in relation to the conditions of exile? Was it just a Dada-influenced nihilistic gesture, or did the string installation act against certain developments in Surrealism, thus complicating the definition of the dislocated avant-garde at this historical moment?

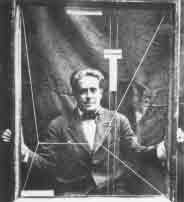

Duchamp; With Hidden Noise, 1916.

One answer comes from Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, who has argued that Duchamp's installation was a direct challenge to the institutionalization of Surrealism and the "quasi-religious veneration of [its] acculturation," as well as a critical assault on the continued but deeply problematic role of painting within Surrealist practice.[30] This was certainly true. During 1942, when First Papers were on display, Duchamp spoke more vociferously than ever about his contempt for painting, criticizing precisely its quasi-religious veneration: "I don't believe in the sacred mission of the painter. My attitude toward art is that of an atheist toward religion. I would rather be shot, kill myself, or kill somebody else, than paint again."[31] And he is reported to have explained that his string installation was "intended" to "combat the background," where "the background” - remaining unspecified-ambiguously suggests both the opulent architectural interior of the Ried mansion and the background of Surrealist paintings that the string obscured.”[32] Duchamp later recalled that he had to "fight . . . some painters [who] were actually disgusted with the idea of having their paintings in back of lines like that, [because they] thought nobody would see their paintings."[33] Others recognized the brutality of this assault as well, with many reviews complaining about the obscurity of the paintings behind the string.[34] Clement Greenberg must have been thinking of Duchamp's string installation when he called Surrealism an "anti-institutional, anti-formal, anti-aesthetic nihilism . . . inherited from Dada with all the artificial nonsense."[35]

However, Buchloh's reading, more an introduction to an interpretation of Marcel Broodthaers's institutional critique than a historicization of Duchamp's installation, leaves unexplored how Duchamp's construction displaced Surrealist practice from other developments: namely, the "return to a habitable world" concurrently undertaken in Breton's myth and in Kiesler's exhibition design. Duchamp's installation offered not just a general de-deification of Surrealism, but contested Kiesler's fantasy of framelessness.[36] Instead of providing an insulating mythological womb protecting against displacement, Duchamp's installation in fact forced artists to experience their displaced status firsthand in the disorganized and disorganizing space of his installation and in the disorientation of their objects in that space. This, in effect, introduced a political framework to a display of art intent on escaping it.

The historically specific political rupture articulated in Duchamp's installation resonates with the double critiques of Surrealism and the home forwarded by Theodor Adorno. Arguing that an aesthetic break in avant-garde practice was necessary due to the war, Adorno observed in 1953 that with "the European catastrophe, the Surrealist shocks lost their force."[37] When he explained that "the dialectical images of Surrealism are images of a dialectic of subjective freedom in a situation of objective unfreedom," this criticism might be redeployed as commenting on the wartime conditions of Surrealism.[38] As we have seen, the movement's increasing political impotence was met with the mythologization of its aesthetics, producing the subjective freedom of a mythical homeliness in a situation of geopolitical homelessness. Duchamp's installation indicates a rupture with this escapist logic and an acknowledgment of displacement, which the Surrealists seemed intent on obfuscating. Adorno also directly criticized the desire for homeliness, declaring in 1944 that "the house is past" (Das Haus ist vergangen) because it had been rendered conceptually impossible due to the devastation of war. The house had become historically unrecognizable after the apocalyptic results of the desperate and fanatical attempts to reclaim the home during the 1930s and '40s. For Adorno, homeliness was rendered impossible not only because of the fascist appropriation or destruction of houses and the genocidal murder of their inhabitants, but also because the very desire for the home had been revealed as destructively nostalgic, irresponsibly regressive, noxiously capitalist and nationalist, and at its worst, fascist (which certainly complements Lacan's view of the regressive and fascist desire for homeliness). Even though the innocently dislocated needed places to live (as Adorno himself did during- the 1930s and '40s), the desire to be at home, comfortable, sheltered, and integrated, was seen as an irresponsible abstraction and an apolitical impulse that could only represent a "betrayal of knowledge." This betrayal refers to the willful ignorance of political consciousness and the disregard for the reality of displacement that would conflict with homely regression. Thus, Adorno would claim: "Today we should have to add: it is part of morality not to be at home in one's home."[39] It is precisely because the home became overdetermined by fascism, where nationalism defined itself through psycho-social-architectural fusion, that the fragmentary space and dislocated status of objects within Duchamp's installation become politically meaningful and subversive. And it is because of this overdetermination of the homely as fascist that any architecture of fusion became suspect as a utopian project and historically displaced as an avant-garde model of exhibition space.

Francis Picabia; Dance Saint-Guy, 1920-21.

Duchamp's installation accomplished the subversion of Surrealist homeliness by constructing a disorienting frame. This frame prohibited any pretensions regarding an unmediated unity between viewers and art objects. It is important to recognize, in exploring the installation as a frame, that it shares in the logic of the readymade.[40] We can easily trace the development of string from readymade to frame in the earlier twentieth century. String had appeared in Duchamp's work as a compositional element in Chocolate Grinder (1914), representing the divisions between the slats of the three barrels. Isolated, it was employed in Three Standard Stoppages of 1913, where the recordings of three variations of one meter of string fallen on the ground, attached to Plexiglas supports, were enclosed in a croquet box. Soon, string moved from compositional element to container in With Hidden Noise of 1916, where a readymade ball of twine enclosed in two copper plates, screwed together, concealed a secret object unknown to Duchamp. The use of string as a frame was also employed by Duchamp's friend Francis Picabia. In his 1920-21 Dance de Saint-Guy, string was stretched within a readymade frame for an easel painting and suspended paper cards with handwritten text.[41] Picabia's construction advanced the readymade toward the internalization of institutional conventions within its very structure. Just as Dance de Saint-Guy displays its miniature "pictures" within its frame, the construction mimics the common convention of hanging paintings by string or wire from wall moldings.

These objects clearly participate in the Dada assault on the integrity of the art object by substituting a frame in its place. By negating the picture's visual status, they shift from an artistic model based on artisanal creativity and authorial expression to one that focuses on its own institutional determination by offering a frame for analysis rather than an object for aesthetic contemplation. They also indicate the early avant-garde realization that frames as such exist as an unavoidable- even readymade-mediation in the reception and consumption of works of art.

Marcel Duchamp; Sculpture for Traveling, 1918.

But Picabia's Dance also demonstrates a sensitivity to mobility, due to its transparent form that establishes a contingency on context. Developed in a period of itinerant travel during the war, Picabia's work follows on the heels of Duchamp's Sculpture for Traveling of 1918, which Duchamp carried with him to Buenos Aires during his own flight from the nationalism of Europe and Arnerica.[42] The Sculpture for Traveling, composed of fragments of readymade rubber shower caps cut up and glued back together as strands of varied lengths, would adapt its format to each new installation. "The form was ad libitum," Duchamp explained to Cabanne. The readymade, then, was already diversified as an artistic model during World War I. It became more than the structural critiques of the author, object, and institution. Stressing collapsibility, portability, and contextual determination, the readymade established a relationship with geopolitical displacement.[43]

Similarly, the installation for First Papers-also a readymade string frame–was not merely an outgrowth of a structural account of the readymade (which would see in it the critical debunking of the traditional concepts of originality, authorial agency and intentionality, and the proposal of new framing conventions and collaborative conditions for the art object). Rather, it developed out of an earlier Dadaist concern for mobility and postnational conditions, but also takes a step further. The insistent, disorganizing spatial conditions of the string acted on the space around it, interrupting the contemplation of Surrealist paintings. By the domination of that space, the installation enforced a set of disorienting conditions on the gallery space that were summarized by the word "labyrinth" in nearly every review of the exhibition. Through this labyrinthine installation, which extends out from the readymade's relation to dislocation, Duchamp constructed a homeless space sensitive to geopolitical displacement and one that negated Surrealist homeliness.

Matta; The Onyx of Electra, 1944.

It may seem paradoxical to read Duchamp's installation as simultaneously labyrinthine and a negation of Surrealism; for if it acted as a labyrinth, then it drew on a quintessential Surrealist trope. The labyrinth and its counterpart, the Minotaur, had variously served as subjects of Surrealist work throughout the 1930s and early '40s. And Minotaure, of course, was the title of a Surrealist journal from 1933 to 1939. Various covers of the journal, showing Minotaurs and labyrinths, were designed by many artists, including Duchamp.[44] In addition, Georges Bataille had recently written the essay "The Labyrinth" in 1936. Rut while the labyrinth dominated the Surrealist imagination during the 1930s, its meaning or use was no more fixed than was Surrealism. And nothing suggests that reading Duchamp's installation as labyrinthine necessarily entails the affirmation of Surrealist aesthetics in general or even its specific directions in 1942. Nevertheless, art historians have consistently read the installation as continuous with Surrealist art and its common figure of the labyrinth, which discourages the view that the installation instead challenged Surrealism.[45] Such a thesis, however, depends upon a number of objectionable comparisons and problematic underlying assumptions.

Some historians, for instance, have gone to extremes in comparing the structure of the installation to that of painting. William Rubin, for instance, likens the string installation to a labyrinth and then proceeds to associate it with pictorial organization. Incredibly, at one point Rubin virtually collapses the string installation with Matta's matrix-like paintings, explaining that its "spatial effects . . . were later explored by Matta in such paintings as Onyx of Electra and Xpace and the Ego . . . [which create] a vertiginous environment . . . in deep perspective space."[46] In other words, Rubin dissembles the fact that the string, hung in its haphazard manner, confused spatial relationships, created its own intricate and asystematic patterns without any intelligible plan, and existed beyond pictorial rationalization. As a physical barrier to depth, Duchamp's string countered perspective, which organizes space and renders it perceptual as depth. Its own lack of compositional or perspectival logic assaulted the visual mastery and centering functions associated with perspective (as in Matta's paintings), which is normally facilitated by frames, whether they be the frames of paintings or the larger architectural frames around paintings.

Additionally, Duchamp's installation challenged the psychological depth of Matta's expressionist aesthetics built upon that perspective. Matta frequently explained that his paintings developed "a morphological projection of a psychological state." Duchamp's installation, on the other hand, refused any intentional psychic content or metaphysics of interiority. Rather, it set up the conditions for a physical and conceptual experience wholly transpiring during the visitor's interaction within it. Its logic, instead of being representative or expressive, was performative, blocking any immersion within the displayed paintings. This performative aspect no doubt continued the logic of the readymade, necessitating the viewer's participation in the creation of meaning.[47] By forcing viewers to struggle to see the work through the string, which physically interfered with their bodily space, it brought what was the readymade's collaborative conceptual act in interpretation to a physical level. If, in 1957, Duchamp famously dismissed the creative model where ". . . the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing," then he appears to have combated that creative model by inserting the viewer within his own version of a labyrinthine frame in 1942.[48] Not only do these readings of First Papers appear to contradict the form and function of Duchamp's installation, but they also plainly fail to take account of the radicality of the labyrinthine structure that they so often cite as an explanatory model (just as they fail to examine the structure of the redefined readymade). By aestheticizing the labyrinth, comparing it to the organizing and rationalizing spatial matrix of perspective, and viewing it as a means for psychological expression and intentional meaning, these readings end up vulgarizing and even dehistoricizing this potentially powerful conceptual complex.

Marcel Duchamp; La Boîte-en -valise, 1935-41.

The fully radicalized elements of the labyrinth were explored by Georges Bataille in his 1936 essay "The Labyrinth," to which none of the conventional views of Duchamp's installation refer. The labyrinth, in Bataille's version, describes a disorienting ontological and epistemological model of identity, structure, and space, in which all are radically decentered. But the labyrinth also resonates with the specific historical period of national deracination and foreign invasion. The period around 1936 coincided with the end of Bataille's participation in the politics of Contre-Attaque and with all of the frustrations that accompanied the ineffectuality of an oppositional, antinational political practice at the time. If Bataille, in Contre-Attaque, organized under a politics of homelessness, then he also imagined its theoretical site: the labyrinth. But it wasn't merely theoretical and it certainly wasn't the mythological place to which Breton retreated; rather, the labyrinth represented a disoriented Europe in the late 1930s and early '40s. The labyrinth, then, was both part of a dialectical account of space and identity (along with its oppositional term, "architecture” –the name for structure, logic, and state authority)[49] as well as a designator for a historically specific set of conditions and experiences relating to dislocation.[50]

Bataille's labyrinth identifies a structure that is against structure itself, an anti-architecture that counters systematicity. The essay begins with a discussion of the "negativity" of being, quoting Hegel to this effect in its epigraph: "Negativity, in other words, the integrity of determination." This negativity occurs in spatial terms, or against spatial terms, in that, in the labyrinth, being has no positive place-it is determined, rather, by its negativity. And it redefines the ontological status of being as relative, contingent, and without secure location. It exists, rather, between locations. "Being" thus takes on a "fugitive appearance," compared to the disorientation in a "labyrinth where what had suddenly come forward strangely loses its way."[51] The labyrinth also operates linguistically. The relativity of being is evidenced by its contingency upon language: "Each person can only represent his total existence . . . through the medium of words. ... Being depends on the mediation of words," notes Bataille. As a place of radical contingency rather than a matrix of coherent space, the labyrinth, then, refers to a continually shifting materialization of the nebulous network between the mutually determined terms of language and identity-in effect, a complex frame in which being is irrevocably situated. Spatial, psychic, and linguistic, the labyrinth names a place of dislocation where all is submitted to an utter contingency upon its decentering frame. Being evokes "a kind of nausea" because "being is in fact nowhere" –an apt characterization for labyrinthine experience.

Bataille's essay parallels the realizations of contemporaneous philosophical and theoretical developments. It acknowledges the fundamental tenet of structural linguistics regarding the absence of the positivity of meaning due to the differential structure of signs. And it agrees with the subjective impossibility of total self-consciousness, or the mastery of the visual field, articulated in psychoanalytic theory. But the "nausea" of the labyrinth also identifies the experience of the loss or threatened loss of nation-state identity and consequent dislocation, described as such by many who encountered it in the late 1930s.[52] As Denis Hollier observes in his reading of Bataille's text: "War, a primary form of ignorance about the future, entails first of all the suspension of plans. A catalyst of anguish, war condemns human beings to the irremediable disorientation of the labyrinth, to a glorious intoxication in the face of life's incompleteness."[53]

Such a logic, simultaneously bearing on structure, identity, and dislocation, approaches that of Duchamp's installation, which acted as such a labyrinth, as a de-structuring anti-architecture producing contingent identity, lost meaning, and disorienting space. The installation was not a labyrinth merely because it looked like one; it was labyrinthine because it displaced space, viewers, and objects alike.

Such a displacement occurred when the installation came to frame Surrealist paintings, including Matta's Great Transparents, which exemplified the desire to return to a state of habitability according to Breton's myth. Radicalizing the readymade installation as performative, its significance was located in what it did. By filling in the negative space between works of art and viewers, causing a rupture in reception, the string redirected attention toward the frame and away from the possibilities of a unified aesthetic experience. Forcing viewers to look through string, or to move it aside in order to see a work of art, it eliminated any possibility of "fusing" with objects or space in a psychophysiological way, as Kiesler proposed in his installation. By reasserting the frame, any conception of the art object as ideal, immanent, or autonomous was negated. Duchamp's installation would thus encourage viewers to consider the significance of the physical context and their own participation in the production or experience of any meaning in the encounter with art objects. Consequently, the installation would combat the mythologizing and idealizing impulses within Surrealist aesthetics by rendering the meaning of its objects contingent upon frames and viewers.

Duchamp's installation can also be seen to have functioned as a linguistic frame, occupying the spacing between works, emphasizing their contingency, like the differential and "related" structure of words. Bataille noted, "One need only follow, for a short time, the traces of the repeated circuits of words to discover, in a disconcerting vision, the labyrinthine structure of the human being."[54] The installation, rather than being literally linguistic, performed this by tracking the mediating "circuits" between individual objects and viewers, which the string occupied. This forced a sensitivity to the spaces between artworks and thus obliterated the neutrality or ideality of the art objects, rendering them instead "related beings." In other words, the string revealed the "labyrinthine structure" of mediation between objects, spaces, and viewers.[55] In so doing, it multiplied meanings and ruined immanence. In this sense too, Duchamp's string articulated the readymade structure of the labyrinth. As the matrix of language is understood by Bataille to be a precondition of being, an already existing system of rules, grammar, and syntax that is constitutive of meaning and subjectivity, then the string installation spatialized this readymade frame. By enlarging the readymade string to architectural proportions, this structural determination of meaning, subjectivity, and space was revealed to be institutional as well as linguistic and phenomenological.

If the installation dislocated objects within its purview, rendering them "homeless" in a way, then this effect may have been a result of the string's logic as a readymade. Rosalind Krauss has explained that the readymade exposes the "homelessness" of modernism due to its necessary disconnection from its original context and its consequent mobility. The readymade thus enters what Krauss calls "the space . . . of sitelessness, or homelessness, an absolute loss of place. Which is to say one enters modernism? ..."[56] Similarly, the string frame, in becoming readymade, produced a kind of homeless space-not only in terms of its own mobility (moved from store to gallery), but rather that, within it, space and objects were dislocated, and thus the inevitable condition of exhibition was revealed as displacement. As a readymade frame it extended its homeless status to objects caught in its web, like a labyrinth. In this respect, we encounter a development from modernist homelessness to political homelessness in moving from the earlier readymade to the readymade frame of 1942.[57] While earlier readymades revealed the mobility and exhibition-based identity of the art object in its modern condition, the string installation became political in that it fought the reactionary mythologization of objects that wanted to exist in a frameless homeliness-objects which it consequently framed. There, a political event occurred when the installation physically assaulted other objects and insisted on the condition of "not being at home in one's home," as Adorno's political homelessness would have it.

The installation, then, operated in a number of interrelated ways. It offered an ontological critique of its displayed objects, challenging the structural possibilities of a "frameless" aesthetic space or a fusional experience of paintings. Its stubbornness as a physical barrier refused the Surrealist impulse to suppress the signs of the gallery. This amounted to a contestation of how an installation (and Kiesler's in specific) might otherwise negotiate the avant-garde's contradictions (its anti-institutional, anticapitalist ideology versus its acculturation and commodification) by obfuscating them through the construction of a highly artificial exhibition design. On the contrary, Duchamp's installation both negated the traditional gallery's functions (the neutral exhibition of works of art) and concretized the institution's presence as an inevitable readymade frame. Lastly, Duchamp's installation operated as part of an insistent homeless aesthetic that negotiated geopolitical displacement. It combated the movement of Surrealism in exile toward a compensatory mythologization and search for habitable space. Its labyrinthine frame challenged the homely developments that occurred in Surrealist ideology, aesthetics, and installation techniques in 1942.

The installation for First Papers was certainly not a unique example of Duchamp's development of a homeless aesthetic. It was instead part of a larger engagement motivated by antinationalism, and concretized through modernist strategies. This included his nomadic "portable museum," La Boîte-en-valise of 1935-41, and his disorienting installation of 1,200 coal sacks for the Surrealist exhibition in Paris in 1938. Both of these projects evince a pressing concern with frames and borders, a sensitivity to restricted space and controlled movement, and an emphasis on the instability of placement and the uprooting effects of decontextualization.[58] Ultimately, such a sensitivity must be seen to reverberate with the geopolitical dislocation Duchamp lived, perhaps in the most extreme circumstances during 1940-42, when he circulated in and out of occupied France and then to New York. "I left France during the war, in 1942," Duchamp explained, "when I would have had to have been part of the Resistance. I don't have what is called a strong patriotic sense; I'd rather not even talk about it."59 Yet if Duchamp didn't want to talk about it, his work certainly did, and his lack of patriotism during these wartime years extended to the artistic refusal of even the most seemingly innocuous security of space or homely comfort.

* T. J. Demos; Duchamp's Labyrinth: "First Papers of Surrealism", 1942 - October, Vol. 97. Summer, 2001, pp. 106-119.

Notes

[30] Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, "The Museum Fictions of Marcel Broodthaers," in Museums Artists, ed. A. A. Bronson and Peggy Gale (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1983), p. 46.

[31] "Artist at Ease," The New Yorker 18 (October 24, 1942), p. 13.

[32] "Agonized Humor," Newsweek 20 (October 26, 1942), p. 76.

[33] Harriet and Carroll Janis, interview with Marcel Duchamp, winter 1953, typescript, Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives, pp. 7-16; cited in Kachur, p. 226.

[34] For example, "The Passing Shows," Art News 41 (November 1, 1942); and Royal Cortissoz, "George Bellows and Some Others," New York Herald Tribune (October 25, 1942), section VI, p. 5.

[35] "Surrealist Painting," The Nation 12 and 19 (August 1944) ;reprinted in Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O'Brlan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986),vol. 1, p. 225.

[36] Duchamp later spoke of "de-deifying everything by more materialistic thoughts" in the interview with Francis Roberts, saying " I propose to strain the laws of physics," Art News 67 (December 1968),p. 47.

[37] "Looking Back on Surrealism," in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), p. 87. This corresponded to Duchamp's view in 1936 when he understood the existing political conditions to necessitate an aesthetic withdrawal: "Painting is now dedicated the world over to propaganda-to subject matter. . . . It is as true in Europe as in America-even more so-that people's minds are concentrated on politics, including the artists. Both Fascism and Communism are bent on regimenting people, robbing them of their individuality. It is no atmosphere in which creative art can thrive." Interview with C. J. Bulliet for the Chicago Daily News, cited in Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy," in Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, ed. Pontus Hulten (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993), under August 25, 1936.

[38] Adorno, p. 88.

[39] Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life (1951), trans. E. F. N. Jephcott (New York: Verso, 1991), no. 18, pp. 38-39 (my emphasis).

[40] The string was purchased by Duchamp, who explained in the interview with Janis, "I had a friend, even almost a relative, in Boston who is an accountant in a cordage place for Boston Harbor. And he sold me that 16 miles of string-it was a regular business."

[41] William Camfield explains that Dance de Saint-Guy was refashioned as Tabac-Rat sometime before 1949. Picabia insisted that this object be suspended away from the wall to stress its transparency. Camfield also points out that these constructions were related to Picabia's "stage designs" at the Manifestation Dada of March 27, 1920, where he stretched cords across the stage in front of the performers. See Camfield's Francis Picabia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), p. 172.

[42] Duchamp explained to Pierre Cabanne that in 1918 "I left for a neutral country. You know, since 1917 America had been in the war, and I had left France basically for lack of militarism. . . . [But] I had fallen into American patriotism, which certainly was worse. . . . I left in June-July 1918, to find a neutral country called Argentina" (Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp [New York: Viking, 19711, p. 59).

[43] This earlier context of dislocation certainly requires further examination, but beyond the scope of this essay.

[44] Duchamp's Minotaure guards the back cover of issue no. 6 (December 1934).

[45] For example, Marcel Jean reads the installation as "an immense 'spider's web' made of miles of white twine stretched across the rooms, an aerial labyrinth criss-crossing at every angle" (The History of Surrealist Painting [New York: Grove, 19601, p. 312). And according to William Rubin, "Duchamp designed the installation, which consisted of a mile of string, an Ariadne's thread beyond which the pictures hung like secrets at the heart of a labyrinth" (Dada and Surrealism and their Heritage, New York: Museum of' Modern Art, 1968, p. 160).

[46] Rubin, Dada und Surrealism, composite quotation from pp. 160 and 169. Romy Golan, in "Matta, Duchamp et le Myth: un Nouveau Paradigm pour la derniére phase du Surréalisme" in Matta (Paris: Pompidou, 1985), also relates the perspectival space of Matta's The Onyx of Electra of 1944 to Duchamp's string. Sabine Eckmann again rehearses this reading: "Duchamp's labyrinthine twine installation . . . and the same artist's 'Large Glass,' . . . inspired Matta to use these lines to suggest multi-perspectival spatial systems." See her "Surrealism in Exile: Responses to the European Destruction of Humanism," in Exiles and Emigrés, pp. 179-80.

[47] Benjamin H. D. Buchloh has suggested that the readymade is quintessentially a collaborative act in "Readymade, Objet Trouvé, Idée Reçue," in Dissent: The Issue of Modern Art (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1985), p. 107.

[48] Duchamp delivered "The Creative Act" in Houston at the meeting of the American Federation of the Arts, April 1957. It is reprinted in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York: Da Capo, 1973), pp. 139-40.

[49] Bataille's "Critical Dictionary" contains an entry for "Architecture," which, for its author, expresses the authority of church and state. Originally published in Documents 2 (May 1929), it is translated by Dominic Faccini, in October 60 (Spring 1992). On Bataille and architecture, see Denis Hollier, Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, trans. Betsy Wing (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989).

[50] Bataille also moved from an action-oriented politics of homelessness, once its impotence became evident, toward mysticism and ritual in the later 1930s. This was defined by his shift from Contre-Attaque to the esoteric and secretive activities of Acéphale in 1936 and then to Le Collège de Sociologie during 1937-39. However, Bataille's mysticism, very different than Breton's, was directed toward a space of interiority alternating between castration and virility, opening sexuality to politics, and identity to a splitting violence. See Susan Suleiman, who argues that Bataille repositioned activism within myth and ritual, both paradoxical and productive, in "Bataille in the Street: The Search for Virility in the 1930s," in Bataille: Writing the Sacred, ed. Carolyn Bailey Gill (New York: Routledge, 1995). For Denis Hollier, Bataille's was a literary equivocation that was itself deeply political. See "On Equivocation between Literature and Politics," Absent without Leave, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997).

[51] Bataille, "The Labyrinth," in Visions of Excess, p. 173; first published in Recherches philosophiques 5 (1933-36).

[52] Walter Benjamin, for example, frequently described his experience of exile in very physical terms. For instance, by 1938, living in Paris, disaffected from his national home, and suffering from economic hardship and the anomie of exile, Benjamin characterized his situation "as a man at home between the jaws of a crocodile which he holds apart with iron struts." Cited in Susan Buck-Morss, Origin of Negative Dialectics (Hassocks, Sussex: Harvester, 1977), p. 155.

[53] Hollier, "Unsatisfied Desire," in Absent Without Leave, p. 70.

[54] Bataille, "The Labyrinth," p. 174. Hollier further notes: "The labyrinth does not hold still, hut because of its unbounded nature breaks open lexical prisons, prevents any word from finding a resting place ever, from resting in some arrested meaning, forces them into metamorphoses where their meaning is lost, or at least put at risk. It reintroduces the action of schizogenesis into lexical space, multiplying meanings by inverting and splitting them: it makes words drunk" (Against Architecture, p. 60).

[55] What Derrida would call the "spacings" between words and pages that are necessary for their meaningful differentiation. On the structural conditions of the frame, see Jacques Derrida, "Parergon," in The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978).

[56] Rosalind Krauss, "Sculpture in the Expanded Field," The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989), p. 280.

[57] Even though the earlier model of the readymade, like Duchamp's Sculpture for Traveling, already proposes such a development in the relation between mobility and postnationalism that it sets up.

[58] I explore these projects in depth in a book-length study of Duchamp and postnationalism currently under preparation.