Duchamp Game of Large Glass

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Guido Bordichini (1925-1984) |

Guido Bordichini (1925-1984) |

Duchamp Game of Large Glass

Lawrence D. Steefel, Jr.

Marcel Duchamp and the Machine*

To insist on purity is to baptize instinct, to humanize art, and to deify personality.

Artists are above all men who want to become inhuman.

Guillaume Apollinaire, 1913Mallarme was a great figure. This is the direction in which art should turn: to an intellectual expression rather than to an animal expression. I am sick of the expression "béte comme on peintre" –stupid as a painter.

Marcel Duchamp, 1946

Marcel Duchamp’s interest in the machine and the mechanistic is best understood as a consequence of his pursuit of a poetic of impersonality in which there will be a positive separation for the artist between "the man who suffers and the mind that creates."[1] Seeking to distance himself from his own fantasies, Duchamp sought a means of converting pathos into pleasure and emotion into thought. His mechanism of conversion was a strange one, but essentially it consisted of inventing a "displacement game" that would project conflicts and distill excitements into surrogate objects and constructs without whose existence his mental equilibrium might not have been sustained. Using personalized though expressively impersonal conventions drawn from what Elizabeth Sewell has called "the field of nonsense," Duchamp disciplined the artistic products of his excited fantasy by a progressive mechanization of their aesthetic valence. By using the machine as an increasingly distinct and rigid counter against the turbulent vastness of unchanneled association and unfiltered dream, Duchamp created an art of nonsense that "hygienically" freed his mind from all those capsizing factors which had previously haunted him as a Laforguian "sad young man."[2]

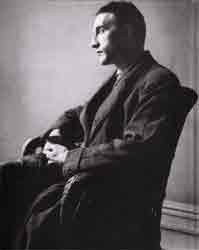

Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1916.

Framing the oppositions and conjugations of his fantasy into the provocative perplexes of a hallucinogenic art, Duchamp, "like a mediumistic being, who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing," manages to work his way out to a position where the "blankness of dada" and the power of invention paradoxically coincide.[3] Viewed as problematic outcomes of Duchamp's struggle against obsessional impulses and fantasies in himself, the mechanomorphic works of 1911-12 and the machine works after that, as compared to his earlier productions, seem both tamer and more dangerous. Like appanages or autonomous dependencies subject to the sovereignty though not the full possession of Duchamp's conscious self, these works are full of aggressive irrationality beneath their apparent nonchalance.

Leading us, the viewers, back toward the condition from which Duchamp had originally worked himself out, images like Nude Descending a Stair-case, The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride, and Readymades like the Bicycle Wheel, With Hidden Noise, or In Advance o f the Broken Arm frustrate our good intentions and insult our common sense. Framed as they are by a superficially logical set of titles to be correlated with what ought to, but does not, make sense, Duchamp's visual puzzles lead us to expect that with sufficient effort and technical intelligence we can integrate his problems by sheer persistency of task. If we can only transcend his inconsistencies by extrapolating his consistencies, or so we fondly think, we can master the situation and find ourselves at rest. For most if not all viewers, however, this is a deceptive and irrational hope, for the ultimate heuristic thrust of Duchamp's dissembling work is to lead us continually to a brink of consummatory expectation only to "shortcircuit" our cognitive grasp.[4]

By demonically distributing complex clues of representational deception and an abstract pattern that is never quite "abstract," Duchamp makes sure that his refractory productions frustrate their own illusions of integrity by being neither true nor false except to their own rationale of divisive anamorphism and self-reflexive plot. As counters in the Duchamp game, which is a displacement game par excellence, his works are both too consistent to be wholly inconsistent and too inconsistent to be wholly consistent, leaving us, the viewers, either the uncomfortable option of endlessly inventing new rules for the game as we pursue its play or the bewildering option of lapsing into delighted (or not so delighted) indifference as to what it is we play. Since most viewers will be oriented, as Duchamp originally was, to dominance in the Duchamp game, one can only persist in seeking devices for shortcircuiting difficulty, or adopt (as Duchamp did) what he called a posture of "meta-irony," an affirmative indifference to irresolution and difficulty which accepts ambiguity as normative and the problematical as "nonsense."[5] But here we are at the heart of the matter!

It is only in Duchamp's first machine image, the Coffee Mill of 1911, that an achievable possibility of perceptually short-circuiting the built-in contradictions of the imagery surely exists for us. In all subsequent cases, the mentalité of meta-irony, with its "nonsense" strategy of playfully accepting what one cannot otherwise outplay, seems the only alternative to being blocked or else "debrained" by Duchamp's cruel cervellites.[6] In the Coffee Mill we see an object of passive manipulation transformed into a mechanism apparently operating under its own power. Something potentially autonomous is thus derived from a culinary banality. Painted ostensibly as a wedding gift for his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon ("Every kitchen needs a coffee grinder, so here is one from me"), this small panel is a kind of premonitory manifesto of what Duchamp himself turned out to be: a freewheeling operative of elusive inconsistency whose motion in space and time was centered on himself in an effort to transcend his origins as a provincial bourgeois notaire's son and the existential burden of what he called physicality. By physicality he meant the whole mess of contingent interests and necessities one suffers by having a body and being part of society. If one could escape being acted upon by forces beyond one's own powers of self-motivation and self-mastery, as the little machine seems to have done, then one could, like the machine, focus on one's "head" and blossom into "pure operation" of blissful motility. Significantly, one can construct such a blossoming in the handle complex of the Coffee Mill only by mastering a technique of looking "beyond" the thrashing handle positions to the orbit of perfect enclosure that is imperfectly rendered by Duchamp. This orbit, formed of a circle of dots culminating in a curved arrow of directed constancy, must be converted by the viewer into a field of virtual motion and spatialized lubricity ; if this can be done, the machine becomes a glimpse of freedom as pure mentality. This mentality is an apparitional presence of sheer immediacy which is visual insofar as we see it spatially but is intuitive insofar as we appreciate it as a resolution of a perceptual difficulty encountered in scanning the image syntactically and semantically.[7]

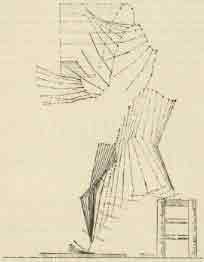

E. J. Marey, Jump from a height with stiffened legs, from his book Movement, translated by Eric Pritchard (London: William Heinemann, 1895).

Painted in a polyglot style of Cubist and quasi-Futurist elements with just enough "realism" to tempt us toward believing the image is of a real machine, Duchamp's panel combines static and dynamic patterns in a subtle and devious way, so that we are both attracted by the lack of inertial "frictions" and bothered by what we see. What bothers us is lack of purposefulness in an image of such intricacy, and we may also be distracted by the confusion of handle positions within the orbit that contains their sweep. These multiple handle options do not behave consistently. Some are horizontal, some are vertical, and some wobble crazily. Out of this turbulence one seeks a resolution of representational or postural consistency, but it is only by "going beyond" their thrashing that one can find perceptual serenity.[8]

In this image one can, I believe, go beyond physical impediments to imaginative consistency, but this is the only image in Duchamp's oeuvre where one can "go beyond" literally. In all his other images, even those like the Large Glass, where there is a perspective system with a vanishing point at infinity, "going into depth" is ultimately a fruitless effort if one is to find serenity. Only by accepting the necessity of a "blocked depth" or an internal échec in trying to "see through" Duchamp's work can one achieve the ataraxia of detachment from his problems (that is, from both Duchamp's and ours). One must either welcome the hypnotizing of our attention that Duchamp's paradoxes evoke or force oneself to become detached from them as Duchamp gradually did.

The method of detachment involved an increasing reliance on the machine as a target for his interest in letting himself he free from troubling obsessions (whatever their nature) and personal passions (whatever those might be). As Duchamp once said to me, “I did not really love the machine," adding, "It was better to do it to machines than to people, or doing it to me.”[9] By letting machines and mechanisms suffer outrageously, Duchamp could muster his energies for survival and the pursuit of poetry. Duchamp's poetic was basically Mallarmean, with a strong dose of irony ; hence it was a poetic of mental freedom and creative autonomy.[10] He willingly called himself on aspirateur once he gave up painting consistently (a wonderful pun combining the sense of aspirateur as "vacuum cleaner" and also as "free breather" of personal autonomy), and the idea of breath is linked to both "inspiration" and "coming to life" be-yond the limits of mechanization or the bounds of determinacy.[11] One can see the process of detachment beginning to operate in Nude Descending a Staircase, internally within the image as well as externally in the necessity of becoming free from the hope of resolving the image into pure motility.[12]

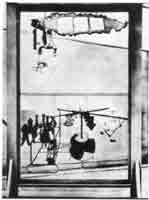

Marcel Duchamp; The Large Glass in its unbroken state at the International Exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. November 19, 1926-January 9, 1927.

In Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912, Duchamp reverses the feeling of passivity conveyed by his first image of a robot person, Sad Young Man in a Train, 1911. The Sad Young Man, which Duchamp has identified as an image of himself in a gloomy mood on a train trip home from Paris, is a sensitive and rather mysterious image of reverberative fantasy. Without stressing its probably sexual overtones, one can believe that Duchamp painted it in a "state of anesthesia." There is something ominous in the work-muted by the subtle color and tonal play, but there nonetheless-as if the artist were submitting himself to a suspension of will as he passes through time. Whether or not one actually perceives a vague but threatening figure behind the serially eclipsed "patient," a phantom who seems to be striking a blow at the "young man's" head, there is still an inescapable sense of fatality and violence in this poignant work that cannot be allayed.[13]

In Nude Descending a Staircase, the persona of the nude actively descends the stairs. Using the stroboscopic effect of chronophotography, especially that developed many years before by E.-J. Marey in the hope of finding a universal language of graphic recordings for movements that are too rapid or too subtle for the unaided eye to catch, Duchamp suffuses a mechanistic shell of postural positions with a fleshy glow of android life[14] evoking not only a traversal of space but also a finesse of locomotion that provokes a sense of body image half-purposeful, halfsomnambulistic, Duchamp dialectically interplays a precision of mechanism with a strangely unpredictable sense of events.[15]

Descending out of a multiple reverberation of swinging phantom states, the nude careens and coalesces in a complex, jostling sweep toward an unknown step we cannot see. Whether the nude will collapse or continue is uncertain. We know of two previous studies of the nude: Once More to This Star (Encore a cet astre), a strangely symptomatic drawing of November 1911; and Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1, a lumpy, nucleated oil of December 1911. In comparison, the definitive version is more serene in its aspects of passage and flow, and more pointed in its malaise (note the depressed carapace head just as it is about to pass the ball-headed newel post at the lower right-hand margin of the frame). While attending to the dynamic enigma of the descent and, perhaps, to the presence or nonpresence of the nude as "nude," we can hardly fail to feel a sense of destiny, however obscure, in the work.[16] As we scan the bewildering profusion of elisions and interruptions, dissolutions and materializations, fragmentations and integrations out of which Duchamp has evolved his "nude descending," this intricacy, which is both the nude and its descent, becomes the ground of a haunting invitation to lose ourselves in the intimate life of the forms. Following this invitation, we are then rebuffed by inconsistencies and refractory elements in the flow and, more importantly, by the nude's coldness and distanced "absence" a la Roussel or Mallarme.[17]

Marcel Duchamp around a Table, New York, 1917.

The "intimacy" of the nude is its most closely guarded secret. Its labyrinthine mystery involves more than the mere recording of space traversal or a game of cherchez la femme, neither of which was of really visceral importance to Duchamp. Rather, this image intimates both a rush of desperation and an ecstasy of hope refracted through a web of glazed impersonality, as if Duchamp had hypostatized his struggles with solipsism into a mechanism of oneiric un-self-consciousness that turns inward to itself.[18] More subtle than a mere projection of feeling into a surrogate persona, yet less articulate than a truly personal expressive form, the Nude, as a total experience, seems both impotent and powerful–impotent in its jeering aspects of mechanized awkwardness and powerful in its freedom of accelerative poise. Since we cannot wholly reduce this image either to pure fantasy or to pure fact, the motivational ambiguity of Duchamp's art becomes an enigma whose symptomology of practice and intent evades our grasp just as the nude as "nude" does.[19]

The Nude, in most ways, was also a mystery to Duchamp. He considered it the unpredictable product of a process which, beginning with a specific technical intent, became something more than what the artist planned. "Between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed" is a coefficient of displacement and "objective chance." ("My chance is different from your chance," said Duchamp.)[20] This differential, which may be "good" chance or "bad" chance, is one of Duchamp's metaphors for both opportunity and fate, a force he denied but with which he was incessantly engaged in a battle of inputs and outcomes one feels was the true locus of his work.[21]

If the machine as "order" was a factor in balancing out personal ineptness, whether of the mind or of the flesh, it was an ambivalent order with overtones of determinism and distress at the same time that it was a way of articulating and displacing that distress.[22] Walking a delicate line between pessimism and hope, Duchamp's Nude seeks an equilibrium, however precarious, that will reconcile destructive and constructive forces, or at least hold them in suspension. Working, in the creative process, through a "series of efforts, pains, satisfactions, refusals, decisions which... cannot and must not be fully self-conscious, at least on the aesthetic plane," the artist pursues an image testifying to a separation between "the man who suffers and the mind that creates." But he will accept, as he must, a provisional limitation to total separation (which for him would be total success). He permits an interplay, at this point in his career, of dream-sense and non-sense with aesthetic finesse-an amalgam of components he would, after 1912, try to reject.[23] If Duchamp's images as expressive compounds behave like thematic apperception tests that do not "appercept," "continuously collapsing into unknown intentions" that frustrate and bother us,[24] Duchamp's mechanization of their "actions" numbs the rawness of their impact by masking and distributing the brute energies of their semantic substrate into and through mechanisms and mechanistic forms that are objectifying and arbitrary if not really "abstract."

In the mechanomorphic period which follows Duchamp's first introjection of mechanical and machinelike "substances" into the "body" of his art, we find a significant intensification of formal concentration matched by a growing sense of distance between our emotional reactions to the forms and to what the imagery is presumably "about." To a crucial extent, for the viewer who becomes involved with Duchamp's imagery of 1912, which mechanizes the body more strictly as it becomes more visceral and abstract, the problem of what the machine means to Duchamp becomes of less immediate interest than the problem of coping with the perceptual and conceptual paradoxes of "seeing" the art. Duchamp's "perplexes" of the year 1912 are pervaded by mechanization and machine forms (mostly armored turret forms and thrashing rotor mechanisms in The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, anatomized filaments and robotoids in The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride, and cruciblelike distillery apparatus in the Bride). It is the labyrinthine elaboration of these mechanisms, more than their "actions," that compels our attention and dazzles our minds.[25] Closer in potential affect to the language labyrinths of Jean-Pierre Brisset, with their elaboration of animal cries into human language, than to any other non- Duchampian verbal or pictorial form,[26] Duchamp's "putting to the question" of parental authority (The King and Queen), the loss of virginity (The Passage) and the matrix (literally "womb") of desire (the Bride) combines an aggressive and regressive obsession with the complexity of primal energies and relationships and a ruthless distancing of interest about these most intimate affairs.[27]

Insofar as "putting to the question" implies both a form of judicial torture and a kind of scientific experiment, Duchamp subjects these intimate concerns to a tortuous discipline of brilliantly composed and succinctly articulated pictorial illusions, full of salient entanglements and provocative interactions and elusive relationships. Condensing hostility into an intricate panoply of esoteric metastatic form, Duchamp makes the human body "humanoid" without resorting to the banal robot structures of conventional science fiction. Thanks largely to his pictorial imagination (a quality he would convert into a mechanic's ingenuity at the end of 1912), Duchamp evolved a strategy of converting Cubist dislocations, detachments, interpenetrations, and figural eclipses into an ambiguous imagery of tactical finesse.[28] Combining illusions of tangible filaments and flaps, foldings and convolutions, platings and scraps with a fluid density of suspended shadowings, as if light and shade were quasi-substantial sponginess transmuted into hovering effluents, Duchamp moves from penetration and "revolution" ("revolving") in The King and Queen (May 1912) to "passage" as tumescent numbness in The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride (July-August 1912) to generation as “stillness” in the Bride (August 1912), a distillery of torture and alchemic instruments welded into a configural splendor of finely wrought contempt.

If one's rhetoric tends to become florescent (one is tempted to say fluorescent) in response to these works, it is because Duchamp, at this time, seems closest to the intensity of the flesh and its primal palpitations while metaphoring that "flesh" into structures of art. These art structures are hardly nonobjective, nor are they figurative in any easy sense. Rather they are constructs suffused with a quality of excitement that is distanced and displaced, absorbing pornographic potentials in the smoothness of paint cuisine (Duchamp kneaded the pigment with his fingers to "extra smoothness") and in the strangeness of their elaborateness. If there is little of orgasmic delight to grasp in these images, they are, we can hardly fail to suspect, Machiavellian in their sculptural aplomb and erotic in their depths. Their eroticism is a "black" eroticism rather like Sade's, but an eroticism that has been refined, distilled, and literally transfigured into a mechanism of distraction from the burden of rankling sex. If we foolishly seek to plumb the imagery's mysterious depths, making a human penetration into problems that Duchamp has consciously "walled off," we are checked by the resolute impenetrability of the quasi-sculptural intervening "sets," which have both presence and elusiveness as intellectual invitations and toughness and cunning as perceptual barriers to our heuristic thrusts.[29]

These images, in which Duchamp becomes Dada's "Poussin," are impersonal plumbings of a mind that "digests" the passions which are its materials and, in this case, its substrate. The sentience of the flesh as a kind of instinct substance needs the operation of the mind (what Duchamp called "gray matter") to trick the body into however grudging a respect for its rights and privileges of superiority.[30] By converting the body into an "almost" mechanized substance, the mind makes it into a web of anamorphic forms acting as a counterforce to the "contained" activities within and behind the works, activities hinted at, glimpsed, suspected, and suspect, which could, one feels, erupt at any moment out of the formal control of the image if it were not for the astringent finesse of the artist who has locked them into place.[31]

It is at this point that we really begin to understand the ruthlessness of Duchamp's need to control emotion through the metaphor of form. He does not want so much to "think things through" as to think against "thinking them through": hence the impenetrability of his articulations and the toughness of his art. By this decision to create paintings whose contents will not move beyond his controlling censorship. Duchamp can now, it seems, make "subjective" pictures that will not let their subjects "out." In this, the tactic of mechanization of his subjects and of his subjectivity is crucial in the overall strategy of what Duchamp and his paintings are all about, namely the containment of giros and the transmutation of pathos into a welcome absence of feeling, which for him was a victory of intelligence over the Caliban in himself. As repressors of instinct, Duchamp's images are a kind of infernal machine, but they regulate their own "meta-forces" in so cunning a way that we are tempted to call them mechanisms of affirmation as much as monsters at play.[32] They appear to be autonomous worlds of irrational thought, but their autonomy, however much it seems a function of pervasive forces within the works, is finally threatening only if one becomes involved in it personally. Only by assuming that it is one's business to enter into subjective traffic with the imagery, rather than merely to observe how it works, will our indifference be threatened by Duchamp's mechanomorphs.

It may not be easy to be so indifferent to images and objects as provocative as those of Duchamp. Peinture de precision, beaute d'indifference was a Duchampian goal he himself had to struggle to attain. While a meta-irony of indifference is the appropriate affirmation Duchamp tells us to adopt, his own efforts to fully master such a "set" led him, after the mechanomorphs, to an even more ruthless suppression of what, in contrast to what followed, seemed his previous "expressiveness." Only with his embarkation on the great project of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23), an enormous glass panel of autistic intercourse,[33] ancillary works such as Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals (1913), Chocolate Grinder, No. I and No. 2 (1913 and 1914), and various Readymades, such as bottle-drying racks, combs, bicycle wheels on stools, and other bric-a-brac, did Duchamp make a final commitment to full suppression of all "human" affect in his work.

Whether it be the tortured and tortuous "bride and bachelors," the ball of twine that is the "guts" of a Readymade called Hidden Noise, or the geometry book, called Unhappy Readymade, hung out to disintegrate into its "natural roots," each "subject" is clamped into a mechanical format or "nonsensized" beyond possible return to any original identity it may once have had. Each becomes a part of what may be called Duchamp's "field of nonsense," and a counter in a game that is both cruel and amusant.[34] Duchamp plays his game with a potential spectator (friend or enemy), of course, and it is this game that has attracted most attention from students of Duchamp's art. It is so complex and "open-ended" a game, involving extrapolations and decipherings, open interpretations and closed forms, reductions and expansions, inversions and reversals, additions and subtractions, divisions and multiplications, shocks and buffetings, foolishness and sense, that it can be only partially anatomized here. Each image after 1912, beginning with the wholly mechanistic drawing The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors of July-August 1912, which targets a central "bride machine" between two allogamous "bachelors," encodes some cunning rendezvous with an alerted idea which has not yet become knowledge and, therefore, carries with it the potential of further thought ascending through larger and larger dimensions of precipitous flight, with the viewer forced to follow in hot pursuit, as if the geometric ratio of Duchamp's cervellites was always one step beyond the horizon of the viewer no matter how "fast he runs.”[35]

If the works are n - 1 dimensional projects of an n dimensional realm, their output over input ratio of fantastic motivational ramification is n(n - 1). It is not just because these works are mechanistic that this output is achieved, though the mechanization of the work is a crucial step in allowing such an output, as we shall see. Rather it is because Duchamp now uses nothing but machines and machine forms, which are "like thematic apperception tests which discourage self-projection,"[36] in a strictly scaled game of nonsense arrayed against the vastness of a dreamlike transparency, creating a labyrinth of perceptual and conceptual gamesmanship in the mind of the viewer which ascends, by its own fictions of gratuitous effort, toward self-reflexive ecstasy. If the game of fictionalizing what, at its lowest level, is Duchamp's creative residue becomes a form of infinite Dada delight in "going too far" and succeeding in that excess of delirious play, this overreaching of logical interpretive extension is an intellectual game we are able to play because Duchamp has presented us with an infinitely ambiguous set of relationships open to the wildest Brissetian or Rousselian orders of incongruous fantasy. Learning something, no doubt, from those linguistic madmen, but essentially inventing his own forms of countersense out of his own psychic need, Duchamp releases both himself and us, his audience, from the burden of logical necessity, enabling us to play freely and madly, with whatever fervor we please, a game of "delirium metaphor" to a historically unprecedented degree.[37]

The words "nonsense" and "field of nonsense" used above are employed by Elizabeth Sewell in a more specific sense that provides an unexpected insight into Duchamp's syntactical methods after 1912. For Sewell and for Duchamp, nonsense is a game played with fixed counters against the boundlessness of "dream"-dream taken both in its literal sense and as the intuition of infinite analogy possible in a world "beyond the looking glass," as in Alice's adventures, where the farthest reaches of fantasy escape the bounds of language, reason, restraint, or "reality" of any kind other than that which is "dreamlike" and, hence, imaginative infinity.[38] Nonsense in Duchamp's case involves juxtaposition and superimposition of mechanisms and machine forms of a specific configuration (after 1912) and discrete separateness of placement[39] (however much "tied together" by mechanical connections or rigid links). The nonsense game involves, as other highly developed games do, "the active manipulation... of a certain object or class of objects, concrete or mental, within a limited field of space and time and according to fixed rules of play, with the aim of producing a given result despite the opposition of chance or opponents."[40]

This definition of a game is "Dadaized" by Duchamp, who takes the limited space to be the translucency of a glass panel or the emptiness of a room where we find a Readymade, while the limited time may be a minute, an hour, or a whole life. The objects and counters in the Duchamp game are, of course, the paraphernalia of machines and mechanisms, but they are also forms and systems, illusions and mirrorings (literal or figurative), titles and imports-all of which are the counter personae and presences of Duchamp's "works." The field of play is not only the "perspective" of the images (and the perspectives we bring to them), but the ambience of the works in relation to the perceptual and conceptual rapports of the viewers of these works. According to the "fixed" rules, which always seem to be asking to be changed as we play the game, we begin by taking seriously what we see, trying to make sense of the relationships we are faced with-and then abandon that seriousness in favor of Dada hilarity. The operation of chance is, on the whole, the opposition we face: chance as distraction and lack of sense. But our opponent is also the imagery itself (we must "take" the chance), which must be mastered by going beyond the plausible. In this respect Duchamp's nonsense is a set of strict relationships and a matter of flexibility, a paradox to reason but a new and very twentieth- century poetic of converting the given and the banal into apparitional potency.[41]

The scale of conversion from the givens of grinders and dummies, of cylinders and scissors, of hatracks and typewriter covers to the freedom of unimpeded hyperbolic thought is so great that only a kind of "short circuit" of intelligibility can lead us from the pathos to the ethos of the Large Glass and the Readymades, happy or unhappy, which are its offspring or counterparts. This short circuit of our normal ways of using visual imagery is grounded in a logic of mental relations subject to its own laws, limited and controlled by reason and will, set within and against a suppressed power of cogent irrationality. Dedicated basically to "balance and safety," this logic of mental relations, which is "nonsense" instead of "sanity," postpones the effect of climax which is orgasmic irrationality.[42]

With the strictness of machinery applied to the fantasy of seduction and masturbation, Duchamp breaks the indices of that fantasy into small units set side by side. Counting on the deflection of intention by a concrete and fastidious arrangement of schematic objects as "non convertible currency" in a game of sexual exchange, Duchamp uses his translations of affect into intellect as a nonsense order to limit multiplicity, to sterilize action, and to convert impulse into "an order" of a "nonconvertible" kind.[43] For nonsense is a nonconvertible currency unless it is converted into dream. Being "nothing but itself," nonsense, with its careful selectivity of juxtaposed un-intelligibilities, is a multiverse that is never more than the sum of its parts. Dream, on the other hand, is a universe that is always more than the sum of its parts because its contents are organically (and not mechanically) comprehended by its infinite interrelatedness. Combining nonsense and calculation with poetic invitations to Surrealist ecstasy (as he combines linear perspective with visual indeterminacy), Duchamp plays a short-circuit game with himself and the "beauty of indifference," which becomes an equation of existential pathos and creative purity.

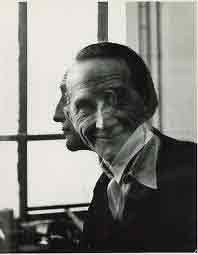

Marcel Duchamp, 1953.

If we as viewers can use his art as a vehicle for self-transcendence into a kind of dream work that is a "moral holiday" (to use William James's suggestive term), we see how, for Duchamp himself, the achievement of "seeming to be one's own cousin and yet still being oneself" was the product of working out a curious mixture of exhaustion and emptiness and an almost machinelike indifference to existential consequence. The elaborate mechanism of the Large Glass, the "stupidity" of the simpler Readymades, the geometrics of Tu m', the unachieved projects of the Notes-these and the whole strategy of calculated outrages against the expectations of "normalcy" were essential steps in Duchamp's freeing himself from contingency by a calculated contempt for "future shock" and "present shortcomings" articulated through Dada, which became a form of art. For Duchamp's work, strange as it is, is art, albeit of a very special kind ; an art of living as well as an art of mechanisms and a nonsense of machines.[44] By mechanizing the contingent into a field of nonsense, Duchamp devalues its depreciative power on his essential self-esteem; by the conversion of psychic pressure into tautology, he transfigured it into absurdity, an absurdity he could deride. By thus projecting exigency into nonsense he could provide a model, in concrete instances, of how to achieve a sophisticated neutrality of interested indifference to all existential events. In this way Duchamp could be both master of his destiny and never out of touch with what "really mattered" to him, as long as what mattered was filtered through his nonsense and his pride.

Wishing to become essentially a relationless entity centered on himself, Duchamp found the machine, a willing instrument of his passion, to be truly passionless. As an intangible presence in every one of his works, Duchamp could resemble the godlike artificer of Flaubert and Joyce paring his finger fingernails while his mechanisms "did their work." The échec (block or check) in the imagery, which we have called nonsense, is the contradictory banished to the realm of language and its infinite artifice. What is caught in this trap is both contingency (the limiting action of the world and time) and the aspect of Duchamp himself that is an excess of complexity which he really wants to "check." By catching and exhibiting this complexity (one is tempted to say not "complexity" but "complex"), Duchamp can stand above and beyond himself without quite losing touch with what exercises his fantasy and "touches his heart." Like the phrase "definitions, by definition, define," which, when repeated once, then twice, then three times, becomes a redundancy that at first seems clear and then opaque and finally a numbingly translucent nonsense of eulalic, ritual delight, Duchamp through his art converts himself and us into labyrinths of pure mentality contemplating our own contents. If that nonsense is more than a matter of playing with anxious artifice, the result may be poetic fulfillment somewhere between Mallarme and Lautréamont. Its formula of conversion is

1/0 = infinity∞; it is as simple and as nonsensical and as complex as that!

Feed into this formula equal amounts of involvement and indifference on our own and Duchamp's part, and one will understand, as far as it can be understood by ordinary people, the meaning of his art. As a component of that meaning, the machine was always a means and never an end, but it was a target for Duchamp's hostility and an instrument of his release from the servitude of having to be himself without the advantage of transcending his involvements with matters beyond himself. If the image of Duchamp as a "relationless entity" centered on himself is a fiction we are hypnotized into believing in spite of rational doubts, that only goes to prove that art is illusion, even in the hands of Duchamp. Such illusions, however, are psychological facts, and even if we can arbitrarily resolve the whole thing into nothing, that resolving into nothing is "where Duchamp is at"-for the nothing that is his cipher is a divisor and not a quotient. Between unity and nothingness is the infinity of Duchamp. As he said in a note on conditions of a language, "the search for prime words divisible only by themselves and by unity" was a basic enterprise to which he dedicated his life. If a prime word is, in essence, self-reflexive, it is also autonomous, even if the mechanism of its autonomy is pure fiction, a contentless nothingness.

Mallarmean as he was, Duchamp was willing to become a fiction of his own idea of himself.[45] In this self-transformation, the machine was both a motor force and a catalyst, crucial for his personal and untraditional alchemy of achieving "fool's gold" out of what would have been others' "dross." What was dross was his Kierkegaardian humanity, but, to him, that was what he needed to abolish! Like his Anemic Cinema, in which self-transforming spirals and punning disks rotate elliptically without ultimate gain or loss, Duchamp became the "negation of his own negation," a kind of dialectical neont, which told him, with "the blankness of dada," that he was not as "blank" as he had thought. If Duchamp was hardly an angel (unless we think of Lucifer as one), he was also not a machine; that is why he converted the mechanism of nonsense into the alphabet of dreams. What others could make out about this alphabet was a matter of general unconcern to Duchamp, though on the "art level" he admitted that the spectator qualified and "completed" the work. What he made out of it, his oeuvre, is more than a matter of machines, although some interest in the machine is a prerequisite for dealing with Duchamp on any level and to any significant degree.

What is more important is that the viewer, whoever he may be, have an extraordinary capacity to understand and enjoy nonsense, in itself and extensively, as a mode of redefining an appropriate measure of order between pathos and ecstasy. If he can do that, he will be at the heart of the matter, which is located about 180 degrees from where most people see nonsense as standing-that is, not on the other side of reason, but on this side of dreams. Accept that and the machine will begin to detach itself-without wholly losing touch with Duchamp's own capacity for pathos and ecstasy–from the humanity of the artist, which is of less importance to us now than the efficacy of his manner of transcending his own limitations through an art that made him free.

* Steefel, Lawrence D., Jr.; Marcel Duchamp and the Machine. In Marcel Duchamp (eds. Anne D'Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine), New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1973, pp. 69-80.

Notes:

[1] See Marcel Duchamp, "The Creative Act," in Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp (New York: Grove Press, 1959), p. 77.

[2] Elizabeth Sewell, The Field of Nonsense (London: Chatto & Windus, 1952). See also Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Arts in France, 1885-1918 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1958), p. 258. For Duchamp's mood and a characterization of him as a "sad young man," see Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, "Some Memories of Pre- Dada: Duchamp and Picabia," in The Dada Painters and Poets, ed. Robert Motherwell (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1951), pp. 255-58. "Hygienic" was a favorite word of Duchamp, and Laforgue's Hamlet was an early locus classicus for his baffling discontents

[3] For "mediumistic being," see note 1. For "blankness of dada," which taught Duchamp that he was not as blank as he had thought, see "Eleven Europeans in America," ed. James Johnson Sweeney. Museum of Modern Art Bulletin (New York), vol. XIII, nos. 4-5, 1946, pp. 19-21.

[4] The notion of "short-circuit" is derived from Duchamp's notes for the Large Glass and the "blossoming of the bride."

[5] "Irony is a playful way of accepting something. Mine is an irony of indifference. It is a 'meta-irony.'" See Harriet and Sidney Janis, "Marcel Duchamp: Anti-Artist," in Motherwell, Dada Pointers and Poets, pp. 306-15.

[6] "Debrained" is a Jarryesque term, a favorite of Duchamp, and cervellites is a Duchampian neologism for thought products- or "brain facts."

[7] A useful pragmatic aid in achieving this climactic effect, which is a consequence of great perceptual effort in looking at the Coffee Mill, is provided (without reference to Duchamp) by Anton Ehrenzweig, "The Pictorial Space of Bridget Riley," Art International (Lugano), vol. IX, February 1965, pp. 20-24. By imagining Riley's Blaze 1, 1962 (p. 20), surmounting Twist, 1963 (p. 24), as "accelerations" of Duchamp's Coffee Mill, one can more easily achieve the transformation of the Coffee Mill from pattern to "presence" just noted.

[8] For possible semantic extensions of this perceptual process, see Steefel, The Position of "La Mariée mise a nu par ses celibataires, méme" (1915-1923) in the Stylistic and Iconographic Development of the Art of Marcel Duchamp, Mic. 61-2004 (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1960), pp. 113-27; for the mill as mandala, see Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, p. 74; and for the key role of the mill in Duchamp's artistic development, see Janis, "Duchamp: Anti-Artist," pp. 309-11.

[9] Interview, 1956. For a related comment on "science," see Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking, 1971). p. 39.

[10] See Duchamp's comment on Mallarme in James Johnson Sweeney, "Eleven Europeans in America," p. 21. See also Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, pp. 30, 40,105. For the most "Duchampian" of Mallarme's creations, conceived as early as 1866, worked on mostly after 1894, and left inachevé at his death, see Jacques Scherer's Le "Livre" de Mallarme (Paris: Gallimard, 1957), pp. 155-380, which presents the text of a set of notes for a theàtre imaginaire in which time is suppressed and mastered.

[11] Interview with Steefel, 1956. See also Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 72.

[12] There has been much debate as to whether the "nude" moves. Duchamp said he did not want "cinematic effects" but admitted that everyone, including himself, saw motion in the image. Interview with Steefel, 1956. See also Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 30.

[13] For further analysis of this image, see Steefel, Position of "La Mariée," pp. 107-113.

[14] For Marcy, see Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography (Baltimore: Penguin, 1969), pp. 199-210, and Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (New York: Oxford University Press, 1948), pp. 17-28.

[15] For "body image," see the penetrating discussion of body perception in Paul Schilder, The Image and Appearance of the Human Body (New York: International Universities Press, 1950). For the body as instrument, subject, and presence, see Matthew Lipman, What Happens in Art (New York: Appleton, Century, Crafts, 1967), pp. 67-80.

[16] See Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, p. 9.

[17] This "coldness" is perfected as "the beauty of indifference" in what may be the finest version of the image, the Philadelphia Museum's "Blue Nude," produced on the format of the 1912 painting, photographed and "assisted" by Duchamp in 1916.

[18] For "turning inward," see Duchamp in Sweeney, "Eleven Europeans in America," p. 20. For the context of desperation and hope, see Janis, "Duchamp: Anti-Artist," pp. 311-12.

[19] If Duchamp had simply transposed a Marcy schematic image as a procedure for his Nude, there would have been no "unabsorbed difficulty" for the viewer to face. It is hard to believe that such a borrowing would have been too radical a step for Duchamp to make. Rather, one feels it would have been too easy for him-which, if true, points to his concern with ego in making his own Nude in a more personal way than he would have chosen to do after 1912, and also to the process of " disincarnation" and "decomposing" his work was undergoing at this time.

[20] Interview with Steefel, 1956. For the creative process, see note 1, above. For "chance" and Duchamp, see Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, pp. 95-97. For "the mind" and "aleatory order," see Frank Kermode. "Modernisms Again." Encounter (London), no. 26 (April 1966), pp. 65-74.

[21] See Janis, "Duchamp: Anti-Artist," pp. 311-12; Arturo Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, passim; and Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, pp. 74-75.

[22] "Before he had, so to speak, purged himself of it, Duchamp had let us feel, through the sarcastic atmosphere in which he enveloped it, that the universe of his works was for him the anti-world.... It is the intolerable world of reality which he 'brushes aside' as one would wave away a nightmare, by fixing it in the Glass [and other works]." Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, p. 72.

[23] For the rejection of aesthetic finesse, see Sweeney, "Eleven Europeans in America." pp. 20-21.

[24] Max Kozloff, "Duchamp," The Nation (New York), vol. 200, February 1, 1965, pp. 123-24.

[25] For these images, see Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, pp. 10-15 ; Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Abrams, 1969), pp. 103-20: and Steefel, Position of "La Maride," pp. 133-50.

[26] See Michel Foucault, "7 Propos sur le 7’ ange," in Jean-Pierre Brisset, La Grammaire logique (Paris: Tchou, 1970), pp. vii-xix, and Brisset's own text.

[27] The most compelling frame of reference for I'etat brut of Duchamp's obsessional matrix is Georges Bataille's Death and Sensuality: A Study of Eroticism and the Taboo (New York: Ballantine, 1969), pp. 5-19 and passim.

[28] For a detailed analysis of one image in this suite, The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride, see L. D. Steefel, Jr., "The Art of Marcel Duchamp," Art Journal (New York), vol. XVII, no. 2 (Winter 1962-63), pp. 72-80.

[29] "Problems are nonsensical. They are human inventions." Duchamp, interview with Steefel, 1956.

[30] Duchamp may have been aware of the Greek root of "machine": mechane, trick or ruse.

[31] For a detailed study of this complex point, see Steefel, "The Art of Marcel Duchamp," pp. 73-74.

[32] "A human body that functions as if it were a machine and a machine which duplicates human functions are equally fascinating and frightening. Perhaps they are so uncanny because they remind us that the human body can operate without a human spirit, that body can exist without soul." Bruno Bettelheim, "Joey: A 'Mechanical Boy,'" Scientific American (New York). vol. 200, no. 3 (March 1959), p. 117.

[33] For a responsible discussion of the ambiguous issue of Duchamp's "autisms." see Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, pp. 70-75.

[34] See Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 40.

[35] For the geometric ratio of Duchamp's "speculative intrigue" as played into the evolution of the Large Glass, see Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, pp. 39-40. For more on Duchamp and the "fourth dimension," see L. D. Henderson, "A New Facet of Cubism: The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry Reinterpreted," Art Quarterly (New York), vol. 34, no. 4 (Winter 1971), pp. 410-33. For a fascinating parallel to the oneiric articulation of Duchamp's dimensionality, see Lewis Carroll, "Through the Looking Class," The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll, Modern Library (New York: Random House. n.d.), pp. 162-67.

[36] Kozloff. "Duchamp," p. 124.

[37] See Andre Breton, "Lighthouse of the Bride," in Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, pp. 88-94. Cf. Duchamp's interview with Steefel, 1956: "You can do anything you want with these," said Duchamp, referring to the works.

[38] Sewell, The Field of Nonsense, pp. 1-6. 25-26. 41-43, and especially 44.

[39] Ibid., pp. 44-54.

[40] Ibid., p. 27.

[41] Ibid., pp. 55-80, 115-29.

[42] Duchamp spoke, in the early stages of his thought about the Large Glass, of un retard en verre, or "a glass delay." The postponement of climax may he the meaning of that phrase which has remained otherwise unexplained.

[43] For distinctions between "in order," "an order," and "order," see Kermode, "Modernisms Again."

[44] "If today the elaboration and execution of the Glass can simultaneously suggest asceticism and the Great Work of the alchemists, or some apparently trifling exercises in Zen Buddhism, Duchamp's experience remains nonetheless unique, empirical and inconclusive as it is. Confronted with the crises of modern times which he had first to live through. and in the face of all formulae, all illusions, all doctrines, he has raised his enigmatic monument to the free disposition of one's self, and in addition he has restored a reason for existence to the work of art he meant to abolish." Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, p. 75.

[45] "To strive to make oneself the most irreplaceable of individuals is, for all practical purposes, to strive never to resemble one's fellow men, and for some, at least, not even to resemble oneself. This is a singularly attractive undertaking. A kind of underground spirit drives man to experiment with the extremist possibilities of self-metamorphosis. The question is whether it is possible to enrich one's nature and achieve a new awareness of one's total being by overruling the resistance of reason and habit, by forcing one's imagination to leap into the unknown, beyond any beaten track. This implies a readiness to destroy the traditional concept of man, and, first of all, to destroy one's personal being, to let it be absorbed and lost in a selva oscura.... More than that: this very activity. this mental proteanism, this way of living and constantly renewing one's life is poetry." Marcel Raymond. From Baudeluire to Surrealism (New York: Wittenborn. Schultz. 1950), pp. 220-21.