Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp - Andy Warhol

sitemap

drawings

paintings 1 2 3 4 5 5 a b c -

- A B . . . . . . . new

installations

projects

reviews

Hans Herion (1852-1911) |

Hans Herion (1852-1911) |

Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp - Andy Warhol

Victor P. Corona

Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp / Andy Warhol*

Had he survived a routine surgical procedure, Andy Warhol would have turned eighty-two years old on August 6, 2010. To commemorate his birthday, the playwright Robert Heide and the artists Neke Carson and Hoop organized a party at the Gershwin Hotel in Manhattan’s Flatiron District. Guests in attendance included Superstars Taylor Mead and Ivy Nicholson and other Warhol associates. The event was also intended to celebrate the Andy Warhol: The Last Decade exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum and the re-release of The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol (Wilcock, 2010). Speaking with some of the Pop artist’s collaborators at the ‘Summer of Andy’ party served as an excellent prelude to my visit to an exhibition that traced Warhol’s aesthetic links to one of his greatest sources of inspiration, Marcel Duchamp. The resonances evident at the Warhol Museum’s fantastic ‘Twisted Pair’ show are not trivial: Warhol himself owned over thirty works by Duchamp. Among his collection is a copy of the Fountain urinal, which Warhol acquired by trading away three of his portraits (Wrbican, 2010: 3). The party at the Gershwin and the ‘Twisted Pair’ show also provided a fresh opportunity to explore the ongoing fascination with Warhol’s art as well as contemporary works that deal with the central themes that preoccupied him for much of his career.

Since the relationship between the Dada movement and Pop artists has been intensely debated by others (e.g., Kelly, 1964; Madoff, 1997), this essay will instead focus on how Warhol’s art continues to nurture experimentation in the work of artists active today. My interest in the long shadow that Warhol casts over cultural production is certainly not new. Almost a decade after his death, Kakutani’s ‘United States of Andy’ essay described him as a ubiquitous presence, a bespectacled, silver wigged ghost hovering over the culturescape like a faintly bemused angel (1996). Although a survey of the international art world is beyond the reach of this essay, I will use ‘Twisted Pair’ as a means of tracing how the Warholian inheritance still informs and provokes new works of art, performance pieces, pop music, and academic inquiry. Although Kakutani was right to interpret the work of Cindy Sherman and Damien Hirst as post-Warholian art, the artists I refer to throughout this essay stand firmly on their own, expanding and complicating the terrain of the present day’s culturescape.

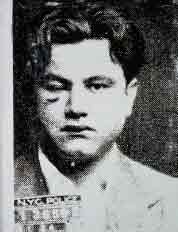

Andy Warhol; Most Wanted Men No. 2, John Victor G. 1964.

As the exhibition explains, ‘twisted pair’ actually refers to an electrical innovation in which two wires are intertwined in order to avoid electromagnetic disturbance. Bringing together works by two of the twentieth century’s most influential artists shows the vibrant energy and affinity between their unusual and often shocking creative visions. As the show’s curator notes, the two artists were linked by an interest in optical-effect experiments, language and puns, pseudonyms, sexuality, identity and role-playing, money, fame and death (Wrbican, 2010: 2). The clearest example of this affinity is probably both artists treatment of the Mona Lisa. In Warhol’s prints, more shadows appear on her face in one silkscreen than another, which yields a more aged and somber version right next to a luminescent, almost auratic face. Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., one of his most famous works, is of course a mocking interpretation of what remains a sacrosanct work of Western art. More broadly, the Warhol Museum’s side-by-side display of both artists work demonstrates their shared interest in a kind of recombinatory experimentation with different media as well as an attempt to convey some sense of the desires and anxieties that characterized their historical moments.

Marcel Duchamp; L.H.O.O.Q. 1919.

As a sociologist, the most interesting point of comparison for me was the fascination both artists seemed to have with the malleability of identity. When he began his career, Warhol modified his own surname by dropping the last letter of Warhola. A framed silver and black wig in ‘Twisted Pair’ reminds the viewer that the most recognizable aspect of the Pop icon was a fake. Duchamp’s ‘readymades’ provoked a scandal about the integrity and identity of the artist and his oeuvre. His Five-Way Portrait, created in 1917, plays on the multiplex nature of individual identity and the many faces a single person can display. This curiosity about the fungible character of the individual was fittingly captured by photographs of the two artists in drag, what Warhol referred to as a social-sexual phenomenon (Warhol & Hackett, 1980: 281). But whereas Duchamp dressed as ‘Rrose Sélavy’ is a hazy, almost comical vision of the affectations of a 1920s doyenne, Warhol dressed in several drag outfits is a startling series of pale faces, sunken cheeks, and bright lipstick. These photographs become grotesque parodies of desperate efforts to conserve youth, images of failed glamour that are quite distinct from the Factory’s drag performers, particularly Candy Darling and Mario Montez. For some Superstars, drag performers and otherwise, adopting new names, personas, and appearances was not enough. Together with Warhol, they initiated antistar identity games intended to confuse the press and the inquisitive. These inside jokes would entail the Factory coterie lying about which Superstar was which, what Warhol called playing switch-the-superstar (Warhol & Hackett, 1980: 312).

In addition to drag performers, Warhol also engaged another kind of New York underground. His silkscreen portraits of thirteen criminals were originally intended for a mural at the New York State Pavilion of the 1964 World’s Fair, a visual statement which unsurprisingly irked the show’s administrators. Portraiture typically seeks to preserve and enhance the likeness of an individual who wishes to be remembered by posterity. The mugshots used by Warhol, in this case the thirteen criminals most wanted by the New York Police Department, amount to a social documentation of men who had attracted infamy and punishment for their offenses. Portraitists usually offer a transfiguration of their subjects; Warhol’s silkscreens capture the consequence of their transgressions. Warhol’s portraits of the fallen demonstrated that these criminals were as much a part of urban popular culture as the cinema idols, socialites, and downtown misfits he so carefully documented. These silkscreens had a prescient quality to them in the sense that one still awakens to find mugshots plastered across newspapers front pages, usually featuring the latest disheveled celebrity arrested for drug use, drunk driving, or worse.

Conrad Ventur; Bibbe Hansen and Billy Name (Screen Tests). 2010.

Aside from his artworks and the Foundation for the Visual Arts funded by his estate, Warhol’s legacy also consists of the actual materials and mementos he gathered in six hundred boxes. Now known as his time capsules, this collection of artifacts is extremely valuable to researchers and art historians and is part of an ongoing cataloguing effort. Time capsules reflect his desire to document and understand the tumult of the time in which he was living, particularly the rise of Pop as an idea that had finally penetrated the American experience, a theme that recurs in his memoirs. The items on display in ‘Twisted Pair’ include Warhol’s personal correspondence, a Fantastic Four comic book, the announcement of a Roy Lichtenstein show at the Irving Blum Gallery, and the lease for the Silver Factory.

A work exhibited at another Pittsburgh museum is a kind of room-size time capsule filled with pop artifacts and populated with garish, limbless dolls. Installed at the Mattress Factory, It’s all about ME, Not You was created by Greer Lankton, a transsexual who died of a drug overdose in 1996 shortly after completing the installation. Heart-shaped lights frame a ceiling covered in stars. Astroturf lines the floor, where Lankton’s handmade dolls are spread out in tortured poses, each distorting the female figure. The focal point of the rather disturbing room is an armless female mannequin lying in a bed covered with pill bottles, apparently incapacitated by her addictions. One wall panel is covered with Christian prayer cards and crucifixes, while another panel is devoted to Superstar Candy Darling, who died of leukemia without having achieved her dream of Hollywood stardom. Since the room is enclosed, one looks into the space like a voyeur assessing the remnants of a life of anguish and trinkets, a world where Raggedy Ann, drugs, Jesus Christ, and Superstars are all sought as sources of comfort.

Conrad Ventur; Screen Tests Revisited. 2010.

Warhol’s own role as pop portraitist and ‘voyeur-in-chief’ (Hughes, 1982) is closely associated with the screen tests he would film of people he considered beautiful or interesting. This past spring, New York artist Conrad Ventur revisited Warhol’s Screen Tests by asking some of the original Superstars who ‘performed’ in the 1960s versions to again sit before a camera. The stars of these new screen tests included Bibbe Hansen, Mario Montez, Billy Name, Ivy Nicholson, and Ultra Violet. What Ventur has elegantly done is recreate the meditative experience of scrutinizing a person’s visage, each line in their face, every blink, each stirring of a smile or grimace. The product of Ventur’s exploration of elapsed time is an almost solemn consideration of the faces that played key roles in the Factory’s social laboratory, a scene that has since become an incredibly mythologized space. As Ventur told Dazed & Confused, The forever-ness of the myth-bit created in the mid-60s gets a kind of blip in 2010 (Pryor, 2010). Like the originals, the contemplative moments provided by Ventur reveal much about the intimacy produced by staring at a person’s face, what Henry Geldzhaler described as an entire history of gestures after viewing his own screen test (Wilcock, 2010: 65). Alongside films like Sleep (1963) and the eight-hour long Empire (1964), these tests illustrate the extent to which Warhol’s movies were an amplification of his portraiture. Warhol himself characterized his feature films by claiming, I only wanted to find great people and let them be themselves and talk about what they usually talked about and I’d film them for a certain length of time and that would be the movie (Warhol & Hackett, 1980: 139).

Lady Gaga; Who Shot Candy Warhol: The Heart. 2009.

Ventur’s restagings of the Screen Tests and his additional experimentation with past performances by the singers Nina Simone and Shirley Bassey sustain ongoing discussions about the nature of reperformance. Marina Abramović is most responsible for triggering this debate through her reperformances at the Guggenheim in 2005 and her extremely successful retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2010. In addition to other artists reperforming her pieces after extensively training with her, Abramović performed in the MoMA atrium for a three-month period during which visitors could sit across from her for as long as Ventur’s restagings of the Screen Tests and his additional experimentation with past performances by the singers Nina Simone and Shirley Bassey sustain ongoing discussions about the nature of reperformance. Marina Abramoviæ is most responsible for triggering this debate through her reperformances at the Guggenheim in 2005 and her extremely successful retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2010. In addition to other artists reperforming her pieces after extensively training with her, Abramović performed in the MoMA atrium for a three-month period during which visitors could sit across from her for as long as they desired. Part of what was so compelling about this performance was that her gaze made complete the one-way spectacle of Warhol’s screen tests. Through this performance, the subject of the portrait stared back, at times reducing the sitters to tears. Several cameras captured the expressions of both Abramović and the sitters, with one video camera transmitting a live Internet feed. Offering herself as a kind of portrait’s subject in vivo, Abramović’s performance consisted of a double screen test that persisted for three months. Both the Abramović retrospective and the Ventur screen tests extend the ambition and curiosity evident in Warhol’s portraiture and films while also demonstrating the distance possible between the artist and her or his work. Phelan (2004) noted this resonance between Abramović and Warhol, arguing that while they took different routes to arrive at the notion that they were not necessary to completing their work, and while they had different reasons for believing in the impersonality of art, their mutual conviction that the artist’s consciousness is not necessary for art is worth pondering (572).

Lady Gaga; Who Shot Candy Warhol: The Brain. 2009.

Duchamp, of course, clearly understood the distance possible between art and artist. Alongside Robert Rauschenberg and others, the Dada icon’s work also nurtured in Warhol tastes for aesthetic bricolage, use of different media, and an interest in great cultural symbols. Three years before Warhol died, his silkscreen of Michael Jackson was used for a Time cover article on the soon-to-be King of Pop and ‘why he’s a thriller.’ Today, it is not difficult to see the multimedia bricoleuse in one of Warhol’s greatest inheritors: the pop star of the moment, Lady Gaga. Other scholars have also effectively characterized this link: [Gaga] surpasses Warhol through her discovery of the medium of Pop. For where Warhol transformed art into Pop and thereby created a new representational genre, Lady Gaga has transformed Pop into an art with a set of aesthetic convictions, possibilities, and ambitions all its own (Panagia, 2010). This argument points to the ability of the young music star’s self-proclaimed mission to use her albums, videos, performances, and use of avant-garde fashion to demonstrate once and for all that pop culture ‘will never be low brow.’

Perhaps the most explicit example of Gaga’s Warholian inheritance consists of three short film pieces shown as introductions or interludes during her past concerts. The three-part Who Shot Candy Warhol series begins with her describing how Pop ‘ate her heart,’ thereby setting her free. An excellent exegesis by Moralde (2009) describes them as homages to Warhol [that] include relying on minimalist settings to the point of abstraction and investing a great deal of attention on repetitive actions such as taking off gloves or brushing hair (which itself is quoting a scene from Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls).’ Endless hair brushing also occurs in Warhol’s Batman Dracula (1964) and constitutes the entirety of a 1975 performance piece by Abramović called Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful.

In a recent Vanity Fair feature (Robinson, 2010), the British photographer Nick Knight captured Gaga wearing a metallic corset and massive dress made of a transparent, plastic-like material designed by Armani Privé. The image was aptly titled ‘The Exploding Plastic Inevitable,’ recalling the multimedia shows produced by Warhol, the Velvet Underground, Nico, and Factory assistant and poet Gerard Malanga. The Vanity Fair photo shoot was but one instance of Gaga’s collaborations with Knight and his SHOWstudio, which his website describes as a fashion and art internet broadcasting channel. Gaga has found common cause with Knight’s interest in various media and a desire for incessant creative experimentation. It was therefore not surprising when she stated, Nick Knight for me is our Andy Warhol. I think he is the great artist of our time. He embraces technology, fashion, photography, video, art, sculpture’ (Collins, 2010: 131). Gaga also collaborated with Knight on a Fountain-inspired work titled ‘Armitage Shanks,’ in which she inscribed a urinal with the words, ‘I’m not fucking Duchamp, but I love pissing with you.’

Inspired by Warhol’s Factory as a hub of creativity, Gaga assembled collaborators into a ‘Haus of Gaga’. The most prominent members are creative director Matthew Williams (whom Gaga has nicknamed ‘Dada’), stylist Nicola Formichetti (also fashion director for Vogue Hommes Japan), and choreographer Laurieann Gibson. According to Formichetti, their group is a ‘religion’ whose mantra is simply to ‘just be whoever you want to be’ (Reardon, 2010: 137), a sentiment in line with the core of the artistic ethos of Warhol’s work. As his fascinating POPism memoir stated, ‘The Pop idea, after all, was that anybody could do anything, so naturally we were all trying to do it all. Nobody wanted to stay in one category; we all wanted to branch out into every creative thing we could’ (Warhol & Hackett, 1980: 169). As Gaga’s fame grows, Haus members have used their own Twitter followings and Facebook pages to introduce fans to the work of artists, designers, musicians, and others who they might not have otherwise encountered, thereby continuing the kind of syncretic aesthetics that the Factory nurtured.

Other extensions and reimaginings of pop portraits can be detected in the Neo-Pop imagery and sculptures of Jeff Koons, the Superflat work of Takashi Murakami, and the apparel of designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, whose fashion incorporates Snoopy, teddy bears, Converse sneakers, and, perhaps most famously, the Muppets. The photographer David LaChapelle, who has produced vibrant, surrealist imagery of pop stars like Madonna and the late Michael Jackson, began his career at Warhol’s magazine. As his personal website states, he was offered a job at Interview because ‘his work caught the eye of his hero Andy Warhol and the editors.’ Warhol’s own work continues to figure prominently in the New York art world. Aside from the Brooklyn Museum’s ‘Last Decade’ show, the MoMA will launch an exhibition of Warhol’s silent films in December 2010. The Steven Kasher Gallery will show photographs and other works that capture the ambiance of Max’s Kansas City, the New York cultural hub that served as a gathering place for Warhol, David Bowie, Aerosmith, and others. Virtual and actual reviews of Warhol’s career also trace the impact of his art and the Factory coterie, from the encyclopedic Warholstars.org site maintained by London-based Gary Comenas to the Warhol Tour in Manhattan run by Thomas Kiedrowski, author of a forthcoming book on the various Manhattan locales where Warhol lived, worked, and socialized.

As anyone interested in Warhol’s Factory quickly realizes, the study of that scene and satellite spaces like Max’s Kansas City quickly becomes a kind of sociometric inquiry into who worked with whom when and where. I was reminded of this recently while seeing Warhol’s Oxidation series at the ‘Twisted Pair’ exhibition. Warhol was assisted in these works by his studio assistant and artist Ronnie Cutrone. His former wife Kelly Cutrone now leads the Manhattan-based public relations firm People’s Revolution and burst onto the pop culturescape through her appearances in MTV’s The Hills and The City and her own Kell on Earth reality show. As she gained fame for her fearsome candor with young people trying to build careers in the fashion and public relations industries, Cutrone explained that she herself “was raised in a circus-like atmosphere in New York by the Warhol family” (Gilewicz, 2007) and is friendly with filmmaker and Warhol associate, Paul Morrissey (Bryan, 2008).

At the Gershwin Hotel gathering of the ‘Warhol family’ in early August, several members of the next generation were in attendance. As wall-length images from Warhol’s Screen Tests were being projected, they mingled with Factory regulars, posed for photos, and networked. They are part of a much larger community of cultural producers that has thoroughly disregarded any demarcations between the worlds of art, fashion, music, performance, and technology, thereby building new modes of creative expression that can surpass even the imagination of the man born in Pittsburgh eight decades ago. During the party, Taylor Mead sat on a couch chatting with Golden Globe winner Sally Kirkland, herself the subject of a 1964 screen test. Dressed in silver, the actress Penelope Palmer danced a few steps away (her own screen test was done while she was still an infant). On the wall behind the stage, Edie Segwick’s face stared out at the guests, who gradually slipped into a mood of festive remembrance and slightly somber inebriation. I thought back to this moment while I roamed the rooms of ‘Twisted Pair’ a few weeks later. At one point, I turned a corner to see a large projection of Duchamp’s 1966 screen test, filmed by Warhol just two years before the Dada artist’s death. During the four-minute video portrait, Duchamp grimaces, puffs on a cigar, drinks from a glass, looks off camera, and mischievously smiles, perhaps acknowledging the new spaces of scandal and experimentation that he and Warhol nourished.

(The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburg, 23 May-12 September 2010)

* Culture Machine Reviews, September 2010, pp. 1-12. www.culturemachine.net

References:

Bryan, M. (2008): Dark Angel of The Hills, New York Observer (June 17).

Collins, H. (2010): The World Gone Gaga, i-D (Pre-Fall).

Gilewicz, S. (2007): The Insider: Kelly Cutrone, Nylon (August 24).

Hughes, R. (1982): The Rise of Andy Warhol, New York Review of Books (February 18).

Kakutani, M. (1996): The United States of Andy, New York Times (November 17).

Kelly, E. T. (1964): Neo-Dada: A Critique of Pop Art, Art Journal 23: 192-201.

Madoff, S. H. (1997): Pop Art: A Critical History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Moralde, O. (2009); Pop Ate My Heart: Lady Gaga, Her Videos, and Her Fame Monster, Slant Magazine (December 14). Available: http://www.slantmagazine.com/house/2009/12/pop-ate-my-heart-lady-gaga-her-videos-and-her-fame-monster.

Panagia, D. (2010): Lady Gaga and the Monstrous Art of Pop, The Contemporary Condition (March 20). Available: http://contemporarycondition.blogspot.com/2010/03/lady-gaga-and-monstrous-art-of-pop.html.

Phelan, P. (2004): Marina Abramović: Witnessing Shadows, Theatre Journal 56: 569-577.

Pryor, J.-P. (2010): Forever and a Day, Rokeby, Dazed and Confused (January 26).

Reardon, B. (2010): Haus of Gaga, i-D (Pre-Fall).

Robinson, L. (2010): Lady Gaga's Cultural Revolution, Vanity Fair (September).

Warhol, A. & Hackett, P. (1980): POPism: The Warhol Sixties. New York: Harcourt.

Wilcock, J. & Trela, C. (ed.) (2010): The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol. New York: Trela Media.

Wrbican, M. (2010); Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp / Andy Warhol, exhibition catalogue, 23 May-12 September 2010. The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.