Michael R. Taylor

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 1

GENESIS

(Part 4)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 45-54.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

IN THE MANNER OF DELVAUX

Despite Duchamp's prominent involvement in numerous Surrealist activities, including exhibition design, endless dinner parties, and "editorial responsibilities for the magazines View and VVV, around which the Surrealists hoped to regroup and disseminate new creative ideas, the artist initially lived a peripatetic life after returning from Europe in June 1942. He first stayed with the American poet Robert Allerton Parker at 1 Gracie Square in New York before moving on July 22 to Peggy Guggenheim's townhouse at 440 East Fifty-first Street, overlooking the East River, while the heiress spent the summer in the Massachusetts countryside with Max Ernst, her new husband. On October 1, Duchamp moved into the small apartment that adjoined the penthouse of the Austro-American architect Frederick Kiesler and his wife, Steffi, at 56 Seventh Avenue in Greenwich Village. A year later, Duchamp finally rented his own apartment at 210 West Fourteenth Street, in which he could work in solitude and begin obsessively to plan and eventually execute Étant donnés.

---- Also in 1942, Duchamp published a round photocollage, In the Manner of Delvaux (FIG. 1-A5), in the catalogue of the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition, held on the second floor of the former Whitelaw Reid mansion, an ornate, block-long brownstone located at 451 Madison Avenue in New York. The majority of works on view were made by members of the exiled European avant-garde, as suggested by the title, which refers to the immigration documents received by émigré artists such as Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Piet Mondrian on entering the United States. In retrospect, In the Manner of Delvaux, which is thought to have been included in the exhibition although no photograph of its display has come to light, can be seen as Duchamp's first deliberate allusion to Étant donnés. The artist would not begin constructing his secret project until four years later, but many of the themes and ideas embodied in the completed work are found in this 1942 collage—as well as in the artist's dense, disruptive installation of a maze of ordinary white string in the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition. The Surrealist-inspired fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli had asked Duchamp to install the show, which was sponsored by the Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies and organized for the benefit of war prisoners. First Papers of Surrealism included paintings and works on paper by nearly fifty artists, chosen by Duchamp, Breton, and Ernst to be displayed in an opulent, neo-Baroque interior ill-suited to the modern works. Duchamp's solution was to traverse the former drawing room of the mansion, which had been built in the 1880s to resemble a Florentine palazzo, with crisscrossing lines of taut white string that hung from the gilded moldings, crystal chandeliers, and Italianate painted ceiling to produce what amounted to a giant cobweb. Although the exhibition's press release mentioned that Duchamp had acquired "sixteen miles of string" for his cat's-cradle installation design, in the end no more than one mile of twine actually was strung around the vast interior space, although another mile was destroyed after an earlier effort to loop it over the chandeliers and it mysteriously caught fire.[107] The cause was never determined, but Duchamp ascribed it to spontaneous combustion. "I was just standing there," he later recalled, "when the black spots appeared and in another second glowed and burst into flame."[108]

FIG. 1-A5

Marcel Duchamp; In the Manner of Delvaux, 1942

Collage of tinfoil and photograph on cardboard

34 × 34 cm (133⁄8 × 133⁄8 inches)

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The Vera and Arturo Schwarz Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art

---- The opening invitation for the First Papers of Surrealism promised that the air would be permeated by the aromatic "smell of cedar," but the odor either was omitted or went unnoticed by the throngs of people attending the opening-night celebrations on October 14, 1942, none of whom reported an assault on their olfactory senses.[109] The reordering of aesthetic perception was achieved instead by Duchamp's tangled spider's web of string, which the artist may have intended as a reprise of Sculpture for Traveling (1917-18; fig. 1.28), a work composed of fragments of readymade rubber bathing caps in various colors. The caps were cut up and glued together in strips of different lengths that were stretched and suspended in his studio at random intervals, thus creating an installation whose shape could be changed at will. At the exhibition opening, the disorienting effect of the tangled string was amplified by the distracting sight and sound of schoolboys—including Carroll Janis, the eleven-year-old son of the art dealer Sidney Janis—playing ball loudly and causing a scene. Following his usual practice, Duchamp refused to attend the opening, but the day before he had instructed the children to play all evening without paying attention to the invited guests. When some bemused and rather disgruntled visitors asked the boys why they were disrupting the evening's events, they replied that "Mr. Duchamp told us we could play here."[110]

Fig. 1.28

Marcel Duchamp's Sculpture for Traveling, 1917-18

Henri-Pierre Roché (French, 1879-1959)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 1.29

Gallery view of First Papers of Surrealism with Marcel Duchamp's installation known as "Sixteen Miles of String," 1942

John D. Schiff (American, born Germany, 1907-1976)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 1.30

Marcel Duchamp with "Sixteen Miles of String" installation, 1942

Arnold Newman (American, 1918-2006)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll, 1945-72-20

---- Duchamp's strategy in the design of the 1942 exhibition in New York, similar to that of the one in 1938 in Paris, was to transform the existing space completely through a multisensory, nonlinear, interactive display that rendered it unrecognizable from its previous incarnation as a lavish Victorian mansion. The restricted field of vision afforded by the mesh of string that crisscrossed the room also points to Duchamp's cynical indifference to the works displayed on the walls and portable partitions; one critic memorably described how the installation "forever gets between you and the assembled art, and in so doing creates the most paradoxically clarifying barrier imaginable."[111] However, recent research has shown that press reaction to the show exaggerated the physical limitations of the string labyrinth, since the works of art were not completely blocked from view, as previously thought.[112] Photographs of the installation taken by John D. Schiff and Arnold Newman are also misleading (figs. 1.29 and 1.30), since the photographers stood behind the string to exaggerate the sense of an obstructed view. In reality, the string traversed the ceiling and hugged the edges of the room to demarcate the space into individual viewing zones. The installation recalled Breton's description of Duchamp's central grotto with its coal-sack ceiling in the 1938 Surrealist exhibition as a "zone of agitation which is situated at the confines of the poetic and the real," whose unsettling atmosphere was deliberately intended to be "as alien as possible from that of a so-called art gallery."[113] Of all the reviewers of the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition, Edward Alden Jewell, the art critic for the New York Times, was the only one to point out that those spectators who were "intrepid enough to reach closer proximity" to the paintings could do so "by means of certain strategic distributed apertures."[114] Nonetheless, the cobwebbed presentation can be understood as Duchamp's metaphorical statement on the defunct, corpselike status of modern painting, which he emphatically denounced in the New Yorker just ten days after the exhibition opened: "I don't believe in the sacred mission of the painter .... My attitude toward art is that of an atheist toward religion. I would rather be shot, kill myself, or kill somebody else, than paint again."[115]

---- Rather than create "the maximal obstacle between paintings and viewing space,"[116] as one art historian has recently claimed, Duchamp's string installation placed a physical and psychological barrier that determined the distance and angle at which the 105 works were viewed. The artist's intricate design of interwoven rigging thus denied the complete range of views that generally were available in museums and galleries, and instead fixed the viewing position of the spectator in much the same way as would the peephole device for Étant donnés. According to the avant-garde composer John Cage—who, along with his wife, Xenia Cage, met Duchamp in the summer of 1942 as a fellow houseguest at Peggy Guggenheim's townhouse—Duchamp's sustained interest in directing and controlling the spectator's viewpoint became "like a refrain" in his conversation: "He thought it would be interesting if artists would prescribe the distances from which their works should be viewed. He didn't understand why artists were so willing to have their works seen from any position. Of course, he was referring to the Étant donnés, without my knowing that the work existed."[117]

---- The twelve months that Duchamp spent as a houseguest of the Kieslers, beginning in October 1942, coincided with a commission from Peggy Guggenheim to visionary artist-architect Frederick Kiesler for the design and installation of her collection of abstract and Surrealist art in a gallery occupying a space that previously had housed two tailor shops. Located at 30 West Fifty-seventh Street in New York, Guggenheim's new gallery, Art of This Century, opened on October 20, 1942, just six days after Duchamp's "Six teen Miles of String" went on display. Kiesler and Duchamp had known each other since 1925 , when Fernand Léger introduced them at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, where Kiesler had presented his utopian City in Space (fig. 1.31).[118] This architectural project consisted of intersecting parallel lines and flat planes of color—reminiscent of the linear and geometrical elements found in the abstract paintings of Piet Mondrian, Theo Van Doesburg, and other De Stijl artists—that were used to represent an idealized three-dimensional city of the future, floating effortlessly in endless space.[119]

Fig. 1.31

City in Space, installation view, Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, Grand Palais, Paris, 1925

Frederick Kiesler (American, born Ukraine, 1890-1965)

---- Duchamp and Kiesler shared similar ideas on vision, perception, and the role of the spectator in the creative act, and their installation designs reveal closely aligned efforts to disrupt the viewer's senses.[120] It is possible that Duchamp, who was then living as a houseguest of the Kieslers, discussed issues of environmental exhibition display and spectatorship with the architect-theorist. Kiesler's efforts to create a unified architectural environment at Art of This Century, in which the works of art and the space surrounding them would be integrated in the viewer's perception, can be related to his earlier City in Space project, as updated through his subsequent understanding of Duchamp's work and ideas. In 1937, Kiesler had published an article on Duchamp's Large Glass, which he praised as a superb example of spatial painting: "It will not fit any description such as abstract, constructivist, real, super—and—surrealist without being affected. It lives on its own eugenics. It is architecture, sculpture and painting in ONE."[121] Duchamp did not share Kiesler's belief in the transcendental nature of painting and sculpture, but his disorienting "mile of string" installation at the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition had many affinities with the unorthodox system of coordinating architecture, painting, and sculpture at Art of This Century. Both installation designs attempted not only to dissolve the boundaries between art and architecture, but also to help the spectator recognize that he or she participates in the creative process by seeing and interpreting the works of art on view in an interactive environment that challenges the senses.

---- At Art of This Century, Kiesler disoriented the viewer by turning off the lights every two seconds, so that one side of the gallery. and then the other would be plunged into sudden darkness, while the sound of a steam engine trundling down a railway track further disoriented the visitor's perception. Once the lights came back on, Kiesler hoped the viewer would look at the paintings on display with heightened sensitivity, and he compared the alternating lighting system to blood flowing through the body's arteries: "It's dynamic, it pulsates like your blood. Ordinary museum lighting makes a painting dead."[122]

---- Although soon abandoned due to the high volume of complaints that Peggy Guggenheim received from irate visitors, Kiesler's lighting system recalls Duchamp's own experiments with optics and illumination, as in the 1938 Surrealist exhibition, where visitors made their way through the cavernous interior by means of a pocket flashlight. Duchamp's contribution to the 1942 exhibition, the small collage entitled In the Manner of Delvaux, consisted of an image revealed through a circular hole cut in a piece of cardboard covered with tinfoil (FIG. 1-A5). Through the aperture, the viewer espies a pair of woman's breasts reflected in an oval-shaped mirror nestled within a large knotted bow of white fabric and resting on a stone pedestal, which the title of the work suggests may be a detail from the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux's 1937 painting The Break of Day (L'Aurore) (fig. 1.32). On closer inspection, however, the image of the breasts is revealed to have been taken from a photograph of a nude woman rather than from Delvaux's painting, which was owned by Peggy Guggenheim and prominently displayed on a long vista at Art of This Century (fig. 1.33).[123] In Duchamp's collage, as in the final tableau-construction of Étant donnés, the viewer/voyeur enters a conspiratorial relationship with the artist, and together they instigate an act of visual penetration. In the case of In the Manner of Delvaux, the spectator looks through the tinfoil aperture at the cameo of Delvaux's painting as if peering through a keyhole into the privacy of a woman's boudoir.

Fig.1.32

Paul Delvaux (Belgian, 1897-1994); The Break of Day (L'Aurore), 1937

Oil on canvas, 120 × 150.5 cm (471⁄4 × 591⁄4 inches)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

Fig.1.33

Frederick Kiesler's Surrealist Gallery at Art of This Century, New York, 1942. At center is Paul Delvaux's painting The Break of Day (L'Aurore)

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

---- The title of In the Manner of Delvaux may provide a wider contextual framework for understanding Duchamp's nascent Étant donnés project, especially given Delvaux's intense fascination with the recumbent female nude, which had been a recurring motif in his work since the early 1930s. The inspiration for Delvaux's extended series of paintings of reclining nudes was his discovery of the Musee Spitzner at the Brussels Fair in 1932.[124] Originating as a fixed museum that opened in 1856 in Paris at the Pavillon de la Ruche, on the place du Château d'Eau (now the place de la République), Dr. Pierre Spitzner's Grand Musée Anatomique et Ethnologique (Great Anatomical and Ethnological Museum) was later transformed into a traveling fairground attraction featuring wax models of various human deformities, including a special exhibit of sexual diseases, as well as the preserved remains of conjoined twins, the skull of a criminal, a child's head preserved in a glass jar, a tanned human skin, and human and animal skeletons.[125] In Brussels, the museum was housed in a large shed decorated with red velvet curtains in the Foire du Midi. As Delvaux later recalled,

In the middle of the entrance to the museum was a woman who was the cashier, then on one side there was a man's skeleton and the skeleton of a monkey, and on the other side there was a representation of Siamese twins. And in the interior one saw a rather dramatic and territying set of anatomical casts in wax showing the horrors and torments of syphilis its—ravages and deformities. And all right in the midst of the artificial gaiety of the fair. The contrast was so striking that it made a powerful impression on me.[126]

---- What particularly caught Delvaux's attention was a didactic exhibition revealing the appalling symptoms of venereal diseases through life-size wax mannequins whose bodies bore the hideous side effects of syphilis and gonorrhea, along with genitourinary afflictions and congenital malformations, all depicted with shocking trompe l'oeil realism. The artist also was impressed by two realist paintings featuring nineteenth-century pioneers of modern medicine. The first depicted Jean Martin Charcot, the legendary professor of neuropathology at the Salpêtrière hospital for nervous diseases in Paris, examining an hysterical woman whose body had contorted itself into an arch, in the company of fellow doctors and medical students; the second showed the world-renowned French chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur at the bedside of a sick child.[127]

---- The profound impact of this popular anatomical museum, with its extraordinary spectacle of realist paintings, skeletons, and life-size wax mannequins, can be discerned in Delvaux's The Break of Day (L'Aurore), which explores a similar dialogue between reality and artifice, the physical and the imaginary, the banal and the poetic, and Eros and Thanatos. However, there was another exhibit at Spitzner's itinerant educational museum that can shed light on the Belgian artist's haunting series of reclining nudes—as well as on Duchamp's Étant donnés—namely, La Vénus endormie (The Sleeping Venus), a morbid tableau vivant that featured a wax mannequin of a sleeping woman clothed in a white satin gown and housed in a glass and wooden case (fig. 1.34).[128] What startled and unnerved the fairground strollers in Brussels, including Delvaux himself, was the heaving of her chest, achieved by means of a hidden motor, which gave the wax model the illusion of living breath.[129] The discovery of the Musée Spitzner marked a critical turning point in Delvaux's art. The mechanized Venus, in particular, would provide an important catalyst for numerous paintings of frozen, inanimate nudes, all of which are imbued with a claustrophobic, dreamlike atmosphere. The stiff, artificial poses and trancelike attitudes of these phantasmagorical figures re-create Delvaux's memory of the breathing wax simulacrum, which, like the female statue in the Pygmalion myth, owes its human existence to the imagination and desires of the artist, who himself often plays the role of a voyeur in his own paintings.

Fig.1.34

La Vénus endormie (The Sleeping Venus) of the Musée Spitzner, detail (photographed c. 1978)

Musée de la Médecine—IRMA (Fonds Spitzner)

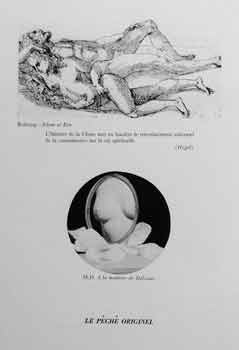

---- In the Manner of Delvaux also was reproduced in the First Papers of Surrealism catalogue, in a chapter entitled "On the Survival of Certain Myths and On Some Other Myths in Growth or Formation." Although the catalogue is attributed to Breton, it is likely that Duchamp had some input in its design and layout, especially regarding the eventual placement of his photographic collage, which appears above the heading "Le Péché originel" in a section devoted to Original Sin (fig. 1.35). Duchamp's collage is shown in a cropped version that reproduces only the tondo with the mirror reflecting the bared breasts and the knotted-bow arrangement. Above Duchamp's work is Hans Baldung Grien's harmonious drawing Nude Couple at Rest (1527), identified in the catalogue as Adam et Eve, with a caption that quotes Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's The Fall of Man: "L'histoire de la Chute met en lumièere Ie retentissement universel de la connaissance sur la vie spirituelle" (The history of the Fall sheds light on the universal theme of the birth of spiritual life).[130] Seen together, the images of the slumbering, postcoital Adam and Eve and the porthole view of the "breasts bathing their mirror," as Éluard described Delvaux's work,[131] prefigure the subject matter and viewing apparatus of Étant donnés, whose subtitle — 1° la chute d'eau, 2° Ie gaz d'éclairage [1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas] — is uncannily reflected in Hegel's text, with its direct reference to the waterfall (la Chute) and its allusion to the illuminating gas through the word lumière.[132]

Fig. 1.35

Marcel Duchamp's collage In the Manner of Delvaux, published in the exhibition catalogue First Papers of Surrealism (New York, 1942)

---- The catalogue for First Papers of Surrealism confirms that Duchamp was thinking about Étant donnés as early as 1942, even if he had not yet formulated the exact composition and scope of the project. In his photocollage In the Manner of Delvaux, the reflection of a female torso in a mirror suggests that the artist's original concept, seen again in the 1948 drawing Réflection à main (Hand Reflection; FIG. 1-A7), was to create a narcissistic perspective in which the reclining nude would hold up a looking glass to the spying viewers, who thus would see themselves in the mirror and become selfconsciously aware of being caught in a voyeuristic act.[133] The tinfoil used to frame the collage's aperture further suggests that Duchamp initially considered a metallic viewing device, as opposed to a weather-beaten - wooden door, for Étant donnés.

FIG. 1-A6a

Marcel Duchamp and Frederick Kiesler; Twin-Touch-Test, 1943

Back cover and last page of VVV Almanac for 1943, March 1943

Paper-bound periodical with chicken-wire inserts

27.9 × 21.4 cm (11 × 87⁄16 inches)

Frederick Kiesler (American, born Ukraine, 1890-1965)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Carl Zigrosser

FIG. 1-A6b

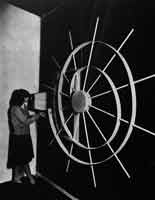

---- Perhaps more significantly, the circular nature of the framing mechanism evokes the kinetic display designed in 1942 by Frederick Kiesler for an installation of Duchamp's Boîte-en-valise at Art of This Century (fig. 1.36).[134] The spectator viewed Duchamp's work by looking through a small, lenslike opening while turning a large, spiral-shaped wheel that resembled the kind of wooden ship's wheel used to steer and change direction at sea. Peering through the peephole and gently spinning the wheel, the viewer observed fourteen feuilles libres (loose folders) featuring reproductions of the artist's most famous works as they passed before the window in continuous succession through a rotating system, like a Ferris wheel laden with works of art.[135] This mechanical apparatus for showing reproductions from the Boîte-en-valise probably helped Duchamp to estab- lish the viewing position for Étant donnés, in which only one viewer at a time can look through the peepholes into the interior space containing the artist's enigmatic scene.

Fig. 1.36

Berenice Abbott. Frederick Kiesler's viewing mechanism for Marcel Duchamp's Boîte-en-valise, Kinetic Gallery, Art of This Century, 1942.

---- As we have seen, Kiesler and Duchamp shared an interest in unconventional installation techniques that invited active participation by the viewer, as well as shop window displays and optics.[136] This interactive role is perhaps best exemplified by Kiesler's mechanical device for displaying reproductions from the Boîte-en-valise, which placed the viewer in complete control of the speed and selection of each image through a turn of the wheel. Growing out of his earlier ideas for a "vision machine," which Kiesler developed at Columbia University between 1938 and 1942, the display mechanism anticipates the pair of holes in the wooden door of Duchamp's Étant donnés—which similarly makes the work available to a single viewer—and underlines the two men's shared interest in the dynamics and structure of vision and perception.

---- Kiesler and Duchamp's humorous joint design for the back cover of the second and third issues of VVV, for example, published in 1943 as an almanac, illustrates their desire to engage the viewer as an active participant in the creative act. This magazine was first published in June 1942, coinciding with Duchamp's arrival in New York. Its curious title was clarified by André Breton in a statement published on the title page of the initial issue, in which he explained that the initials stood for the reconciliation of "the View around us" with "the View inside us," but more exactly for "Victory over the forces of regression and death unloosed at present on the earth—victory over fascism." After the first issue, Duchamp joined Breton and Ernst as an editorial advisor on the publication, which was edited by the American artist David Hare under their close supervision, thus ensuring that VVV introduced a wide range of Surrealist themes to American audiences. The back-cover design for the 1943 almanac consists of a cutout profile of a nude woman's torso drawn by Duchamp, with chicken wire inserted in the opening. Readers are encouraged to perform the "Twin-Touch-Test," that is, to place their hands on either side of the chicken wire and then rub up and down until they received an "unusual feeling of touch" in their fingertips (FIGS. 1-A6a and 1-A6b), a tingling sensation akin to orgasm. To guide them in this intimate self-examination, on the last page of the azine the artists included a photograph of Peggy Guggenheim's daughter, Pegeen Vail—visible through the chicken wire of the back cover—who appears to be praying, although on closer inspection her revealed to be on either side of a large wire screen. WMe her eyes are rolled back in a saintly expression of piety, this image of spiritual ecstasy is clearly aligned with the masturbatory symbolism of the back cover and the accompanying written instructions.

![Marcel Duchamp: Réflection à main (Hand Reflection), 1948 Marcel Duchamp: Réflection à main (Hand Reflection), 1948 /// Original painting from the deluxe edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise)(From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in Valise]), no. XVIII/XX --- Pencil on paper with collage of a circular mirror covered by a circular cutout of black paper, mounted under Plexiglas, 23.5x16.5 cm --- Private collection](33/F-A7-Marcel-Duchamp-Reflection-a-main-Hand-Reflection-1948.jpg)

FIG. 1-A7

Marcel Duchamp; Réflection à main (Hand Reflection), 1948.

Original painting from the deluxe edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise)(From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in Valise]), no. XVIII/XX.

Pencil on paper with collage of a circular mirror covered by a circular cutout of black paper, mounted under Plexiglas,

23.5 x 16.5 cm (91⁄4 x 611⁄2 inches)

Private collection

---- In the early 1940s, Duchamp began to move away from his initial idea of a lifelike female automaton that could be activated, much like Spitzner's hyperrealist Sleeping Venus, through a mechanical device. The artist instead began to explore the idea of a three-dimensional tableau-construction, with the mannequin placed in a grottolike environinent similar to the one he had constructed for the 1938 Surrealist exhibition in Paris, which had featured a pond fringed with plants and a floor covered in leaves. As I have argued, this shift was inspired in part by Bellmer's doll photographs, as well as by Delvaux's mirror reflection of a woman's breasts and upper torso in The Break of Day, which had been prominently displayed on a concavely curved wall at one end of the Surrealist gallery at Art of This Century, where it seemed to float within Kiesler's unified spatial environment. Duchamp probably was drawn to Delvaux's painting due to their shared interest in the motif of the femme-arbre (literally, tree-woman), derived from the legend in Ovid's Metamorphoses of Phaeton's mourning sisters, who are transformed into poplar trees.[137] These four archaic fertility deities, whose lower bodies have metamorphosed into tree trunks that literally root them in the earth, recall Duchamp's earlier description, in the notes published in The Green Box, of the Bride of The Large Glass as an "arbre type" (arbor type).[138] At some point, however, the bared breasts reflected in the oval looking glass of Delvaux's painting coalesced in Duchamp's mind with Kiesler's ingenious optical apparatus for viewing his Boîte-en-valise to create a forbidden and transgressive image of a nude body, viewed through a pair of peepholes, that would haunt Duchamp's imagination for the rest of his life. As in Kiesler's space-saving design for displaying Duchamp's works in the kinetic gallery at Art of This Century, which was compared at the time with Coney Island peep shows,[139] the viewer plays an active role in Étant donnés, since the work is visible only to those who choose to peer through the sight holes in the sturdy wooden door.

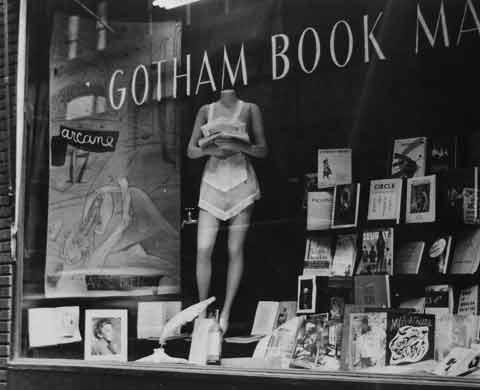

Fig. 1.37

Maya Deren. Marcel Duchamp's, installation Lazy Hardware, Gotham Book Mart, New York, 1945

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- The artist's inclusion of In the Manner of Delvaux in the First Papers of Surrealism was one of several carefully chosen instances after World War II when he made deliberate allusions in public exhibitions, objects, and catalogues to his secret work on Étant donnés, which was then in the early planning stages. For example, Duchamp's 1945 window display Lazy Hardware featured a headless mannequin wearing a skimpy white apron, with a faucet attached to her right thigh like a drooping but not dripping penis (see figs. 1.37 and 1.38).[140] In her hands, the mannequin protectively holds two open, turned-down copies of Breton's book against her chest, while behind her right foot is a small card labeled "Lazy Hardware," after an aphorism Duchamp had first used in the 1926 short film Anémic cinéma, which he made with Man Ray and Marc Allégret: "Parmi nos articles de quincaillerie parasseuse, nous recommandons un robinet qui s'arrête de couler quand on ne l'écoute pas" (Among our articles of lazy hardware we recommend a faucet which stops dripping when nobody is listening to it).[141] The stopped faucet in Lazy Hardware hints at the idea of running water, thus anticipating the sparkling waterfall in the completed assemblage of Étant donnés. Like Duchamp's other shop-window displays[142] and exhibition installations—as well as the erotic objects he made using cast body parts derived from the construction process of Étant donnés, to be discussed in the next chapter—the full implications of Lazy Hardware would not be understood until after the posthumous unveiling of his brightly lit diorama.

Fig.1.38

Maya Deren. Marcel Duchamp's, installation Lazy Hardware, Gotham Book Mart, New York, 1945

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 45-54.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[107] Sec Robert M. Coates, "The Art Galleries: Sixteen Miles of String," New Yorker, vol. 18, no. 37 (October 31, 1942), p. 72. Duchamp discussed the spontaneous combustion of the first web of string as well as the ideas behind the exhibition design in an interview with Harriet, Sidney, and Carroll Janis in the spring of 1953; typescript, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives.

[108] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Rudi Blesh, Modern Art USA: Men, Rebellion, Conquest, 1900-1956 (New York: Knopf, 1956), p. 200.

[109] Filipovic, Marcel Duchamp on Display, p. 9.

[110] See Blesh, Modern Art USA, p. 201. In a letter dated October 15, 1942, Duchamp told his great friend and patron Katherine Dreier that he had not attended the opening, as was his custom, "but reports indicate that the children played with great gusto"; Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Collection of American Literature, Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Societé Anonyme Archives.

[111] Edward Alden Jewell, "Surrealism in Current Shows," New York Times, October 18, 1942, section 10, p. 9.

[112] As John Vick has argued, previous scholars including T.J. Demos and Lewis Kachur have failed to question the accepted wisdom that the string placed an insurmountable barrier between the viewer and the works of art on display. Using John D. Schiff's photographs of Duchamp's webbed installation as his guide, Vick returned to the second-floor drawing room of the Whitelaw Reid mansion, where he discovered that the artist's maze could not have obstructed the viewing conditions to the degree that was described in press reports of the time. He also noted that the staged and overly dramatic photographs of the exhibition used extreme angles and framing devices to exacerbate the viewer's sense of disorientation, by focusing on the string rather than the works of art on display. According to Vick's synopsis, the string was confined to the ceiling space and the gaps between the partition walls that had been installed to maximize the hanging area for the paintings, while the rest of the large room, including the partitions, was open to free and uninterrupted circulation. See Vick, "A New Look: Marcel Duchamp, His Twine, and the 1942 First Papers of Surrealism Exhibition," Tout-fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, www.toutfait.com (accessed October 25, 2008).

[113] Andre Breton, "Devant Ie rideau," in Le Surréalisme en 1947, exh. cat., Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme (Paris: Galerie Maeght, 1947), pp. 13-14.

[114] Edward Alden Jewell, "Surrealists Open Display Tonight," New York Times, October 14, 1942, p. 26.

[115] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in "Artist at Ease," New Yorker, vol. 18, no. 36 (October 24, 1942), p. 13.

[116] T.J. Demos, The Exiles of Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), p. 196 (emphasis in the original).

[117] John Cage, quoted in Moira Roth and William Roth, "John Cage on Marcel Duchamp," Art in America, vol. 61, no. 6 (November-December 1973), p. 75.

[118] See Maria Bottero, "Kiesler Observed by Lilian Kiesler," in Bottero, ed., Frederick Kiesler: Arte, architettura, ambiente, exh. cat., Galleria della Triennale di Milano (Milan: Electa, 1995), p. 209.

[119] See Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "Frederick Kiesler and the Bride Stripped Bare ...," in Yehuda Safran, ed., Frederick Kiesler, 1890-1965, exh. cat. (London: Architectural Association, 1989), p. 62.

[120] For more on the shared affinities between Kiesler and Duchamp, see Dieter Daniels, "Points d'interférence entre Frederick Kiesler et Marcel Duchamp," in Chantal Beret, ed., Frederick Kiesler: Artiste—architecte, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1996), pp. 119-30.

[121] Frederick Kiesler, "Kiesler on Duchamp," Architectural Record, vol. 81, no. 5 (May 1937), p. 54 (emphasis in the original). Duchamp wrote to the architect to thank him for "the spirit of the article, then your reinterpretation and the presentation of your ideas! Thank you for having wanted to look at the glass with such attention and to clarify points that few people know about .... I am sending you a copy [of The Green Box] by the next post, hoping that in glancing through it you will see how right you are"; quoted in Gough-Cooper and Caumont, entry for June 25, 1937, Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), unpaginated.

[122] Frederick Kiesler, quoted in Newsweek, "Isms Rampant: Peggy Guggenheim's Dream World Goes Abstract, Cubist, and Generally Non-Real," vol. 20, no. 18 (November 2, 1942), p. 66.

[123] Although the exact photograph used for the collage remains unknown, the model's torso and firm, nubile breasts recall Man Ray's photographs of Suzy Solidor, taken about 1929-30, including an untitled work in which a nude Solidor stands beside a leering man, dressed in a suit and tie and smoking a cigarette, who stares intently at her breasts. This photograph, which bears a strong resemblance to the cropped, circular image used in Duchamp's collage, was printed in 1998 by Jacques Faujour and Daniel Valet from Man Ray's original negative, and was reproduced for the first time in Emmanuelle de I'Ecotais and Alain Sayag, eds., Man Ray, la photographie à I'envers, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou/Éditions du Seuil, 1998), p. 75. Peggy Guggenheim had purchased the painting in June 1938 from the Belgian Surrealist artist and dealer E.L.T. Mesens; see Angelica Zander Rudenstine, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and Abrams, 1985), p. 215.

[124] See Gisèle Ollinger-Zinque, "The Making of a Painter-Poet," in Paul Delvaux, 1897-1994, exh. cat., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels ([Belgium]: Blondé, 1997), p. 17.

[125] For an excellent discussion of the history of the various incarnations of Spitzner's popular anatomical museum, and its heady mixture of public pedagogy, popular entertainment, commerce, and art, see Kathryn A. Hoffmann, "Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground: The Spitzner, Pedley and Chemisé Exhibits," Early Popular Visual Culture, vol. 4, no. 2 (July 2006), pp. 139-59.

[126] The artist recounted his vivid memories of the Musée Spitzner in a 1973 interview with Renilde Hammacher that was published in Émile Langui, ed., Paul Delvaux, exh. cat. (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans van Beuningen, 1973), p. 14 (my translation).

[127] Ibid, p. 19. According to Kathryn A. Hoffmann, the medical scene featuring Pasteur showed him inoculating a Russian woman, rather than tending to the sick child as Delvaux remembered; see Hoffmann, "Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground," p. 144.

[128] Several undated photographs of Spitzner's La Vénus endormie are reproduced in Philippe Blon et al., eds., Voir—La Collection Spitzner (Tressan, France: Antigone, 1988), pp. 16-18.

[129] Suzanne Lilar, a visitor to Spitzner's museum when it traveled to Brussels, later recalled the illusion of artificial breath emanating from the mechanized wax model: "I did not miss the opportunity to go and contemplate this wax chest that rose regularly as if it were the result of breath"; quoted in Hoffmann, "Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground," pp. 141-42. The explanatory catalogue that was given to every visitor praised this "Reclining Venus, modeled from life. Artistic masterpiece that was awarded two medals at the Vienna exhibition. The first ... for the remarkable progress it achieved in the art of modeling; the second for the ingenious mechanism inside the breast giving the subject the appearance of being alive"; Grand Musée anatomique du Docteur Spitzner, exh. cat. (Brussels: Ixelles Museum, 1979), p. 4, no. 202.

[130] See Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Logic of Hegel, Translated from the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences, trans. William Wallace, 2nd rev. and exp. ed. (1931; London: Oxford University Press, 1892), p. 54.

[131] Paul Éluard, "Exile," in Art of This Century: Objects, Drawings, Photographs, Paintings, Sculpture, Collages, 1910 to 1942, ed. Peggy Guggenheim (New York: Art of This Century, 1942), p. 130. Dedicated to Paul Delvaux, Éluard's 1940 poem takes its point of departure from the Belgian artist's The Break of Day (L'AuIrore), with its "great immobile women" who are "left to their fate to know nothing but themselves."

[132] As Thomas Singer has pointed out, the French word connaissance in this context may refer to carnal knowledge, thus providing another reference to Étant donnés Unfortunately, Singer translates Hegel 's text into English and therefore misses the crucial link between Hegel's quote and the subtitle of Duchamp's secret work; see Singer, "In the Manner of Duchamp, 1942-47: The Years of the 'Mirrorical Return,'" Art Bulletin, vol. 86, no. 2 (June 2004), p. 351.

[133] Herbert Molderings has perceptively connected Hand Reflection with the allegorical tradition of truth in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French painting—seen for example in Jules-Joseph Lefebvre's 1870 painting La Vérité (The Truth)—a tradition that Duchamp surely would have been aware of; see Molderings, "Un Cul-de-lampe: Réflexions sur la structure et l'iconographie d' Étant donnés," Étant donné Marcel Duchamp, no. 3 (2001), pp. 92-111.

[134] Peggy Guggenheim purchased her deluxe edition of the Boîte-en-valise (numbered I/XX) in January 1941 from Duchamp, with Henri-Pierre Roché acting as intermediary; see Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, p. 258.

[135] An ambitious analysis of Kiesler's designs for displaying works of art at Art of This Century, including Duchamp's Boîte-en-valise, is found in Don Quaintance, "Modern Art in a Modern Setting: Frederick Kiesler's Design of Art of This Century," in Susan Davidson and Philip Rylands, eds., Peggy Guggenheim and Frederick Kiesler: The Story of Art of This Century (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications; Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection; Vienna: Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, 2004), pp. 207-73.

[136] Both Duchamp and Kiesler designed shop-window displays and explored the erotic, aesthetic, and psychological dimension of window shopping—with its overtones of voyeurism—in terms of looking through the glass showcases at commodities and seeing other shoppers inside, as well as in terms of fetishistic identification with the goods on display. In a note written in 1913 but not published until 1967, Duchamp unmistakably alluded to the forbidden erotic sensation involved in the "interrogation" of reflective shop windows, which would later inform his decision to create The Large Glass on two transparent panes of glass; see Marcel Duchamp, In the Infinitive: A Typotranslation by Richard Hamilton and Ecke Bonk of Marcel Duchamp's White Box, trans. Jackie Matisse, Richard Hamilton, and Ecke Bonk (Northend, UK: Typosophic Society, 1999), p. 5. In 1930, Kiesler published his radical ideas on the application of modern design techniques to shop-window display, which can be seen as the basis for nearly all of his subsequent design ideas, including exhibition installation; see Frederick Kiesler, Contempomry Art Applied to the Store and Its Display (New York: Brentano's, 1930).

[137] Ovid Metamorphoses 2.340-66.

[138] Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds., Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du Sel) (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 42.

[139] Time magazine reported that gallery-goers entered "a kind of artistic Coney Island. Here are shadow boxes, peepholes, in one of which, by raising a handle, is revealed a brilliantly lighted canvas by Swiss painter Paul Klee. Another peep show, manipulated by turning a huge ship's wheel, shows a rotating exhibit of reproductions of all the works ... by screwball Surrealist Marcel Duchamp"; see "Inheritors of Chaos," Time, November 2, 1942, p. 47. Another reviewer described the kinetic gallery as "a pennyarcade peep show except that you didn't need the pennies"; see "Isms Rampant," p. 66.

[140] Lazy Hardware was part of a large window display, on which Duchamp collaborated with Roberto Matta, André Breton, and Isabelle Waldberg, and which initially was commissioned by the book publisher Brentano's for its store on Fifth Avenue, where "it remained twenty minutes in their window, attracting crowds and protests" from the League of Women, before being taken down and moved to the Gotham Book Mart, where it remained for the week of April 19-26, 1945; "View Listens," View, ser. 5, no. 2 (May 1945), p. 41. While the display was at the Gotham Book Mart, John S. Sumner, representing the Society for the Suppression of Vice, objected to the sexual content of Matta's poster featuring an exposed female breast. The offending body part was subsequently covered over by Sumner's business card and a second card beneath it, bearing the word "censored" in large capital letters; see Charles F. Stuckey, "Duchamp's Acephalic Symbolism," Art in America, vol. 65, no.1 (January/February 1977), p. 95.

[141] Duchamp, Salt Seller, p. 106.

[142] See Thomas Girst, "Those Objects of Obscure Desires: Marcel Duchamp and His Shop Windows," in Christoph Grunenberg and Max Hollein, eds., Shopping: A Century of Art and Consumer Culture, exh. cat., Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Tate Gallery Liverpool (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2002), pp. 143-46. As Girst has suggested, the shop-window display that Duchamp designed for Breton's book Le Surréalisme et le peinture at Brentano's bookstore in New York in November 1945 also contains clear allusions to Étant donnés. Duchamp collaborated on this design with the artists Isabelle Waldberg and Enrico Donati, but as Waldberg wrote at the time, "Naturally Marcel has done everything, the whole design, and the whole execution"; ibid., p. 44. The shop-window display contained a half-torso mannequin made of chicken wire, thus connecting it to the "Twin-Touch-Test" in VVV. Other items that prefigured Étant donnés included paper strips that fell from the ceiling like a cascading waterfall and a suspended wire sculpture of a female torso by Waldberg, whose pose corresponded to the preliminary studies for Duchamp's mannequin, as well as its final configuration; ibid.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES