Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Michael R. Taylor

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 2

CONSTRUCTION (Part 4)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 100-107, 124-126. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 ---- Part 5

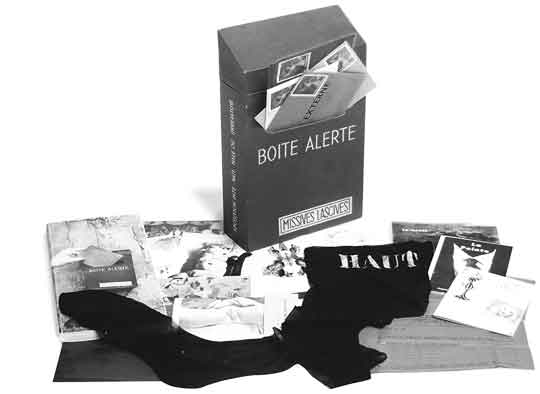

E.R.O.S.

Another important landmark on the road to the completion of Étant donnés was Duchamp's participation in the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme, dedicated to Eros as indicated by the uppercase letters in the show's title, which opened in December 1959 at the Galerie Daniel Cordier on the rue de Miromesnil in Paris. As with the 1947 Surrealist exhibition, Duchamp played a central role in both the layout of the show and the design of the catalogue, entitled Boîte alerte (Emergency Box). Made in collaboration with the Canadian artist Mimi Parent,[158] the deluxe edition of the catalogue was housed in a green cardboard box designed to resemble a mailbox filled with missives lascives (lascivious missives) and deliberately evoking Duchamp's Green Box (FIG. 2a.52). The letterbox (boîte à lettres) contained several disturbing images (fig. 2.44a,b), including a hand-tinted postcard by Bellmer of his 1937 photograph of one of his flushed and tumescent poupées, and an anonymous photograph entitled Le [sic] Cadenas de chasteté (Chains of Chastity) of a woman whose vagina had been sewed shut and padlocked, an image that may relate to Duchamp's Wedge of Chastity. On a lighter note, the deluxe edition of the box also included a pair of "male" and "female" potholders that Duchamp, characteristically understating their erotic content, titled Couple of Laundresses' Aprons (FIG. 2a.53). These works were executed in Paris by Mimi Parent in an edition of twenty, made under Duchamp's direction and based on a pair of tartan potholders that he had found "readymade" in New York. The humorous oven mitts were fitted with pouches that when lifted or unzipped revealed under one an erect cloth phallus and under the other a clump of fur representing female pubic hair — thus recalling the fur pouches. known as sporrans, that are worn at the front of the kilt in the traditional dress of men from the Scottish Highlands. The fur may also relate to Duchamp's earlier pun "Abominable Abdominal Furs."[159]

FIG. 2a.52

Marcel Duchamp

Boîte alerte (Emergency Box), 1959

Deluxe edition of catalogue for Exposition Intemationale du Surréalisme

Cardboard box containing paperbound catalogue and ephemera, postcards, notes,

envciopes, portfolio of artists' prints, printed nylon stocking, and 45 rpm record

28,6 × 18,1 × 6,4 cm (111⁄4 × 71⁄8 × 21⁄2 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse

in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

![Le [sic] Cadenas de chasteté (Chains of Chastity) Postcards from Boîte alerte (Emergency Box), deluxe exhibition catalogue. Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surrélisme, Galerie Daniel Cordier, Paris, 1959. Le [sic] Cadenas de chasteté (Chains of Chastity).](38/f-44b-Postcards-from-Boite-alerte-Emergency-Box.jpg)

Fig. 2.44a,b

Postcards from Boîte alerte (Emergency Box), deluxe exhibition catalogue. Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surrélisme, Galerie Daniel Cordier, Paris, 1959 (see FIG. 2a.52)

Top: one of Hans Bellmer's poupées from 1937

Bottom: Le [sic] Cadenas de chasteté (Chains of Chastity)

FIG. 2a.53

Marcel Duchamp

Couple of Laundress's Aprons, 1959

Imitated rectified readymade: two potholders (male and female),

included in Boîte alerte (Emergency Box)

Male figure: cloth, 20,3 × 17,7 cm (8 × 615⁄16 inches)

Female figure: cloth and fur, 20,5 × 19,8 cm (81⁄16 × 713⁄16 inches)

Collection of the Honorable and Mrs. Joseph P. Carroll, New York

---- Duchamp and Andre Breton, with the assistance of José Pierre and Pierre Faucheux (designed the labyrinthine interior space of the gallery, and once again the artist used a Surrealist exhibition to experiment with key ideas behind Étant donnés, in this case the artificial and somewhat theatrical staging of scopophilic pleasure, as well as the interactive role of the spectator in "completing" the work of art.[160] Duchamp understood the viewer/voyeur to be a crucial component in all art, but especially in Étant donnés, where the illusionistic transformation from appearance to apparition takes place in the mind of the viewer as he or she peeps through the two holes that the artist bored in the wooden door.

---- Designed as a "theater of provocations and prohibitions" to celebrate eroticism's "fundamental need for transgression," the sensory overload of the 1959 Surrealist exhibition surpassed that of any of Duchamp's previous installations.[161] In Breton's preface to the exhibition catalogue, he invoked Georges Bataille's well-known investigation of eroticism, in which the dissident Surrealist opposed mere "animal sexuality" to an inner experience of eroticism, "that part of man's consciousness which calls his own being into question."[162] Rejecting the furtive, shame-ridden, and inhibited sexuality that Bataille had identified in his classic conjunction of eroticism and death, Breton and Duchamp's exhibition design instead venerated eroticism as "mankind's greatest mystery."[163] In his catalogue introduction, Breton quoted from the recently published steamy sex romp Emmanuelle, which claimed that erotic art was "the only art which measures up to man and space, the only one capable of leading him beyond the stars, just as the figures fashioned of ochre and smoke opened the walls of their caverns on to the future."[164]

---- Breton expressed the Surrealist group's hope that within the exhibition space an "organic liaison" would occur between the artist and the viewer, since the works on display — including Duchamp's With My Tongue in My Cheek, used as the frontispiece to the catalogue — were conceived not as "objects" but rather as evocative "suggestions" that would encourage the viewer to discover hitherto unknown or repressed aspects of his or her self.[165] Breton even singled out the "entirely dissimilar" works of Giorgio de Chirico and Duchamp, whose "unabated power upon Surrealism" came, he argued, from their common interest in a "veiled" form of eroticism.[166] While Breton considered eroticism an almost sacred mystery, Duchamp viewed it as a liberating force that freed him from the usual coordinates of space, time, and logic, as well as from the normative limits of representation and sexuality. This principle is perhaps best exemplified in his erotic objects made from mold fragments and cast body parts, and in their photographic depictions (such as the inverted Female Fig Leaf; FIG. 2a.32), which destabilized fixed notions of the appearance of male and female genitals.

---- In a 1959 interview with Richard Hamilton and the art historian Charles Mitchell, Duchamp explained that "eroticism is a subject very dear to me," adding, "in fact, I thought the only excuse for doing anything is to introduce eroticism into life."[167] In a subsequent interview with the art critic and writer Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp refused to give a personal definition of eroticism, but remarked that "basically it's really a way to try to bring out in the daylight things that are constantly hidden — and that aren't necessarily erotic — because of the Catholic religion, because of social rules. To be able to reveal them, and to place them at everyone's disposal — think this is important because it's the basis of everything and no one talks about it."[168] Almost his entire oeuvre is permeated by a strong sexual charge, and there can be no doubt that eroticism also strongly motivated Duchamp in his secret work on Étant donnés, as well as his production of its related erotic objects and studies. Indeed, the artist's prophetic statement to Cabanne regarding the illumination of "things that are constantly hidden" can be understood in retrospect as alluding to his underground activity on the erotic assemblage, as well as presaging the posthumous unveiling of Duchamp's voyeuristic final masterwork in 1968.

---- As Breton clearly understood, Duchamp was the perfect artist to codesign the 1959 exhibition, known as E.R.O.S., and the resulting idiosyncratic, multisensory installation did not disappoint. As in the 1947 Surrealist exhibition, the intention was to challenge and interrogate visitors' understanding of reality by giving free rein to their imaginations, which this time around would be stimulated by desire and eroticism, rather than fear. Details of E.R.O.S., which was broken down into a series of interconnected erogenous zones, are worth recounting, given Duchamp's intense involvement with the installation design and its anticipation of the voyeuristic viewing apparatus of Étant donnés.[169]

---- The exhibition's antechamber was remembered by the Nouveaux Réaliste artist Daniel Spoerri as "a sort of abstract slit,"[170] through which you entered the first of a series of interconnected galleries whose undulating walls were lined with pink velvet, rhythmically "breathing" in and out thanks to hidden air pumps.[171] Suspended from the ceiling, in all her fetishistic glory, was Hans Bellmer's "scandalous" abject Doll, with its implicit connection to the recumbent mannequin in Étant donnés (see figs. 2.45 and 2.46). As Alyce Mahon has related, the fragmented, multilimbed Doll hung from the ceiling "like a Sadean victim, her body manipulated and contorted to appear as a double-legged creature, the monstrosity of her form only offset by two pairs of girlish shoes and socks and the vacant stare of her face."[172] The voyeuristic spectacle of Doll viewed from below was enhanced when Duchamp, following the German artist's directives, gave specific instructions to Pierre Faucheux to embed three large mirrors in the thick layer of fine sand that covered the floor of the entrance gallery. Each mirror was carefully placed underneath Bellmer's suspended work to provide the viewer unprecedented access to the complex anatomy of her multiple limbs, appendages, and orifices, reflected in triplicate. The disconcerting display engendered three different views of the doll's sex, and offered visitors the voyeuristic thrill of seeing Bellmer's perverse poupée from unfamiliar and intimate angles, while at the same time threatening them with exposure as they looked at such a forbidden object of desire.

Fig. 2.45

Pablo Volta (Argentinean, 1926-2011)

André Breton (in foreground) and José Pierre,

with Hans Bellmer's construction La Poupée (The Doll),

at the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surrélisme, 1959

Fig. 2.46

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

La Poupée (The Doll), 1932-45

Painted wood, hair, shoes, and socks, 61 × 170 × 51 cm (24 × 667⁄8 × 201⁄8 inches)

Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

---- Adjacent to Bellmer's work were a metaphysical painting by Giorgio de Chirico and a pair of floating, shapely pink lips that Duchamp officially intended to evoke the breath of Flora in Sandro Botticelli's Primavera (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), while also alluding to the breathing walls and ceiling. The elongated satin lips may have functioned further as Duchamp's protest at the continued exclusion of Salvador Dalí's work from Surrealist exhibitions, despite the enormous influence· of his paintings and objects, such as the Mae West Lips Sofa, on the movement in the 1930s. At the end of the entrance portal, visitors passed through a pearl curtain in an ogival door — which the Surrealist artist and historian Robert Benayoun memorably recalled as "a 'vaginal' door with beads of dew"[173] — and then followed a series of organic, intrauterine passageways, thus anticipating Niki de Saint-Phalle's back-to-the-womb sculpture Hon (She), of 1966, in which visitors entered the gaping vagina of an architecturally scaled pregnant woman lying on her back with her legs open, as if ready for a gynecological examination (fig. 2.47). The walls and ceilings were swathed in deep, light-absorbing, moss-green velvet, whose cavernous, grotto like effect was enhanced by the use of sand-covered floors and stalagmite- and stalactitelike projections.[174]

Fig. 2.47

Niki de Saint-Phalle (French, 1930-2002)

Hon (She),1966

Large-scale sculpture, c. 6 × 28 m (236 × 1102 inches)

Moderna Museet. Stockholm

---- Narrow, winding corridors, some shrouded in darkness, others filled with works of art from floor to ceiling, led to the two rooms at the heart of the exhibition, the first of which was the appropriately named Fetish Chamber, a cryptlike alcove covered in black fur that was designed by Mimi Parent and included small-scale mixed-media constructions, objects, and fetishes. In an erotic finale, the visitor arrived in a square, open room with blood-red satin walls, containing at one end Cannibal Feast by the Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim, an extraordinary tableau featuring a table on which, at the gala opening, the live body of a sleeping woman was stretched out between two burning candles, like a sacrificial offering to be savored by the guests (fig. 2.48).[175] A sumptuous feast of roast chicken, prawns, lobster in scallop shells, and exotic fruit was laid out on her prone, nude body, which was replaced by a gold-painted wax mannequin when the exhibition opened to the public. Visitors observed the reclining woman through an iron grille designed by Duchamp,[176] which like the massive wooden door of Étant donnés placed a physical barrier between the spectator and the nude, and intensified the sensation of viewing something obscene or illegal.

Fig. 2.48

Meret Oppenheim (Swiss, born Germany, 1913-1985)

Cannibal Feast, 1959

photographed during the opening of the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surrélisme

---- The sensual, subterranean world of unleashed desires and sexual fantasies that Duchamp and Breton had created was intensified by the sound of heavy breathing, sighs, moans, and other noises associated with lovemaking, punctuated by the recurrent proclamation "je t'aime."[177] The soundtrack, recorded by the Surrealist poet Radovan Ivsic and performed by four female actresses, encouraged the impression that the walls themselves were palpitating, like a living, breathing organism.[178] To add to the intoxicating mood, the air was permeated by the smell of a perfume by Houbigant, appropriately named Flatterie. At the end of one of the maze of tunnels was a dramatic installation of erotic works related to sleep and dream imagery (see fig. 2.49), featuring Alberto Giacometti's Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void) (1935-36), Pierre Molinier's The Flower of Paradise (1955), Robert Rauschenberg's Bed (1955), and on the ceiling Man Ray's Virgin (1955).

Fig. 2.49

Gallery view of the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surrélisme

On the ceiling: Man Ray, Virgin; at rear, left: Giacometti, Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void); center: Rauschenberg, Bed

---- The optical illusion inherent in the faceless Virgin echoes Duchamp's interest in the carnality of vision. The work consists of a seated nude whose thighs take the form of enormous orbs when seen from the front, but when seen from below coalesce to form the open crotch of a female nude that bears down on the viewer due to the distortions invoked by the artist's employment of extreme foreshortening. Hovering overhead near Rauschenberg's Bed — a paint-spattered combine painting consisting of a colorful log-cabin patchwork quilt, a pillow, and part of a sheet[179] — Man Ray's painting may have functioned as a surrogate for Duchamp's splayed nude, then under construction in his New York studio. Visitors first glimpsed Rauschenberg's combine and Man Ray's foreshortened nude from a distance at the entrance to a long, cavernous passageway, anticipating the final placement of Étant donnés in a darkened room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the arrangement of the works by Rauschenberg and Man Ray may in fact have helped Duchamp to determine the exact viewing point for his assemblage.

WE DON'T EAR IT THAT WAY

In the following year, Duchamp designed his final international Surrealist exhibition, entitled Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanter's Domain, which was held at the D'Arcy Galleries at 1091 Madison Avenue in New York from November 28, 1960, to January 14, 1961. Breton gave his old friend and trusted advisor carte blanche to select and install the works for the exhibition, but did not count on Duchamp including Salvador Dalí's recent painting The Sistine Madonna (fig. 2.51). This remarkable trompe l'oeil work placed a detail of Raphael's Sistine Madonna within the convolutions of the human ear. In doing so, the Spanish artist made reference to the Catholic doctrine of the virgin birth of Jesus, thought by theologians in medieval times to have occurred by way of the ear. The painting thus reworks the traditional theme of the insemination of the Virgin Mary by the Word, as it was graphically represented in early Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation in which actual phrases move across the painted surface, from the lips of the archangel Gabriel to the ear of the patient Madonna.

---- This was no ordinary ear, however, since Dalí took it from a photograph of Pope John XXIII that had been reproduced in Paris Match, which he enlarged to the point that the halftone dots introduced by the printing process were unable to carry information about details of form and broke down into a matrix of blobs. He then employed a stencil to transfer the greatly magnified image to canvas before using the moiré technique to superimpose the different layers of imagery. The end result is a visually ambiguous painting whose content and meaning continually shift with the movement of the viewer. Up close, we see an abstract grid; from a little farther away, the image of the Madonna and Child as painted by Raphael can be discerned; and from a distance, we see the great ear, more than two meters high, of the pontiff.

---- Dalí's attempt to imitate the processes of modem industrial printing systems in this 1958 painting was not lost on younger artists such as Andy Warhol , Roy Lichtenstein, Chuck Close, Richard Hamilton, Gerhard Richter, and Sigmar Polke, all of whom would experiment with the effects of blown-up images from newspapers, cartoons, and magazines. But whereas contemporary artists have employed screened Benday-dot patterns and other methods of commercial printing as a commentary on mass-media culture, Dalí's dematerialized Sistine Madonna reflects his effort to reconcile modem art with religion and science under the banner of "Nuclear Mysticism," and as such was considered to be anathema by the Surrealists, who remained virulently opposed to organized religion as well as to nuclear physics. Breton, at his most imperious, persuaded more than twenty members of the Surrealist group to sign a handbill protesting Duchamp's inclusion of Dalí's "portentous Madonna, painted in his most clerical manner and whose large dimensions and recent execution should have excluded it from such a gathering." This leaflet, entitled "We Don't Ear It That Way," included a reproduction of a detail of the Virgin Mary in the Spanish artist's religious painting Assumpta corpuscularia lapislazulina, to which was added a mustache and goatee in homage to Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q. (1919).[180] Although intended to discredit Dalí, whom the tract violently attacked as "Hitler's former apologist, the fascist painter, the religious bigot, and the avowed racist, friend of Franco,"[181] this protest simply gave the artist and his monumental painting some much-needed publicity, and in the process drew the attention of a younger generation of artists to his provocative new work.

---- Duchamp was extremely disappointed by the Surrealist group's bilious protests against Dalí's inclusion in the exhibition. The affair irreparably harmed his friendship with Breton and ensured that Duchamp would never again participate in Surrealist-organized exhibitions. Duchamp was asked by Breton to design and participate in the 1965 Surrealist exhibition en tided L'Ecart absolu (Absolute Deviation) at the Galerie de l'Oeil in Paris. The two men fell out again, however, over the inclusion of a suite of eight large-scale paintings with the provocative tide Live or Let Die, or The Tragic End of Marcel Duchamp in a group exhibition at the Galerie Creuze in Paris in the fall of 1965. Painted by three young Paris-based artists, Gilles Aillaud, Eduardo Arroyo, and Antonio Recalcati, the sequence of collaborative works depicted the interrogation, torture, and murder of Duchamp, whose naked and emasculated corpse is thrown down a flight of stairs in an allusion to the artist's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.

---- The final narrative painting in the series depicted Duchamp's funeral, his coffin draped in an American flag and held aloft by well-known American Pop artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol and their French counterparts, including Martial Raysse and Yves Arman, in a recapitulation of a news photograph of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, Jr.’s burial in November 1963. Although Duchamp was amused by the subject matter of the works, if not their technique (he later told Pierre Cabanne that the series was "horribly painted"[182]), some fifty of his friends, including Breton, Robert Lebel, Jose Pierre, and Arturo Schwarz, signed a statement condemning the series as "a crapulous crime" disguised as a ritual assassination.[183] It was Duchamp's refusal to sign this petition, believing that it merely would give the artists the free publicity they craved, that incurred the wrath of Breton, who once again broke all ties with his friend during the preparations for the 1965 Surrealist exhibition. Whether Duchamp would have designed the exhibition remains an open question, since Étant donnés was close to completion by the end of 1965 and the artist no longer needed to use the format of a Surrealist exhibition to solve problems connected with its construction.[184]

---- In 1960, Duchamp's terse response to Breton's vilification of Dalí spoke volumes about his hurt feelings: "Allow me not to prevaricate in the form of 'explanations and excuses.' Simply that I now regret having agreed to organize this exhibition."[185] Duchamp once explained to the French art critic Alain Jouffroy that "the most Surrealist thing for a Surrealist show in New York would be to show a Social Realist work in the middle of the Surrealist paintings."[186] Tills statement suggests that the artist was fully aware that the provocative gesture of displaying Dalí's monumental, hyperrealist religious painting in a Surrealist exhibition would ruffle feathers and generate publicity for the project. However, Duchamp appears to have been upset that Breton failed to understand the sacrilegious context in which he placed the Sistine Madonna in the exhibition — adjacent to his own work, an action that, as we shall see, hardly can be viewed as supporting the Spanish artist's religious or political views. What the Surrealist leader also had overlooked was Duchamp's completely open and nonsectarian nature, which had enabled him to maintain friendships with both Dalí and Breton over the years, despite their antipathy toward each other.

---- Duchamp had spent a great deal of time with the Spanish artist since 1958, when he began taking an annual, three-month summer vacation in Cadaqués, and had grown to admire the radical independence of his work and ideas. As discussed earlier, in 1959 Dalí assisted Duchamp in producing an edition of prints related to the landscape backdrop of Étant donnés, and would later commemorate their friendship by creating his own tableau-construction in the Dalí Theater-Museum in Figueres, in which visitors peep through one of two holes, placed vertically in the door of an installation containing a trellised arbor with an old metal bedstead, on which sits a large, white plaster object that on closer inspection is revealed to be a giant ear.[187] Dalí's homage to Duchamp's final tableau-construction also denotes gratitude to his friend for defending The Sistine Madonna against the charge leveled by the Surrealists that this painting of a blown-up ear containing a painting by Raphael should not have been included in the 1960 exhibition.

---- For too long, this controversy has overshadowed Duchamp's own efforts to breathe new life into the Surrealist movement. In the 1960 exhibition, he again situated the works of art on display within a stimulating and enigmatic environment, which featured a length of garden hose that wound its way through the galleries like an uncoiled snake; a toy electric train that circled one of the gallery's bay windows while pulling a string of cars labeled with the names of the exhibiting artists; jarring music broadcast from concealed speakers that later was revealed to be a recording of a child's mistake-filled piano practice (performed by Topher Delaney, the daughter of Denise Browne Hare); an antique timepiece at the entrance, where guests at the opening had their invitations punched; and electric clocks hanging from the ceiling of the four exhibition galleries, each one telling a different time, which Duchamp later joked were intended to "symbolize the omnipresence of time."[188]

Fig. 2.50

Marcel Duchamp

Coin Sale, with Salvador Dalí's The Sistine Madonna, at the exhibition Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanter's Domain, D'Arcy Galleries, New York, 1960-61

---- Among the 150 works of art on display was Duchamp's own installation of a cage housing three live white chickens illuminated by a green light, entitled Coin Sale (see fig. 2.50). The title was spelled out by Duchamp in an arrangement of nickels, but its double meaning in French soon became apparent to the visitors after the overfed chickens turned this side of the gallery into a foul-smelling "dirty corner." The subversive placement of this installation beside Dalí's Sistine Madonna relates it to the ongoing Étant donnés project, in which Duchamp similarly planned to introduce an unsettling work in a far-flung corner of the prestigious Philadelphia Museum of Art, where some patrons and visitors no doubt would find the work distasteful and perhaps even "dirty." The artist also included in the 1960 Surrealist exhibition his 1914 readymade Pharmacie, which bears a clear thematic relationship to the landscape backdrop of Étant donnés, as well as his Wedge of Chastity (FIG. 2a.42), whose tide and subject matter strongly resonate with his deeply blasphemous juxtaposition of Dalí's chaste Madonna and a cage of live chickens.

Fig. 2.51

Salvador Dalí

The Sistine Madonna, 1958

Oil on canvas, 225,7 × 191,1 cm (887⁄8 × 751⁄4 inches)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Drue Heinz, in memory of Henry J. Heinz II, 1987

---- In the Coin Sale installation, Duchamp effectively used The Sistine Madonna as a stand-in for the reclining nude in Étant donnés, in much the same way as Man Ray's Virgin implicitly represented the figure in the 1959 Surrealist exhibition. In this regard, it is perhaps worth noting the artist's request that a 1966 Man Ray watercolor entitled Hommage à Marcel Duchamp, on the same explicitly sexual theme as Virgin, appeared on the cover of the special Duchamp issue of the London-based magazine Art and Artists (fig. 2.52), published in July 1966 to coincide with the Tate Gallery retrospective exhibition The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp.[189] That Duchamp would allow another artist's work to grace the cover of a publication devoted to his own life and art suggests that Man Ray's Virgin held special significance for him. It is surely no coincidence that Man Ray made his third and final version of the work in 1969 (fig. 2.53), after learning through the international press of his late friend's startling mise-en-scène of illicit looking, which had just gone on view in Philadelphia.

Fig. 2.52

Man Ray

Hommage à Marcel Duchamp, 1966

reproduced on the cover of Art and Artists, July 1966

Fig. 2.53

Man Ray

Virgin, 1969

Oil on canvas, 33 × 24 cm (13 × 97⁄16 inches)

Fondazione Guglielmo Marconi, Bologna

---- Duchamp's request that Man Ray design the 1966 magazine cover speaks not only to their lifelong friendship and shared interest in eroticism, but also to Man Ray's intentional reference to Duchamp's earlier abstract works, such as Virgin, No. 1 (1912), in his spread-eagled Virgin of 1955. Taking to its logical conclusion the challenge to fixed notions of authorship raised by the Art and Artists cover — as well as their earlier collaboration in the construction of Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp's lascivious alter ego — at the opening of the 1966 retrospective Man Ray confused and confounded the assembled guests by introducing himself as the guest of honor. "Yes, I am Marcel Duchamp," he declared to a writer for the London Observer. "Let me say that I'm pleased with my retrospective show at the Tate. I think the organization is wonderful. It's come at the right moment in my life. I was born in 1860, which makes me 106 right now. You know, I must introduce you to my friend. Marcel Duchamp!"[190]

Fig. 2.54

Marcel Duchamp

Moulin à café (Coffee Mill), 1911

Oil and pencil on board, 33 × 12,7 cm (13 × 5 inches)

Tate Collection, London. Purchased 1981

---- The peephole located on the back cover of the Tate Gallery's catalogue for the Duchamp retrospective also can be understood as a reference to the viewing mechanism of Étant donnés, even though the artist maintained, to the very end, a code of absolute silence surrounding its existence. This secrecy was jeopardized, however, by the inclusion in the exhibition of an important early study for Étant donnés, which Maria Martins had lent after receiving a request from Richard Hamilton, the exhibition's organizer, for any works by Duchamp in her collection, since he was aiming for as complete a retrospective as possible. Martins not only lent her Coffee Mill painting (1911; fig. 2.54), but also the small-scale leather-over-plaster study of the mannequin's torso in Étant donnés, which Duchamp had dedicated to her with the following inscription: "This lady belongs to Maria Martins, with all my affections, Marcel Duchamp 1948-49" (FIG. 2a.14). In a recent interview, Hamilton recounted the artist's shocked reaction when he saw the work installed at the 'Fate Gallery. Visibly upset, Duchamp demanded to know where Hamilton had found the work, but when he was satisfied that it had come from Martins, he remarked that it was "a pity" and declined to answer any further question about its materials or meaning.[191]

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 ---- Part 5

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 100-107, 124-126. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[158] Alyce Mahon erroneously credits Boîte alerte exclusively to Mimi Parent, thus denying any involvement by Duchamp in the work; see Mahon, Surrealism and the Politics of Eros, p. 166. However, as we have seen in Enrico Donati's collaboration with the artist on the Prière de toucher cover of the 1947 Surrealist exhibition catalogue, Duchamp was more than happy to let other people have some creative input in his projects, but only after he had come up with the initial idea. In the case of the Boîte alerte it seems inconceivable that Duchamp did not come up with the suggestion of a green mailbox to contain the exhibition catalogue and the lascivious contributions of his Surrealist colleagues. The idea resonates strongly with other works in his oeuvre, such as The Green Box (1934), which was designed to house the meticulously reproduced facsimiles of his notes for The Large Glass in a green-flocked cardboard box. Like Donati before her, Parent may have designed and executed the Boîte alerte, but the work would not have existed without Duchamp's original idea.

[159] Duchamp, Salt Seller, p. 106. This pun was first published in Littérature, n.s., no. 5 (October 1, 1922).

[160] In a 1966 interview, Duchamp continued the argument he first posited in his April 1957 "Creative Act" lecture in Houston (see Marcel Duchamp, "The Creative Act," Art News [New York], vol. 56, no. 4 [Summer 1957], p. 29): "The artist's accomplishment is never the same as the viewer's interpretation .... A work of art is dependent on the explosion made by the onlooker"; Dore Ashton, "An Interview with Marcel Duchamp," Studio lnternational, vol. 171, no. 878 (June 1966), repr. in Anthony Hill, ed., Duchamp, Passim: A Marcel Duchamp Anthology (London: Gordon and Breach Arts International, 1994), p. 73. Duchamp had been interested in the spectator's role in the creative act since the 1910s, as seen, for example, in the title of his 1918 glass construction, To Be Looked. at [from the Other Side of the Glass] with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour, which not only suggests the onlooker's active participation, but also specifics how he or she should view the work; see Anne Umland and Adrian Sudhalter, eds., Dada in the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2008), p. 124.

[161] André Breton, "Avis aux exposants/aux visiteurs," Exposition internationale du Surréalisme, 1959-1960, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Daniel Cordier, 1959), trans. and repr. in Breton, Surrealism and Painting, pp. 378-79.

[162] Ibid., p. 378.

[163] Ibid., p. 377.

[164] Ibid., p. 382. Unknown to Breton, the author of Emmanuelle was not the Thai-born French actress Marayat Rollet-Andriane, as was widely believed at the time. but rather her husband, Louis-Jacques Rollet-Andriane. When the book was first published in 1959, it caused a sensation and was immediately banned by de Gaulle's government. Breton's allusion to the scandalous novel details the sexual exploits of the bored housewife of a diplomat who is unable to satisfy her, due to an accident that rendered him impotent, and the novel probably was intended to highlight contemporary debates in France surrounding eroticism and pornography.

[165] See Breton, "Avis aux exposants/aux visiteurs," p. 379.

[166] Ibid., p. 383.

[167] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in "Marcel Duchamp Speaks," interview with Charles Mitchell and Richard Hamilton, taped September 1959, broadcast BBC Radio, Art, Anti-Art, November 13, 1959, and August 12, 1960; transcription repr. in Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (1997), vol. 1, p. 214-15.

[168] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 88.

[169] The spectacular installation design of the Exposition inteRnatiOnal du Surréalisme is discussed at length in Marie Bonnet, "Anti-Reality! Marcel Duchamp, André Breton et la VIIIe Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme, Paris, galerie Daniel Cordier, 1959," Les Cahiers du Musée national d'art moderne, no. 87 (Spring 2004), pp. 97- 115. Cécile Bargues also has discussed the installation in relation to Duchamp's Étant donnés project; see Bargues, Passing through E.R.O.S.: Marcel Duchamp and the 8th Exposition lnteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme," in Marc Decimo, ed., Marcel Duchamp and Eroticism (Newcastle, UK; Cambridge Scholars, 2007), pp. 239-54.

[170] Daniel Spoerri, quoted in Susan Hapgood, "Daniel Spoerri: Interview" (Paris, April 26, 1992), in Hapgood, ed., Neo-Dada: Redefining Art, 1958-62, exh. cat. (New York: American Federation of Arts and Universe, 1994), p. 134. This installation had its origins in the imagined cave houses that Tristan Tzara described in Minotaure, in which he refers to the interior of the house as a kind of womb or prosthetic umbilical space.

[171] In conversation with his close friend the Polish art critic Constantin Jelenski, Bellmer declared that "the origin of my scandalous work" lay in the fact that "the world for me is a scandal"; quoted in Jelenski, "Hans Bellmer, or the Displaced Pain," Arts Magazine (New York), vol. 38, no. 6 (March 1964), p. 50.

[172] Mahon, Surrealism and the Politics of Eros, p. 159.

[173] Robert Benayoun, Érotique du surréalisme (Paris: Pauvert, 1965), p. 231.

[174] Ibid.

[175] Oppenheim's moveable feast was first staged as a banquet, or festin, for friends at the Kunsthalle, Berne, in the spring of 1959, when the artist and four friends ate food off the nude body of a woman who had been put to sleep with a light sedative. When news of this intimate Spring Banquet reached Breton, he asked Oppenheim to reenact it in December for the inauguration of the E.R.O.S. exhibition. Oppenheim later expressed her disappointment with the Parisian festin, over which she had little control, believing that its brutalized vision of Eros was destructive and tragic for the "second sex"; see Peter Gorsen, "Meret Oppenheim's Banquet — A Theory of Androgyne Creativity," in Meret Oppenheim: A Different Retrospective, exh. cat. (Zurich: Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Arnhem, and Stemmle, 1997), pp. 35-37.

[176] See Annette Michelson, "But Eros Sulks," Arts Magazine (New York), vol. 34, no. 6 (March 1960), p. 35. Along with the grille, Duchamp had originally planned to create a landscape environment in this final section of the 1959 Surrealist exhibition similar to that found in Étant donnés, as seen in his unrealized instructions to Breton: "We need a grille and stagnant water at the back, a little moss"; see André Breton, "Suggestions from Marcel (September 9, 1959)," handwritten notes on the back of E.R.O.S. exhibition stationery taken during a conversation with Duchamp, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, repr, in Marie Bonnet, "Anti-Reality!" p. 110. In the same conversation with Breton, Duchamp suggested that the entrance resemble "a rubber vagina poorly made but suggestive," another unrealized idea that was replaced in the final installation with the pearl curtain in an ogival door; ibid., p. 101.

[177] See Radovan Ivsic, "When the Walls Sighed in Paris," trans. Roger Cardinal, in Jennifer Mundy and Dawn Ades, eds., Surrealism: Desire Unbound, exh. cat. (London: Tate, 2001), p. 287.

[178] Ibid.

[179] According to James Leggio, the first art critics to review Rauschenberg's Bed — with its splattered paint and slashed pencil lines — saw it as evidence of a horrible crime, possibly the scene of a sex murder after the corpse had been removed. This overly literal reading of the work led to the piece being censored from an exhibition in Spoleto, Italy, in 1958, when officials removed it from public view and hung it in an office. The scandalous reception of the paint-spattered work, with its perceived associations with blood and sperm, may have persuaded Duchamp to include it in the 1959 E.R.O.S. exhibition. See Leggio, "Robert Rauschenberg's Bed and the Symbolism of the Body," in Leggio and Helen M. Franc. eds., Essays on Assemblage (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1992), p. 80.

[180] This leaflet was published by the Surrealist group in Paris and signed by twenty-five members, to protest Duchamp's inclusion of Dalí's work in the international Surrealist exhibition held at the D'Arcy Galleries in New York in 1960.

[181] "We Don't Ear It That Way" (Paris, 1960).

[182] Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p.103.

[183] For an excellent account of the controversy surrounding the series of paintings known collectively as Live or Let Die, or The Tragic End of Marcel Duchamp, see Jill Carrick, "The Assassination of Marcel Duchamp: Collectivism and Contestation in 1960s France," Oxford Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 1 (2008), pp. 1-25.

[184] Ibid.

[185] Marcel Duchamp, letter to André Breton, December 11, 1960, quoted in Affectionately, Marcel, p. 372.

[186] Alain Jouffroy, "Hearing John Cage, Hearing Duchamp," trans. Monique Fong, Étant donné Marcel Duchamp, no. 6 (2005), p. 130.

[187] See Charles Stuckey, "Dalí in Duchamp-Land," Art in America, vol. 93, no. 5 (May 2005), p. 155; I am grateful to Charlie Stuckey for his identification of the plaster object as a giant ear.

[188] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in John Canaday, "Art: Surrealism with the Trimmings," New York Times, November 28, 1960, p. 36.

[189] Man Ray's cover design was listed on the tide page of the magazine as "Hommage à Marcel Duchamp — Man Ray, 1966"; Art and Artists, vol. 1, no. 4 (July 1966). Designed to coincide with the largest retrospective exhibition of Duchamp's work to be held in Europe in his lifetime, the magazine paid tribute to "the life-work of one of the most important artist-philosophers of our time"; ibid., p. 4.

[190] Man Ray, quoted in "Growing Up Absurd; London Observer, June 19, 1966, Weekend Review, p. 23. According to the English painter Howard Hodgkin, who gave Man Ray a lift back to his hotel after the Duchamp exhibition opening at the Tate Gallery, the American artist maintained this charade to the very end , much to the amusement of his Arts Council hosts; Hodgkin, interview with the author, Philadelphia, March 22, 2001.

[191] Richard Hamilton, interview with the author, Northend, Oxfordshire, UK, May 27, 2008.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES