Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Michael R. Taylor

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 2

CONSTRUCTION (Part 3)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 88-99, 123-124. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Part 1 Part 2 ---- Part 4 Part 5

GALLERY 1759

On December 27, 1950, Duchamp's patrons Louise and Walter Arensberg signed a deed of gift donating their famed modern and pre-Columbian collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Duchamp had agreed to hang the works in the Museum's newly completed modern art wing several years before the contract was signed, believing that there was "a good air of permanency in the building and in the offer."[124] As the installation plans developed over the next three years; he must have determined that the final resting place for Étant donnés would be located somewhere within the suite of galleries that would soon contain the largest collection of his work, including The Large Glass, which Katherine Dreier donated to the Museum in November 1952 at Duchamp's request. By 1953, the year Duchamp made Moonlight on the Bay of Basswood, the installation plans for the Arensberg Collection had reached an advanced stage, requiring numerous visits by the artist to meet with Fiske Kimball, the Museum's Director from 1925 until 1955, to review the proposed arrangement of the galleries and to choose the exact placement of The Large Glass. It may have been at this time that Duchamp selected Gallery 1759 as the future site for Étant donnés, since the landscape backdrop for the work clearly was on his mind during his vacation with the Hubacheks in August of that year. That Duchamp knew the dimensions of the room by this time is confirmed by a drawing he made in 1951, although this sketch proposes that the Museum install works from the A. E. Gallatin Collection in Gallery 1759 and display his own work elsewhere in the galleries (fig. 2.28).

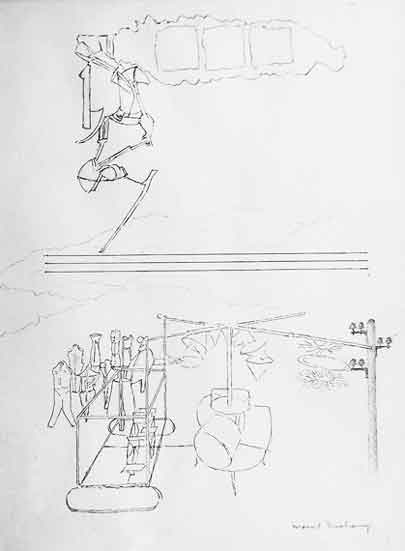

Fig. 2.28

Marcel Duchamp's proposed floor plan for the modern art wing

at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, September 7, 1950

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Arensberg Archives

---- Along with the important occasion of his second marriage, 1954 was also the year that Duchamp installed the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in galleries that had been specially designated for modern art (fig. 2.29). The artist supervised the permanent installation of The Large Glass on July 19, 1954, when it was cemented to the floor and held in place by two aluminum columns in a large gallery overlooking the Museum's East Terrace.[125] It was most likely at this time that he chose the small, adjoining room, known then as Gallery 1759 in which he had displayed paintings by Wassily Kandinsky and Alexey von Jawlensky as the final resting place for Étant donnés. Duchamp must have been aware that the installation of his final masterwork would displace what he later called the "retinal" paintings and works on paper by Kandinsky and Jawlensky (fig. 2.30), and in fact these two Russian-born artists have never since been allocated a permanent gallery; instead their artwork haunts the modern art wing like Banquo's ghost, returning every now and then for a short time to replace paintings on loan, only to be removed to storage when the works return.

Fig. 2.29

Duchamp installing The Large Glass at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954

Fig. 2.30

Gallery 1759, with works by Wassily Kandinsky and Alexey von Jawlensky,

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954

---- For The Large Glass, Duchamp deliberately chose a gallery directly overlooking Maria Martins's standing nude sculpture Yara (see fig. 1.9). which had graced the East Terrace fountain since 1942. Duchamp's instructions called for a door to be made, leading from this gallery to a balcony overlooking the East Terrace and the city beyond.[126] When the door was open, visitors in the gallery would see the gushing fountain through the glass panes of his seminal early work and, at the same time, view Martins's bronze sculpture below.[127] The arrangement would take on extended significance when Étant donnés was unveiled to the public, since Yara, a work almost certainly based on Martins's own body, would be placed in dialogue with the interior scene of Duchamp's tableau-construction, which also featured a nude torso based on that of his former lover.

---- Eva H. Turner, Director of the Museum when the artist's tableau-construction first went on display, recalled that "Duchamp chose this gallery in the early 1950s, so he knew exactly where Étant donnés was going — he had all the measurements he needed to make the work fit perfectly."[128] With its proximity to The Large Glass, Gallery 1759 — a long, narrow space running along the outer edge of the modern art wing was the ideal location for his startling mise-en-scène. The dark, corridor-like room also fulfilled the artist's desire to place the spectator in the position of voyeur when looking through the installation's peepholes, combining the thrill of seeing a nude woman with splayed legs and the fear of being caught looking at such a "forbidden" subject. Gallery 1759 was twenty-nine feet, six inches long and eleven feet, seven inches wide, with a ceiling height of nine feet, two inches. The space would be cut approximately in half by the installation of Étant donnés, which Duchamp constructed within the parameters of the room's dimensions.' Around 1954, the artist pasted a diagram indicating the height, width, and length of the gallery to a piece of cardboard that had been used as a cutting board but now contained various notes and messurements related to the installation of his work in the "Phila room" (see fig. 2.31).

Fig. 2.31

Duchamp's floor plan for Gallery 1759 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, c. 1954

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d'Harnoncourt Records

---- With these dimensions at hand, the artist knew generally how wide to make the brightly illuminated trompe l'oeil backdrop with its undulating hills, waterfall and mist-covered lake,[129] which has been shown to be a hand-colored collotype collage based on the photographs that Duchamp took in Switzerland in August 1946 during his vacation with Mary Reynolds. To create the final backdrop, Duchamp first made the working study mounted on plywood (FIG. 2a.2), with a hinge mechanism that allowed it to be folded for easy transportation while also hiding the image from view. For this preliminary study, Duchamp used cut-and-pasted enlargements of the original photographs of the waterfall to create a hand-colored wooded landscape. The landscape study eliminated all traces of the huilerie building, the church spire at Chexbres, and the overgrown shingled rooftop of a pistol-shooting range in the foreground that is visible in several of the Bellevue images, including FIG. 2a.9, at the bottom center.

---- The artist endowed his study for the landscape backdrop of Étant donnés with a palpable, sfumato-like atmosphere akin to that found in the backgrounds of the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci, although the rustic colors and radiant opticality of Duchamp's wooded hills seem closer to the palette and techniques of French Impressionism, with which he had experimented in his youth. The warm colors or the shrubbery and trees, as well as the rocks found in both the preliminary study for the landscape backdrop and the final version, relate to previously unpublished notes that Duchamp made on both sides of a piece or paper at the Bellevue gorge in 1946, in which he recorded the greenish yellow and ash-green colors of the trees, the sandy, golden-colored rocks with their bases in the water, and even the spot of shit on the boulders near the oil distillery (fig. 2.32a,b).

Fig.2.32

Duchamp's double-sided note

recording the colors of the Bellevue waterfall and landscape, 1946

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d'Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.40

Marcel Duchamp

Landscape (study for Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage), 1959

Collotype in black ink on cellulose acetate "silk" fabric backed with paper

74 × 102,8 cm (291⁄8 × 407⁄16 inches)

Private collection

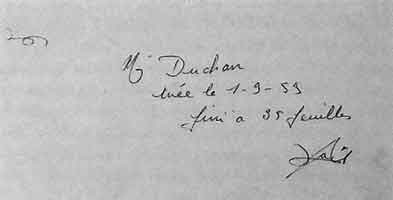

---- In the summer of 1959, Duchamp reproduced this intermediate backdrop as a series of thirty-five prints, two examples of which have survived (FIG. 2a.40 and FIG. 2a.41). One print, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was determined to be a collotype printed on fabric. An inscription on the verso of one of these prints — "M Duchan [sic] / tirée le 1-9-59 / fini a 35 feuilles / Dalí" (fig. 2.33) — implies that Duchamp made these prints with the assistance of Salvador Dalí during his annual vacation in Cadaqués, a small town in Catalunya, in northeastern Spain. Duchamp spent a great deal of time with Dalí at his studio in the small fishing village of Port Lligat, located less than a kilometer from Duchamp's summer residence. Dalí had a great deal of experience in printmaking and was thus the perfect person to advise and help his friend with this print edition. Given the size of the collotype machine needed for this project, the two artists may have used a commercial printing facility nearby, either in Barcelona or the surrounding region, or even in Paris at the collotype studios of Vigier et Brunissen or Duval — studios Duchamp had employed for The Green Box (1934) and the Boîte-en-valise (1935-40).[130]

FIG. 2a.41

Marcel Duchamp

Landscape (study for Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage), 1959

Collotype in black ink with green oil paint on cellulose acetate "silk" fabric backed with paper

63,2 × 88,9 cm (247⁄8 × 35 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mme Marcel Duchamp

Fig. 2.33

Verso of Duchamp's Landscape (study for Étant donnés), 1959, detail (FIG. 2a.40)

Ink on paper

Private collection

---- Teeny Duchamp later recalled that the artist once took the landscape to Cadaques.[131] It is likely that Duchamp finished the collage in Spain in 1959 and transported it back to New York in its current, unfolded state. Richard Hamilton remembered seeing a colored landscape on an easel in Duchamp's summer home that year, but had no idea at the time that the fragmented, irregularly shaped work related to a larger project.[132] I believe that Duchamp brought the landscape collage on plywood with him to Cadaqués to work with Dalí on an edition of collotype prints based on its composition. Dalí's invaluable inscription supplies us with the following information: the collaborative nature of the effort, since he lists both artists' names; the size of the edition (thirty-five); the date they were pulled (on or before September 1, 1959); and by extension the location where the prints were made the Costa Brava, since both artists were living and working there on that date.

---- The landscape print on fabric owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art shows a small amount of green paint on the trees and landscape on the left-hand side (FIG. 2a.41). The presence of green pigment on this collotype suggests that the artist experimented with paint color before beginning work on the full-scale landscape backdrop for Étant donnés. Scientific analysis undertaken at the Museum showed that the backdrop consists of cut-and-pasted fragments of collotypes on paper. These fragments may relate to the 1959 collotype edition, or may have been cut from subsequent prints that used the same plates. However, since only two of thirty-five prints from the 1959 edition have survived, both on fabric, we may never know whether the remaining thirty-three were printed on paper or fabric. As we shall see, the collotype print edition relates to a failed publication project Duchamp had planned with Robert Lebel, the subject of which clearly related to Étant donnés.

---- At some point after Duchamp made the landscape on plywood, he completed the final landscape backdrop, utilizing superimposed pieces of collotype prints that were repeated to fill the entire composition. Once Duchamp was pleased with the vista, he painted several areas with green and reddish brown, adding blazing autumnal colors to the dense cluster of trees and shrubs in the hilly landscape, presumably after consulting with the color notations he had made in Switzerland in 1946. The particular pigments and media that the artist used to achieve these colors are discussed by Price and Sutherland et al.[132-a] The wooden structure containing the final landscape stands nearly upright, at a slight angle to the viewer, and is supported by two legs and two wooden struts nailed to the floor. When finished, the backdrop was attached to a ground-glass support above the skyline and to a plywood support below. Behind the glass, in the upper section of the landscape, an enclosed box is illuminated by a forty-watt fluorescent lightbulb and contains pieces of white absorbent cotton, partly stained with dark blue ink, that form the fluffy clouds visible in the sky. Covering the back of the box was a sheet of blue paper tinted with spray paint that gave the sky its hazy luminescence, and that recalled the distinctive hue of the blotting paper used in Moonlight on the Bay at Basswood.

---- Duchamp worked on the backdrop for Étant donnés at least throughout the 1950s, while also surreptitiously collecting materials for the environment in which he placed the nude. The bed on which the mannequin reclines is composed of twigs and fallen leaves that were lovingly selected by Duchamp and his new bride, Teeny, on expeditions to Central Park, the Hudson River Palisades, and the New Jersey countryside,[133] especially the grounds of their summer home in Tewksbury Township in Hunterdon County, where they had honeymooned following their marriage on January 16, 1954.[134] Duchamp originally planned that the nude figure would lie only on a pile of dry leaves, but that idea proved impractical when the artist discovered her weight needed additional support, and so he added a mixture of dead leaves and heavier twigs fastened to wire mesh.[135] The couple, along with Teeny's three children from her first marriage, vacationed in Tewksbury for the next two summers, before selling the house at 22 Burrell Road and its sixty-three acres of mushroom-filled woods in 1956.

WITH MY TONGUE IN MY CHEEK

The timing of Duchamp's installation of the Arensberg Collection in 1954 denotes the dramatic shift from abstract concept to physical realization of the mannequin's pastoral environment in the tableau-construction, a process that coincided with the artist's second marriage. Duchamp marked the happy occasion by giving his new wife a wedding present that relates specifically to Étant donnés, namely, Wedge of Chastity (1954; FIG. 2a.42). Art historian Peter Read has observed that "the title Chastity Wedge, echoing 'chastity belt,' would be a better English equivalent of the French coin de chasteté, which echoes and resembles ceinture de chasteté."[136] This erotic sculpture consists of a hard wedge of galvanized plaster, painted brown and firmly gripped by a gummy, fleshy cleft of pink dental plastic, perhaps giving material form to the artist's later statement, in 1956, that he "would like to grasp an idea as the vagina grasps the penis."[137] Underscoring the complex psychosexual undercurrents of this unusual wedding gift, the glistening pink material, used by dentists to fill gums, also suggests that Duchamp may have intended the work as a variation on the age-old vagina dentata motif, which fascinated the Surrealists. The unconventional wedding present also appears to acknowledge Teeny's initiation into the secret world of Étant donnés as the plaster section likely derived from the mold of the mannequin that was cast by Ettore Salvatore. Indeed, during much of its construction, she was Duchamp's sole confidant and co-conspirator.

FIG. 2a.42

Marcel Duchamp

Coin de chasteté (Wedge of Chastity), 1954

Sculpture in two sections, copper-electroplated plaster and dental plastic

5,6 × 8,6 × 4,2 cm (23⁄16 × 33⁄8 × 15⁄8 inches)

Private collection

Fig. 2.34

Richard Lusby (1919-2001)

Marcel Duchamp with a copy of the deluxe edition

of Robert Lebel's monograph Sur Marcel Duchamp, featuring

the "Eau & gaz à tous les étages" plaque (FIG. 2a.45), 1959

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers.

Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

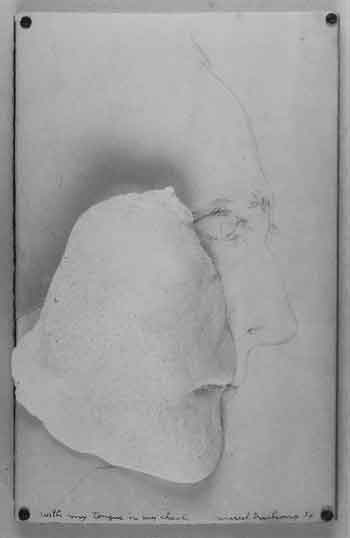

FIG. 2a.43

Marcel Duchamp

With My Tongue in My Cheek, 1959

Plaster and pencil on paper, mounted on wood

25 × 14,9 × 5,1 cm (913⁄16 × 57⁄8 × 2 inches)

Musee National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

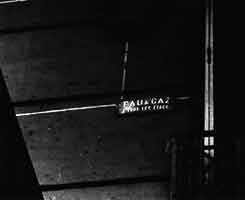

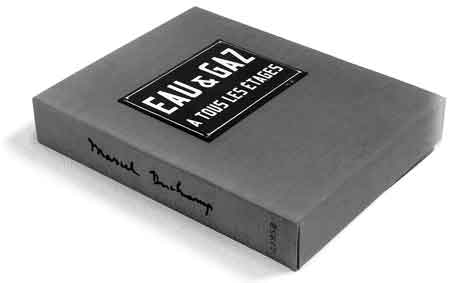

---- By 1959, Ducharnp had completed the mannequin and her bier of twigs and branches, and had made significant progress on the design of the landscape backdrop. We know that by September 1, 1959, he had completed the collage landscape on plywood and had made an edition of thirty-five collotypes based on its composition. These black-and-white collotypes, if printed on paper, may have supplied the artist with the fragments that he collaged together and embellished with color to create the final landscape backdrop, which he then painted with oil paint and crayon to obtain the vibrant colors of the Bellevue waterfall and its lush surroundings. During the same summer vacation in which he collaborated with Dalí on the collotype landscape edition, the artist constructed an elaborate multimedia triptych comprised of three relief sculptures, entitled With My Tongue in My Cheek (FIG. 2a.43), Torture-morte (FIG. 2a.44), and Sculpture-morte (see fig. 2.42). The individual works had been made for a publication project that Duchamp was planning with Robert Lebel, a close friend who recently had issued the first comprehensive monograph on the artist, Sur Marcel Duchamp, published in 1959 by Trianon Press in Paris in standard and deluxe editions. The box cover of the deluxe edition of the book, limited to 137 copies, bore a diminutive plaque with the phrase "Eau & gaz à tous les étages" (Water & gas on every floor) in white letters on a blue background (FIG. 2a.45 and fig. 2.34), based on the plaques that still adorn many buildings in Paris (fig. 2.35). The sly reference to the waterfall and illuminating gas of Étant donnés can be understood as yet another attempt by Duchamp to allude to his secret project, knowing that the full ramifications of this gesture would not be understood until after the work was publicly unveiled.

FIG. 2a.44

Marcel Duchamp

Torture-morte, 1959

Painted plaster, synthetic flies, and paper mounted on wood, with glass

29.5 × 13.4 × 5.6 cm (115⁄8 × 55⁄16 × 43⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 2.35

Anonymous undated photograph of an apartment building in Paris,

with an "Eau & gaz" plaque, c. 1959

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers.

Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

FIG. 2a.45

Marcel Duchamp

Eau & gaz à tous les étages (Water and Gas on All Floors), 1959

Cover of deluxe edition of Robert Lebel's Sur Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Trianon)

Linen-covered cardboard box with collotype-printed and stencil-colored plaque

34.9 × 26.7 × 5.4 cm (133⁄4 × 101⁄2 × 21⁄8 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Henri Marceau

---- Lebel's 1959 monograph on the artist had so pleased Trianon Press owner Arnold Fawcus, who founded the publishing company in 1947, that in the summer of 1959 he commissioned Duchamp and Lebel to begin work on a second book project that was to have afforded both artist and writer a great deal of freedom. Unfortunately, the book was abruptly canceled later that year. Although the circumstances surrounding the cancellation remain shrouded in mystery,[138] it is clear that Fawcus objected to the subject matter of the works that Duchamp made for inclusion in the book, all of which can be related to his ongoing Étant donnés project. According to Lebel's account,

In 1959 a Paris publishing house commissioned Duchamp and me to prepare a book that we were free to write and illustrate independently, without consulting one another. When Duchamp, then in Cadaqués, responded immediately, sending three hermetically sealed boxes containing, as illustrations, With My Tongue in My Cheek, Torture-morte, and Sculpture-morte, the commission was canceled without further ado.... The sculptures, which the publisher retained as a bad joke, were in line with Female Fig Leaf, 1950, Objet-dard, 1951, and Wedge of Chastity, 1954, all of which belong to the series of special experiments with relief that Duchamp made for Étant donnés ... the work he had been secretly preparing since 1946; in it, bringing sexual cynicism to the limits, he sardonically celebrated the nuptials of eroticism and death.[139]

When seen together, With My Tongue in My Cheek, Torture-morte, and Sculpture-morte form a self-portrait triptych that speaks to the artist's renewed engagement with body casting in Cadaqués in the summer of 1959. That Duchamp intended to reproduce the three sculptural works in the proposed publication for Trianon, along with the collotype print of the Étant donnés landscape that he also sent to Fawcus from Cadaqués, suggests that the book's subject matter related to the tableau-construction, as does an inscription on the fifth and final work that the artist sent to Paris that year: "COLS ALITÉS / Projet pour le modelè 1959 de 'La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même'" (COLS AUTÉS / Project for the 1959 model of "The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even"). Cols alités (FIG. 2a.46) is one of two delicate landscape drawings that the artist completed in 1959, thus underscoring the singular importance of that year for the Étant donnés project. Indeed, the increased level of the artist's activities led to speculation in the press that "Duchamp was sequestered in a studio somewhere doing something," although the immense secrecy surrounding his work ensured that this rumor remained unconfirmed.[140]

FIG. 2a.46

Marcel Duchamp

Cols alités (Bedridden Mountains), 1959

Ink and pencil on paper

32,1 × 24,4 cm (125⁄8 × 95⁄8 inches)

Private collection

---- Cols alités updates the agricultural and technological themes of The Large Glass by depicting through its transparent panes a distant range of hills (collines) and at lower right an electricity pole with power lines.[141] The nonsensical French title can be translated as "necks confined to bed," "bedridden clefts," or "bedridden mountains" (in the sense of a mountain pass, like the Khyber Pass).[142] The title also can be read phonetically as a pun on causalité, thus raising the important question of the cause-and-effect relationship between The Large Glass and Étant donnés. Duchamp's important inscription on the verso of this drawing suggests that Étant donnés, as it appeared in 1959, could be understood as an updated, three-dimensional version or model of The Large Glass. A significant point midway between the two works can be found in the section of the 1942 First Papers of Surrealism catalogue entided "De la Survivance de certains myths et de quelques autres mythes en croissance ou en formation" (On the Survival of Certain Myths and on Some Other Myths in Growth or Formation) (fig. 2.36). Under the heading "La Science triomphante" (Science Triumphant), we see the origin of the electricity pole of Cols alités in Puvis de Chavannes's allegorical mural The Physics (1895-96; fig. 2.37), which was reproduced alongside an Alfred Jarry quotation and a photograph of a suspended bat with outspread wings, all of which allude to the iconography of The Large Glass. Duchamp's notes and diagrams for this earlier work are filled with references to the electrical stripping of the Bride and the apotheosis of her virginity, concepts that the artist returned to and updated through the erotic topology of the landscape and the body in Étant donnés.

Fig. 2.36

"La Science triomphante" (Science Triumphant),

from the exhibition catalogue for the First Papers of Surrealism, 1942

Fig. 2.37

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (French, 1824-1898)

The Physics, 1895-96

Oil on canvas, 434,9 × 218,4 cm (172 × 86 inches)

Boston Public Library

---- The lone telegraph pole in Cols alités, with a hilly landscape in the far distance, appears again in Du Tignet (FIG. 2a.47), a lovingly rendered pencil drawing that Duchamp made as a present for his friend Maurice Fogt. While the telegraph pole with its wires and insulators is almost identical to the one found in Cols alités, the single range of undulating hills on the horizon is drawn in far greater detail in Du Tignet than is the faint, swifdy sketched impression of a landscape behind The Large Glass that appears in the variant drawing. The rolling, voluptuous hills in Du Tignet were almost certainly inspired by the view from Fogt's house at Le Tignet, near the city of Grasse in southeastern France, where Duchamp and Teeny spent a three-week vacation in August 1959, whereas the telegraph pole was based on one of the pylons standing to the west of the Fogt property. This information confirms that the artist made Du Tignet, which he enclosed with a letter to Fogt on August 9, 1959,[143] before completing the related Cols alités drawing, a work that further elaborates on the connection between the desiring Bride and her erotic landscape environment, powered in this work by the electricity transmitted from the telegraph pole.

Fig. 2a.47

Marcel Duchamp

Du Tignet (From Tignet), 1959

Pencil on paper

30,5 × 23,5 cm (12 × 91⁄4 inches)

Collection of Robert Shapazian, Los Angeles

---- When Arnold Fawcus canceled the proposed book project related to Étant donnés, Robert Lebel purchased Cols alités, along with the three relief sculptures — With My Tongue in My Cheek, Torture-morte, and Sculpture-morte — that make up Duchamp's self-portrait triptych , while the collotype print remained in Fawcus's possession at the Trianon Press. With My Tongue in My Cheek is a three-dimensional embodiment of tongue-in-cheek humor denoting insincerity, irony, or whimsical exaggeration. Duchamp's title perhaps refers to his own irreverent approach to "serious" art-making, although the work should not be discounted as a clever one-Liner, since the use of cast plaster, as Lebel noted, provides a direct connection with Étant donnés. Duchamp had Teeny cast his own cheek and jaw in plaster, even going so far as to insert a walnut in his cheek to create the bulgelike protuberance that stands for the unseen tongue of the title. He then mounted the cast on a piece of paper and completed his profile in pencil, paying close attention to the delicately rendered eyebrows and eyelids, as well as the stubble of his five o'clock shadow.[144]

---- The production of With My Tongue in My Cheek in the Spanish coastal resort of Cadaqués in the slimmer of 1959 is significant, since at that time Duchamp was preoccupied with rebuilding the Étant donnés mannequin after an unexpected heat wave in New York had left it severely damaged.[145] The year before, Duchamp and Teeny had spent the first of several summer vacations in Cadaqués, and before leaving had locked the mannequin and other works related to Étant donnés in the closet of his Fourteenth Street studio. When the couple returned from vacation, they discovered to their horror that the mannequin had suffered extensive damage due to the high temperatures, which had caused it to soften and crack. We know, for example, that the truncated right arm, visible in the early studies for Étant donnés, had fallen off, with the result that Duchamp had to shift the viewpoint slightly to obscure the fact that most of the limb was missing.[146] The extended arm holding aloft the Bec Auer light fixture also fell off and was irrevocably broken, requiring a separate form to be cast from Teeny's arm and clasped hand on their subsequentsummervacation in Cadaqués in 1959 (FIG. 2a.48).[147] As the photographer Denise Browne Hare pointed out, the hand holding the lamp is noticeably larger than the rest of the mannequin's body, thus adding a strange and uncanny sense of disproportion to what was already an unfathomable paysage fautif.[148]

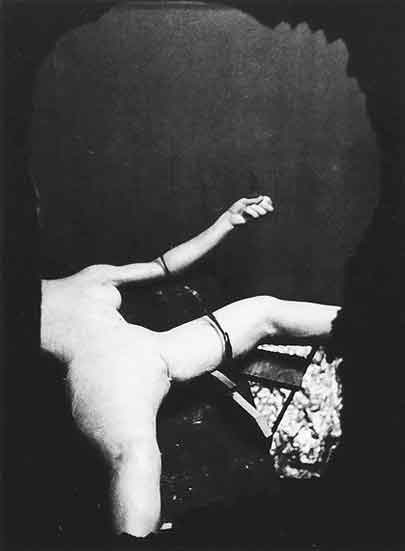

FIG. 2a.48

Marcel Duchamp

Untitled (Left Arm), 1959

PIaster, paint, shellac, pencil, and iron pin

8,7 × 38,3 cm (37⁄16 × 151⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mme Marcel Duchamp

---- Photographs confirm that Teeny's hands were indeed larger than those of the diminutive Maria Martins, explaining the discrepancy in scale between the cast hand and arm and the rest of the body (see fig. 2.38). Duchamp's photographs of the Étant donnés figure after the new hand and arm were attached to the existing body suggest that during the casting process Teeny held a pencil (see fig. 2.39), which served a purpose similar to that of the dowel held in the left hand of the plaster sculpture seen in the 1949 photograph (FIG. 2a.23 - Part 2), When removed, the space that remained where the pencil had been made it possible for Duchamp to pull an electrical wire through the hand to connect with and light the lamp.

Fig. 2.38

Unidentified photographer

Teeny Duchamp in front of an enlarged photograph of Marcel Duchamp

by Ugo Mulas (Italian, 1928-1973) at the Marcel Duchamp retrospective

exhibition, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973

Fig. 2.39

Marcel Duchamp

Slide photograph of the Étant donnés mannequin holding a pencil, c. 1965,

from the Dom Perignon Box (see FIG. 2b.5 - Part 5)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Paper.

Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- Adding a new and slightly larger hand and arm to the Étant donnés mannequin led Duchamp to reconsider the parameters of the surrounding brick aperture. After returning to his studio in the fall of 1959, the artist made a series of black-and-white photographs of the completed figure (FIG. 2a.49 and FIG. 2a.50 - Part 2), on one of which he outlined a new configuration for the bricks in red pencil. The new angle and pose of the left arm also may have encouraged Duchamp to alter the jagged brick framework so that it followed the contours of the extended arm in a much tighter arrangement that related to the changed orientation of the figure, which had shifted to the figure's right to obscure from view the damage inflicted on the right arm. It was thus in the fall of 1959 that the final position and viewing point of the female nude was established.

FIG. 2a.49

Marcel Duchamp

Photograph of a plaster study

for the figure in Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage, 1959

Gelatin silver print with red crayon

28,6 × 25,4 cm (111⁄4 × 10 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers,

in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

FIG. 2a.50

Marcel Duchamp

Photograph of a plaster study

for the figure in Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage, 1959

Gelatin silver print

28,6 × 25,4 cm (111⁄4 × 10 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers,

in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- That year, Duchamp made two copper-electroplated objects from the partial mold taken from Teeny's left hand (FIG. 2a.36 and FIG. 2a.37), the first containing the impression of the top two joints of her four fingers, clenched as though to hold the Bec Auer lamp, and the second the imprint of the thumb and wrist. These works have not been published or exhibited until now, but have a unique importance in Duchamp's oeuvre, since they clearly relate to the earlier series of erotic objects that the artist made from molds derived from the casting process of the Étant donnés figure. These highly polished objects have a different surface finish than those of the earlier pieces, although they retain the same sense of mystery and ambiguity, since they have the appearance of small-scale, abstract sculpture rather than forms derived from a human hand.

---- That Duchamp would create a relief plaster sculpture of his own cheek during this time is perhaps unsurprising, given his preoccupation with repairing the mannequin by means of new body casts in plaster, while the literal reference to tongue-in-cheek humor conforms to his public image as a mysterious hoaxer and master of mockery and irony. However, the work appears "less humorous on further reflection," as art historian Dalia Judovitz has argued: "The visual inscription of laughter (rire), associated with the tongue and cheek expression, congeals in this image with the rictus of death, the spasm of the face captured by the nineteenth- century death mask. Intended to celebrate and commemorate famous artists by capturing their lifelike likeness in plaster molds applied to the face and sometimes to the hands, the death mask ironically preserves the illusion of life through the image of death."[149]

---- The plaster cast of the artist's swollen cheek is inextricably linked to the complex casting techniques used by the artist to construct the recumbent female nude in Étant donnés. As discussed, Duchamp took private lessons in body casting from Ettore Salvatore in order to master these skills. In the life mask of Duchamp made by Salvatore himself, the cadaver-like visage with closed eyes appears not as an index of life but as an icon of death (see fig. 2.1). In contrast, With My Tongue in My Cheek is full of life-affirming vitality. The slit in the mouth and the long eyelashes drawn in pencil add details that would not have been included in a posthumous cast, while the swollen cheek remains marvelously pliant and supple, with none of the rigidity and immobility of a death mask. As a nondeath mask, Judovitz convincingly argues, this self-portrait "stages life and death, language and image, humor and dead-seriousness, as a series of contextual frames on which hinges Duchamp's statement about the conditional future of the artist as 'life on credit.'"[150]

---- Torture-morte is the second of the three multimedia relief constructions Duchamp submitted to Lebel in the summer of 1959 for their unrealized collaborative publication. The work consists of a painted plaster cast of a foot, possibly an imprint of the artist's own right foot, that was covered by a swarm of thirteen synthetic flies and placed on a paper background before being mounted vertically on a wooden support. The title is a macabre pun on nature morte, the French term for "still life," leading many commentators to read the words in literal terms, as a condemnation of the tired and outmoded convention of still-life painting as a dead (morte) genre.[151] However, the "torture" involved in the title may refer not to Duchamp's exasperation with the tradition of still-life painting, but rather to the flies that tormented the artist during his summer vacations in Cadaqués.[152]

---- As emblems of decomposition, the flies also denote death and decay, suggesting that Duchamp's own mortality was very much on his mind during the making of the self-portrait triptych. It was common in the Middle Ages to take molds of the feet of a recently deceased king or queen, as well as their death masks, in order to make posthumous portraits.[153] Duchamp's positive cast of a human foot thus makes reference to a by-product of the death rites of royalty, and perhaps even to the relics of the saints, just as With My Tongue in My Cheek speaks to the transfigured face of the death mask as a salute to the iron laws of life and death. By the twentieth century, however, these regal body casts had become a simple technical aid used in the sculptor's studio, since plaster effigies and death masks had long been relegated to the status of dusty stage props, much like the defunct plaster casts of the academy or the thousands of copies of the death mask of the so-called L'Inconnue de la Seine (The Unknown Woman of the Seine) that were once placed in the windows of shops selling artist's materials, as a tempting invitation to draw or sculpt a version of the drowned waif's strange, angelic face (see fig. 2.40).[154]

Fig. 2.40

Unidentified photographer

The death mask of L'Inconnue de la Seine, c. 1900

---- That Torture-morte tapped into an existing iconography of death and embalmment, one related to Duchamp's ruminations on his own mortality, is supported by the artist's apparent reference through his cast instep to Andrea Mantegna's Lamentation over the Dead Christ, in which the soles of Christ's chalky gray feet are shown through a remarkable use of foreshortened perspective (see fig. 2.41). Duchamp's interest in perspective was revived during the planning and construction of the viewer's sight lines in Étant donnés, perhaps drawing rum to Mantegna's famous devotional painting, which similarly presents a seemingly life-size, truncated figure, depicted in a frontal, dramatically foreshortened view, lying flat on a stone table in an interior setting.[155] In 1946, Duchamp employed a similar perspective in his delicately shaded drawing of Maria Martins's right foot (FIG. 2a.5 - Part 1), thus suggesting that Mantegna's painting was on his mind at the inception of his Étant donnés project. Mantegna's picture was devised to be hung at eye level, as it is today at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, so that the spectator's attention is arrested by the soles of the livid gray feet as they extend beyond the edge of the marble funeral slab. The viewer is immediately confronted with the open wounds on Christ's feet, as well as his discolored and decaying flesh, which resembles torn paper. Directed by the axial lines of the folds of Christ's loincloth, the viewer's eyes then move up the body to the wounds in the hands, similarly hideous and gut-wrenching. The use of extreme foreshortening, one-point perspective, and illusionism intensifies the emotional impact of the wounds and suffering of Christ to create a majestic yet touching representation of death. The allusions to personal suffering in Torture-morte — perhaps including Duchamp's discomfiture during the casting process and the swarm of flies that bothered him that summer — evoke the dark, open wounds on Christ's feet in Mantegna's painting, whose transcendent realism resonates with the twentiethcentury artist's phantasmic tableau-construction.

Fig. 2.41

Andrea Mantegna (ltalian, c. 1431-1506)

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c. 1480

Tempera on canvas, 68 × 81 cm (263⁄4 × 317⁄8 inches)

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

---- For Sculpture-morte, the third work in the triptych, Duchamp commissioned from the pâtissier Bonnevie in Perpignan, just across the French border from Cadaqués, several pieces of touron, a hard pastry consisting of hazelnuts, almonds, and marzipan, which he used to construct a trompe l'oeil self-portrait (fig. 2.42).[156] The preserved composition features edible vegetables as well as a cherry, bumblebee, and beetle on wrapping paper mounted on a Masonite support. As with the fantastic fusion-faces of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the sixteenth-century Italian painter who specialized in composite heads and allegorical figures made of fruits, flowers, vegetables, plants, and grains (fig. 2.43), Duchamp's assortment of touron delicacies coalesces into a self-portrait in profile. While the emotive effect of Mantegna's recumbent corpse is achieved through the virtuoso use of foreshortening, Arcimboldo's figural gestalts are dependent on a different type of optical illusionism, that of the reversible "double" image, in which one form assumes the semblance of another after being stared at intently. Taking advantage of the slightest coincidences of shapes and colors, Arcimboldo ingeniously transformed one image into another, and the brilliant artifice of his witty vegetal fantasies may have appealed to Duchamp for their nonretinal qualities, since the alteration of the fruits and vegetables into recognizable facial features took place in the mind of the viewer.

Fig. 2.42h

Marcel Duchamp

Sculpture-morte, 1959

Assemblage: insects, fruits, and vegetables in touron on paper mounted on Masonite,

in box of wood and glass, 33,8 × 22,5 × 9,9 cm (135⁄16 × 87⁄8 × 37⁄8 inches)

Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Fig. 2.43

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (Italian, 1527-1593)

Flora, c. 1591

Oil on wood panel, 72,8 × 56,3 cm (285⁄8 × 221⁄8 inches)

Private collection, Paris

---- The use of double configurations had earlier appealed to the Surrealists, especially Salvador Dalí, whose paintings of the late 1930s featuring paranoiac double imagery owed a considerable debt to Arcimboldo's earlier composite heads and figures. As we have seen, in the summer of 1959 Duchamp saw a great deal of Dalí while the two artists worked together on the collotype print edition of the landscape. It is possible that they discussed their shared interest in Arcimboldo at this time. Another, more likely explanation for the genesis of Sculpture-morte may reside with Robert Lebel, who was a recognized authority on Arcimboldo and owned an important sixteenth-century painting of a composite head entitled Flora, which had recently been down, graded to the work of Francesco Zucchi (although the original attribution to Arcimboldo has since been restored).[157] Given the collaborative nature of the proposed publication by Lebel and Duchamp, the artist may have chosen to portray himself in a style that paid honor to his friend's expertise on the Italian painter. At the same time, Arcimboldo's vegetative sources suggest the inevitability of death and decay, a theme that coincided with Duchamp's current interests, as seen in Torture-morte.

---- Beyond his deliberate references to art history, including the triptych format itself, the three components of Duchamp's collective self-portrait also allude to his own shifting, fragmented persona, as seen in the earlier provocative Rrose Sélavy gesture, which had questioned fixed notions of identity and authorship. Like Arcimboldo's delirious fabrications, Duchamp's relinquishment of a fixed identity meant that his fluid self-image always hovered chimerically between complete openness and deliberate obfuscation.

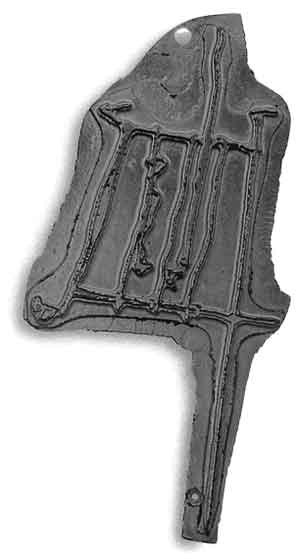

---- Another work that Duchamp made in 1959 was Éclairage Intérieur (Interior Lighting; FIG. 2a.51), a small zinc block that reproduced in shallow relief a line drawing accompanying the note bearing the same title in The Green Box. This block was used in printing the anthology of Duchamp's writings, Marchand du sel, which was edited by Michel Sanouillet and published in Paris by Le Terrain Vague in 1958. In June 1959, Duchamp had the zinc block gold-plated before presenting it to Sanouillet's wife, Anne, as the pendant for a necklace. Unbeknownst to both Michel and Anne Sanouillet, Duchamp used another cast of Éclairage Intérieur for the ingenious waterfall mechanism of Étant donnés. The artist removed the linear, low-relief pattern, based on the sketch in The Green Box, from the zinc block and placed the fragile filaments in front of the lightbulb to disseminate the flickering light throughout the interior. Embedded in the landscape backdrop and placed behind a small piece of translucent plastic, the linear design is invisible from the eyeholes in the wooden door, but without the presence of these filaments the waterfall would lose its impression of cascading water.

FIG. 2a.51

Marcel Duchamp

Éclairagr intérieur (Interior Lighting), 1959

Gold-plated zince block

7,3 × 3,5 cm (27⁄8 ×13⁄8 inches)

Collection of Anne Sanouillet

Part 1 Part 2 ---- Part 4 Part 5

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 88-99, 123-124. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[124] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Louise and Walter Arensberg, May 8, 1949, in Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk, trans. Jill Taylor (Ghent, Belgium: Ludion, 2000), p. 272.

[125] See Gertrude Benson, "Duchamp Masterpiece Installed at Art Museum," Philadelphia lnquirer, July 25, 1954, pp. 1, 4. According to this article, the seven-hundred-pound Large Glass was installed by fifteen men under the supervision of Duchamp, Henri Marceau (the Museum's Associate Director), and George Barbour (the Building Superintendent).

[126] In a letter to Henri Marceau dated April 7, 1954, Duchamp suggested that The Large Glass should not be positioned exactly in the middle of the gallery, but nearer the window wall. The artist sketched for Marceau a plan of his proposed installation, in which The Large Glass was for the first time placed in front of a small door leading to an exterior balcony. Duchamp also enclosed for Marceau a photograph of The Large Glass as it was installed in Katherine Dreier's home in Connecticut, where it was placed in front of a window so that the viewer could look outside at a garden containing Brancusi's sculpture Leda (1925). As Duchamp's letter made clear, he intended the door at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to function in a similar manner, thus allowing visitors to see the Museum's East Terrace, including Martins's sculpture, through the transparent panes of The Large Glass when the door was opened; Marcel Duchamp, letter to Henri Marceau, April 7, 1954, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Fiske Kimball Records, General correspondence and related material, 1953-54, box 93, folder 15.

[127] Dieter Daniels was the first scholar to recognize the importance of Duchamp's addition of the doorway in 1954. The installation of Étant donnés in an adjacent gallery fifteen years later thus ensured that Martins's nude body was visible both inside and outside the Museum, as Duchamp no doubt intended when he selected the gallery for his final work; see Daniels, Duchamp und die anderen: Der Modelfall einer künstlerischen Wirkungsgeschichte in der Moderne (Cologne: DuMont, 1992), p. 285.

[128] Evan H. Turner, interview with the author, Philadelphia, July 8, 2008.

[129] As Karen Wonders has pointed out, the trompe l'oeil realism of Duchamp's Étant donnés recalls the illusionistic scenarios of the habitat dioramas found in natural history museums, which re-create for the viewer the spatial sensation of a distant painted panoramic landscape filled with zoological specimens and other aspects of the natural world; see Wonders, Habitat Dioramas: Illusions of Wilderness in Museums of Natural History (Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University, 1993), pp. 227-28.

[130] See Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp: The Box in a Valise, trans. David Britt (New York: Rizzoli, 1989), p. 153.

[131] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 2.

[132] Richard Hamilton, interview with the author, Northend, Oxfordshire, UK, May 27, 2008.

[132-a] Beth A. Price, Ken Sutherland, Scott Homolka, and Elena Torok, "Evolution of the Landscape: The Materials and Methods of the Étant donnés Backdrop" in Michael R. Taylor; "Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés," Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, p. 269.

[133] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 2.

[134] See Sandra Rauschenberger, "Matisse Slept Here," Hunterdon Life (Flemington, NJ), vol. 1, no. 12 (August 2005), pp. 16-17.

[135] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 2.

[136] Peter Read, "The Tzanck Check and Related Works by Marcel Duchamp," in Rudolf Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), p. 103.

[137] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Lawrence D. Steefel, Jr., "The Position of La Mariée mise à nu par ses Céilibataires, même (1915-1923) in the Stylistic and Iconographic Development of the Art of Marcel Duchamp," PhD diss., Princeton University, 1960, p. 312.

[138] Robert Lebel's son, Jean-Jacques Lebel, suggested in a recent interview that the project "had to do with Arnold Fawcus of Trianon Press," but the exact details of the proposed publication remain unclear; Lebel, quoted in Paul B. Franklin, "Coming of Age with Marcel: An Interview with Jean-Jacques Lebel," Étant donnés Marcel Duchamp, no. 7 (2006), p. 21.

[139] Robert Lebel, "Duchamp au musée," in Jean Clair, ed., Marcel Duchamp, vol. 3, Abécédaire (Paris: Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1977), p. 123; trans. and repr. in Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (1997), vol. 2, p. 820. The idea of a second publication, containing illustrations of the three new works that Duchamp was to make that summer, was suggested as early as April 1959. In a letter dated April 15, 1959, Duchamp asked Lebel, "When do you need the 3 illustrations? I hope not before July because in principle I accept, but will I have the pleasure of pleasing the both of us?"; Marcel Duchamp, letter to Robert Lebel, April 15, 1959, quoted in Franklin, "Coming of Age with Marcel," p. 20.

[140] A. V. [Anita Ventura], "Marcel Duchamp," Arts Magazine (New York), vol. 33, no. 8 (May 1959), p. 59.

[141] Jean-Jacques Lebel, letter to the author, December 1, 2008.

[142] See Henderson, Duchamp in Context, pp. 104, 217.

[143] The circumstances surrounding Duchamp's execution of Du Tignet were first uncovered by Hellmut Wohl; see "Beyond the Large Glass: Notes on a Landscape Drawing of Marcel Duchamp," Burlington Magazine, vol. 119, no. 896 (November 1977), pp. 763-72.

[144] See Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, p. 406.

[145] Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, interview with the author, Villiers-sous-Grez, France, March 30, 2007. I am thankful to the artist's stepdaughter for providing this crucial, previously unpublished information about damage to the Étant donnés mannequin in the summer of 1959.

[146] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 1.

[147] Ibid. Teeny Duchamp provided further details regarding the broken left arm and Duchamp's efforts to cast her own arm and hand in an interview with the author, Rouen, May 10, 1994.

[148] See Browne Hare, "Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés in His New York Studio," p. 30. Unaware that the cast had been taken from Teeny's arm and clenched hand, Browne Hare speculated that this enormous, mannish hand was "larger than a woman's — possibly closer in size to the artist's."

[149] Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), p. 117.

[150] Ibid.

[151] Judovitz, for example, sees the work as staging "the death of painting and sculpture both literally and figuratively"; ibid., p. 151.

[152] See Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, entry for June 30, 1959, Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), unpaginated.

[153] According to Ernst Benkard, this practice began with the death of Charles VI of France in 1422, when the court painter Maître François d'Orleans made the king's death mask, as well as molds of his hands and feet, for the purpose of executing a magnificent posthumous portrait of the deceased monarch; Benkard, Undying Faces: A Collection of Death Masks, trans. Margaret M. Green (New York: Norton, 1929), p. 21.

[154] See Walter Sorell, The Other Face: The Mask in the Arts (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973), pp. 209-10. The Unknown Woman of the Seine fascinated modern artist, especially René Magritte, Man Ray, and other members of the Surrealistic group. For more on the twentieth-century artistic reception of this life mask, see Hélène Pinet, "L'Eau, la femme, la mort: Le Myth de l'Inconnue de la Seine," in Emmanuelle Héran, ed., Le Dernier portrait, exh. cat., Musee d'Orsay (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002), pp. 175-90.

[155] For an erudite account of Duchamp's lifelong interest in the "rehabilitation of perspective," see Jean Clair, "Duchamp and the Classical Perspectivists," Artforum, vol. 16, no. 7 (March 1978), pp. 40-49.

[156] See Gough-Cooper and Caumont, entry for June 30, 1959, Ephemerides.

[157] Although Lebel firmly believed that his painting was made by Arcimboldo, in the 1950s the work was reattributed to Zucchi by Francine-Claire Legrand and Félix Sluys; see Legrand and Sluys, Giuseppe Arcimboldo et les arcimboldesques (Paris: La Nef, 1955), p. 93. Pontus Hultén reattributed Flora to Arcimboldo in 1987; see Hultén, ed., The Arcimboldo Effect: Transformations of the Face from the 16th to the 20th Century (New York: Abbeville, 1987), p. 161.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES