Michael R. Taylor

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 1

GENESIS

(Part 2)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 26-32.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

MARIA, ENFIN ARRIVÉE

Born Maria de Lourdes Alves in 1894 in Campanha, Brazil, a town in southern Minas Gerais, Maria Martins was the mother of three teenage children and an established artist in her own right by the time she met Duchamp, who was seven years her senior. In the winter of 1941-42, Martins moved to New York, where she rented a three-bedroom duplex apartment, at 471 Park Avenue at Fifty-eighth Street, with a high-ceilinged studio on the ground floor, and began taking lessons from the Lithuanian-born sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, a master of the lost wax (ciré perdu) method of bronze casting. Martins's apprenticeship with Lipchitz during these two years, when they worked side-by-side within the narrow confines of his one-room studio at 42 Washington Square South, led to a brief yet tumultuous love affair. Martins's suitors of the early 1940s, whose number also included Fernand Léger and Piet Mondrian,[16] appear to have been attracted to the point of obsession with her physical beauty, sexual freedom, and irrepressible personality. According to her daughters, Martins was a classic femme fatale, "a woman who did whatever she needed to get men to fall in love with her, while never falling in love herself," thus ensuring that the vast majority of these unrequited love affairs were ill-fated and consequently short-lived.[17] This recollection is confirmed by a prose poem Martins wrote in the mid-1940s that provides some idea of how she felt about the various men who came under her spell: "Even long after my death / Long after your death / I want to torture you. / I want the thought of me / to coil around your body like a serpent of fire / without burning you. / I want to see you lost, asphyxiated, wander / in the murky haze; woven by my desires. / For you, I want long sleepless nights / filled by the roaring tom-tom of storms / Far away, invisible, unknown. / Then, I want the nostalgia of my presence; to paralyze you."[18]

---- The baroque expressionism of Lipchitz's allegorical figurative sculptures would have a decisive impact on Martins's future work, and her interest in Brazilian folklore and her voracious sexual appetite would have an equally profound influence on Lipchitz's own work between 1941 and 1942, when he completed an important series of twelve transparent sculptures that were shown in 1943 to great critical acclaim at Curt Valentin's Buchholz Gallery in New York. It was likely Martins who inspired Lipchitz to create orgiastic sculptures like Blossoming (1941-42), in which a woman's nude body bursts out of a spiky form resembling tropical fruit, perhaps a pomegranate or pineapple (fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

Jacques Lipchitz

Blossoming, 1941-42

Bronze, 54.6 × 41.9 × 41.6 cm (211⁄2 × 161⁄2 × 163⁄8 inches)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Given anonymously, 1943

Fig. 1.6

Jacques Lipchitz

Yara I (Yara assise), 1942

Bronze, h. 55.9 cm (22 inches)

Formerly collection of Maria Martins

---- Lipchitz's intense and often stormy relationship with Martins helps to explain the dramatic change that his own work underwent in the early 1940s, when he began to create highly emotional and freely expressive works modeled directly in wax and cast in bronze in unique editions. Another work from this period, Yara (fig. 1.6), includes exposed female genitalia, and when pressed by art historian Deborah Stott, in a 1968 interview, to explain the vaginalike cleft and spiny pubic hair in this sculpture and other related works, he simply stated that the pieces were "very hot" and that "this woman [Maria Martins] was very hairy."[19] "They are very curious things," Lipchitz continued, but he could not explain how they came about "except to say that they came from a man who was in love." He described these spontaneously conceived works as the erotic products of his imagination, which had been stimulated by his passionate affair with Martins, as well as by her interest in her rich native culture, including Amazonian deities, animism, dance and music, especially the samba, and above all the myths and legends of the Brazilian rainforest.[20] Lipchitz's Yara, one of two sculptures on this theme that the artist made in 1942, was inspired by Martins's account of a folk legend, based on Tupi or Guarani mythology, regarding a man-eating siren of the Amazon River. According to Martins's unique understanding of the myth, Yara was a river goddess who spent her days sitting on the large crimson-hued lotus plant known as Vitoria regia, while combing her hair or basking in the sun. Whenever she sensed a man approaching, Yara would sing "her song of seduction" to entice the ill-fated lover to visit her jungle domain, where she would "offer him a flower and the kiss of death" before devouring him like an insect in a Venus flytrap.[21]

---- Lipchitz's first version of Yara depicts a nude Martins as the Amazonian river goddess, rearing up on a huge water-lily pad as if poised to catch and digest yet another poor mortal who cannot resist her song of temptation. In his second version, the artist endowed Martins with multiple breasts, like an ancient fertility goddess, although his intention simply may have been to convey a sense of increased sexual potency designed to lure and destroy the male prey that fell under her spell. Lipchitz appears to have conflated the folkloric origins of these sculptures with his own feelings for Martins, in which sexual attraction was mixed with fear and trepidation: "The man comes and she closes the net on him like a trap ... if you come here you are finished." In her interview notes, Deborah Stott added, "[Lipchitz] doesn't know how he escaped! That was his feeling at the time: He was ready to be eaten up, it didn't matter; he was going to be eaten up with great passion."[22]

Fig. 1.7

Maria Martins (Brazilian, 1894-1973)

Yara, c. 1940

Painted plaster, 207.6 × 71.1 × 73.7 cm (813⁄4 × 28 × 29 inches)

Installed on the East Terrace of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1940

---- Two years earlier, in 1940, Martins had submitted her own, plaster version of Yara to an international exhibition of contemporary sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. 1.7). Painted to resemble bronze, the nearly eight-foot-high sculpture graced the Museum's East Terrace, overlooking Philadelphia's City Hall and Center City, and was one of the most talked-about works on display. The following year, it was included in the artist's solo exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where it was identified by C. Powell Minnigerode, the museum's director, as a water sprite rising like a fountain from a base decorated with fish and other sea forms.[23] Two years later, under Lipchitz's supervision, Martins cast this tall standing nude in bronze for her solo exhibition at the Valentine Gallery in New York, which opened on May 11, 1942.[24] That same year the sculpture was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the relatively large sum of $10,000, and on July 6 the work was installed on a limestone base in an outdoor sculpture garden on the Museum's East Terrace, where it overlooked a spurting fountain (fig. 1.9).[25] The site was appropriate, given Martins's interest in the water myths of the Amazonian rainforest, as seen in the fishlike forms that cover the base of the sculpture and the droplets of water that run down the figure's back and legs, suggesting that originally it was intended as a fountain. The placement of the work would take on added significance in 1954, when Duchamp installed a gallery featuring his Large Glass in the modern wing of the Museum (fig. 1.8). Following Duchamp's specific instructions, behind his magnum opus a small doorway was installed that led onto a balcony, allowing visitors to walk outside the gallery designated for his piece and take in a commanding view of Martins's sculpture on the East Terrace below.

Fig. 1.8

View of The Large Glass installed in the Arensberg Collection, Gallery 1729,

at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1965;

center right, the door to the balcony overlooking the East Terrace

Fig. 1.9

Maria Martins

Yara, 1942

Bronze, 207.6 × 71.1 × 73.7 cm (813⁄4 × 28 × 29 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with funds contributed by an anonymous donor, 1942-72-1

---- In a 1942 interview, Henri Marceau, the Museum's Assistant Director, correctly intuited that Yara dealt "with subject-matter inspired by the rich semi-mystic folk lore and legend of Brazil" before going on to praise the artist's working methods: "Her treatment of form, her design and her skillful surface textures are personal and original. The moods created are direct and vital expressions of vast new sources as yet unknown in our own hemisphere. Her language is that of realism combined with fanciful gesture—time tested methods but, in this case, employed with youthful intelligence and enthusiasm."[26] Marceau's keen endorsement of Martins's work followed the end of her relationship with the avuncular Lipchitz, who clearly was intimidated by her frank sexuality and dominant personality, and perhaps by her growing independence as a sculptor. Rejecting the classical surface treatment of works like Yara, which one critic had compared to the academic realism of the French sculptor Émile-Antoine Bourdelle,[27] Martins's sculpture underwent a profound metamorphosis in 1942, partly in response to the subtle interplay between convex and concave forms in Lipchitz's work, but also as a result of her exposure to the work of the exiled Surrealist group in New York.

---- The bronze sculptures that Martins produced after her training with Lipchitz ended in 1942 reveal her continued fascination with the mythology of the Amazon rainforest, but the human, plant, and animal forms she used were no longer presented in the static, timeworn fashion of the standing nude in Yara. Instead, her works became animated with a writhing, baroque exuberance that accentuated her themes of fertility, desire, and sexual cruelty. In the mysterious bronze sculpture Cobra grande (1942), the undulating form of an Amazonian snake deity is repeated in a dense archway of entangled cords and vines evocative of the impenetrable Amazon jungle over which she presides (fig. 1.10). According to art historian Katia Canton, in this work and other bronze sculptures of the 1940s Martins created "a remarkable amalgam, where men and women, animals, forests and swamps appear to echo sensuality. She manipulates images, imbuing them with desire, violence and lyricism and in doing so, ascribing to them a mythical condition. In particular, bronze is treated in such a way that through autonomous nuances, it replicates the organic nature, the textures and porosity of the human skin and of natural sap."[28]

Fig. 1.10

Maria Martins

Cobra grande, 1942

Bronze, 40.6 × 52.1 × 31.1 cm (16 × 201⁄2 × 121⁄4 inches)

Private collection

---- Martins described the great snake goddess depicted in Cobra grande as having "the cruelty of a monster and the sweetness of wild fruit,"[29] a characterization that she perhaps applied to herself. Her fiery temperament ultimately led to her breakup with Lipchitz, whose fragile state of mind can be discerned in several works from this time that resemble threatening cagelike structures covered with spikes and tendrils, far removed from the rhapsodic nature of Blossoming, a work made at the beginning of their affair. Another terrifying sculpture from 1942, entitled Myrrah, consists of a disemboweled female pelvic region, replete with sharp excrescences, which can be read as a vagina dentata.[30] Lipchitz's clichéd descriptions of Martins as an archetypal praying mantis-like figure reveal that he saw this powerful, independent woman as an "exotic" Other, whose unpredictable nature and aggressive sexuality simultaneously attracted him and scared him half to death. Perhaps unsurprisingly, when Lipchitz abruptly ended the relationship in the fall of 1942 he returned to his conventional marriage with the poet Berthe Kitrosser, following a narrow escape from what he perceived to be the clutches of a ferocious, man-eating goddess whose siren call he was doomed never to forget.[31]

---- That Martins's relationship with Duchamp lasted for almost a decade implies a different dynamic for their love affair, in which her emotional volatility contrasted with the older artist's cool detachment. Their different temperaments presented insurmountable problems for the relationship, leading Martins to use their incompatibility as the subject of perhaps her greatest work, entitled Impossible, which she produced in multiple versions in plaster and bronze (see fig. 1.11). Drawing on the sculptor's earlier interest in sexual imagery related to Venus flytraps and other types of predatory animal and plant forms, the work depicts a male and a female figure doomed to exist together in perpetual combat, symbolized by their interlocking tentacles. That Martins intended these terrifying ovoid-headed figures to represent the underlying problems of her relationship with Duchamp can be discerned from her comments on the work to Time magazine in 1946: "The world is complicated and sad—it is nearly impossible to make people understand each other."[32]

Fig. 1.11

Maria Martins

Impossible III, 1946

Bronze, 80 × 82.6 × 53.3 cm (311⁄2 × 321⁄2 × 21 inches)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase, 1946

---- Despite her earlier reputation as a femme fatale who cruelly tortured the men with whom she was romantically involved outside her marriage, Martins appears to have met her match in the cerebral Duchamp, who was fifty-nine years old in 1946 and had learned during the course of his lifetime to carefully guard his emotions. As recalled by his close friend the Surrealist art dealer Julien Levy, Duchamp's own feelings for Martins swung like a pendulum between infatuation and indifference: "Marcel must have enjoyed [the] vicarious 'home life' which Mary Reynolds gave him and also Maria Martins. Marcel would happily stay with Maria Martins in her hotel suite in New York in the 1940s and take baths and be looked after for a while, then would disappear down to this Fourteenth Street studio where she was not allowed to follow him."[33]

---- The strong sexual desire Duchamp felt for Martins became the dominant focus of his work, as seen in the mysterious, mucilaginous landscape that the artist mounted inside the lid of the Boîte-en-valise (literally, "box in a suitcase") he gave to Martins in Paris on April 6, 1946.[34] This intimate work, entitled Paysage fautif (FIG. 1-A4), depicts a limpid, amorphous landscape on transparent Astralon backed with black satin, redolent of soiled stockings or lingerie, and anticipates the hilly backdrop of Étant donnés. The viscous substance used to create the work was later identified as seminal fluid, and speaks to the passionate nature of the artist's affair with the ultimately unattainable Martins, as well as to the difficulties of controlling the flow of ejaculated semen, as intimated by the title, which translates as "wayward (or faulty) landscape."[35] The "faulty" aspect of the work's title also can be applied to the false reality and the anatomical awkwardness of the simulacral nude and her painstakingly constructed environment in Étant donnés, where the mixture of the real and the handcrafted, and the deformations of the mannequin's genitals, signal to the viewer that something is wrong or slightly askew in this strangely artificial scene.

---- Several Duchamp scholars have interpreted the gestural "splash" of Paysage fautif as an expression of the artist's misgivings about the "retinal" nature of Abstract Expressionism,[36] but the use of semen was more likely intended as a humorous allusion to the work of his contemporaries in the Surrealist group, such as André Masson and Arshile Gorky, whose nature-based paintings of the 1940s were filled with abstracted images of fecundity and procreation, including swollen genitalia, bursting seeds, and other organic forms. Duchamp and Martins were fully conversant with the erotic nature of these artists' landscape paintings. Gorky's and Masson's works offer a more believable point of reference than, say, Jackson Pollock's ejaculatory "drip" paintings, which he did not begin producing until the year after Duchamp completed Paysage fautif.

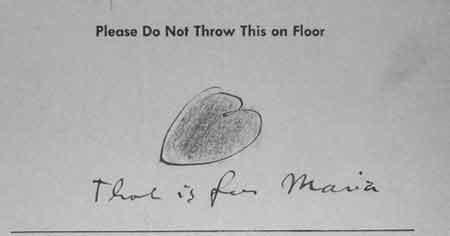

FIG. 1-A3

Marcel Duchamp

That Is for Maria (Please Do Not Throw This on Floor), c. 1946

Ink and crayon on printed notepaper

7.6 × 14 cm (3 × 51⁄2 inches)

Private collection

![Marcel Duchamp: Paysage fautif (Wayward of Faulty Landscape), 1946. Marcel Duchamp - Paysage fautif (Wayward of Faulty Landscape), 1946 - Original painting from the deluxe edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise) - (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in Valise]) - Seminal fluid on Astralon backed with black satin - 21×16.5 cm (8¼×6½ inches) - The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama, Japan](35/F-A4-Marcel-Duchamp-Paysage-fautif-Wayward-of-Faulty-Landscape.jpg)

FIG. 1-A4

Marcel Duchamp

Paysage fautif (Wayward of Faulty Landscape), 1946

Original painting from the deluxe edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise)

(From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in Valise])

Seminal fluid on Astralon backed with black satin

21 × 16.5 cm (81⁄4 × 61⁄2 inches)

The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama, Japan

---- In 1946, when Duchamp gave Martins his Boîte-en- valise with its peculiar landscape composed of ejaculated seminal fluid, he also presented her with a deluxe version of The Green Box in which he had enclosed additional items—several further notes and an important study for The Large Glass, as well as the second issue of The Blind Man, a Dada magazine that the artist had coedited in 1917.[37] Inside the copy of The Green Box that he gave to Martins, Duchamp had placed a large and rather thick piece of white drawing paper, folded in half and bearing on one side a handwritten dedication in black ink that reads "pour Maria, enfin arrivée" (for Maria, [you have] finally arrived). This enigmatic inscription contains a double entendre that refers to sexual climax during lovemaking, and also suggests that the artist's enduring relationship with Martins had recently grown in intensity and fulfillment for both parties. It is therefore no coincidence that Duchamp began work in the same year on the construction of the Étant donnés mannequin, which required Martins to undergo long sessions of body casting. Whereas Martins's earlier relationships had failed due to her femme fatale persona, it would seem that her apparent incompatibility with the often distant and detached Duchamp may have worked in their favor, since neither party had the upper hand in the affair. The result was a more intimate and less fraught romance, which at least in the short term suited their respective personalities. An undated drawing of a heart that Duchamp gave to Martins underscores the depths of his feelings for her, as well as his fear of a painful breakup in the near future (FIG. 1-A3). The crudely drawn heart was rendered in ink and red crayon on a scrap of notepaper bearing the printed instruction "Please Do Not Throw This on Floor. "When seen in conjunction with Duchamp's handwritten dedication, "That is for Maria," placed underneath the heart, this poignant drawing can be read as a Valentine to his new love—as well as a reflection of his fears that one day she would callously rip out his heart, stomp on it, and leave it on the floor.

---- Unlike Lipchitz, who appears to have been threatened and unsettled by Martins's aggressive sexuality, Duchamp's letters to Martins reveal that he embraced her passionate and thoroughly independent nature, and foresaw a life of love and happiness together in which she would rent a studio next door to his cramped quarters on Fourteenth Street, where he would begin work in 1946 on Étant donnés.[38] Unpublished until this volume, thirty-five letters written sometime between 1946 and 1952, with one final missive written between November 1967 and March 1968, contain invaluable insights into their relationship. In one of the first letters, written in late 1946 or early 1947, Duchamp invited Martins to join him in his studio, despite his preference for being alone: "I actually like being alone here in the studio. This solitude is, in fact, just a way of re-entering my own individuality and it gives me an illusion of freedom inside 4 walls. But there is room enough for two if you want to be as one with my freedom, and a greater freedom still will come of it, as yours will protect and foster mine, and mine yours, I hope."[39]

---- Scholars who have had access to this cache of love letters often have misrepresented their contents.[40] While there are frequent references to the couple's sexual relationship, as when Duchamp asked Martins to "kiss my flower for me,"[41] the letters are by no means scandalous or even titillating, but rather the expression of one adult's love for another. Although filled with endearments like "my little one"[42] and heartfelt declarations such as "I would like to breathe with you,"[43] Duchamp does not come across as a helpless, lovesick puppy as so often has been claimed, but rather appears to have approached the breakdown of his relationship with Martins, toward the end of the 1940s, as a sad yet almost inevitable event, given their opposing temperaments and her preexisting family obligations. Occasionally wistful and even vulnerable, especially when they were apart and he clearly missed her, Duchamp also conveyed his impatience with Martins's "susceptibility problem," by which he meant her stubborn refusal to commit to the life of an artist rather than that of a popular socialite who loved to throw extravagant parties and mix with the chic upper echelons of Washington's diplomatic corps.[44]

---- From the very beginning, Duchamp hoped to love Martins "simply and purely," without the "vaudeville farce that generally accompanies the trials and tribulations of two lovers."[45] The letters also reveal that the older artist was an important mentor to Martins at a time when she aspired to be a modern sculptor associated with the international Surrealist movement. However, his insistence that she leave behind her glamorous friends and champagne parties—in 1946 Time magazine described Martins as "dynamically sociable"[46]—and devote herself solely to her work and their relationship fell on deaf ears. The popular, party-loving Martins was not prepared to leave her husband, children, and friends, and to embrace Duchamp's spartan lifestyle. He argued that the antidote to the "gang of so-called 'friends' who are not out to do us any wrong as such but who simply want to keep us in a cage," was for Martins to work exclusively on her sculpture and for Duchamp to devote himself to the completion of "my woman with the open pussy," as he called the Étant donnés mannequin.[47]

---- The closed, hermetic world that he imagined for the two of them was incompatible with Martins's own attempts to juggle her family commitments with her art world ambitions, and by 1949 Duchamp was already looking back on happier times in their relationship, when they had met at her apartment at 471 Park Avenue: "I have started to dream about number 471, as that is where we had our best times, and to relive them will be joy redoubled."[48] As Duchamp readily admitted in a subsequent letter, dated June 6, 1949, "We are still a long way off from the secular convent we had dreamed for ourselves. I believe more and more in an absolute retreat from the world—5 friends at most. For the rest: silence, total and complete, stubborn silence."[49] These ironic and often deliberately blasphemous references to a secular convent or a monk's ceil, in which the couple could insulate and protect themselves from the rest of the world, are consistent with his belief that great artists should work "underground." This notion reemerges in later letters, when Duchamp imagined the studio in which he was constructing the Étant donnés mannequin as "the beginning of our monastery. You could isolate yourself here with me and nobody would be aware that this cage away from the world even existed."[50]

---- The frequent allusions to monasteries and convents also may have been part of an extended private joke between the couple, since in three of his letters to Martins the artist described the nude mannequin as "N.D. [Notre Dame] des désirs" (Our Lady of Desires), or some variant of this appellation, which can be understood as a humorous and sacrilegious term of endearment that speaks to their shared involvement in Étant donnés. The blasphemous undertones of their secret project bring to mind Kurt Schwitters's transformation of his home at 5 Waldhausenstrasse in Hannover after World War I into a walk-through environmental installation featuring wooden columns and grottolike plaster-of-paris cavities, known today as the Merzbau (see fig. 1. 12).[51] Schwitters began work on this shrine to his obsessions in 1923, at which time he called it the Kathedrale des erotischen Elends (Cathedral of Erotic Misery), perhaps in reference to those personal items of a sexual nature that he placed inside the cavities of the architecture, with an effect reminiscent of religious displays of the relics of the saints.[52] Duchamp visited Schwitters's home on a visit to Germany with his American patron Katherine Dreier in 1929, at which time he no doubt explored the cavernous Merzbau environment, and his letters to Martins concerning "Our Lady of Desires" contain a sacrilegious undercurrent similar to that found in the German artist's cathedral-like installation.[53]

Fig. 1.12

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887-1948)

Hannover Merzbau, detail, view of blaues Fenster (Blue Window), 1933

(destroyed 1943)

---- Duchamp tried to persuade his Brazilian lover to abandon her family and begin a new life of personal freedom and erotic adventure in "a cage away from the world," but in the end Martins refused to enter the secular convent that he imagined for them. Following her husband's retirement from diplomatic life in 1950, the couple and their children returned to Brazil. Prior to his retirement, Carlos Martins had been posted to Paris, where he served as the Brazilian ambassador from April 1948 to November 1949. Although Martins moved to Paris with her husband, this temporary relocation did not affect her relationship with Duchamp, given his close ties to the French capital. However, Martins's decision to move permanently to Brazil presented a seemingly insurmountable geographical obstacle to the continuation of their love affair.

---- In a state of despair, Duchamp wrote a heartrending missive on March 19, 1950, explaining that he felt "totally lost now that we are completely cut off from each other."[54] In the following year, Duchamp confessed that he was "seized by blind rage every time I think not only of us but just of you as a living being created for a higher destiny, such as you feel it deeply yourself, and whose fulfillment is refused you, as when drowning in a dream and unable to reach the branch that is near."[55] Martins's "higher destiny" as an avantgarde sculptor had been put on hold while she met her duties as wife and mother, and Duchamp felt himself "drowning" in the desperate circumstances of her absence. He ended the letter lamenting, "Where are our happy days and happy nights?"[56] Martins's visit to New York in the fall of 1951 temporarily rekindled the artist's hopes, but those were soon dashed. "I am more and more convinced that our situation is hopeless," he told Martins on October 25.[57] "I do not want to ruin your life," he concluded, with a tone of finality, "and all that we might do to change the course of things would only bring a semblance of happiness. So I have come to accept the situation as it is and no longer seek to find some miracle solution. I am happy when I think of you."[58]

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 26-32.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[16] Naumann, "Marcel and Maria," p. 105. (Francis M. Naumann, "Marcel and Maria." Art in America, vol. 89, no. 4 (April 2001), pp. 99-110, 157.)

[17] See Ana Arruda Callado, Maria: Uma biografia (Rio de Janeiro: Gryphus; [Brasilia]: Ministério da Cultura; [Belo Horizonte], Minas Gerais: CEMIG and Governo do Estado, 2004), p. 56.

[18] Maria Martins, undated manuscript page, collection of Katia Mindlin Leite Barbosa, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, quoted in Francis M. Naumann, "'Don't Forget I Come from the Tropics': The Surrealist Sculpture of Maria Martins, 1940-1950," Maria: The Surrealist Sculpture, exh. cat. (New York: Andre Emmerich Gallery, 1998), pp. 22-23.

[19] Jacques Lipchitz, in "Conversations with Lipchitz," transcript of an unpublished interview conducted by Deborah A. Stott in Pietrasanta, Italy, 1968, p. 157, Tate Library and Archive, London, Hyman K. Reitman Research Centre. Between 1968 and 1970, Stott tape-recorded 185 hours of her conversations with Lipchitz, some of which were published in Stott, Jacques Lipchitz and Cubism (New York: Garland, 1978). However, the material relating to Martins remains unpublished. Although Lipchitz does not mention Martins's name in the interviews, the biographical details he discusses, combined with the use of titles such as Yara in his own works of this time, leave no doubt that he is referring to her. In Lipchitz's autobiography, he spoke of these works as having "a very close personal association, since they were related to someone with whom I was in love at that time. Most of them, thus, are made to express the sense of exaltation of the woman. They are works inspired by passion and I think they reflect this fact"; Lipchitz with H. H. Arnason, My Life in Sculpture (New York: Viking, 1972), p. 159.

[20] Maria Martins's emphasis in her work on native Brazilian culture, especially the myths and legends of the Amazon river, can be seen as part of a larger movement in Brazilian modern art in which artists and musicians explored the theory of antropofagia (cultural cannibalism) put forth by Osvaldo de Andrade in his 1928 Cannibal Manifesto. De Andrade used cannibalism as a metaphor for devouring and resisting what he perceived to be the pernicious influence of European colonial culture in South America. As literary historian Eduardo Subirats has argued, "Brazilian Anthropofagia transformed the fears and hatreds traditionally linked to European stories about American cannibalism into the artistic acknowledgement of a state of absolute freedom and a poetic vision of cultural renovation"; Subirats, "From Surrealism to Cannibalism," in Jorge Schwarz, ed., Da Antropofagia A Brasília: Brasil, 1920-1950, trans. Elizabeth Power et al., exh. cat. (São Paulo: Museu de Arte Brasileira, Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, and Cosac & Naify ; Valência: Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, 2002), p. 232. See also Carlos Basualdo, ed., Tropicália: A Revolution in Brazilian Culture, exh. cat. (Sao Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2005), p. 63. I am grateful to Carlos Basualdo for bringing the notion of antropofagia to my attention in regard to Martins's sculpture.

[21] Maria Martins, "Yara," in Amazonia by Maria, exh. cat. (New York: Valentine Gallery, 1943), unpaginated.

[22] Jacques Lipchitz, quoted in Stott, "Conversations with Lipchitz," p. 157.

[23] See C. Powell Minnigerode, "Sculptures by Maria Martins," Bulletin of the Pan American Union, vol. 75, no. 12 (December 1941), p. 684.

[24] This exhibition took place May 11-30, 1942, and included twenty-one works by Maria, four of which, including Yara, had recently been cast in bronze at John Spring's Modern Art Foundry in Long Island City; see Sculptures by Maria, exh. cat. (New York: Valentine Gallery, 1942).

[25] See the entry "Maria Martins, Yara," in Sculpture of a City: Philadelphia's Treasures in Bronze and Stone (New York: Fairmount Park Art Association and Walker Publishing, 1974), p.304.

[26] Henri Marceau, quoted in "From Brazil," Art Digest, vol. 17, no. 2 (October 15, 1942), p. 21.

[27] In his review of the artist's solo exhibition at the Valentine Gallery, Edward Alden Jewell declared that he would "be very much surprised to learn that Maria Martins had at no time felt the more or less direct influence of [Antoine] Bourdelle, as here, it would seem, exemplified by the ornate 'Nostalgia' and 'Yara,' as well as by the coyest of the Salomés"; Jewell, "A Project and Current Activities," New York Times, May 17, 1942, section 10, p. 5.

[28] Katia Canton, "Maria Martins: The Woman Has Lost Her Shadow," trans. Odile Cisneros, Núcleo histórico antropofagia e histórias de canibalismos, vol. 1, XXIV Bienal de São Paulo (São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 1998), p. 297.

[29] Maria Martins, "Cobra Grande," in Amazonia by Maria, unpaginated.

[30] Illus. in Alan G. Wilkinson, The Sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 2, The American Years, 1941-1973 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000), cat. 369.

[31] Shortly after the breakup of their relationship, Lipchitz created a tragic self-portrait entitled The Pilgrim, which depicts an eviscerated standing figure whose flayed skin and exposed entrails no doubt reflect his own raw emotions at the time. The sculptor later described this expressionistic figure as having a head "like an exploding bomb. He is disemboweled, with something like a snake entangled with a rose within his bowels"; Lipchitz with Arnason, My Life in Sculpture, p. 159. In 1971, just two years before his death, Lipchitz created his final image of Martins, whose voluptuous, nude body he recollected from memory in the bronze sculpture L'Amazone.

[32] Maria Martins, quoted in "Underground Art," Time, vol. 62, no. 18 (May 6, 1946), p. 64.

[33] Julien Levy, quoted in Anne d'Harnoncourt, "Visit to Julien Levy," February 24, 1973, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Marcel Duchamp Exhibition Records, Philadelphia Museum of Art, "Marcel Duchamp," Reference material, Interviews, box 13, folder 56.

[34] See Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp: The Box in a Valise, trans. David Britt (New York: Rizzoli, 1989), p. 282. The Boîte-en-valise is inscribed "pour Maria ce no. XII de vingt boîtes-en-valise contenant chacune 69 items et un original et par Marcel Duchamp New York 6 April 1946."

[35] Research to establish the exact nature of the medium used in Paysage fautif was carried out by the conservation department of the Menil Collection, which recently had borrowed the Boîte-en-valise containing the ejaculated landscape for the 1987 exhibition Marcel Duchamp: Fountain; ibid.

[36] See, for example, David Hopkins, "Questioning Dada's Potency: Picabia's 'La Sainte Vierge' and the Dialogue with Duchamp," Art History, vol. 15, no. 3 (September 1992), pp. 317-33. According to Hopkins, "the work wittily parodies the burgeoning aesthetic of Pollock" and "the painterly gesture as an index of masculinity"; ibid, p. 330.

[37] See Naumann, "Marcel and Maria," pp. 102-5. (Francis M. Naumann, "Marcel and Maria." Art in America, vol. 89, no. 4 (April 2001), pp. 99-110, 157.)

[38] The thirty-five letters that Duchamp sent to Maria Martins remained in the possession of her family until they were sold at auction at Sotheby's, Paris, May 30, 2006, lot 69.

[39] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins [c. 1946].

[40] Calvin Tomkins, for example, speaks of the "frank sensuality that kept breaking through in [Duchamp's] letters," while making no reference to the fact that the vast majority of the correspondence deals with mundane matters; Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (New York: Holt, 1996), p. 366.

[41] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, May 13 [1951?].

[42] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, July 17 [1948].

[43] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, October 12 [1948].

[44] See Lucia Brown, "Mme. Martins Still Chic, Fiery—and Charming," Washington Post, December 4, 1949, p. 25. This article, written after Martins and her family had moved to Paris following her husband's appointment as the Brazilian ambassador to France, emphasized her charm and personality, and her reputation as a popular and glamorous hostess during her time in Washington.

[45] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins [c. 1946].

[46] "Underground Art," Time, vol. 62, no. 18 (May 6, 1946), p. 64.

[47] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, April 7 [1949].

[48] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, May 24 [1949].

[49] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, June 6 [1949].

[50] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, June 20 [1949] (emphasis in the original).

[51] John Elderfield has supplied a detailed account of the contents of the Merzbau, which included a clutter of miniature objects nailed and collaged together, as well as items of a personal nature such as a bottle containing Schwitters's urine, in which everlasting flowers were floating, that hung to the left of the entrance; see Elderfield, Kurt Schwitters, exh. cat. (New York: Thames and Hudson for the Museum of Modern Art, 1985), pp. 144-71.

[52] Schwitters's own account of the Cathedral of Erotic Misery describes a hallucinatory arrangement of tiny fetish objects, often displayed in illuminated glass-fronted boxes that were concealed within the ribs and cavities of the wood and plaster grottos of the Merzbau and that included "the Sex-Crime Cavern with an abominably mutilated corpse of an unfortunate young girl, painted tomato-red, and splendid votive offerings"; ibid., p. 161. Other accounts suggest that Schwitters's bizarre and unsettling Sex-Crime Cavern was populated by a small plastic figure whose blood was rendered in red lipstick; ibid., p. 175. Duchamp's reaction to this macabre scene is unknown, but the site-specific Merzbau installation anticipates aspects of his own, slightly later environmental tableau.

[53] See Clare Carolin, "Outside In and Front to Back: Talking about the Weather from Beyond the Grave," in Richard Grayson, Carolin, and Roger Cardinal, eds. , A Secret Service: Art, Compulsion, Concealment, exh. cat. (London: Hayward Gallery, 2006), p. 31.

[54] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, March 19 [1950].

[55] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, February 12 [1951] (emphasis in the original).

[56] Ibid.

[57] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, October 25 [1951].

[58] Ibid.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES