Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Michael R. Taylor

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 2

CONSTRUCTION (Part 5)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 108-119, 126-127. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 ----

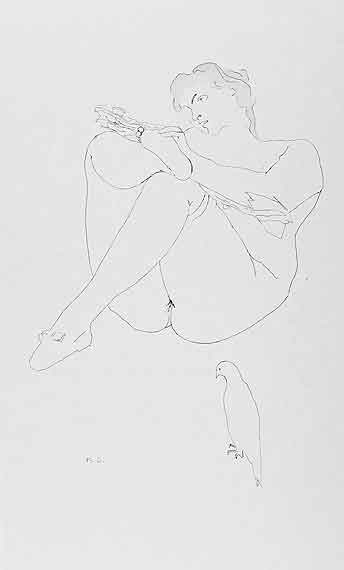

SELECTED DETAILS AFTER COURBET

Traces of the secret Étant donnés project also can be found in Duchamp's 1968 portfolio of erotic etchings based on amorous scenes from the art of the past.[192] The prints frequently make reference to his final work and its shared affinities with the sexual iconography and meaning of The Large Glass. In one instance, the faceless mannequin holding aloft the Bec Auer lamp in Étant donnés is shown with a dark-haired male figure, his hands clasped behind his head (FIG. 2a.54). This depiction of intimacy between a female nude and a male suitor creates an alternative, never-to-be-realized scenario for Duchamp's sculpture-construction. Repeating The Large Glass's theme of frustrated desire, Duchamp placed the physical barrier of the wooden door between the viewer and the recumbent figure to ensure that such a scene could take place only in the mind of the beholder.

FIG. 2a.54

Marcel Duchamp

Le Bec Auer, 1968

From The Large Glass and Related Works, with Nine Etchings by Marcel Duchamp

on the Theme of The Lovers, vol. 2 (Milan: Galleria Schwarz)

Etching and aquatint on paper

Plate: 34,6 × 23,3 cm (135⁄8× 93⁄16 inches), sheet: 42 × 25,5 cm (169⁄16 × 101⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mme Marcel Duchamp

Fig. 2.55

Gustave Courbet (French, 1819-1877)

Woman with White Stockings, 1864

Oil on canvas, 64,1 × 81,3 cm (251⁄4 × 32 inches)

The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania. BF 810, Gallery Vll

---- In another etching from the 1968 series, Duchamp appropriated the image of a seated nude from Gustave Courbet's painting Woman with White Stockings (1864; fig. 2.55), to which he added a rather nondescript bird, creating a delightful pun on faucon (falcon) — although the creature looks more like a lovebird than a bird of prey — a pun that also can be read as faux con, or "false cunt" (FIG. 2a.55). In 1962-63, Duchamp had used a similar play on words, possibly in reference to the artificial sex of the Étant donnés mannequin, when he turned the red- and-white French license plate for his Volkswagen car into a readymade after noticing the homophonic connection between Volkswagen and foux vagin, or "false vagina," a pun that he later commemorated in a poem (FIG. 2a.56).[193] However, it is the artist's deliberate allusion to Courbet's once-risqué painting of a woman putting on her stockings that deserves further consideration, since Duchamp discussed the nineteenth-century artist frequently and publicly after World War II.

FIG. 2a.55

Marcel Duchamp

Morceaux choisis d'après Courbet (Selected Details after Courbet), 1968

From The Large Glass and Related Works, with Nine Etchings by Marcel Duchamp

on the Theme of The Lovers, vol. 2 (Milan: Galleria Schwarz)

Plate: 34,4 × 23,2 cm (139⁄16 × 91⁄2 inches), sheet: 42 × 25,5 cm (169⁄16 × 101⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mme Marcel Duchamp

FIG. 2a.56

Marcel Duchamp

Faux vagin (False Vagina), 1962-63

Volkswagen license plate

10 × 45 cm (315⁄16 × 1711⁄16 inches)

Richard and Ellen Sandor Family Collection

---- In postwar interviews, Duchamp repeatedly condemned what he perceived to be Courbet's pernicious influence on modern art, which had placed special emphasis on the individual touch, or patte (literally, paw print), as the index of creative expression.[194] A highly ambitious, entrepreneurial artist seeking fame and fortune in Paris during the Second Empire, Courbet created a number of anodyne, market-driven paintings in which the pure visual pleasure of luscious surface textures made up for a paucity of new and radical ideas. His slickly painted female nudes similarly reveled in the sensuousness of oil paint, with which the artist, through consummate control of his medium, was able to create the illusion of voluptuous flesh — provoking scandals that gained him public notoriety through the press. In 1945, Duchamp had insisted that his own work and ideas were antithetical to Courbet's approach: "I was interested in making painting serve my purposes, and in getting away from the physicality of painting. For me Courbet had introduced the physical emphasis in the XIX century. I was interested in — ideas not merely in visual products. I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind."[195] According to Duchamp, the richly embellished surfaces of paintings by Courbet and his twentieth-century successors created art that appealed to the eye but not the brain, since they downplayed intellectual ideas in favor of the seductive slickness of the oil medium. In 1968, Duchamp explained that "everything since Courbet has been retinal ... you look at a painting for what you see, what comes on your retina, you see? You would add nothing intellectual about it."[196]

---- Duchamp connected Courbet's retinal revolution with the work of the Abstract Expressionists, whose paintings he abhorred. "Abstract Expressionism was not intellectual at all for me," he said in 1965, "it is under the yoke of the retinal. I see no gray matter there."[197] For Duchamp, this anti-intellectual, commercial approach to painting, in which an artist's personal style was more important than his ideas, also had its origins in Courbet's work, as he explained in 1959: "Courbet's revolution was mainly visual. He insisted, without even mentioning it, that a painting is to be looked at, and only looked at, and the reactions should be visual or retinal, not much to do with the brain. A plain physical reaction in front of a painting. This is still in vogue today, if I might say so. Expressionism is the line, the form, the play of colours together and the more abstract the better."[198] Several years later, Duchamp again outlined what he saw as the century-long trajectory of retinal art, beginning with Courbet and continuing in his own time through the gestural brushwork and tactile intensity of the Abstract Expressionists, such as Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Philip Guston, whose paintings "reached the apex of this retinal approach."[199]

---- Duchamp's disparaging evaluations of Courbet and retinal painting in the late 1950s and early 1960s were not shared by the Abstract Expressionists, many of whom admired the painterly facture of Courbet's landscapes, especially those in which the variegated palette-knife work takes on abstract qualities, as well as the physical energy of his frenzied paint application, which suggested to mid-twentieth-century viewers the power of nature. De Kooning, for example, praised Courbet in a 1958 interview in Art News. When he was posed the question "Is today's artist with or against the past?" he responded: "I'm very interested in Courbet. He could walk in a forest and see something, concretely, just the way it is; be obsessed by the bark on a tree. His painting is not tradition or nature or style, but there it is."[200] In the following year, the catalogue of a Courbet retrospective exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art explicitly connected his work with Abstract Expressionism in terms that echo Duchamp's contemporaneous pronouncements: "There is no real contradiction between Courbet's way of seeing things and that, of the Abstract Expressionists; instead, there is a progressive development from one to the other, almost a lineal descent, paradoxical as this may seem when judged superficially."[201] In 1960, Jackson Pollock's work was compared to that of the nineteenth-century French artist in an article that praised Courbet's "bravura and command in paint handling"[202] as an important precursor to the pure abstractions of the contemporary painter's "poured" paintings, as well as to "the rugged frontality of de Kooning and Kline."[203] Duchamp's numerous remarks about Courbet and Abstract Expressionism between 1945 and his death in 1968 provide a broader context in which to understand his appropriation of the nineteenth-century painter's erotic works in the 1968 series of etchings, as well as the retinal aspect of Étant donnés. In fact, Duchamp's final project may be seen as deconstructing Western regimes of representation through a demonstrably staged and artificial recapitulation of the modes and practices of modern painting since Courbet.

---- Duchamp had ample opportunity to see and study Courbet's Woman with White Stockings, which since 1926 had been in the collection of Dr. Albert C. Barnes in Merion, on the outskirts of Philadelphia.[204] Duchamp first visited the Barnes Foundation in 1933 and may have returned in the early 1950s while working on installation plans for the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[205] During these visits, his attention undoubtedly would have been drawn to the explicit sexuality of the work, as well as its incongruous hanging by Dr. Barnes at his foundation, where it was sandwiched between a small still life with flowers by Auguste Renoir and an eighteenth-century Pennsylvania German dower chest (see fig. 2.56). This unusual, pyramid-shaped configuration could be read as the form of a human body, with the dower chest representing the legs and the Renoir flower piece the upper torso, and the apex comprising another small Renoir study of a woman's head and a wrought-iron Pennsylvania German latch in the shape of a tulip.[206] Within this anthropomorphic installation, Courbet's nude functioned as the lower half of the body and focused the viewer's attention on the female genitalia, in much the same way as Duchamp's peepshow tableau. According to the artist's stepdaughter, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, Duchamp met with Dr. Barnes on one of his visits to the foundation and, pointing to Woman with White Stockings, told him that he would "use this painting in my own work one day."[207]

Fig. 2.56

Installation of Courbet's painting Woman with White Stockings

at the Barnes Foundation, Gallery VII, east wall.

---- Courbet's painting depicts a young woman seated on the ground, suggestively pulling a stocking over her right foot, an ambiguous pose that leaves the viewer unsure of the exact nature of the scene. Is the woman a prostitute or a rustic maid? Is she dressing or undressing? Are we witnessing the aftermath of sexual intercourse or a swim in the nearby body of water? Stripping away all extraneous details, Duchamp's etching (FIG. 2a.54) hones in on the figure's exposed genitals, declaring Courbet's lewd intentions in his seemingly innocent scene of a woman in a landscape setting. The addition of the bird, with a play on words that underlines the artifice and illusion of the painted scene, recalls other works by Courbet, such as Woman with a Parrot (1866), in which a parrot — a common metaphor of male sexuality in nineteenth- century French painting — alights on the outstretched hand of a flame-haired, buxom nude sprawled on her back across a four-poster bed (fig. 2.57).[208]

Fig. 2.57

Gustave Courbet

Woman with a Parrot, 1866

Oil on canvas, 129,5 × 195,6 cm (51 × 77 inches)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer

---- As art historian Michael Fried has observed, this vivid-hued, blue-fronted parrot (Amazona aestiva) is "a 'phallic' creature whose outspread wings and tail in effect mirror the woman's outward-streaming hair."[209] As a phallic symbol, the bird offers a visible anchorage from which the male viewer/voyeur can survey and dominate the submissively reclining odalisque, whose status as a harem woman is signified through the exotic origins of her dazzling feathered companion.[210] Duchamp no doubt was familiar with this notorious painting, in which plump, juicy flesh was juxtaposed with the shimmering multicolored plumage of the Amazonian bird, as the work had been on almost continuous display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York since its acquisition in 1929.

---- Duchamp's interest in decoding and deconstructing the veiled eroticism of Courbet's representations of the female nude has important ramifications for Étant donnés, suggesting a possible link between the staging of scopophilic pleasure and his critique of retinal painting after Courbet. Duchamp's comments on the nineteenth-century artist, when taken in conjunction with the appropriation of his imagery, suggest that Duchamp equated the libidinous wantonness of Courbet's reclining women and their pet birds with the luscious painted textures of his canvases, which revel in the sensuous, slick. and tactile quality of oil paint with hedonistic abandonment similar to that of the nudes who willfully flaunt their sexuality.

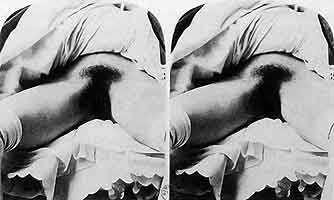

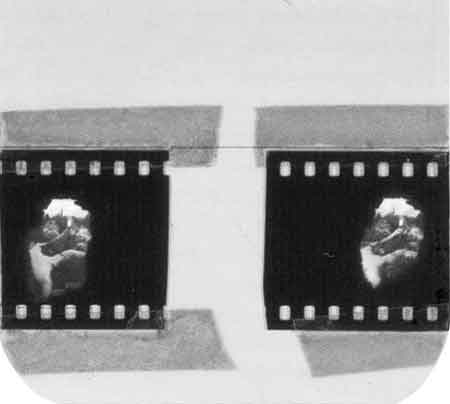

---- Duchamp's preoccupation with Courbet also suggests that Étant donnés may have been in part a response to Courbet's sumptuous painting of a cropped female torso entitled L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World), which was made for the Turkish-Egyptian diplomat, art collector, and bon vivant Khalil Bey (fig. 2.58). Painted in 1866, this erotic work consists of a close-up view of a supine woman with legs spread, depicted in extreme foreshortening from her thighs to her breasts, and partially covered by a white sheet. Unlike the depilated vulvalike orifice of the female nude in Duchamp's tableau, Courbet paid especially close attention to his female model's thatch of black pubic hair and tightly clamped labia majora, with the faintest suggestion of a clitoris, all of which he carefully delineated with exacting realism. Scholars recently have connected Courbet's nudes with the immediate, voyeuristic eroticism of high-quality stereographic images of the genitalia of anonymous female models that were made by contemporaries such as Auguste Belloc (fig. 2.59) and Alexis-Louis-Charles Gouin.[211] Duchamp, of course, had a lifelong interest in optical devices and stereoscopic and anaglyphic images, and during the 1960s he made a large number of stereographic photographs of Étant donnés in what proved to be a futile effort to capture accurately its three-dimensionality (see FIG. 2b.5).[212] Like the tableau-diorama seen through the two small oblique holes placed at eye level in the rustic door, stereoscopy was based on binocular rather than monocular vision and thus offered Duchamp a far stronger visual illusion than could be obtained through conventional "retinal" oil painting. As art historian Jean Clair has observed, through its excessive grounding in the sensory world, "the stereoscopic image showed the way to a purely ideal configuration, the intelligible result of a synthesis certainly closer to the brain — and to the working of a cosa mentale — than to the retinal effect."[213]

Fig. 2.58

Gustave Courbet

L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World), 1866

Oil on canvas, 46 × 55 cm (181⁄8 × 215⁄8 inches)

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Fig. 2.59

Auguste Belloc (French, 1800-1867)

Photographs for the stereoscope, mid-nineteenth century

FIG. 2b.5

Marcel Duchamp

Stereoscopic photographs of Étant donnés, from the Dom Perignon Box, c. 1965

---- It is intriguing to consider whether Duchamp had the opportunity to see firsthand Courbet's Origin of the World while working on his own shockingly erotic final masterwork. Several scholars have pointed out the stunning visual similarities between Courbet's close-up depiction of the splayed lower section of a woman's body and the exposed genitalia on display in Étant donnés.[214] Until 1955, when The Origin of the World was purchased for 1,500,000 francs by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and his wife, Sylvia Bataille Lacan, the work had been hidden from view.[215] Before the painting resurfaced at auction in 1955, it was known only through nineteenth-century written accounts and caricatures, including a cartoon by Léonce Petit that appeared in 1867 in the satirical magazine Le Hanneton (fig. 2.60). The painting was not published until 1967, when a hand-tinted, full-color reproduction appeared in Gérard Zwang's sexual encyclopedia Le Sexe de la femme.[216]

Fig. 2.60

Léonce Petit (French, 1839-1884)

G. Courbet on the cover of Le Hanneton, June 13, 1867

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

---- Timed to coincide with Courbet's retrospective at the Rond-point de l'Alma in Paris, just outside the grounds of the Exposition Universelle, Petit's caricature depicts the artist standing in front of a display of his own works, holding a beer glass in one hand and a palette in the other. Among the works rendered by Petit is The Origin of the World, reduced to a single vibrant but crudely rendered fig leaf on a white ground; the fig leaf, of course, offers an intriguing link between Courbet's legendary painting and the erotic objects associated with the production of Étant donnés. Duchamp may not have been aware of the cartoon's original publication history, but he would have known Camille Pissarro's Portrait of Paul Cezanne (1874; fig. 2.61), where Petit's satirical print is shown pinned to the wall behind the bearded painter — with special emphasis placed on the solitary fig leaf, which stands in for Courbet's tableau of illicit looking in the same way that Duchamp's synecdochical Female Fig Leaf represented the secret Étant donnés project in the 1950s and 1960s.

Fig. 2.61

Camille Pissarro (French, 1830-1903)

Portrait of Paul Cézanne, 1874

Oil on canvas, 73 × 59,7 cm (283⁄4 × 231⁄2½ inches)

National Gallery, London. On loan from Graff Diamonds Ltd.

---- Duchamp probably saw The Origin of the World in late September 1958, when he and Teeny were invited to dine with the Lacans at their apartment at 3 rue de Lille in Paris.[217] His friendship with Sylvia Lacan, the former wife of the Surrealist writer Georges Bataille, surely helped him to gain access to the work, whose existence was common knowledge among the Surrealists in the 1950s. The tantalizing connections between the viewer/voyeur schema of Duchamp's diorama and Lacan's psychoanalytical ideas on the gaze, especially relating to what art historian Hal Foster has described as the "troublesome connection between perspective and castration," gain credence with the knowledge of this meeting.[218] Lacan would not publish his seminars on the gaze until 1972, although he had been teaching and thinking about the subject since the 1950s. By this time, Duchamp had completed the nude and her bed or bier of branches and leaves, but his interest in the eroticization of vision offers fascinating parallels with Lacan's psychoanalytic theories.

---- The artist thus joined a long list of distinguished visitors who saw Courbet's painting after the Lacans acquired it, including Marguerite Duras, Michel Leiris, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Dora Maar. A former patient of Jacques Lacan following her painful breakup with Picasso, Maar saw The Origin of the World at La Prévôté, the Lacans' country house in the village of Guitrancourt near Mantes-la-Jolie, in the company of the American art historian and biographer James Lord, who provided a colorful account of seeing the painting in his memoirs of Picasso and Maar. After lunch, Lord recalled, Jacques Lacan promised to show them "something extraordinary" in his studio, where he unveiled "a detailed and very beautifully painted close-up study of the genitalia of a fleshy, almost corpulent female."[219]

---- Duchamp had completed the Étant donnés mannequin by the late 1950s, but he continued to work on the painted backdrop and had yet to procure the wooden door through which his astonishing mise-en-scène was to be witnessed. When he saw The Origin of the World at the Lacans' home, it was concealed beneath a painted wooden panel that had been made in 1955 by the Surrealist artist Andre Masson. A secret mechanism allowed Masson's panel to be slid open, revealing Courbet's recently rediscovered painting underneath.[220] Starting with its first owner, Khalil Bey, who hid the work behind a green veil in his private dressing room, The Origin of the World had always been placed behind some kind of covering that prevented immediate access to the taboo image of exposed female genitalia. When Edmond de Goncourt saw the work at the gallery of Antoine de la Narde in 1889, it was concealed behind a second Courbet painting that the French art critic described as a work on panel depicting a village church in the snow.[221] This work was undoubtedly Le Château de Blonay (c. 1875; see fig. 2.62), an innocuous winter landscape featuring a castle that the dealer had housed in a false-bottomed frame within a locked tabernacle or cabinet, which when opened revealed Courbet's erotic masterpiece below. The unremarkable landscape hangs today in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, having been removed by another owner of The Origin of the World, the Hungarian-Jewish art collector Baron Ferenc Hatvany, who sold the covering panel to his brother-in-law, Baron Mór Lipót Herzog, who in turn donated the work to the museum in 1959.[222]

Fig. 2.62

Gustave Courbet

Le Château de Blonay, c. 1875

Oil on canvas, 50 × 60 cm (1911⁄16 × 235⁄8 inches)

Szépmũvészeti Múzeüm, Budapest

---- No doubt inspired by this former landscape cover, Sylvia Lacan commissioned André Masson, her brother-in- law, to create a similar painting on a sliding panel that would cover the work.[223] The subterfuge was essential, she said, since the neighbors and the cleaning lady "would not understand,"[224] but it also allowed the Lacans to slide open Masson's peek-a-boo panel at any time and theatrically divulge Courbet's painting to the startled surprise of visitors. Surrounded by a heavy gilt frame, Masson's painting fused wispy cloudlike forms and other sky and landscape elements with details taken from Courbet's truncated female torso and open thighs in a diaphanous, seemingly abstract image that both concealed and alluded to the hidden scene underneath (see fig. 2.63). Like the composite heads of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, in which the human form is made up of an accretion of disparate elements, Masson's Terre érotique (Erotic Landscape) is a double image, whose rapid tracery of delicate white brushstrokes on a reddish brown ground can be read both as a reprise of Courbet's prone and nude figure, and as a landscape with rolling hills, crevices, and freely rendered trees and bushes. Indeed, the oscillating relationship between figure and ground in Masson's composite image is so powerful that the recumbent nude is transformed into a landscape to be entered and exited through the vagina, in the form of a grotto or ravine fringed with pubic hair resembling undergrowth.

Fig. 2.63

André Masson (French, 1896-1987)

Terre érotique (Erotic Landscape), 1955

Oil on wood panel, 46 × 55 cm (181⁄8 × 215⁄8 inches)

Private collection

---- Masson's panel painting referenced Courbet's sexualized Franche-Comté landscapes, such as the suite of paintings made about 1864 entitled The Source of the Loue, in which the rock formations of the cave entry to the gushing water grotto evoke vaginal openings or womblike enclosures (see fig. 2.64). In the 1930s, Masson had utilized this "woman as nature" analogy in a similar drawing of a mountainous landscape, rendered with an intricate filigree of fine lines, in which a man enters the gaping tunnel of a grotto-vagina whose entrance suggests that the landscape presents the body of a woman available for imaginative penetration. An article by Masson that was published in the Paris-based arts magazine Critique[225] may have persuaded the Laecns to commission the Surrealist artist to create the panel cover four years later, in 1955. That same year, Masson also painted his own version of Courbet's The Source of the Loue, as well as numerous erotic drawings that relate directly to the nineteenth-century French artist's nudes. It thus appears than in the panel painting Masson returned to his earlier interest in the morphological resemblance between Courbet's depictions of caves and rock formations and his overtly erotic female nudes, several' decades before the possible connections between the two genres in the nineteenth-century painter's work were discussed by art historians.[226] The waterfall in Étant donnés similarly evokes the notion of woman as nature seen in Courbet's paintings of the Loue River, in which the landscape stands in for the absent female body.[227] As Duchamp no doubt was aware, Courbet spent the last four years of his life in exile at La Tour-de-Peilz, situated just a few miles from Bellevue, the source of Duchamp's backdrop.

Fig. 2.64

Gustave Courbet

La Source de la Loue (The Source of the Loue), 1864

Oil on canvas, 99,7 × 142,2 cm (391⁄4 × 56 inches)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer

---- An important aspect of the landscape backdrop was the kinetic waterfall mechanism, which added a piquant note of movement to the otherwise eerily still grotto. Its shifting illumination was produced by a light fixture housed in a five-pound Peek Frean's cookie tin. The waterfall consists of a translucent molded piece of hardened glue that covers a hole cut through the wooden support of the landscape backdrop. Behind the backdrop, a rotating perforated aluminum disk, activated by a small motor, revolves in front of the lightbulb to create the illusion of a twinkling waterfall as it shines through the glue-covered hole. The previously un-discussed name of the cookie tin — Peek Frean, the British biscuit manufacturer — underlines Duchamp's sense of humor and love of wordplay in its allusion to the voyeurs who peek through the peepholes at the waterfall but never see the concealed biscuit tin housing the throbbing, slow-speed motor that drives it.

---- Duchamp apparently experimented with a number of motors to power the artificial waterfall before finding a satisfactory solution, as he gave several unused examples to his stepson Paul Matisse.[228] An invoice discovered among Duchamp's belongings in his Eleventh Street studio identifies the electrically powered motor as the Brevel Worm Motor, Standard Series W, purchased by the artist for $8.50 from the Brevel Products Corporation in Carlstadt, New Jersey, which shipped the WA3L1-620b-84 motor to his home on 28 West Tenth Street on December 30, 1963. According to the company's advertisement, this "compact, well engineered gear head motor" was designed specifically for "applications requiring exceptionally quiet, smooth running, slow speed operation and highest quality performance" (fig. 2.65). The promise of a low-cost, dependable motor, which purred softly while turning the waterfall mechanism like a rotisserie chicken, was perfect for the artist's needs. The motor is slightly slower today, turning at a speed closer to 2½ rpm than to the 3 rpm specified by Duchamp in his comprehensive Manual of Instructions for the assembly of Étant donnés, but otherwise it has proved to be a good investment, and has operated almost continuously and trouble free since its installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 2.65

Advertisement for Brevel Worm Motor

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d'Harnoncourt Records

---- The invoice from Brevel confirms that the waterfall mechanism was one of the final elements of Étant donnés that Duchamp worked on, along with the complex lighting system, which also dates to between 1962 and 1964. Receipts for the electrical wires, high-wattage lamps, 150-watt lightbulbs (Century Lights), and fluorescent tubes reveal that he arranged for most of this equipment to be shipped to his home address at 28 West Tenth Street, possibly to avoid suspicion about the purpose of the fixtures. The dates of the receipts indicate that Duchamp began the expensive and difficult task of lighting the mannequin and her landscape environment in 1962 — spending more than fifty dollars on lighting equipment in November of that year alone — and also allow us to identify the fixtures, such as three overhead 150-watt Project-O-Lite picture spots. This state-of-the-art equipment included an Alzak reflector, an optical lens system, and built-in four-way shutters for accurate beam control. The museum-standard light projectors were used by the artist to illuminate the painted collage backdrop, since they could be tilted and aimed with great precision; they are clearly visible in the Manual of Instructions. Duchamp purchased most of his lighting materials from Century Lighting at 521 West Forty-third Street, with some items coming from Arco Lighting, located on the second floor at 1010 Third Avenue. The last known invoice from Century Lighting, which charged the artist $54.29 on October 22, 1964, suggests that the convoluted electrical and lighting system was completed at that time.

---- According to Teeny Duchamp, the idea for the inner brick wall — with its jagged aperture framing the view from the bifocal peepholes — occurred to Duchamp after she became romantically involved with him in the early 1950s, and was not part of his original conception for the tableau-construction. The bricks for this broken threshold were collected from demolition sites near his Fourteenth Street studio, apparently as late as the 1960s, since Teeny remembered Duchamp filching them from the construction site for a new Brentano's bookstore on Eighth Street.[229] The weathered exterior door for his luminous tableau-construction — which, like Masson's sliding panel for The Origin of the World, physically separated the viewer from the forbidden scene inside — was al so incorporated in Étant donnés by the mid-1960s, sinceit appears in the Polaroid photographs that were taken by Ducham p in the fall of 1965 for the first Manual of Instructions. Of course, Duchamp would have seen Masson's painting at the Lacans in the late 1950s, around the time that he was working on the landscape backdrop and devising his own viewing system for the tableau-construction. The rickety, weather-beaten wooden door was actually part of a much larger farmhouse door leading into a courtyard that the artist had found after a considerable search in La Bisbal, in the Empordà district of Catalunya (figs. 2.66 and 2.67a,b). Having rejected several other doors, Duchamp and Teeny were delighted to learn that the owner of the door they had finally selected was planning to replace it, and thus was ready to sell it at a reasonable price.[230]

Fig. 2.66

Marcel Duchamp

Exterior door of Étant donnés in its original setting,

with Teeny Duchamp, La Bisbal, early 1960s

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 2.67a,b

Marcel Duchamp

Photographs of additional doors in La Bisbal, early 1960s

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- Ancient wooden doors of this type were a familiar sight in the region until the 1960s, and the British artist Richard Hamilton, who spent his summer vacations in Cadaqués at the same time as Duchamp, confirmed that such doors "often give on to a ruined interior and offer glimpses of secret landscapes almost as phantasmagorical as the one which Duchamp conceived for himself."[231] Duchamp shipped the door to New York, where he cut it down into four separate sections and bolted each to a second, inner door of commercial panel construction.[232] A crossbar made of wooden planks was nailed into the exterior door with heavy spikes to cover the places where the panels joined; planks and caulk sealant also concealed the opening between the inner door and the surrounding brick archway. The double thickness of the recycled door helped to stabilize the ancient exterior, which had splintered and eroded in places, having long been exposed to the elements and worn down through constant use. Duchamp also may have added the second, inner door to ensure that the rickety Spanish portal was sturdy enough to handle the continual weight of viewers pressing against it.

---- To prevent shafts of light from escaping through the cracks in the old door, Duchamp covered the back of the inner door with four pieces of black velvet, a material he had used earlier for the Please Touch cover of the 1947 Surrealist exhibition catalogue (FIG. 2a.17 - Part 1). The lining, placed between the door and the interior brick aperture, inescapably recalls the optical devices of early photography — in which the photographer stands under a black cloth to construct a single view through the lens for the spectator — as well as the cinema, where the viewer peers through a dark space at a brightly illuminated projected image. In the Manual of Instructions, Duchamp also compared the effect of the black velvet curtains to "a kind of completely dark camera obscura when looking through the voyeur's peepholes."[233]

---- In the artist's studio, the four panels that make up the door were hung on a steel bar (replaced with an aluminum track at the Philadelphia Museum of Art) that allowed Duchamp to slide the individual panels laterally in order to photograph the work from different angles; this was an important consideration when the artist was assembling the Manual of Instructions, since he wished to convey the exact placement of every element to future custodians of the work, knowing that the slightest margin of error would destroy the illusion he had devised so carefully. The stretch of internally illuminated blue sky above the hilly landscape, for example, bears a white X that Duchamp placed to demarcate the uppermost parameter of vision from the eyeholes. The mark can be observed by those curious visitors who bend down and peer upward, but the vast majority of viewers look straight ahead and never know it is there, as Duchamp's precise instructions ensured that the X would not be obvious when the piece was reassembled in Philadelphia.

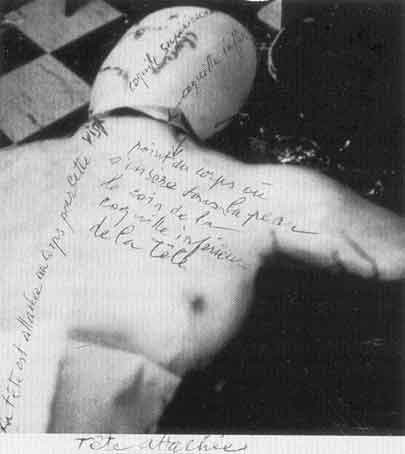

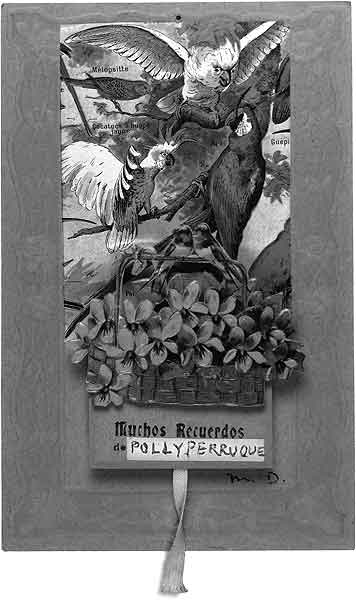

---- Duchamp completed Étant donnés in his Eleventh Street studio, to which he had moved on January 1, 1966. His final additions to the environmental tableau-construction were probably the tufts of dirty-blonde underarm hair and the blonde wig that replaced the nude's earlier chestnut-brown hairpiece shortly after the artist moved into his new studio. This curled wig, which covers the figure's head — constructed from two separate pieces of curved, opaque plastic held together by a clothespin (see FIG. 2b.6) — signals the shift in Duchamp's affections from the brunette Maria Martins to the blonde Teeny. The artist had sported a wavy blonde wig in a comical Polaroid taken by Man Ray in the mid-1950s, reprising Duchamp's earlier Rrose Sélavy gesture and perhaps suggesting that this homage to Teeny had been on his mind for some time (fig. 2.68). In 1967, Duchamp made a humorous reference to the mannequin's wig when he added images of birds to a greeting card in Spanish representing a colorful landscape filled with trees and a basket of flowers, and signed and titled it Pollyperruque (FIG. 2a.57). This assisted readymade — created for the exhibition Polly Imagists at the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York, which opened on December 5, 1967 — contained references to both the wig (perruque in French) and the parrot in Courbet's famous painting. Duchamp found the old fashioned postcard in Cadaqués, to which he affixed a color plate from the Larousse encyclopedia — of a macaw, two varieties of cockatoo, and a budgerigar — and completed the card's greeting of "Muchos Recuerdos de ... "(Many recollections from ... ) by adding the name "Pollyperruque." The work thus combines two allusions to the secret Étant donnés project, namely, the mannequin's wig and the voyeuristic onlooker, signified by the exotic macaw or parrot that supplied the first half of the tide, as in "Polly wants a cracker," for the readymade.

FIG. 2b.6

Marcel Duchamp

Polaroid photograph of the head of the Étant donnés mannequin,

from the Manual of Instructions, 1966

Fig. 2.68

Man Ray

MarceI Duchamp in a blond wig, c. 1955

Polaroid photograph, 7,9 × 6,4 cm (31⁄8 × 21⁄2 inches)

Private collection

FIG. 2a.57

Marcel Duchamp

Pollyperruque, 1967

Readymade: collage on color-printed greeting card

14 × 8,9 cm (51⁄2 × 31⁄2 inches)

Graphische Sammlung, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

---- It was also in his new studio that he signed and dated the mannequin's truncated right arm (FIG. 2b.7), which is invisible from the viewer/voyeur's vantage point: "Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° Ie gaz d'éclairage / Marcel Duchamp / 1946-1966."[234] In the summer of 1968, while on his annual vacation in Spain, Duchamp selected the bricks to frame the four-panel door of Étant donnés and ordered them to be sent to his New York studio by Emilio Puignau, the main builder in Cadaqués. These would replace the three linoleum sections containing an imitation brick pattern that had served as a temporary placeholder for the archway. According to Teeny Duchamp, the artist himself intended to carry out the permanent installation of the tableau-construction at the Museum,[235] but did not live long enough to complete the last element of the work, the brick archway that frames the rustic wooden door. In the early morning of October 2, 1968, Duchamp died, with wath Teeny described as "the most calm, pleased expression on his face."[236]

FIG. 2b.7

Denise Browne Hare

Étant donnés in the Eleventh Street Studio

A Photographic Portfolio by Denise Browne Hare, 1968

The photographer Denise Browne Hare documented Étant donnés as it appeared in Duchamp's studio on East Eleventh Street in a series of twenty-seven black-and-white photographs that were taken during the last week of December 1968. This portfolio, which is published here in its entirety for the first time, was commissioned by the photographer's close friend, Alexina "Teeny" Duchamp, who felt it was important to capture for posterity the ambience of the artist's cramped and sparsely furnished studio. Like Duchamp's own images in the Manual of Instructions, Browne Hare's evocative photographs offer new insights into the hidden mechanisms of Étant donnés, including its eccentric lighting system, as well as the artist's dexterity in creating a nearly flawless visual illusion in the finished diorama. According to her recollection, the scene beyond the two peepholes was "indescribable," although the photographs she took would provide eloquent testimony to the work's arresting visual power and poetic mystery.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 ----

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 108-119, 126-127. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[192] For an excellent discussion of the Morceaux choisis etchings, see Hellmut Wohl, "Duchamp's Etchings of the Large Glass and The Lovers," in Kuenzli and Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, pp. 168-83.

[193] "Do you believe that/Rrose Sélavy said/VoIkswagen—faux vagin/Who knows who knows?/It's true it is our/plaque d'immatriCULation"; see Teeny Duchamp, "A Marcel Duchamp Readymade," in Hill, Duchamp, Passim, p. 176. Duchamp's final line appears to make reference to the Étant donnés mannequin's artificial cul, or ass.

[194] As Duchamp later explained to Calvin Tomkins: "There was never any essential satisfaction for me in painting. I just wanted to react against what the others were doing — Matisse and the rest. All that work of the hand. In French, there is an old expression, ‘la patte,’ meaning the artist's touch, his personal style, his ‘paw.’ I wanted to get away from ‘la patte,’ and from all that retinal painting"; Marcel Duchamp quoted in Tomkins, "Not Seen and/or Less Seen," New Yorker, vol. 40, no. 51 (February 6, 1965), p. 48.

[195] Marcel Duchamp. quoted in James Johnson Sweeney, "Eleven Europeans in America," Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, vol. 13, nos. 4-5 (1946), p. 20.

[196] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in "BBC Interview with Marcel Duchamp," in Francis M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Ghent, Belgium: Ludion, 1999), p. 300.

[197] Marcel Duchamp quoted in "Pop's Dada," Time, vol. 85, no. 6 (February 5, 1965), p. 85.

[198] Marcel Duchamp, interview with George Heard Hamilton, BBC Radio, January 19, 1959; repr. in "Mr. Duchamp, If You'd Only Known Jeff Koons Was Coming," Art Newspaper, February 1992, p. 13.

[199] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Katherine Kuh, "Marcel Duchamp." in The Artist Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), p. 89.

[200] Willem de Kooning, quoted in Thomas B. Hess, "Is Today's Artist with or against the Past?" Art News (New York). vol. 57, no. 4 (Summer 1958), p. 56. Duchamp no doubt was aware of de Kooning's remarks on Courbet, since they were preceded by a negative comment about L.H.O.O.Q., the artist’s 1919 rectified readymade, in which he altered and transformed a cheap chromolithograph of Leonardo's Mona Lisa through the addition in pencil of an upturned mustache and rakish goatee. De Kooning viewed this iconoclastic gesture as exemplary of the fact that "Marcel Duchamp's just not an art lover"; ibid., p. 27.

[201] René Huyghe, "Courbet," trans. Esther Rowland CIiford, in Gustave Courbet, 1819-1877, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1959), unpaginated.

[202] J. P. Sedgwick "The Artists’ Artist," Art News (New York), vol. 58, no. 9 (January 1960), p. 41.

[203] Ibid., p. 66. The possible connections between Courbet’s work and de Kooning's recent gestural abstractions were underlined in the layout of the opening spread of Sedgwick's article, which sandwiched the slashing diagonals of de Kooning's Ruth’s Zowie (1959) between two Courbet paintings — Young Girl with Seagulls (1865) and Deer in Covert by the Stream of Plaisir-Fontaine, Doubs (1866) — to underline their shared interest in strident color, implied structure, and pictorial rhythm; ibid., pp. 40-41.

[204] Albert C. Barnes purchased Courbet's Woman with White Stocking for $6,500 from the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris on July 6, 1926. The invoice listed the painting simply as "nu"; see Galerie Barbazanges, invoice to Albert C. Barnes, July 6, 1926, The Barnes Foundation Archives, Merion, PA, Presidents' flies, Albert C. Barnes correspondence, reprinted with permission.

[205] On November 29,1933, Duchamp wrote to Barnes requesting a visit to the Barnes Foundation, during which he hoped to persuade the American collector to purchase a Constantin Brancusi sculpture from an exhibition of the Romanian-born artist's work that he recently had organized for the Brummer Gallery in New York; Marcel Duchamp, letter to Albert C. Barnes, November 29, 1933, The Barnes Foundation Archives, Merion, PA, Presidents' files, Albert C. Barnes correspondence, reprinted with permission. Barnes agreed to meet Duchamp on December 3, 1933, and suggested that the artist take a train to North Philadelphia Station, where he would be waiting in a car that would take them to the foundation; see Albert C. Barnes, letter to Marcel Duchamp, December 1, 1933, The Barnes Foundation Archives, Merion, PA, Presidents' files, Albert C. Barnes correspondence, reprinted with permission. After the visit, Duchamp reported that Barnes was "very kind," but the artist feared the worst about the potential sale of the Brancusi (which in the end did not transpire) and added the coda that he was "not sure just how far his kindness [would] go"; Caumont and Gough-Cooper, entry for December 3, 1933, Ephemrrides.

[206] See Violette de Mazia, The Barnes Foundation: The Display of Its Art Collection (Merion Station, PA: The Barnes Foundation Press, 1988), p. 6.

[207] Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, interview with the author, Villiers-sous-Grez, March 30, 2007.

[208] As Richard Verdi has argued, exotic-looking pet parrots played the unsolicited role of surrogate male lovers in a succession of French nineteenth-century paintings, from Eugène Delacroix’s celebrated Woman with a Parrot (1827) to Courbet's provocative painting of the same title in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in which the reclining female nude, posed brazenly on a couch in the artist's studio, playfully holds her parrot-companion, whose "wings are outspread as though in eager anticipation of even more intimate contact with its mistress"; Verdi, The Parrot in Art: From Dürer to Elizabeth Butterworth (Birmingham, UK: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, and Scala, 2007), p. 29.

[209] Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 205.

[210] See Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), p. 134.

[211] Dominique de Font-Réaulx has suggested that Courbet had Belloc's lewd stereoscopic images of women's genitals "in his mind's eye" when he painted The Origin of the World. We know from Courbet's correspondence that he collected photographs of nude women, and among the few that have come down to us, a number in visiting-card format can be attributed to Belloc; see de Font- Réaulx, "Auguste Belloc: Obscene Photographs for the Stereoscope," in Gustave Courbet, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2008), p. 384.

[212] For more on the history of the stereoscope, see Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990).

[213] Jean Clair, "Opticeries," October, no. 5 (Summer 1978), p. 104.

[214] See, for example, Linda Nochlin's entry on The Origin of the World in Sarah Faunce and Nochlin, eds., Courbet Reconsidered, exh. cat. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), p. 178. Juan Antonio Ramirez has also connected The Origin of the World with Duchamp's final piece, arguing that Courbet's reclining female nude reveals her genitals in surprisingly close proximity to the observer; a daring foregrounding that "cuts her body" and prevents us from seeing her head and extremities, leading him to conclude that "it is more than likely that Duchamp had this picture in mind when he produced Étant donnés"; sec Ramírez, Duchamp: Love and Death, Even, trans. Alexander R. Tulloch (London: Reaktion, 1998), p. 239.

[215] See Thierry Savatier, L'Origine du monde: Histoire d'un tableau de Gustave Courbet (Paris: Bartillat, 2006), p. 145. Savatier's exhaustive study offers the most comprehensive account of the painting's complicated provenance and its historical reception.

[216] See Gérard Zwang, Le Sexe de la femme (Paris: La Jeune Parque, 1967). For a detailed analysis of the publication history of Courbet's painting, see Linda Nochlin, "Courbet's L'Origine du monde: The Origin without an Original," October, no. 37 (Summer 1986), pp. 76-86.

[217] Although the exact date of this encounter is unknown, two photographs of Duchamp, Lacan, and their friends at a dinner party hosted by Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning in Paris on September 30, 1958, suggest that the meeting took place around this time. These photographs were reproduced in Paul B. Franklin, "'2 Mots de joie à recevoìr ta lettre': Les Lettres de Marcel Duchamp à Patrick Waldberg," Étant donné Marcel Duchamp, no. 7 (2006), pp. 202-3. Thierry Savatier finds it inconceivable, given Lacan's deep admiration for Duchamp, that he would not have brought the painting to Paris for this important rendezvous; see Savatier, L’Origine du monde, p.162.

[218] Hal Foster, Prosthetic Gods, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), p. 275. As Foster points out, the viewer of Étant donnés, "positioned as a Peeping Tom, looks through a perspectival construction at the splayed body of a female nude, directly at her vulva: viewing point and vanishing point coincide at the point of putative lack or castration. ... This is the double bind of the Lacanian viewer as well: apparent master of vision yet potential victim of the gaze."

[219] James Lord, Picasso and Dora: A Personal Memoir (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1993), pp. 203-4.

[220] See Elisabeth Roudinesco, Historie de la psychonalyse en France, vol. 2 (Paris: Fayard, 1994), p. 305.

[221] See Edmond et Jules de Goncourt, Journal: Mémoires de la vie littéraire, 1889-1890, vol. 16 (Monaco: L'lmprimerie Nationale, 1956), p. 97 (entry for June 29, 1889).

[222] See Konstantin Akinsha, "The Mysterious Journey of an Erotic Masterpiece," Art News (New York), vol. 107, no. 2 (February 2008), p. 94.

[223] André Masson was married to Sylvia's sister Rose Maklès and was also a close friend and colleague of Georges Bataille, to whom Sylvie was briefly married in the 1920s. Lacan moved in Surrealist circles in the 1930s and published some of his earliest research on paranoia in the journal Minotaure, see Alain Grosrichard, "Dr. Lacan, 'Minotaure'; Surrealist Encounters," in Charles Goerg, ed., Focus on Minotaure: The Animal-headed review, exh. cat. (Geneva: Musée d'Art ed d'Histoire, 1987), pp. 159-74. As Derek Sayer has noted, Lacan was also good friends with Masson following his purchase of the artist’s painting Ariadne's Thread in 1939, thus suggesting that the Lacan-Masson-Duchamp connection was "not one of the those uncanny Surrealist coincidences"; Sayer, "Ceci n'est pas un con: Duchamp, Lacan, and L'Origine du monde," in Décimo, ed., Marcel Duchamp and Eroticism, p. 165.

[224] See Elisabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan: Esquisse d’une vie, Historie d’un système de pensée (Paris: Fayars, 1993), p. 249.

[225] See André Masson, "Courbet, Ie Réaliste fabuleux," Critique (Paris), no. 44 (January 1951), pp. 26-29.

[226] Almost two decades after Masson completed his sliding panel for The Origin of the World, Jack Lindsay compared the pictorial structure of Woman with White Stocking to the rocks and tree clumps found in "a typical landscape of the kind that deeply stirred Courbet — the vagina forming the cave-entry, the water-grotto, which recurs in his scenes. The point is worth making because it helps us to see how he created the wonderfully compact pattern of the body here, and how a certain symbolism was present in many of the landscapes."; Lindsay, Gustave Courbet: His Life and Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1973), pp. 217-18. Similarly, Werner Hofmann has associated The Origin of the World with the drawing of a cave entitled the Dame verte from an early Courbet sketchbook in the Musée du Louvre: "What again and again draws Courbet's eye into caves, crevices, and grottoes is the fascination that emanates from the hidden, the impenetrable, but also the longing for security. What is behind this is a pan-erotic mode of experience that perceives in nature a female creature and consequently projects the experience of cave and grotto into the female body"; Hofmann, "Courbets Wirklichkeiten," in Hofmann and Klaus Herding, eds., Courbet und Deutschland, exh. cat., Hamburger Kunsthalle (Cologne: Du Mont, 1978), p. 610; trans. and qupted in Fried, Courbet’s Realism, p. 210.

[227] The fluid, back-anti-forth movement found in Masson's trompe I'oeil panel resonates with the multidirectional flow that Michael Fried has found in Courbet's cave paintings and seascapes, where the foaming water moves both into the painting and outward the painter-beholder; see Fried, Courbet’s Realism, pp. 212-16.

[228] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 2.

[229] Ibid.

[230] Ibid.

[231] Richard Hamilton, quoted in John Russell, "Life in a Peephole," London Sunday Times, October 5, 1969, p. 54.

[232] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," pp. 2, 7.

[233] Duchamp, Manual of Instructions, [p. vii].

[234] Ibid., p. 45.

[235] d'Harnoncourt and Siegl, "Notes on the History of the Tableau," p. 3.

[236] Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, p. 450.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES