Michael R. Taylor

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 1

GENESIS

(Part 1)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 22-26.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

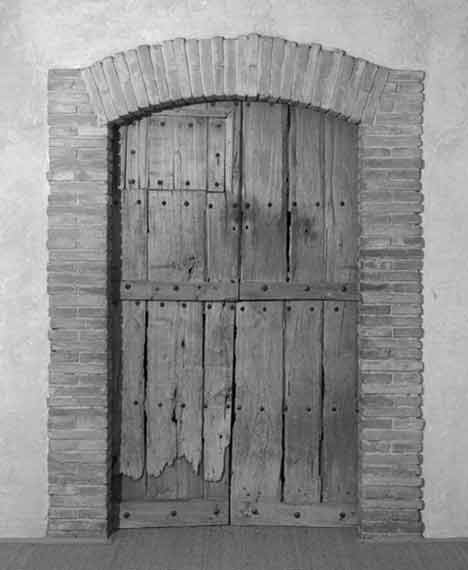

GOING UNDERGROUND

No photograph can ever communicate the unique visual experience of seeing firsthand Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage ... (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas ...), of 1946-66, which has been described by Jasper Johns as "the strangest work of art any museum has ever had in it" (FIG. 1-A1).[1] Permanently installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art since 1969, this elaborate three-dimensional assemblage offers an unforgettable and untranslatable experience to those who peep through the two small holes in the solid wooden door. The unsuspecting viewer encounters a startling sight: a realistically constructed simulacrum of a life-size nude woman lying spread-eagled on a bed of dead twigs and fallen leaves. In her left hand, the mannequin holds aloft an old-fashioned illuminated gas lamp, while behind her, in the far distance, a lush wooded landscape rises toward the horizon. This brightly illuminated backdrop consists of a retouched collotype collage of a hilly landscape with a dense cluster of trees outlined against a hazy turquoise sky, complete with fluffy cotton clouds. The only movement in the otherwise eerily still grotto is a sparkling waterfall (powered by an unseen motor), which pours into a mist-covered lake.

FIG. 1-A1

Marcel Duchamp

Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage ...

(Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas ... ), 1946-66

Exterior of Étant donnés, as installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Mixed-media assemblage.

Exterior: wooden door, iron nails, bricks, and stucco.

Interior: bricks, velvet, wood, parchment over an armature of lead, steel, brass, synthetic putties and adhesives, aluminum sheet, welded steel-wire screen, and Peg-Board, hair, oil paint, plastic, steel binder clips, plastic clothespins, twigs, leaves, glass, plywood, brass piano hinge, nails, screws, cotton, collotype prints, acrylic varnish, chalk, graphite, paper, cardboard, tape, pen ink, electric light fIxtures, gas lamp (Bec Auer type), foam rubber, cork, electric motor, and cookie tin

242.6 × 124.5 × 177.8 cm (951⁄2 × 70 × 49 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of the Cassandra Foundation

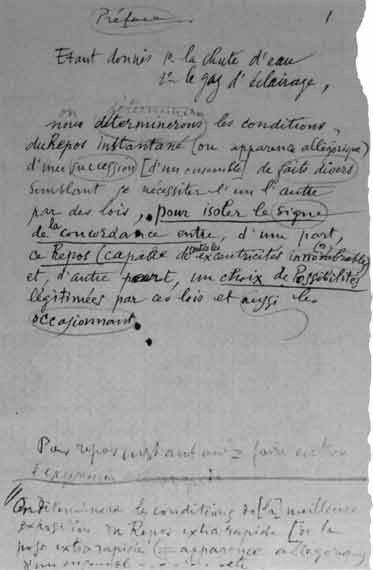

FIG. 1-A2

Marcel Duchamp

"Préface; Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° Ie gaz d'éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas)"

Facsimile (collotype on paper) of manuscript note in

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

(The Green Box), 1934,

21 × 12.7 cm (81⁄4 × 5 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection

---- The pseudoscientific title of Étant donnés has its source in a note by the artist that was first published in 1934 in the collection of note and diagrams known as The Green Box: "Étant donnés 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage ..." (FIG. 1-A2). This note, which Duchamp used as the preface to The Green Box, identifies two of the key elements of Étant donnés, namely, the waterfall and the illuminating gas, both of which were to be included in the artist's great allegory of frustrated desire, La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), also known as The Large Glass, of 1915-23 (see fig. 1.3). Although the waterfall was not executed in the finished work, a note in The Green Box reveals that it was to be a water spout located above the nine Malic Molds in the lower section, or Bachelor domain, of The Large Glass, whose function would be to set the Water Mill in motion. In the end, Duchamp omitted the waterfall from The Large Glass, fearing it would add a conventional landscape feature that would detract from his radical intentions in making a towering painting on two separate planes of glass using nontraditional techniques and materials.[2] Although invisible to the naked eye, the illuminating gas is nonetheless omnipresent in the work as a sexual energy that permeates the Bachelor section. The illuminating gas fills and animates the hollow Malic Molds and escapes through a series of capillary tubes, which act as conduits for circulating the gas throughout the rest of The Large Glass.

---- According to the scenario outlined in The Green Box notes, the nine uniformed Bachelors in the lower panel are perpetually thwarted from copulating with the unattainable biomechanical Bride above. It is thus tempting to imagine that the stripped-bare female in Étant donnés is a three-dimensional embodiment of the elusive, fourth-dimensional figure in the upper section of The Large Glass, who finally has made the transition from Virgin to Bride. This narrative would turn the viewers who peer through the peepholes of Étant donnés into the Témoins oculists (Oculist Witnesses) of the Bride's consummation. The word oculist, which Duchamp borrowed from the French term for the eye chart used by optometrists to test for astigmatism, allows for a risqué pun on au cul to propose that we are all "ass witnesses," or voyeurs who enjoy looking at naked flesh. However, as we shall see, the ease with which one can construct "before and after" connections between The Large Glass and Étant donnés should not blind us to the strong differences between two works that are separated by nearly three decades.

---- Duchamp worked on his climactic tableau-construction in a one-room studio that came rent-free with his tiny, garretlike walk-up apartment on the fifth floor of 210 West Fourteenth Street in New York, halfway between Seventh and Eighth avenues, which he began renting for $35 a month in October 1943.[3] He also used the apartment as a work space, although he eliminated all evidence of art-making in this ostensibly public studio, preferring instead to surround himself with chessboards mounted on the walls or on tabletops, on which he would strategize his moves or practice for upcoming tournaments (see fig. 1.1). A small side door led to a shared bathroom through which one gained access to a locked second room, which Duchamp would use as a studio from 1943 to 1965. It was within the inner sanctuary of this second studio that the artist carried out his final project in complete secrecy, even while entertaining journalists, friends, and other visitors in the next room. As the American Surrealist artist and collector William Nelson Copley observed, if Duchamp "had let it be known he was still working everyone would have been trying to find out what he was up to. But nobody had any interest in what he was doing because nobody, including myself, knew he was doing anything. This gave him all the freedom in the world, for something like twenty years."[4]

Fig. 1.1

Duchamp at a chess board, in his Fourteenth Street studio,

New York, c. 1960

(Sidney J. Waintrob)

Gelatin silver print

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 1.2

Maria Martins, 1941

Unidentified photographer

---- It was probably also in 1943 that the artist met and became infatuated with the Surrealist sculptor Maria Martins (see fig. 1.2), wife of Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, the Brazilian ambassador to the United States. Although the exact circumstances of the first encounter between Duchamp and Martins remain unknown, they probably met in New York through mutual friends in the Surrealist group of artists and writers then in exile from war-torn Europe, or at one of the many exhibition openings they both attended during World War II. It is likely that Duchamp was present at the opening of Martins's exhibition at the Valentine Gallery on March 22, 1943, since this show was combined with an eagerly awaited presentation of recent paintings by Piet Mondrian, making it one of the most significant events of the New York art scene that year.[5] Duchamp's close friend André Breton saw and greatly admired this exhibition of eight recent bronze sculptures by Martins, which she showed under the single name "Maria."[6] It may, therefore, have been the impresario of Surrealism who drew Duchamp's attention to the work of this beautiful and mysterious woman. At that time, Duchamp was still romantically involved with his long-standing companion, the Paris-based American bookbinder Mary Reynolds (fig. 1.4), whom he would continue to see intermittently until her death in 1950, although the artist's famous indifference meant that he remained emotionally unattached and unwilling to commit to a monogamous relationship. Soon after the opening of Martins's 1943 Valentine Gallery exhibition, the two artist began a love affair that lasted until 1950, and inspired Duchamp to use her voluptuous body as the model for the mannequin in Étant donnés, which he began constructing in 1946.[7]

![Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) [La Marée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même], 1915-23. Marcel Duchamp (American, born France, 1887-1968). La Marée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even) (The Large Glass), 1915-23. Oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 277.5x175.9 cm (109¼x69¼ inches). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952-98-1](36/f-3-Duchamp-The-Bride-Stripped-Bare-by-Her-Bachelors-Even.jpg)

Fig. 1.3

Marcel Duchamp

La Marée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même

(The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even)

(The Large Glass), 1915-23.

Oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels

277.5 x 175.9 cm (1091⁄4 x 691⁄4 inches).

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952-98-1

Fig. 1.4

Mary Reynolds and Marcel Duchamp, London, 1937

Costa Achilopulu (?)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- In April 1952, the influential American music critic Winthrop Sargeant visited Duchamp's apartment to conduct an interview for a Life magazine feature profile on the artist entitled "Dada's Daddy." Sargeant was intensely moved by the sixty-four-year-old artist's austere existence in a single room with no kitchen and only a shared bathroom: "It seems a strange place for a high-brow to live," Sargeant wrote, "but that is probably the very reason Duchamp has chosen it—to outwit anyone who might expect him to compromise his individuality by doing the obvious thing .... His rent is $40 a month, fitting into an extremely economical budget by means of which he succeeds in outwitting the whole competitive commercial rat race of New York."[8] William Nelson Copley similarly recalled Duchamp's minimally furnished, dust-filled studio on West Fourteenth Street: "It was a medium-sized room. There was a table with a chess board, one chair, and a packing crate on the other side to sit on, and I guess a bed of some kind in the corner. There was a pile of tobacco ashes on the table, where he used. to clean his pipe. There were two nails in the wall, with a piece of string hanging down from one. And that was all."[9]

---- In the inner sanctum of his humble apartment, without even a telephone to disturb him, Duchamp could work quietly and in complete secrecy on his Étant donnés project. Indeed, he came to view his self-enforced artistic isolation as a powerful alternative to the art market, later famously remarking that "the great artist of tomorrow will go underground."[10] Duchamp uttered this prophecy at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art in 1961, during an artists' panel discussion entitled "Where Do We Go from Here?"[11] He delighted the audience with a verbal assault on the rampant commercialism of the art market, which had turned art into "a commodity like soap or securities." According to Duchamp, "material speculation leads art to a massive dilution, a lowering of taste into the mist of mediocrity," with the only hope being an "ascetic revolution " (a delightful pun on aesthetics and his own spartan lifestyle) that would allow the artist to work outside the gallery system in hermitlike seclusion.

---- This was not the first occasion when Duchamp had connected the precious time he spent alone in his studio with the secluded life of a monk or hermit. As he explained in 1960, "the life of an artist is like the life of a monk," although before his remark could be misconstrued as supporting organized religion, which he detested, Duchamp qualified it with the coda that in his own underground activities he was "a lewd monk ... very Rabelaisian."[12] In a time of political disillusionment and rapacious greed, others also expressed the idea that artists should remove themselves from modern life and go underground. The British art critic Herbert Read, who shared Duchamp's interest in the anarchist writings of the nineteenth-century German thinker Max Stirner and the role of the creative individual in modern society, similarly proposed a return to asceticism in a 1939 essay: "In our decadent society ... art must enter into a monastic phase .... Art must now become individualistic, even hermetic. We must renounce, as the most puerile delusion, the hope that art can ever again perform a social function."[13] Like Duchamp's pronouncements, Read's call for artists to withdraw from social and political engagement must be seen against the background of modern art's failure to oppose fascism. However, Duchamp's interest in hermeticism predated Read's pronouncement and would last for the rest of his lifetime. The Surrealist artist and writer Marcel Jean recalled that in the 1960s Duchamp's response to younger artists who asked if there was any avant-garde activity left open to them was to "go underground, don't let anyone know that you are working."[14]

---- Working "underground," with a minimum of social obligations, gave Duchamp the freedom to focus on Étant donnés in absolute secrecy over a twenty-year period, using drawings and plaster casts of Martins's curvaceous torso as the point of departure for his tableau-construction of a recumbent nude in a bucolic landscape setting. Indeed, he was still finishing the assemblage in late 1965 when his lease expired on the Fourteenth Street studio and he was forced to move to another working space, a small, anonymous room (number 403) on the fourth floor of a commercial building at 80 East Eleventh Street, just a stone's throw from the artist's home at 28 West Tenth Street, where he had lived since November 1, 1959. Duchamp began renting this studio, which had a separate entrance at 799 Broadway, on January I, 1966, and it was there that he would complete his final project two months later.[15]

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 22-26.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[1] Jasper Johns, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the Art World of Our Time (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980), p. 276.

[2] "The wheel [of the Water Mill] which you see inside is supposed to be activated by a waterfall which I did not care to represent to avoid the trap of being a landscape painter again"; Marcel Duchamp, "Apropos of Myself," City Art Museum of St. Louis, MO, November 24,1964, quoted in Anne d'Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art; New York: The Museum of Modern Art; Munich: Prestel, 1973), p. 276.

[3] Anne d'Harnoncourt, interview with the author, Philadelphia, June 28, 2007. According to d'Harnoncourt, Alexina "Teeny" Duchamp, the artist's widow, informed her about this secret, rent-free studio in a telephone conversation on August 10, 1987.

[4] William Nelson Copley, quoted in Alan Jones, "A Conversation with William Copley," in CPLY: William N. Copley, exh. cat. (New York: David Nolan Gallery, 1991), p. 15 (emphasis in the original).

[5] See Maria, New Sculptures, and Mondrian, New Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Valentine Gallery, 1943). This exhibition was on view from March 22 to April 10, 1943.

[6] André Breton later wrote, "Maria's sculpture began to carry a whole legend on its shoulders, a legend that was nothing less than the Amazon itself Sculpture garlanded, like the Amazon's own waters, with tropical creepers. This legend sang in those works of hers which I had the chance to see in New York in 1943 and admired so greatly"; Breton, Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 319-20.

[7] Duchamp's secret love affair with Maria Martins and its implications for his subsequent work were revealed by Francis M. Naumann in a review of the 1993 Duchamp retrospective exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice; see Naumann, "The Bachelor's Quest," Art in America, vol. 81, no. 9 (September 1993), pp. 73-81, 67, 69. In a subsequent article, Naumann supplied further biographical information regarding Duchamp's relationship with Martins, including details of previously unpublished works of art that the artist had given to her, all of which allowed Naumann to elaborate on the theme of sexual frustration that he saw as underpinning the Étant donnés project; see Naumann, "Marcel and Maria," Art in America, vol. 89, no. 4 (April 2001), pp. 99-110, 157.

[8] Winthrop Sargeant, "Dada's Daddy," Life, vol. 32, no. 17 (April 28, 1952), p. 108.

[9] William Nelson Copley, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors: Five Masters of the Avant-Garde; Duchamp, Tinguely, Cage, Rauschenberg, Cunningham (New York: Viking, 1962), p. 61 (emphasis in the original).

[10] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in John Canaday, "Whither Art?" New York Times, March 26, 1961, section 10, p. 15.

[11] Moderated by the art critic Katherine Kuh, this panel was held on March 20, 1961, and also included Louise Nevelson, Larry Day, and Theodoros Stamos.

[12] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Alexander Liberman, The Artist in His Studio (New York: Viking, 1960), p. 57.

[13] Herbert Read, "L'Artiste dans Ie monde moderne" Clé, no. 2 (1939), p. 7, trans. and quoted in Helena Lewis, The Politics of Surrealism (New York: Paragon, 1988), p. 158.

[14] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Marcel Jean, "A Collective Portrait of Marcel Duchamp," in d'Harnoncourt and McShine, Marcel Duchamp, p. 203.

[15] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Barnet Hodes, January 28, 1968, The Art Institute of Chicago, Barnet Hodes Papers.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES