Michael R. Taylor

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 1

GENESIS

(Part 3)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 32-45.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

SURREALISM ON DISPLAY

Although the earliest studies for Étant donnés date to the 1940s, the genesis of the work can be traced back to February 1927, as evidenced by an often overlooked but crucial reference in Julien Levy's autobiography, Memoirs Of an Art Gallery, in which the art dealer recalled a lengthy discussion he had had with Duchamp in the lounge of the transatlantic ocean liner Paris while sailing from New York to Le Havre in February 1927: "Marcel toyed with two flexible pieces of wire, bending and twirling them, occasionally tracing their outline on a piece of paper. He was, he told me, devising a mechanical female apparatus ... a life-size articulated dummy, a mechanical woman whose vagina, contrived of meshed springs and ball bearings, would be contractile, possibly self-lubricating, and activated from a remote control, perhaps located in the head and connected by the leverage of the two wires he was shaping. The apparatus might be used as a sort of 'machineonaniste' without hands."[59]

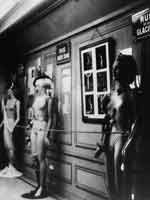

Fig. 1.13

Duchamp's Rrose Sélavy mannequin

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, Galerie Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1938

Raoul Ubac (Belgian, 1910-1985)

Fig. 1.14

Duchamp's Rrose Sélavy mannequin

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, Galerie Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1938

Raoul Ubac (Belgian, 1910-1985)

---- Sadly, the traced drawings to which Levy refers have not survived, but the idea of a life-size, sexually available automaton continued to fascinate Duchamp throughout the interwar period, and no doubt inspired his Rrose Sélavy mannequin (see figs. 1.13 and 1.14) at the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, organized by André Breton and the poet Paul Éluard and held in Paris at Georges Wildenstein's fashionable Galerie Beaux-Arts at 140 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.[60] This androgynous figure took its place in the long corridor of the Rue Surréaliste together with fifteen other half-dressed female mannequins, listed in the exhibition catalogue as having been supplied by "Maison P.L.E.M." and each uniquely outfitted by a different Surrealist artist or writer (see fig. 1.16). The mannequins were evenly spaced about two meters apart in a configuration demarcated by blue enamel street signs on the wall above, some of which used the names of actual streets in Paris, including the Rue Vivienne, where the Surrealist hero and poet Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Ducasse) had lived, and the Passages des Panoramas. The vast majority, however, used made-up names like the Rue de la Transfusion du Sang (Blood Transfusion Street) and the Rue de Tous les Diables (All Devils Street).

Fig. 1.15

André Masson's Mannequin with Birdcage,

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

(Raoul Ubac)

The Getty Research lnstitute, Los Angeles, Research Library, 92.R.76

Fig. 1.16

The Rue Surréaliste

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

with mannequins by unidentified artist (left), Léo Malet (center), and Marcel Jean (right); framed photographs by Hans Bellmer (center)

Josef Breitenbach (German, 1896-1984)

---- Duchamp's Rrose Sélavy mannequin stood under the imaginary Rue aux Lèvres (Street of Lips), as stiff and upright as a sentry but with the come-hither smile of a prostitute. With the economy of means that by this time had become his trademark, Duchamp had dressed the store-bought mannequin in his own tweed jacket, vest, tie, hat, and shoes, adding only a curly blonde wig and an illuminated red lightbulb that bulged out of the breast pocket of the jacket. The seemingly nonchalant and radically simple gesture of placing his own clothes on a female mannequin, whose long eyelashes and manufactured femininity enhanced the effect of transvestitism and imbued the figure with a polymorphous sexual identity, was far removed from the stereotypical male fantasies on display elsewhere, with shop-window dummies shown in various states of undress and fetishistically attired in bizarre accoutrements. These works often presented the mannequin as a victim of sadomasochistic cruelty and sexual violence, seen at its most extreme in Andre Masson's Mannequin with Birdcage—naked except for a plumed cache-sexe (G-string) decorated with eight tigereye gemstones (see fig. 1.15). Her head was encased in an open-door birdcage filled with "swimming" celluloid goldfish and her waist cinched by a red ribbon that gave the impression the body had been sliced in two, while birds nested under her armpits and her mouth was hidden behind a green velvet gag with a purple pansy, rendering her mute and defenseless. Significantly, it was Masson's mannequin, a reflection of patriarchal obsession with woman as an object of desire, that was later singled out for praise by Breton as "Ie premier brillant" (the most brilliant) in the entire display, rather than Duchamp's transgressive, cross-dressing alter ego.[61]

---- The mannequin's lightbulb, which Duchamp powered with an electric cord that can be partially glimpsed in photographs (see fig. 1.13), turned the Rue Surréaliste into a red-light district filled with scantily clad streetwalkers, emphasizing the artist's interest in presenting his scurrilous alter ego as a transgendered prostitute who offered "a complete line of whiskers and kicks."[62] Duchamp signed the work "Rrose Sélavy" on the flattened pubic mound in wispy, dotted handwriting suggestive of pubic hair—a gesture that simultaneously underlined the promise of sexual intercourse and denied it by drawing attention to the artificial nature of her mass-produced body and the complete absence, or lack, of visible genitals and orifices. Over the figure's left shoulder hung two of Duchamp's Rotoreliefs, which when put in motion produced the optical illusion of a rotating wine glass, and over the right a repeating set of bull's horns (see fig. 1.14), the static image of the latter having been used by the artist in 1935 as a cover illustration for the Surrealist magazine Minotaure. When rotated at a certain speed, the Rotoreliefs erotically pulsate in and out in an oscillating movement that simulates anal or vaginal penetration, thus underscoring the gender reversibility and staged artificiality of the Rrose Sélavy mannequin.[63] The use of an electric light source as an erotic "charge" to infuse the work with a frisson of sexual tension also turns this seemingly casual, unimportant work into a powerful precursor of Étant donnés, in which the recumbent, faceless nude holds aloft a lamp emitting the illuminating gas of the work's full title.

---- In the final months of 1937, Breton and Éluard had requested that Duchamp participate in the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme not only through a submission to the exhibition but also as a "générateur-arbitre" (generator-arbitrator) in charge of designing an installation for the work of more than sixty artists from fourteen countries. When the exposition opened, the Rue Surréaliste, leading into the main gallery, or "central grotto," had been transformed by Duchamp into a dark, dank, subterranean space. The walls were painted black and the molded ceiling covered with 1,200 soot-colored coal sacks that where filled with crumpled newspaper and emitted dust and soot on the works and spectators below (fig. 1.17). Under the drooping coal-sack ceiling, visitors encountered an elaborate installation, shrouded in darkness, which featured in each corner a luxuriously appointed double bed made up with silk sheets. In the middle of the room a glowing iron brazier stood on a dais, set on a thickly covered floor of underbrush, moss, clover, and dead leaves surrounding an artificial pond with muddy banks fringed with reeds and ferns.[64]

Fig. 1.17

The central grotto with a view toward the Rue Surréaliste

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

(Josef Breitenbach)

---- The coal-sack ceiling, glistening pool, and thick carpet of dead leaves combined to give the great central hall the appearance of an immense grotto. Duchamp's designs for the 1938 Surrealist exhibition suggest that he was aware of the important place of the grotto in architectural history and the history of ideas. Since Roman times, the grotto has been associated with eroticism, because the creation of secluded architectural spaces that resemble natural caves or springs offer couples the opportunity for hidden lovemaking, to which surviving erotic wall drawings attest. Duchamp's interest in the erotic possibilities of the grotto would continue in the illusionistic landscape environment of Étant donnés, which imbues the work with a sexual charge—suggesting that while the enclosed, artificial space is hidden from the outside world, it is capable of access by voyeurs intent on witnessing the sexual activities within. The grotto also can be connected with his interest in going "underground" and living a secluded life equivalent to that of a cave-dwelling hermit.

---- Architectural historian Naomi Miller has described the concept of the grotto in terms that resonate with Duchamp's construction of grottolike settings in the 1938 Surrealist exhibition and with his subsequent tableau-construction:

The grotto has been the locus of mysterious forces, of unanswered questions, of states of being and becoming. A component in the garden, both earthly and divine, it is the far side of paradise and the paradise within, the beginning and the end. A fancy, a capricious toy, it is born of nature and spun by art for delectation and delight; it is elusive and remote and infinite in its potentials. Perhaps like the proscenium of the theatre, the grotto is above all a metaphorical portal, an entrance, a place of passage. To enter is the significant act; for to enter is to acknowledge the distance between outside and inside, between reality and illusion, between nature and art.[65]

---- The calculatedly disorienting, multisensory atmosphere of this environmental installation was exacerbated by the strong aroma of Brazilian coffee wafting through the room from a coffee-roasting machine installed by the Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret. A hidden soundtrack piped in the competing cacophony of hysterical laughter recorded at an insane asylum, as well as music played by a German marching band. This confusing counterpoint to the visual works of art on display has been interpreted by art historian Elena Filipovic as a reference to the ideological use of museum display exemplified by the Third Reich's simultaneous exhibitions Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exbibition) and Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) in Munich in 1937, the latter of which conflated the art of the European avant-garde with that of the insane and featured Adolf Hitler's voice broadcast over a public-address system.[66] The order, cleanliness, and sobriety of the Great German Art Exhibition installation could not be further removed from the infuriating disorder and chaos of Duchamp's lugubrious, densely hung Surrealist installation, with its dim lighting, blaring acoustics, and unhygienic accumulations of soot, moss, and dirt. His design thus can be seen as a riposte to the idea of stable exhibition display that was central to both modernist and Nazi exhibition practices, which similarly placed special emphasis on spare, linear, antiseptic environments.[67]

---- With sardonic irony, Duchamp later recalled that the ceiling installation was meant to add "a bit of gaiety" to the Surrealist exhibition.[68] In reality, it had the opposite effect, creating a dangerously heavy ceiling and a potential fire hazard, as the artist related in a letter to Julien Levy that amusingly recounted the events surrounding the exhibition. Under the heading "Anecdotes," Duchamp recalled that the "coal sacks on the ceiling (as a ceiling) developed a little panic before opening the show and also on the night of the vernissage [opening]—it was 'scientifically' decided that coal powder produces gas and that the slightest caresse on this gas meant fire (something like coal mine fire, you know) Except for the shivers (human) nothing of the kind happened."[69]

---- The only source of light in this startling mise-en-scène came from the flickering glow of the iron brazier, which was electrically powered but had the appearance of a coal-burning fire. Duchamp originally had intended the works of art on display to be illuminated by electronic "magic eyes" that would be triggered when visitors approached and turned off when they moved on to another work or section of the exhibition.[70] Unfortunately, the motion-sensing technology required to realize this idea was not available in 1938. Although the art historian Sheldon Nodelman has noted that a similar viewer-activated mechanism illuminates the interior of Étant donnés when a visitor steps on a pressure-sensitive sensor hidden under the carpet in the room devoted to the work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art,[71] this hidden electrical device was not part of Duchamp's original plans but rather was installed in 1969 to enhance the life expectancy of the numerous lightbulbs used in the work, thus cutting down on maintenance and costs.

---- In accordance with his long-held principle of not appearing at the openings of exhibitions in which he had been involved, Duchamp refused to attend the vernissage of the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme on January 17, 1938, and took a train to London after completing the installation that afternoon. On opening night, Man Ray, in his role as "maître des lumières" (master of lighting), handed out flashlights to the arriving guests. Visitors also accepted the role of voyeurs as they groped and fumbled through the semidarkness to reach the works of art, which were hung on revolving doors uprooted from a department store and viewed individually by flashlight rather than en masse (fig. 1.18). Before leaving this crowded, claustrophobic space, visitors were confronted by the sight of professional ballet dancer Hélène Vanel, who performed a simulation of hysteria in her improvisational L'Acte manqué (The Unconsummated Act) for the evening opening (fig. 1.19).[72] Dressed in a flesh-revealing white costume, the dancer writhed convulsively, hissing, wailing, and gyrating on the four immense satin-lined brothel beds, splashing in the reed-fringed pond, and at one point even wrestling with a live rooster, compounding the disruptive and disorienting effect of the cavelike central gallery.

Fig. 1.18

Gallery view of the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme,

showing a visitor using a flashlight to view an unidentified painting

(Josef Breitenbach)

Fig. 1.19

Hélène Vanel performing L'Acte manqué (The Unconsummated Act) at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme.

Ubu Gallery, New York, and Galerie Berinson, Berlin

---- Duchamp's subversive, dimly lit installation design thus transformed the elegant eighteenth-century interior of the venerable yet ultrachic Galerie Beaux-Arts into a cross between a coal mine and a deep forest clearing, in which hidden erotic desires were revealed under torchlight. The close proximity of the Rrose Sélavy mannequin to the grottolike environment featuring water, leaves, and other landscape elements, as well as the illuminating gas of the coal-burning metal brazier and coal-sack ceiling, presage the iconography found in the interior of Étant donnés. However, the dioramalike setting of Duchamp's tableau-construction also may owe a debt to another work on display in the exhibition, Salvador Dali's disquieting Rainy Taxi (fig. 1.20a,b), parked outside the entrance of Wildenstein's fashionable gallery and greeted visitors before they reached the lobby and encountered the Rue Surréaliste.

Fig. 1.20a

Salvador Dalí's Rainy Taxi at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme.

Side view of the installation in the courtyard.

André Caillet (dates unknown)

Collection of Timothy Baum.

Fig. 1.20b

Salvador Dalí's Rainy Taxi at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme.

Raoul Ubac. Detail of the driver and passenger.

Collection of Timothy Baum.

---- Inside Dalî's vehicle, which was garlanded with vines, creepers, and flowers, sat two mannequins that were completely drenched by rain falling continuously from the ceiling. In the front seat was a male driver wearing dark goggles and the jawbones of a shark on his head, while in the back seat sat his passenger, a smartly dressed yet disheveled blonde woman covered with some of the two hundred live Burgundy snails that feasted on the lettuce, ivy, and other forms of vegetation that Dalí had scattered throughout the taxi. Beside her on the back seat was a sewing machine, which the Spanish artist no doubt intended as a reference to Lautréamont's famous phrase, "as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissection table,"[73] an image that Breton had referred to as a model of Surrealist dislocation. Duchamp's initial idea to festoon the ceiling of the central grotto with upended umbrellas may have been intended to complement Dalí's sewing machine and complete Lautréamont's poetic juxtaposition. A ceiling filled with umbrellas would have added a humorous, Magritte-like quality that was absent in the conglomeration of black coal sacks that hovered over the visitors like an ominous rain cloud. Unfortunately, Duchamp's idea was abandoned when he was unable to obtain a sufficient quantity of umbrellas in Paris, turning instead to coal sacks, which were freely available and easily stuffed with newspaper. However, Lautréamont's metaphor was completed in the mind of the viewer by the work submitted by the Austrian Surrealist artist Wolfgang Paalen entitled Articulated Cloud, a large mixed-media sculpture of an umbrella that created a dialogue with the sewing machine in Dalí's Rainy Taxi outside.

---- The inclement weather conditions of the interior of Dalí's rented taxicab helped introduce one of the key themes of the exhibition installation, that of the uncanny reversal of indoor and outdoor settings, which was also seen in the fern-fringed pond, dead leaves, and thick moss installed in the grottolike central gallery. This theme persists in the interior scene of Étant donnés, with its mist-laden pond, twinkling waterfall, and bed of twigs, leaves, and branches that Duchamp provided for the mannequin. In the following decade, the voyeuristic aspect of Dalí's Rainy Taxi also may have served as a powerful precursor for Duchamp's elaborate and erotic three-dimensional optical machine, since visitors to the 1938 exhibition were forced to peer through the taxicab's closed windows to view the rain-soaked mannequins and their slimy, snail-infested three-dimensional environment.

---- The tactile, lugubrious, organic, visceral, and highly erotic environment that Duchamp designed established the prototype for all future Surrealist exhibitions, which similarly utilized labyrinthine passageways and controlled lighting and viewing conditions to produce spectacular installations that frequently overwhelmed the, individual works of art on display. By appealing to the senses of touch, smell, and sound, as well as sight, Duchamp's 1938 installation revealed the limitations of painting as a static, two-dimensional medium, and in doing so encouraged increased interaction between the spectator and the work of art that would have important ramifications for Étant donnés.

---- The 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme would be the first of five international Surrealist exhibitions—others were held in 1942, 1947, 1959, and 1960 for which Duchamp would design or generate ideas. Many years later, when the writer Pierre Cabanne asked him about his participation in the 1938 exhibition, Duchamp explained: "I had been borrowed from the ordinary world by the Surrealists. They liked me a lot; Breton liked me a lot; we were very good together. They had a lot of confidence in the ideas I could bring them, ideas which weren't anti-Surrealist, but which weren't always Surrealist, either."[74] The liminal space that Duchamp occupied as an idiosyncratic outsider who was nonetheless sympathetic to the group's aims and ideals, if not its politics, allowed him to subvert the intended meaning and message of the movement for his own ends.[75] As I will argue, the artist used the Surrealist exhibition format as a vehicle for exploring and unloading his ideas, especially those surrounding the Étant donnés project . These disorienting, multisensory environmental displays supplied him with a laboratory-like environment in which he could test his theories, such as the fixed vantage point of the viewer, the eroticization of vision, and the role of the spectator in the creative act.

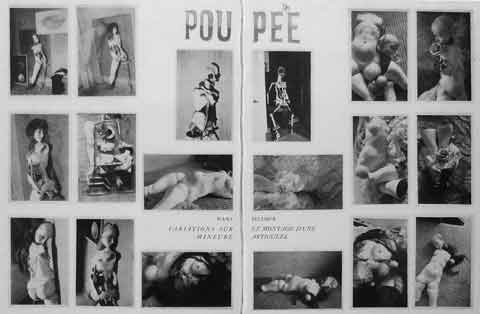

GAMES OF THE DOLL

The Surrealists' long-standing interest in the theme of dolls, mannequins, and automatons began with the mute tailor's dummies of Giorgio de Chirico and was rekindled in the 1930s by the haunting photographs of Hans Bellmer. In 1934 the German artist privately published ten hand-colored photographs of his first doll, made of plaster and papier-mâché over an armature of wood and metal, as Die Puppe (The Doll), which he dedicated to his young cousin Ursula.[76] The images were embraced by Paul Éluard, whose enthusiastic encouragement led the journal Minotaure to reproduce eighteen of Bellmer's pictures as a two-page spread in the Winter 1934-35 issue, under the provocative headline "Poupée: Variations sur Ie montage d'une mineure articulée" (Doll: Variations on the Assemblage of an Articulated Minor; fig. 1.21). The same issue contained Breton's celebrated essay "Lighthouse of the Bride," which Duchamp admired as one of the best critical interpretations of his Large Glass, suggesting that he was indeed aware of Bellmer's photographs by the mid-1930s.[77] Although Bellmer did not submit a mannequin to the 1938 Surrealist exhibition, two sets of his extraordinary photographs of the voluptuous second doll, La Poupée, which he constructed in 1935-36, were interspersed among the pairs of mannequins that stood at the beginning and end of the corridor installation, thus adding a sinister atmosphere of danger, dismemberment, and defilement to the Rue Surréaliste (fig. 1.22).

Fig. 1.21

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

Poupée (Doll), 1935,

published in Minotaure, Winter 1934-35

Fig. 1.22

Hans Bellmer

La Poupée (The Doll), 1935

Gelatin silver print on stretcher, 66×66 cm (26×26 inches)

Ubu Gallery, New York, and Galerie Berinson, Berlin

---- Duchamp's prominent role as generator-arbitrator in the visual design of the 1938 Surrealist exhibition confirms that he was alert to the transgressive nature of Bellmer's disquieting doll photographs, especially at a time when he was exploring his own mannequin project. In 1935, Bellmer prepared a second publication, for which Paul Éluard wrote fourteen prose poems. Although this portfolio did not appear until 1949, when it was published under the title Les Jeux de fa poupée (Games of the Doll),[78] the German artist's photographs were circulated widely among the Surrealists. These images were hand-colored with aniline paint to heighten the sense of artificiality and strangeness of the doll in her various configurations. Bellmer's photographs of his second doll, a fragmented, frequently armless, and sometimes headless female with multiple limbs and orifices, would in my opinion have a profound impact on Duchamp's Étant donnés as it developed in the 1940s.

---- Whereas Bellmer's rudimentary first doll, which caused a sensation when it was featured in Minotaure, had a rough plaster-of-paris surface, the second doll had smoother skin made out of strong glue and tissue paper and painted to resemble human flesh. The limbs of this second figure pivoted around a central ball-and-socket system of articulation, and could be detached and rearranged in a variety of anatomical formations that the artist described as "anagrams" of the body.[79] Bellmer made more than one hundred photographs of his articulated doll and its various appendages, which he compulsively reconstructed in an astonishing variety of sadomasochistic scenarios, including exterior shots of the disembodied figure standing in a wooded landscape and reclining spread-eagled in a hayloft (fig. 1.23). This image may have inspired Duchamp's later installation of a splayed and truncated body reclining on a bed of twigs in a rustic, outdoor setting. Similarly, Bellmer's 1934 drawings of the doll's curvaceous, disassembled forms seen through a splintered aperture in a wooden door (fig. 1.24) might have supplied Duchamp with a model for the peephole viewing apparatus of his own work, which he began in the following decade.

Fig. 1.23

Hans Bellmer

La Poupée (Doll Abandoned in Hayloft), 1938

Vintage gelatin silver print, 14.2 × 14.5 cm (59⁄16 × 511⁄16 inches)

Ubu Gallery, New York, and Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Fig. 1.24

Hans Bellmer

Untitled, 1934

Pencil and white gouache on colored paper

16.5 × 26.7 cm (61⁄2 × 101⁄2 inches)

Isidore Ducasse Fine Arts, New York

---- Despite their shared interest in eroticism and the liberation of sexual desire, Duchamp's work and ideas are far removed from the deep alienation of Bellmer's tortured imagination. The mature and voluptuous nude body of Duchamp's splayed mannequin contrasts starkly with Bellmer's perverse fantasies of nimble and coy yet all - too-knowing young girls in a state of arrested adolescence, whose "pink realm" he feared would forever elude him.[80] As art historian Therese Lichtenstein has shown, Bellmer's prodigious agglomerations of fragmented body parts offer striking meditations on the psychodynamics of fascism and the cult of health, Aryan physical perfection, and sexual "normality" in Nazi ideology.[81] Although Duchamp's clandestine construction of the figure and landscape in Étant donnés took place after the defeat of fascism and the conclusion of World War II, his attempt to radically redefine the erotic domain through the subversive sexuality of a hyperrealistic work of art shares many similarities with Bellmer's fetishistic manipulations of his meticulously constructed doll sculptures. Working in virtual seclusion, both artists reconstructed the anatomy of the female body as a means to test the limits of representation, perhaps explaining why their works not only invoke in the spectator the seemingly contradictory reactions of attraction and repulsion, but also elicit frequent charges of irredeemable misogyny and sexual violence, despite the fact that neither artist ever resorted to such shock tactics as blood or open wounds in their anatomical realignments.

Fig. 1.25

Alma Mahler doll made by Hermine Moos for Oscar Kokoschka, c. 1919-22

---- A less direct but equally fascinating predecessor of the Étant donnés mannequin is the doll that the Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka commissioned while living and teaching in Dresden in 1918, following the breakup of his tense and often tumultuous three-year relationship with Alma Mahler, the widow of the composer Gustav Mahler, better known during his lifetime as the conductor of the Vienna Opera. The life-size fetish (fig. 1.25) was constructed in wood and fabric by Hermine Moos, a Stuttgart-based seamstress and dollmaker who worked from Kokoschka's detailed and elaborate drawings and written instructions. The artist's specifications reveal a Faustian drive to transcend natural limitations and create a living, breathing automaton. The doll was designed as a replica of his former love, down to her hand-painted features and wig of chestnut hair, and functioned as a passive and obliging substitute for the woman with whom he constantly quarreled and who ultimately rejected him. In anticipation of the arrival of this lovingly planned "woman of my dreams,"[82] Kokoschka hired a horse and carriage so that he could take her out on sunny days, and reserved a box at the opera to show her off to the crowded house.[83] Unfortunately, when the package arrived the newly constructed "goddess" did not match his exalted expectations. The artist was repelled by the fur-covered body, which he had hoped would be smooth and fleshlike: "The outer shell is a polar-bear pelt," Kokoschka complained to Moos, "suitable for a shaggy imitation bedside rug rather than the soft and pliable skin of a woman."[84]

---- Photographs of the limp and lifeless doll make plain the reasons for the artist's disappointment in his artificial "princess," since the masklike face and the stuffed body's bulging protuberances prevented Kokoschka from carrying out his plan of dressing her in "delicate and precious robes"[85] and failed to capture the uncanny verisimilitude he was seeking. The reclining automaton appears in several paintings and drawings that emphasize her transgressive status as an inanimate object of repressed desire (fig. 1.26).[86] Eventually, however, Kokoschka grew tired of the charade, and in the summer of 1920 he threw a large farewell party in his Dresden studio for the "Silent Woman," as he had christened this monstrous surrogate for Alma. The motionless dummy was paraded in front of his friends as though she were a model in a fashion show, accompanied by music supplied by the Dresden Opera Chamber Orchestra. Toward the end of the evening, as the incubus was passed from guest to guest, the party quickly turned into a wild orgy of drunken violence, and the effigy of Alma seems to have been attacked, beheaded, and doused in red wine, a metaphor for the blood that her body lacked.[87]

Fig. 1.26

Oscar Kokoschka

Self-Portrait with Doll, 1922

Oil on canvas, 80 × 120 cm (311⁄2 × 471⁄4 inches)

Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

---- Kokoschka's account of this disturbing event, in which the wine/blood and the loss of the head neatly function as classic Freudian castration images, suggested the artist's fear of the phallic doll he had made and must destroy. The artist ended his story by concluding that "the doll was an image of spent love that no Pygmalion could bring to life."[88] Like Bellmer and Duchamp, Kokoschka undoubtedly was aware of E.T.A. Hoffmann's widely published and translated story The Sandman (1817), whose protagonist Nathaniel, a psychologically distraught student, falls in love with a beautiful wooden clockwork automaton named Olympia, with tragic results. Hoffmann's story became a key example of Sigmund Freud's notions of the uncanny and the castration complex. His analysis of the confusion over "whether an apparently animate being is really alive, or conversely whether a lifeless object might not be in fact inanimate"[89] can be applied to the work of all three artists, whose manipulable humanoid dummies function, to varying degrees, as surrogates for unrequited love and forbidden desire.

---- Only Kokoschka, it seems, would exorcise the memory of the lover who spurned him by destroying the fantasy that had dominated his imagination. The dolls Bellmer constructed and recorded in his subsequent photographs were initially inspired by his young cousin Ursula, who would remain an important touchstone for the corporeal metamorphoses he produced over the next four decades, even after she had been replaced in his personal life by other companions, such as Nora Mitrani and Unica Zürn.[90] In the fall of 1932, Bellmer attended a performance of Jacques Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann with Ursula, and his fertile imagination may have connected the lifelike mechanical doll of Hoffmann's novella, which forms the first act of Offenbach's opera, to his sublimated desire for his coquettish adolescent cousin, with whom he was infatuated to the point of tormented agony. As Duchamp's letters from the early 1950s attest, he was similarly unable to expunge the memory of Maria Martins, whose body casts provided the raw materials to construct the Étant donnés mannequin, and the finished work retained the erotic frisson of their love affair, which had ended nearly two decades earlier.

SURREALISM IN EXILE

The transition from a naked mannequin, possibly self-lubricating and operated by remote control, to a peephole installation featuring a Bellmer-like tableau of a recumbent nude in a secluded wooded setting appears to have taken place in the early 1940s, at a time when Duchamp once again was actively involved in Surrealist exhibition design. Indeed, a close examination of the history of Étant donnés and its covert construction reveals that Duchamp was responding to the changing conditions of Surrealism both during and after the war, when the core members of Breton's exiled group in New York embraced not only tarot cards, black magic, pagan rituals, hermetic philosophy, alchemical, cabalistic, and other forms of arcane imagery, and modern physics, but above all a new conception of Eros, as art historian Alyce Mahon has persuasively argued.[91] In an interview with the American writer and editor Charles Henri Ford that appeared in View magazine in August 1941, shortly after Breton arrived in New York, the Surrealist poet declared that the appropriate response to the human suffering caused by World War II was to "learn to read with and look, in time to come, through the eyes of Eros—Eros who will have the task of reestablishing that equilibrium briefly broken for the benefit of death."[92]

---- After escaping Nazi-occupied France, Duchamp arrived in New York on a Portuguese refugee ship, the SS Serpa Pinto, which docked at Staten Island on June 25, 1942. Five days later, at a party Breton threw for Duchamp in the writer's fifth-floor apartment at 265 West Eleventh Street in Greenwich Village, it became clear that the Surrealist leader was looking for guidance and support in this strange country, whose language he pointedly refused to learn, believing that it would diminish the cadence of his poetry and dilute his perfect mastery of French. Duchamp's calm demeanor and humorous disposition were diametrically opposed to Breton's ferocious temper and uncompromising approach to those who strayed from the official party line. The lion-maned poet was now head of a fractious, geopolitically displaced group that had grown increasingly weary of his intolerance and overbearing countenance, and that had used the freedom of a new country and an influx of fresh members to challenge his rigid control of the movement. Duchamp thus arrived at a time when the formerly charismatic leader was at his most vulnerable, besieged by a series of crises, defections, insults, and disappointments. In a letter to the British Surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford, penned shortly after the party at Breton's apartment, the writer expressed elation at his friend's arrival: "Duchamp is in New York. That is the most beautiful acquisition we have had."[93]

---- Breton had admired Duchamp's "marvelous intelligence" since their first meeting in Paris in 1921,[94] although he had been aware of the artist's work and ideas as early as 1917 through their mutual friend, the avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire.[95] Nine years older than Breton, Duchamp at first intrigued the young poet and future leader of the Surrealist group, who appreciated the artist's aloof detachment at a time when Breton was surrounded by sycophantic acolytes who hung on his every word; but the writer later grew exasperated by Duchamp's lack of political engagement and denounced him in 1929 as a failure for his artistic inactivity.[96] Eventually setting aside the artist's famous indifference to art and politics, Breton came to recognize Duchamp as "the great hidden inspirer"[97] of Surrealism, especially in the 1940s, when his absolute integrity and openness to new forms of creative expression helped to revive the movement's fortunes in its darkest hour.

---- Breton regarded the artist as "indispensable to the cause of Surrealism,"[98] and the American Surrealist painter Enrico Donati remembered the writer's sense of relief at Duchamp's arrival from France, as well as his adulation of Duchamp's intellectual and artistic ideas:

Breton needed Duchamp's help in New York, which was a city that he just couldn't fathom .... I remember the first time I met Duchamp, which was at a famous restaurant called Larré on West 56th Street. We had a huge table in front of the window and there was Jacqueline Breton, [Nicolas] Calas, [Frederick] Kiesler, [Roberto] Matta, [Kurt] Seligmann, Isabelle Waldberg, you name it, everybody was there. Breton had a seat facing the outside window, so he could see the people coming in and wave to them so they would come to the table. Anyway, in comes a man that Breton clearly admired tremendously. He jumped up like he had a spring under his seat when he saw this guy through the window and began waving frantically to get his attention. When the man came over, Breton started to bow in front of him, Japanese style. Several times he bowed in front of this guy, like it was God appearing. He looked very distinguished, dressed up in navy blue, with a pure white shirt, and smoking a pipe. He didn't look like a painter at all, so I was amazed when Breton introduced him to me as Marcel Duchamp.[99]

---- Breton had hoped to replicate in New York the stimulating intellectual atmosphere of Paris between the wars, when the Surrealists met regularly at their favorite cafes and restaurants. However, it soon became apparent that restaurants like Larré could not take the place of Deux Magots in Paris, and without effective leadership exiled Surrealist artists such as Max Ernst, Andre Masson, Kurt Seligmann, and Yves Tanguy initially maintained a solitary existence, keeping to themselves, speaking French, and making little or no contact with the fledgling American avant-garde. Ernst later recalled the negative effect that New York's lack of a cafe culture had on the possibilities of Surrealist meetings: "It was hard to see one another in New York. ... In Paris at 6 o'clock on any evening you knew on what café terraces you could find Giacometti or Éluard. Here you would have to 'phone and make an appointment in advance .... Such a communal life as that of the Paris café is difficult—if not impossible here."[100]

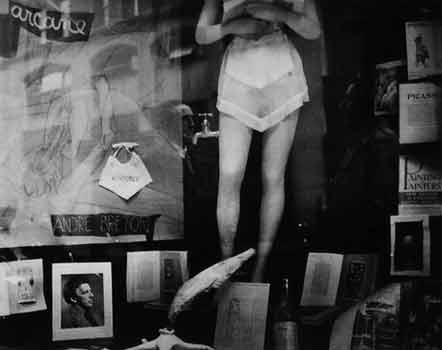

---- Breton's stubborn refusal to assimilate to his new life in the United States meant that he was unable to attract large numbers of new adherents to the Surrealist movement, nor could he maintain control of the group without further damaging its reputation and alienating its existing members. In a move that was to have important ramifications for both men as well as for the future of the international movement, Breton decided to temporarily cede leadership of the still powerful yet flailing Surrealist group to Duchamp afor the duration of the war, while he worked as a radio announcer on La Voix de l'Amérique en guerre (The Voice of America at War), an occupation he intensely disliked but believed was important to the worldwide fight against fascism. Duchamp's fluent English, his nonconformist attitude toward life and art, and his exceptional contacts in the New York art world made him far and away the best-qualified person to steer the group during this time of exile and crisis. Under his de facto direction, Surrealism was suddenly transformed into an inclusive, interdisciplinary, and less authoritarian and hierarchical movement one—that was "for each person and open for everybody," to quote Willem de Kooning's famous description of the artist himself.[101] This transfer of power was symbolically represented in an April 1945 photograph by Maya Deren in which the facing profiles of Duchamp and Breton are reflected in a window display at the Gotham Book Mart, located at 51 West Forty-seventh Street in New York, that was designed to promote the Surrealist writer's new book, Arcanum 17 (fig. 1.27). The photograph no doubt was intended to record Duchamp's Lazy Hardware installation, in which a headless, nearly nude female mannequin with a faucet attached to her right thigh was shown alongside Surrealist works of art, books, and magazines, as well as photographs of Duchamp and Breton. In Deren's photograph, the artist's reflection appears above an image of a youthful Breton, while the reflection of the Surrealist writer is shown above Duchamp's Self–Portrait at the Age of 85, suggesting an unwritten yet mutually agreed on exchange of roles, whereby the older artist temporarily displaced his young friend as the leader of the exiled Surrealist group for the duration of the war. Between his arrival in New York in June 1942 and his departure in May 1946 for an extended stay in Paris, Duchamp found himself at the epicenter of an exciting cultural milieu in which emigré Surrealists like Nicolas Calas, Max Ernst, André Masson, and Roberto Matta interacted with younger American writers and artists, including Enrico Donati, Arshile Gorky, David Hare, and Leon Kelly.[102] In contrast to Breton's combative personality and notorious homophobia, Duchamp's non-confrontational attitude and open-minded tolerance of same-sex relationships allowed a new generation of gay artists and writers to associate with the Surrealist movement without fear of censorship or excommunication. As art historian Robert Harvey has noted, Duchamp's "otherness," combined with the sheer endearing qualities of the man—including his innate lovability—resolutely "queered the field" and shaped Surrealism during World War II.[103]

Fig. 1.27

Maya Deren. Marcel Duchamp's installation Lazy Hardware, Gotham Book Mart, New York, 1945

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- Much to Breton's consternation, the magazine View, which was sympathetic to Surrealism, was edited by Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, both of whom were openly homosexual and therefore would have been excluded from the movement in Paris. Thanks to Duchamp's preeminent position as the effective leader of Surrealism during its period of exile in New York, Ford and Tyler were allowed to publish their magazine without fear of suppression or rebuke. Indeed, it is a tribute to the respect and high esteem in which the other artists and writers held Duchamp, as well as his consummate ability as a peacemaker to resolve disputes to everyone's satisfaction, that he was able to unify what had been a divisive and fractious movement, especially in the years leading up to the outbreak of World War II, "when Surrealism could have been fitted with a turnstile," to borrow art historian Gavin Parkinson's memorable phrase.[104]

---- After failing to adequately oppose and defeat fascism in Europe, the Surrealists hoped to reinvent themselves in the new world. One of their strategies to achieve this goal was to create new myths on which a future society could be based, displacing the outmoded economic model of capitalism and the failed utopia of communism. In the "Prologemena to a Third Manifesto or Not," Breton proposed the new myth of "Les Grands Transparents" (The Great Transparents, or The Great Invisibles), which he derived from the writings of William James and the German Romantic poet Novalis. The Great Transparents were invisible entities that surrounded human beings but remained undetected by the five senses. "Man is perhaps not the center, the cynosure of the universe," wrote Breton in 1942. "One can go so far as to believe that there exists above him, on the animal scale, beings whose behavior is as strange to him as his may be to the mayfly or the whale. Nothing necessarily stands in the way of these creatures' being able to completely escape man's sensory system of references through a camouflage of whatever sort one cares to imagine, though the possibility of such a camouflage is posited only by the theory of forms and the study of mimetic animals."[105] The transcendental escapism of this collective social myth appealed to younger artists like Gorky, Hare, Jacques Hérold, Gerome Kamrowski, Matta, and Lee Mullican, who used it as the basis for their biomorphic imagery, in which the mysterious, imperceptible creatures often can be discerned in compositions that otherwise would hover on the brink of total abstraction.

---- As Surrealism recast itself in the 1940s under the aegis of the apolitical Duchamp, its earlier faith in Marxist revolution was replaced with utopian humanist ideals inspired by Breton's rediscovery of the nineteenth-century French social theorist Charles Fourier, whose advocacy of free love encouraged the Surrealists to redefine their notions of eroticism and the sexual act.[106] In opposition to the war-ravaged world around them, Surrealism's protagonists increasingly turned to an interior world, such as the one seen behind the massive Spanish wooden door in Étant donnés, which separates the viewer from an unexpected and unimaginable landscape, an embodied mystery visible only to those who look through the peepholes, as into a dream.

GENESIS (Part 1) - GENESIS (Part 2) - GENESIS (Part 3) - GENESIS (Part 4)

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,

Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press,

2009, pp. 45-54.

(Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15, 2009-Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[59] Julien Levy, Memoirs of an Art Gallery (New York: Putnam's, 1977), p. 20.

[60] The details of this exhibition have been documented by several of the participants, whose accounts, while often lively and filled with colorful detail, also are largely reliable; see, for example, Georges Hugnet, "L'Exposition international du surréalisme en 1938," Preuves, no. 91 (September 1958), pp. 39 47; Marcel Jean, The History of Surrealist Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Grove, 1960); Man Ray, Self Portrait (Boston: Little, Brown, 1963); and Léo Malet, Le Vache enragée (Paris: Hoëbeke, 1988). The exhibition also has been disscussed at length in Daniel Abadie, "L'Exposition international du surréalisme, Paris 1938," in Paris/Paris, 1937-1957:Creations en France, pp. 72-74, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1981); and Germano Celant, "A Visual Machine: Art Installation and Its Modern Archetypes," in Reesa Goldberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, and Sandy Nairne, eds., Thinking About Exhibitions (London: Routledge, 1996), pp. 371-86.

[61] Andre Breton, "Prestige d'André Masson," Minotaure (Paris), nos. 11-12 (May 1939), p. 13.

[62] See Michael R. Taylor, "Rrose Sélavy, prostituée de la Rue aux Lèvres: Levant Ie voile sur l'alter ego érotique de Marcel Duchamp," in Marie-Lauré Bernadac and Bernard Marcadé, eds., Fémininmasculin: Le Sexe de l'art, exh. cat. (Paris: GaIIimard/Electa: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1995), pp. 284-90.

[63] Rosalind E. Krauss has convincingly connected the Rotoreliefs with images of modern industry such as flywheels, turnscrews, and propellers. Duchamp's brightly colored spheres and helixes, which at certain moments appear to recede and at others to thrust forward in a movement suggestive of sexual penetration, thus offer a fleeting, temporal, carnal space of resistance to rationalization; see Krauss, The Optical Unconscious (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), p. 142. This interpretation would also explain their presence in the Rue Surréaliste, where the mannequins lining the corridor restaged the commodity fetishism of the commercial shop-window display.

[64] See Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking, 1971), p. 81. Duchamp told Cabanne that it was his idea to create a central grotto with twelve hundred coal sacks filled with newspaper and suspended from the ceiling, but that the pond was Dali's idea; ibid.

[65] Naomi Miller, Heavenly Caves: Reflections on the Garden Grotto (New York: Braziller, 1982), p. 123.

[66] See Elena Filipovic, "Surrealism in 1938: The Exhibition at War," in Raymond Spiteri and Donald LaCoss, eds., Surrealism, Politics and Culture (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003). pp. 179-203.

[67] Ibid., p. 183.

[68] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Otto Hahn, "G2553000" (interview with Marcel Duchamp), traIlS. Andrew Rabeneck, Art and Artists (London), vol. 1, no. 4 (July 1966), p. 9. "G2553000" was the number of Duchamp's U.S. passport.

[69] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Julien Levy, March 17, 1938, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Julien Levy Papers.

[70] See Jean, History of Surrealist Painting, pp. 281-82.

[71] See Sheldon Nodelman, "Duchampiana I: Disguise and Display," Art in America, vol. 91 , no. 3 (March 2003), p. 59.

[72] See Hugnet, "L'Exposition international du surréalisme en 1938," pp. 45-46.

[73] Comte de Lautréamont, Les Chants de Maldoror, Chant IV.1 (1869).

[74] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 81.

[75] In recent years, there has been a surge of academic interest in the history and reception of Surrealist exhibitions. My own thinking on the subject has benefited greatly from several previous studies, including Bruce Altshuler, The Avant-Garde in Exhibition: New Art in the Twentieth Century (New York: Abrams, 1994); Lewis Kachur, Displaying the Marvelous: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Surrealist Exhibition Installations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001); Elena Filipovic, Marcel Duchamp on Display: Optics, Exhibition Installations, Portable Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Zabriskie Gallery, 2001); and Alyce Mahon, Surrealism and the Politics of Eros, 1938-1968 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005).

[76] Die Puppe was printed privately in 1934 in a deluxe edition by Thomas Eckstein in Karlsruhe, Germany.

[77] See André Breton, "Lighthouse of the Bride," View, ser. 5, no. 1 (March 1945), pp. 6-9, 13.

[78] See Hans Bellmer, Les feux de la poupée (Paris: Éditions Premières, 1949).

[79] See Peter Webb, Hans Bellmer (London: Quartet, 1985), p. 172. As Alyce Mahon has argued, Bellmer used his anagrammatic art and writing "as a tool of provocation to demand an active, self-conscious role for the reader/viewer and, by extension, to deconstruct the totalitarian body politic of Nazi Germany in which anyone that did not conform to or fit into a fascist Aryan ideal was made Other, objectified, repressed and ultimately destroyed"; Mahon, "Hans Bellmer's Libidinal Politics," in Spiteri and LaCoss, Surrealism, Politics and Culture, p. 249.

[80] Hans Bellmer, "The Doll," in Michael Semff and Anthony Spira, eds., Hans Bellmer, exh. cat., Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, Pinakothek der Moderne (Ostfildern, Gemany: Hatje Cantz, 2006), p. 52.

[81] See Therese Lichtenstein, Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer (Berkeley: University of California Press; New York: International Center of Photography, 2001).

[82] Oskar Kokoschka, quoted in Susanne Keegan, The Eye of God: A Life of Oskar Kokoschka (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), p. 106.

[83] See Edith Hoffmann, Kokoschka: Life and Work (London: Faber and Faber, 1947), p. 148.

[84] Oskar Kokoschka, quoted in Keegan, Eye if God, pp. 115-16.

[85] Oskar Kokoschka, quoted in ibid., pp. 107, 115.

[86] Kokoschka's paintings and drawings of the doll, as well as photographs of Moos's construction, are reproduced in Klaus Gallwitz and Stephan Mann, eds., Oskar Kokoschka und Alma Mahler: Die Puppe; Epilog einer Passion, exh. cat. (Frankfurt am Main: Städtische Galerie im Städel, 1992).

[87] See Frank Whitford, Oskar Kokoschka: A Life (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986), p. 125.

[88] Oskar Kokoschka, My Life, trans. David Britt (New York: Macmillan, 1974), p. 118.

[89] Ernst Jentsch, quoted by Sigmund Freud, "The 'Uncanny,'" in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17, trans. and ed. James Srrachey (London: Hogarth, 1953-74), p. 226.

[90] Rosalind E. Krauss approaches Bellmer's work through Freud's notion of the uncanny, and suggests that the poupées convey the "Medusa effect"—that is, a multiplication of castration symbols represented by the doll's decomposition from multiple, pneumatic limbs; see Krauss, "Corpus Delicti," in Krauss and Jane Livingston, eds., L'Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: The Corcoran Gallery of Art; New York: Abbeville, 1985), p. 86.

[91] See Mahon, Surrealism and the Politics of Eros.

[92] André Breton, quoted in Charles Henri Ford, "Interview with André Breton," View, vol. I, nos. 7-8 (October-November 1941), p. 1.

[93] André Breton, letter to Gordon Onslow Ford, summer 1942, quoted in Martica Sawin, Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning if the New York School (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), p. 225.

[94] André Breton published an enthusiastic report of their first encounter in the following year; see Breton, "Marcel Duchamp," Littérature (Paris), n.s., no. 5 (October 1922), pp. 7-10, repro in Breton, The Lost Steps, trans. Mark Polizzotti (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), pp. 85-88.

[95] See Robert Lebel, "Marcel Duchamp and André Breton," in d'Harnoncourt and McShine, Marcel Duchamp, p. 137.

[96] Sec André Breton, "Second Manifesto of Surrealism," in Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), p. 170. As Gavin Parkinson has noted, Breton's subtle denunciation of Duchamp's decision to abandon art for an "interminable game of chess" involved a tripartite pun on the French word échecs, which can be read as "chess," "check," and "failure." Within the context of the Second Manifesto, in which Breton similarly condemned Arthur Rimbaud's earlier decision to abandon poetry, the word clearly is used to denounce the artist's inactivity as a failure; see Parkinson, The Duchamp Book (London: Tate, 2008), p. 37.

[97] Andre Breton, Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism, trans. Mark Polizzotti (New York: Marlowe, 1993), p. 201.

[98] Lebel, "Marcel Duchamp and André Breton," p. 135.

[99] Enrico Donati, interview with the author, New York, December 14, 2006.

[100] Max Ernst, quoted in George Melly, Paris and the Surrealists (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991), p. 70.

[101] Willem de Kooning, "What Abstract Art Means to Me," Bulletin if the Museum of Modern Art, vol. 18, no. 3 (June 1951), p. 7.

[102] On May 1, 1946, Duchamp boarded the SS Brasil of the Cunard Line to sail for France, where he would spend the next eight months visiting family members and working on ideas for the 1947 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, before returning to New York in January 1947. Prior to this trip, the artist informed Tristan Tzara, his friend and former colleague in Paris Dada, that he was not looking forward to seeing the French capital again: "The way they're all at each other's throats doesn't do anything for me. Here, on the other hand, the ordinariness of life provides a kind of tranquillity"; Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk, eds., Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, trans. Jill Taylor (Ghent, Belgium: Ludion, 2000), pp. 253-54.

[103] See Robert Harvey, "Where's Duchamp?—Out Queering the Field," in Katherine Conley and Pierre Taminiaux, eds., Surrealism and Its Others, Yale French Studies, no. 109 (2006), pp. 82-97.

[104] Gavin Parkinson, Surrealism, Art and Model n Science: Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Epistemology (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 99.

[105] André Breton, "Prologemena to a Third Manifesto or Not" (1942), in Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, p. 293 (emphasis in the original).

[106] Breton later celebrated Fourier's conception of an amorous utopia, in which the law of passionate attraction would inaugurate universal happiness, in his poem Ode à Charles Fourier (Paris: Revue Fontaine, 1947), repro in Andre Breton, Ode to Charles Fourier, trans. Kenneth White (London: Cape Goliard, 1969).

BIBLIOGRAPHIES