Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Michael R. Taylor

The Genesis, Construction, Installation, and Legacy of a Secret Masterwork

Chapter 2

CONSTRUCTION (Part 1)*

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 61-75, pp. 120-121. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

---- Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

H(IERONYMOUS) DUCHAMP

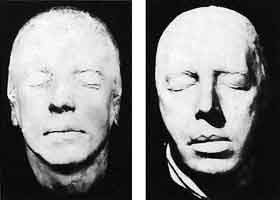

Although there are no written accounts of the making of Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage ..., it is possible to propose a general timeline of its construction by referring to the various materials Duchamp used to assemble the work, his letters to Maria Martins, the memories of Alexina "Teeny" Duchamp, who was the artist's second wife,[1] and technical research conducted at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This research is described in essays by Andrew Lins, Melissa S. Meighan, and Beth A. Price, Ken Sutherland, Scott Homolka, and Elena Torok (see Technical essays in Michael R. Taylor; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009.), and provides new information on Duchamp's materials and methods. The artist's correspondence confirms Teeny's recollection that the nude was the first part of the fullscale assemblage to be constructed, for which Duchamp and Martins took private lessons in body casting in the 1940s from Ettore Salvatore, an Italian-born sculptor who was an instructor in sculpture and casting techniques at Columbia University between 1937 and 1968.[2] Salvatore specialized in life and death masks and even made a rather morbid portrait of Duchamp that was cast from life yet contains the deathly stillness of a funerary effigy (fig. 2.1). Duchamp was no doubt familiar at that time with the life masks of André Breton and Paul Éluard (fig. 2.2), which the French sculptor René Iché made about 1930,[3] since he would have seen this haunting pair of ghostlike visages hanging face-to-face in Breton's studio on the rue Fontaine in Paris. However, these monuments to the Surrealists' belief in the omnipotence of dreams, and seeing the world through closed eyes, are far removed from Duchamp's life mask, which relates instead to his interest in molds and body casts as he prepared to create the Étant donnés mannequin based on Martins's torso.

Fig. 2.1

Ettore Salvatore (American, born Italy, 1902-1990)

Life mask of Marcel Duchamp, c. 1945

Plaster

Collection of Dr. Arthur Brandt

Fig. 2.2

Réne Iché (French, 1897-1954)

Life masks of Paul Éluard (left) and André Breton (right), c. 1930

Plaster

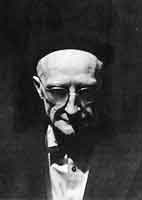

---- The life mask is undated but almost certainly was made about 1945, since the grueling casting session that the artist underwent to make the portrait was vividly captured in a remarkable photograph published in a special Duchamp issue of View magazine later that year, under the mordant title Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85 (see fig. 2.3).[4] Salvatore followed standard casting techniques that must have been close to those described in The Craftsman's Handbook (c. 1400) by Cennino Cennini,[5] a book that he owned and made frequent use of in his artistic practice. The sculptor inserted breathing rubes into Duchamp's nostrils and asked him to wear a rubber bathing cap to protect his hair during the casting process; as a result, he has the appearance of a much older man who has lost his hair. Another photograph, taken at the same time but showing Duchamp without his glasses (see fig. 2.4), makes it clear that the artist replaced the bathing cap with a beret for the View photograph. These images, which were taken by the photographer Percy Rainford on January 13, 1945,[6] must have been made shortly after the session with Salvatore, since Duchamp's face, stubble, and hairline reveal traces of a powdery substance consistent with the materials, including plaster, that would have been used for a life mask. His balding pate and aged features were also exaggerated through the use of harsh lighting and a slightly raised viewpoint that hides the artist's eyes behind a pair of tinted, reflective glasses. Isolated in the center of the photograph, against a dark background that lends an unreal remoteness to his pale, plaster-flecked features, Duchamp, who was fifty-eight at the time, looks nearly thirty years older, hence the title's inversion of his age.

Fig. 2.3

Percy Rainford (American, 1901-1976)

Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85. For View, March 1945

Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 2.4

Percy Rainford

Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85, 1945

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- The Duchamp issue of View was the most ambitious, elaborate, and expensive number of the magazine, which ran from 1940 to 1947 and was dedicated to the Surrealist cause.[7] The issue also included a complex, six-page spread designed by Frederick Kiesler in close collaboration with Duchamp. This carefully orchestrated photomontage, entitled Les Larves d'imagie d'Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp (The Larval Images of Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp), was comprised of a tripartite assembly of photographs of the artist in his Fourteenth Street studio, surrounded by a cluttered array of papers, tools, and supplies, many of which he would put to use in the following year when he began work on preliminary studies for Étant donnés (fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5

Frederick Kiesler (American, born Ukraine, 1890-1965)

Les Larves d΄imagie d΄Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp (The Larval lmages of Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp), published in View, March 1945

Photomontage, 23 × 30,5 cm (91⁄16 × 12 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950-134-1061

---- Two of the six pages of the 1945 View triptych are bound at their outer edges, so that the entire piece, when opened at the center, reveals a three-panel spread. A section of the third page, the right panel of the triptych, is cut away at the top to reveal an advertisement for Pierre Matisse's gallery in New York, while the two outer pages also have cutout flaps at their centers, which the reader is directed to fold inward. The left flap has a small tab that is inserted into a corresponding slot on the right flap. When assembled, the episodic series that makes up the triptych forms a composite image of Duchamp's Large Glass (see FIG. 2b.1), which Kiesler had earlier extolled as "the first x-ray painting of space."[8] The triptych thus continued the interest Kiesler shared with Duchamp in the interactive role of the spectator in completing the work of art, in this case achieved by maneuvering the flaps to form an image of the artist's magnum opus.[9] Duchamp must have been impressed by Kiesler's remarkable photocollage — which combined images of the artist and his studio with aerial photographs of crowds and automobile traffic — since he would redeploy the architect-theorist's working methods in his studies for the landscape backdrop of Étant donnés. In both the 1946 photocollage landscape (FIG. 2a.1) and the landscape collage on plywood that he completed in the following decade (FIG. 2a.2), Duchamp created an apparently seamless image of the hillside and trees with cut-and-pasted, spliced-together photographs, as determined by technical examination (see Beth A. Price, Ken Sutherland, Scott Homolka, and Elena Torok, "Evolution of the Landscape: The Materials and Methods of Étant donnés Backdrop" in Michael R. Taylor; "Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés," Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 264-66).

FIG. 2b.1

Marcel Duchamp

La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même

(The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even) (The Large Glass), 1915-23

Oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels

277.5 × 175.9 cm (1091⁄4 × 691⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952-98-1

FIG. 2a.1

Marcel Duchamp

Untitled - photocollage landscape study for

Étant donnés: 1° la chute d΄eau, 2° le gaz d΄éclairage, c. 1946

Textured wax, pencil, and ink on tan paper and cut gelatin silver photographs,

mounted on board 43,2 × 31,1 cm (17 × 121⁄4 inches)

Private collection

FIG. 2a.2

Marcel Duchamp

Landscape collage on plywood - study for landscape backdrop of

Étant donnés: 1° la chute d΄eau, 2° le gaz d΄éclairage, 1959

Collage of cut gelatin silver photographs over paper, with paint,

graphite, crayon, ballpoint-pen ink, and adhesive on

plywood panel, with pressure-sensitive tape

67 × 99,4 cm (263⁄8 × 391⁄8 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mme Marcel Duchamp

---- The View triptych was composed in part from images taken by Percy Rainford, an African-American freelance photographer who specialized in interior scenes and images of works of art. Duchamp was photographed in his studio during the course of two sessions, on January 1 and January 11, 1945. Kiesler later praised Rainford for his refusal to lower his standards by adopting inferior modern cameras: "... in the era of the slick-clicking Leica, [Rainford] works with a big hatbox of a camera, the type you see only in posters or in Luna Parks [sic]."[10] Rainford's old-fashioned equipment perfectly captured the atmosphere of Duchamp's studio in black-and-white photographs that Kiesler cut up and spliced together to form the triptych, which was dedicated to "H(ieronymous) Duchamp."

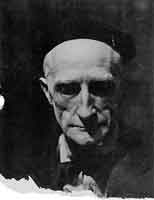

---- This ambiguous inscription has been widely understood as a reference to the Netherlandish painter Hieronymous Bosch, whose esoteric imagery has been linked to a heretical sect called the Adamites, which advocated free love and nudity in worship.[11] The Surrealists had long admired the hermetic symbolism and profusion of sensuous and psychologically disturbing images found in Bosch's dreamlike triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1500-1505; fig. 2.6), which predicted a new spiritual paradise through the return to a primal state of innocence, and they identified Bosch's scene as a powerful precursor to the utopian vision, mystic reverie, and free-spirited dissent of the Surrealist artist in modern society, whose work similarly challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and other forms of organized religion.

Fig. 2.6

Hieronymous Bosch (Netherlandish, c. 1450-1516)

The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1500-1505

Oil on wood panels. 220 × 389 cm (865⁄8 × 1531⁄16 inches)

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Patrimonio Nacional

---- Kiesler also may have replaced "Marcel" with "H(ieronymous)" as a reference to Duchamp's full name — he was born Henri Robert Marcel Duchampas — well as his covert activities in his studio-cell. Given that Jerome is the anglicized form of Hieronymous, Kiesler may have intended his dedication to suggest that Duchamp's underground existence mirrored that of the Christian scholar Saint Jerome in his study. Indeed, Antonello da Messina's celebrated painting Saint Jerome in His Study (c. 1475; fig. 2.7) appears to have supplied Kiesler with the tripartite construction of the photomontage, as well as much of its content and meaning. That Duchamp was aware of, and even complicit in, this artistic appropriation is evidenced by Rainford's photograph of the artist in the center of the View triptych—where Duchamp clearly emulates the studious, meditative pose of Messina's Saint Jerome, whose far-off gaze suggests that he is lost in thought—as well as the complex architectural environment.

Fig. 2.7

Antonella da Messina (Italian, c. 1430-1479)

Saint Jerome in His Study, c. 1475

Oil on lime panel, 45,7 × 36,2 cm (18×141⁄4 inches)

The National Gallery of Art, London. Bought 1894

---- Like Duchamp, Jerome is depicted in profile, and the shelves of his study chamber are lined with objects and paraphernalia that have a coded meaning decipherable only on close examination. As several scholars, most notably Linda Dalrymple Hendeŕson, have pointed out, the View triptych contains numerous references to earlier works by Duchamp, especially The Large Glass.[12] An overlaid image of the latter, which hovers like an apparition over the seated artist in the central panel, came from a photograph by Berenice Abbott, taken in January 1937 to accompany an article by Kiesler on Duchamp that was published in May of that year in the Architectural Record.[13] This is one of three images of Duchamp's works that were included in the foldout triptych, along with Fresh Widow (1920) and La Bagarre d'Austerlitz (The Brawl at Austerlitz; 1921). Other works by the artist were alluded to through disguised symbolism, such as hidden associations with the materials used in their construction. According to Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "various objects around Duchamp's table were transformed by Kiesler's magic wand into elements of the Large Glass: two saws, a lamp and cords hanging from the ceiling become the pendu femelle; film spools change to the Water Mill, and the ribbons of film to the Glider; [and] a chair leg turns miraculously into the Louis XV chassis of the Chocolate Grinder."[14]

---- When seen in conjunction with Saint Jerome in His Study, the choice and position of these works no longer appear random, and it is clear that they were instead determined by the architectural configuration of the original painting by Messina, where the saint's carrel is set within a large stone-vaulted building with bipartite windows on the upper level. The placement of these windows corresponds to that of the dramatically lit rectangular shapes of the draft pistons in the Milky Way of The Large Glass, situated above Duchamp's head in the photomontage, while the position of the lower-story windows to the right and left of Saint Jerome corresponds to that of Fresh Widow and The Brawl at Austerlitz.

---- It may well have been Duchamp who drew Kiesler's attention to Saint Jerome in His Study, especially given his public and private pronouncements, in interviews as well as in his letters to Maria Martins, that artists should lead an ascetic "underground" existence, working in solitude and with a minimum of distractions. These sentiments evoke Jerome's life as a hermit in the wilderness, and it is therefore tempting to connect Messina's painting with Étant donnés, a work that Duchamp would begin to construct the following year. Indeed, Étant donnés recalls Saint Jerome in His Study in its use of a high degree of artifice to present a range of disparate objects and animate forms coexisting in a seemingly spacious three-dimensional environment.

---- Messina's painting, like the View photomontage, is divided into distinct compartments that impose a strict architectural order that counters the verisimilitude of the natural elements of the composition, such as the strutting peacock and the basin of water in the foreground.[15] The parallels between Messina's painting of Saint Jerome and the photomontage further suggest that in Duchamp's letters to Martins some of his coded references to secular convents and monasteries, and perhaps even the title "Our Lady of Desires," can partially be understood as parodying the teachings of Jerome and his letters. to Eustochium, which outlined the ascetic manner of life.

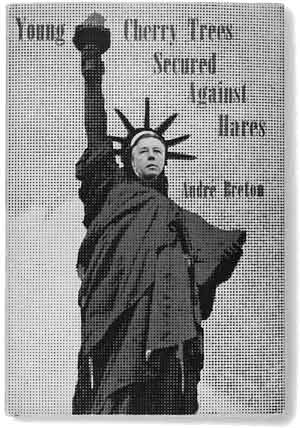

FIG. 2a.3

Marcel Duchamp

Cover design for André Breton΄s Young Cherry Trees Secured against Hares

1946 (New York: View Editions)

Hardbound book with paper cover, 23,8 × 16,2 cm (93⁄8 × 63⁄8 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of an anonymous donor

---- In the following year, Duchamp designed a montage for the dust jacket and cover of Breton's short anthology of poems entitled Young Cherry Trees Secured against Hares (Jeunes cerisiers garantis contre les lièvres; FIG. 2a.3). The dust jacket contains an image of the torch-bearing woman of the Statue of Liberty, the famous emblem of Franco-American exchange, while a photograph of Breton graces the inside cover. A hole has been cut in the position of the face of the Statue of Liberty so that Breton's features show through, much like the placard that once stood outside the entrance to what is now the Museum of Immigration by the statue's plinth, and that bore a painted image of the statue through which visitors could poke their heads and purchase a snapshot of themselves.[16] Duchamp's open-ended work sends an ambiguous message that can be read on many levels. In the broadest terms, the design can be viewed as a tribute to Breton's defense of French culture and liberty during World War II. Alternatively, Duchamp's earlier creation of his lascivious Rrose Sélavy alter ego suggests that the image lampoons Breton's infamous homophobia by presenting the writer as a cross-dressing drag — queen perhaps as a private joke with Charles Henri Ford, the editor of View and publisher of Young Cherry Trees Secured against Hares, who was openly gay and had earlier mocked the imperious writer as "Miss Breton" for his long hair and "velvet silk stockings."[17] That Duchamp may have satirized his friend in this work is supported by the fact that Breton's overbearing and authoritarian personality often tested his patience to its limit. In a letter to Maria Martins dated May 24, 1949, the artist stated, "André can be really very vulgar at times and his Hitlerite attitude is often synonymous with imbecility."[18]

---- Despite objections from some of Breton's friends, who recognized the strong undercurrent of transvestitism,[19] the writer used Duchamp's see-through design as the cover for his book of poems, and identified his depiction as an allegorical symbol of "liberty enlightening the world" (in the words of the statue's original title). It is also possible that the image references the Surrealist leader's essay "Lighthouse of the Bride," recently translated and reprinted in the Duchamp issue of View, in which Breton celebrated The Large Glass as a beacon of salvation for a drowning modern civilization. Duchamp's cover design thus suggests that the "luminously erect" Breton would assume the role his essay designated for The Large Glass, and guide "future ships on a civilization which is ending."[20] Certainly, as an image of a woman holding a burning torch, the design for the cover and dust jacket is of intrinsic interest with regard to the complex genesis of the Étant donnés mannequin, which may have inspired Duchamp to choose the Statue of Liberty as a source.

ÉTANT DONNÉS: MARIA

It is perhaps no coincidence that Duchamp began work on the mannequin's construction shortly after the end of World War II, when his short yet intense engagement with members of the Surrealist group during their exile in New York effectively was brought to a close. Following the group's return to Europe, Duchamp had - more time to devote to the secret Étant donnés project. According to the Surrealist artist Enrico Donati, Duchamp's relationship with Maria Martins had become increasingly serious by the mid-1940s:

She was madly in love with Duchamp. Everything Marcel said, she went "ahhh" ... you know. She clearly adored Marcel, and he was falling for her too, although he would never come out and say it. I certainly noticed a change in him around 1946 and '47, when we worked together on a number of projects, even signing them together. At that time, Marcel became very close to me, and I became close to him, to such a degree that I can say today that he was my bastard father and I was his, bastard son. I felt I knew him better than anyone else, but we never discussed things like love. I can tell you that Maria was Brazilian, very beautiful, and full of life. Marcel had never met anyone like her and she certainly had a deep impact on him. I think he was excited by their affair, but he also had an independent streak. He loved secrecy and being alone, so there was always going to be some unhappiness there.[21]

---- By 1946, the year that the artist began work on the Étant donnés mannequin, Martins publicly espoused Duchamp's view that great art is possible only by working "underground," thus confirming the profound effect that his ideas were having on her own work. "Art is the underground of the world," she explained to a reporter from Time magazine, "and we will win in the end."[22] Duchamp's burgeoning relationship with Martins persuaded him to use her body to make plaster casts and drawings for the mannequin, employing the techniques he had learned from Ettore Salvatore. The artist's inscription on a preliminary sketch (FIG. 2a.4) confirms the central role she played in the assembly and meaning of the work from its inception: "Étant donnés: Maria, la chute d'eau et le gaz d'éclairage / Marcel Duchamp / Dec. 47."

FIG. 2a.4

Marcel Duchamp

Étant donnés: Maria, la chute d΄eau, et le gaz d΄éclairage, 1946

Pencil on paper

40 × 29 cm (153⁄4 × 117⁄16 inches)

Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Gift, 1985, dedicated to Ulf Linde from Tomas Fischer

---- This delicate pencil drawing of Martins's nude body establishes the position of the nude mannequin in the completed assemblage: Her strained leg and abdominal muscles, which Duchamp expertly rendered through graphite shading, give the impression that she is standing on one leg while raising the other. This pose, suggestive of erotic images of cunnilingus or urination, would have been hard for Martins to sustain without the support of a chair. Indeed, the position of her outstretched left foot in Duchamp's drawing suggests that at one point it rested on a flat surface, like the chair that supports the model's weight in Balthus's 1933 painting Alice (Alice in the Mirror), where the woman's pose also serves to part her labia (fig. 2.8).

Fig. 2.8

Balthus (Balthasar Kłossowski de Rola; French, 1908-2001)

Alice (Alice in the Mirror), 1933

Oil on canvas, 162,3 × 112 cm (637⁄8 × 441⁄8 inches)

Musée National d΄Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1995

---- The December 1947 date of Duchamp's inscription on this pencil drawing, now owned by the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, has puzzled scholars, since the work has long been considered the first study for Étant donnés, which the artist himself dated 1946-66 on the right arm of the mannequin in the final work (see FIG. 2b.2). In a 1969 letter to Evan H. Turner, at that time the Director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Maria Martins confirmed that this drawing was the earliest known work directly related to Étant donnés.[23] Duchamp does mention making a drawing of "the woman (in pencil)" in a letter to Martins dated September 6, 1948, but this now-lost sketch appears to have been made after he had begun work on the construction of the nude, since the same letter also contains references to the mannequin's "skin under its steel rods."[24] My own belief is that the preliminary drawing in Stockholm was made in 1946 and presented to Martins in December 1947, perhaps as a Christmas present, a dating supported by another drawing that Duchamp enclosed in the Boîte-en-valise that he gave to the Surrealist artist Enrico Donati (FIG. 2a.5). This pencil drawing, which delicately renders Martins's right foot on a piece of torn paper, is signed and dated 1946, and almost certainly was made in the same year as the preliminary sketch of her full body. The inscription on the latter also suggests a variant title for the tableau-construction, which may have been changed to its current wording — in which the name Maria has been expunged — following the end of Duchamp's affair with Martins and the beginning of his new relationship with Teeny Matisse in the fall of 1951.

FIG. 2b.2

Marcel Duchamp. Polaroid photograph of the right arm of the mannequin, showing the title, date, and artist΄s signature, from the Manual of Instructions, 1966.

![Marcel Duchamp, Untitled (drawing of a foot), 1946 Marcel Duchamp - Untitled (drawing of a foot), 1946 - Original drawing from an unnumbered edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise) (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in a Valise]) - Pencil on paper](41/Fa-5-Marcel-Duchamp-Untitled-drawing-of-a-foot.jpg)

FIG. 2a.5

Marcel Duchamp

Untitled (drawing of a foot), 1946

Original drawing from an unnumbered edition of De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise) (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in a Valise])

Pencil on paper

17,1 × 18,4 cm (63⁄4 × 71⁄4 inches)

Private collection, New York

---- Duchamp used this preliminary drawing as the basis of an undated photocollage study for Étant donnés in which Martins's nude torso is placed within a landscape environment, complete with a waterfall, and framed on three sides by a blue paper border (FIG. 2a.1). Her taut, muscular body was rendered in black ink on tan-colored paper that was then covered with textured wax to give it a three-dimensional quality. Once again, Martins appears to stand rather than recline, here in lush surroundings created from fragments of a series of waterfall photographs that Duchamp had taken in Switzerland in August 1946.

FIG. 2a.6

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.7

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.8

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.9

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, copy print after 1946 original, printed c. 1973*

Gelatin silver print - 18,9 × 19,2 cm (77⁄16 × 79⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.10

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.11

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

FIG. 2a.12

(detail)

Marcel Duchamp

Swiss Landscape with Waterfall, 1946

Gelatin silver prints - 18,1 × 17,1 cm (71⁄8 × 63⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Anne d΄Harnoncourt Records

---- Duchamp took seven photographs of a waterfall at Bellevue (FIG. 2a.6 - 2a.12), a small hamlet near Chexbres, Switzerland, during a vacation with Mary Reynolds that lasted from July 30 to September 2, 1946. After staying in Bern at the residence of the French ambassador Henri Hoppenot (whose daughter, Violaine, had served alongside Reynolds in the French Resistance during the war), the couple spent four days, August 5-9, in the small village of Bellevue on the advice of the ambassador's wife, Hélène, who had visited there as a child.[25] Hélène thought they might enjoy the spectacular panoramic view of Lake Geneva and the surrounding mountains of Vaud, Valais, and Savoy, as well as the Jura Hills, visible from a spot known locally as the Balcon du Monde (Balcony of the World), which had inspired several earlier artists, including Gustave Courbet, Ferdinand Hodler, and Felix Vallatton, to depict the natural beauty of the lake and the mountains in the far distance.[26] What impressed Duchamp, however, was the picturesque waterfall that cascaded down the steep, rocky slopes, terraced with vines, between Chexbres and the neighboring village of Puidoux.

---- At some point during his stay in Bellevue, Duchamp captured different viewpoints of the noisy, gushing Le Forestay waterfall (fig. 2.9) in seven photographs, six of which are in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, while one is lost and known only through a copy print. These photographs were taken from a zigzagging path beneath the Hotel Bellevue (and separated from it by a winding road), where Duchamp and Reynolds were staying, and facing a former walnut oil-processing facility (the French word huilerie is visible on the building's façade in two of the photographs). The rooftop of a pistol-shooting range appears in the foreground of several of the images, and perhaps was associated in the artist's mind with the nine shots of The Large Glass. It also should be pointed out that the oil-processing facility was powered by a water mill, another key element of The Large Glass. The combination of the waterfall, water mill, and shooting range may explain why Duchamp was so powerfully drawn to this site after discovering it by chance in August 1946.

Fig. 2.9

Le Forestay waterfall, Bellevue, Switzerland, as it appears today

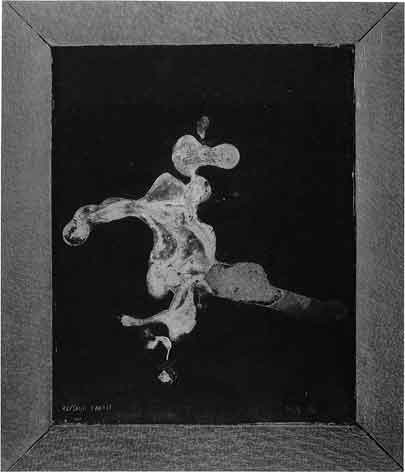

---- The artist's various vantage points allowed him to capture the enchanting effect of the flowing water and its arboreal surroundings. The oil-processing building can be seen clearly on the left-hand side of the photocollage study behind Martins's nude torso, but later would be edited out of the landscape backdrop of Étant donnés, as Duchamp chose to concentrate instead on the trees and foliage to either side of the deep ravine down which the waterfall precipitously plummeted. One of the most striking features of this small-scale preliminary study is the photocollage of the tall poplar tree that stands in front of, and partially obscures, Martins's raised thigh and extended arm, and that also appears in the final landscape backdrop of Étant donnés. This tree, with its roughly serrated, curled edges, was cut out from a print of one of the photographs taken at Bellevue, and confirms the artist's interest in manipulating the landscape to fit his composition. That Duchamp was thinking about the landscape environment of Étant donnés in 1946 is suggested by another "seminal" work he gave to Martins, Paysage fautif (FIG. 2a.13), in which accumulated semen has dried into amorphous blobs to form a "wayward," or "faulty," landscape, and whose title also may refer to the strange, artificial nature of the photocollage landscape that Duchamp constructed from cut-and-pasted photographic fragments.

FIG. 2a.13

Marcel Duchamp

Paysage fautif (Wayward of Faulty Landscape), 1946

Original painting from the deluxe edition of

De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-svalise)

(From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [The Box in a Valise]), no. XII/XX

Seminal fluid on Astralon backed with black satin, 21 × 16,5 cm (81⁄4 × 61⁄2 inches)

The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama, Japan

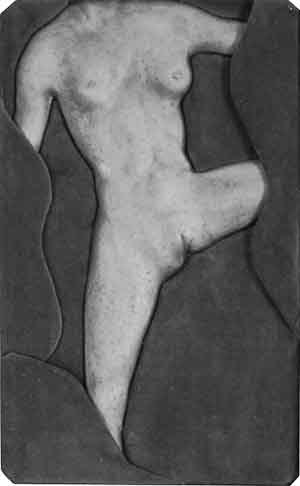

FIG. 2a.14

Marcel Duchamp

Study for Étant donnés: 1° la chute d΄eau, 2° le gaz d΄éclairage, c. 1946-48

Pigment and graphite on leather over plaster with velvet

50,2 × 31,1 cm (193⁄4 × 121⁄4 inches)

Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Gift, 1985, dedicated to Ulf Linde from Tomas Fischer

---- The third preliminary study (FIG. 2a.14) for Étant donnés is signed and dated 1948-49 but, like the two previously discussed works, may have been made earlier, during a period of intense creativity following Duchamp's return to his New York studio in the fall of 1946 with the photographs that he had taken on vacation with Mary Reynolds in Switzerland. This work consists of a smaller-than-life-size plaster figure probably based on Maria Martins's torso, which Duchamp covered in leather and surrounded with velvet. Hugh Shaw, an editor and designer who worked for the Arts Council of Great Britain and helped the British artist Richard Hamilton organize the 1966 Duchamp retrospective exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London, recalled a conversation with Duchamp during which the latter stated that this study was made in 1946,[27] contradicting the misleading double date in his hand-written inscription in ink on the wood-panel verso of the work: "Cette dame appartient à Maria Martins / avec toutes mes affections / Marcel Duchamp 1948-49" (This lady is owned by Maria Martins / with all my affection / Marcel Duchamp 1948-49). The inscribed date suggests that Duchamp gave the work to the Paris-based Martins, presumably as a 1948 Christmas gift that was presented to her when they next saw each other in the following year. The artist's lengthy inscription also contained instructions in French for lighting the piece, as well as information regarding the fragility of the mine de plomb (graphite drawing stick) that he used to exacerbate the shadows of her speckled skin.[28]

---- This third preliminary study for Étant donnés removes the landscape background of the 1946 photocollage to focus exclusively on Martins's nude torso. As discussed by Meighan,[28-a] Duchamp first rendered the torso in plaster and then cove red it in leather, which was highlighted with a graphite drawing stick to add depth and definition to her muscular frame. The truncated figure was then imbedded in a green-brown velvet support and partially enveloped within curvilinear folds of the same velvet material, which denote the terminus of each limb. While the right forearm, lower right leg, and right foot of the Étant donnés mannequin would not be visible from the peepholes, and thus were left similarly truncated, it was necessary to cast separately the bent left leg and the left forearm and hand that holds aloft the lamp, and attach them at the same points where the velvet folds intersect with those limbs in the study. The leather that Duchamp used in the study may have been acquired in Europe, possibly through Mary Reynolds around the time of their 1946 vacation in Switzerland, since she used leather, vellum, and other animal skins in her bookbinding. If so, the use of leather would imbue this work with references to Reynolds as well as Martins.

---- The use of materials with highly personal meaning is entirely in keeping with Duchamp's working methods, especially in the Étant donnés project, which was assembled with carefully chosen materials and objects that frequently make reference to earlier works and ideas, as well as to the women with whom he was romantically involved. However, the use of leather in the third study may indicate a post-1946 date for the work, since Duchamp made his first known reference to the use of skin in a letter to Martins dated July 11, 1947: "The skin is in the press until tomorrow morning. When it is wet and taut it looks like fine-quality marble but I fear that in drying it will yellow."[29] In a subsequent letter dated September 6, 1948, Duchamp informed her that he would return to his studio the next day to examine "my dry skin under its steel rods."[30] Since the artist would not complete the full-scale version of the female nude until May 1949, one may reasonably assume that he was referring in these two letters to the leather-over-plaster figure, which thus perhaps should be dated between 1946 and 1948.

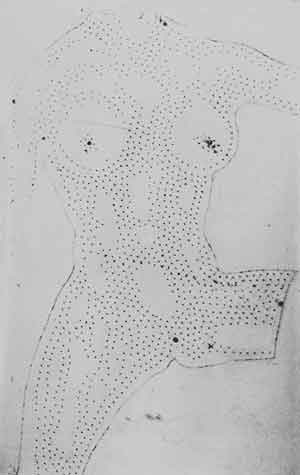

---- The series of evenly spaced pockmarks shaded with mine de plomb that Duchamp referred to in his inscription have long perplexed scholars of the artist's work. Spaced at regular intervals, these small concave depressions in the skin may have been used by Duchamp to transfer the coordinates of the figure from the preliminary 1946 drawing (FIG. 2a.4) to the leather-over-plaster figure (FIG. 2a.14). This idea is supported by the existence of another, slightly larger image of the nude's torso that was outlined in gouache on a sheet of transparent Plexiglas, which the artist then perforated with a large number of drilled holes (FIG. 2a.15). Thought to have been made around 1950, although the exact date remains unknown, this translucent sheet appears to have been used as a measuring device or working tool in which the position of the pierced holes helped to determine the form of the Étant donnés mannequin's body.

FIG. 2a.15

Marcel Duchamp

Preparatory study for the figure in Étant donnés:

1° la chute d΄eau, 2° le gaz d΄éclairage, c. 1950

Gouache on transparent perforated Plexiglas

91,4 × 55,9 cm (36 × 22 inches)

Private collection

---- Another work related to Étant donnés, which Duchamp made in 1946 and placed in the Boîte-en-valise he gave to the artist Roberto Matta, included samples of head, axillary, and pubic hair that were taped to a piece of paper that was then mounted on the reverse of a piece of Plexiglas. Duchamp linked the individual, taped-down clumps of red and brown head and body hair through a series of pencil markings that formed a rudimentary torso. This figure can be identified as male by the hand-drawn image of an ejaculating penis that emerges from the mass of mixed red and brown pubic hair at the bottom of the sheet. Since the artist was a redhead and Martins a brunette, this tangle of red and brown hairs most likely came from their heads and bodies, although DNA analysis would provide a definitive attribution.

---- According to the artist's first wife, Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, Duchamp "had an almost pathological horror of anything that resembled hair," and she complied with his request to shave her armpits and pubic region.[31] Duchamp's phobia may explain why the Étant donnés mannequin's vulva is hairless. However, a more likely reason for the nude's lack of pubic hair was the bodycasting process, which required the removal of Martins's hair — still visible in the first study for Étant donnés, thus supporting a 1946 dating for this work. Denise Browne Hare, who photographed the artist's Eleventh Street studio after his death, recalled finding plastic envelopes filled with pubic and axillary hair, presumably belonging to Martins and dating to the time of her body casts.[32] The fact that similar body hair was used to create the drawing in Matta's Boîte-en-valise that the artist had begun to create casts of Martins's newly shaved body as early as 1946, using the techniques that he had learned in his private lessons with Ettore Salvatore, which enabled him to cast individual body parts, such as breasts, arms, and legs, and splice them together to form a seamless torso.[33]

PLEASE TOUCH

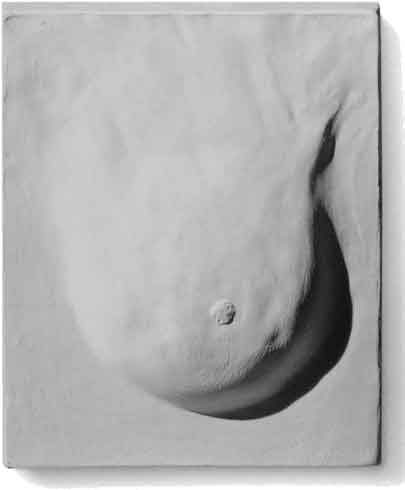

A cast of Martins's left breast (FIG. 2a.16) served as the model for the cover of the deluxe edition of the exhibition catalogue for Le Surréalisme en 1947, published on the occasion of the 1947 Exposition Intemationale du Surréalisme, which opened on July 7 at the Galerie Maeght at 13 rue de Téhéran in Paris. Co-organized by Duchamp and André Breton, the exhibition was dedicated to the theme of "modern myths," a familiar subject for the Surrealists both during and after World War II as they sought to reinvent and reinvigorate the group's activities in the changing postwar cultural landscape, in which they were increasingly isolated and often associated exclusively with the avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s. Le Surréalisme en 1947 was an attempt to cement the collective efforts of the Surrealist artists and writers led by Duchamp and Breton, and to discover new myths rather than perpetuate what they perceived as outmoded ideologies.[34]

FIG. 2a.16

Marcel Duchamp

Study for Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947, Plaster

21,9 × 18,1 cm (85⁄8 × 71⁄8 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Enrico Donati

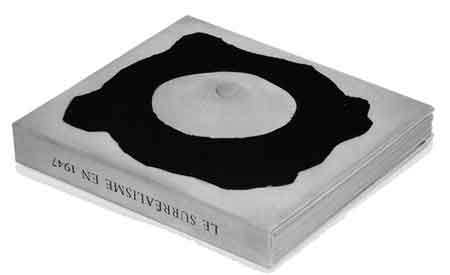

---- Duchamp's original idea for the catalogue, which was limited to 999 copies, was to carve the breast in shallow relief in carefully prepared rectangular blocks of plaster, affixing a small nipple at the end by using a tiny amount of leftover plaster that he rolled between his thumb and forefinger; the entire block would then be mounted in a deeply recessed book cover. The artist produced two prototypes of this laborious plaster edition in June 1947, before Enrico Donati persuaded him to reconsider his time-consuming approach to the project, since the publisher required nearly a thousand covers under a relatively tight deadline. Donati's solution was to purchase a large number of foam-rubber "falsies," after discovering one in a store near his studio, which both artists then hand-colored in May 1947:

At that time, my studio was in a tall building at 200 West Fifty-seventh Street, across the street from Carnegie Hall, and I knew that between Fifty-fifth and Fifty-sixth Street on Seventh Avenue there was a shop selling all sorts of bras, ladies' bras, and underwear and things like that. So I went there and found this falsie, which I thought would make a terrific cover if we could flatten it down. So I buy a sample to show Marcel, and asked the lady of the shop for the name of the supplier. She was very nice, quiet. Couldn't care less what I needed them for. So she gives me the name of somebody who was making these bosoms in a factory in Brooklyn. Marcel gave me the go-ahead. He liked the idea right away and thought the falsie looked great. So I had them mold for me the 999 bosoms for a couple of bucks apiece. It was a lot of money and we never got paid. Anyway, they delivered the falsies to my studio in boxes, and then Marcel and I started to paint each bosom on the floor, using oil paint and Conte crayon, which we rubbed on the nipples with our fingers. When I finished the first one, I said to Marcel in English, "Please touch," to which he replied, "Prière de toucher," in French, and then we knew we had the title for the book. From that moment, the two of us are sitting on the floor painting nearly a thousand bosoms. Do you realize how long that took? We worked for days and nights and days and nights until we finished the damned job. It was enough to drive us insane. When we were finished, I told Marcel that I never thought I would get tired of handling so many breasts, and he replied, "Maybe that's the whole idea."[35]

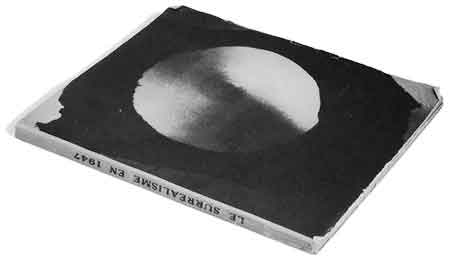

---- Once the. falsies had been colored, they were mounted on irregularly shaped fragments of black velvet, giving the cover design for the deluxe edition the appearance of an exposed breast peeking through the fabric of a black evening dress (FIG. 2a.17). For the cover of the standard edition of the catalogue, the French Surrealist artist Rémy Duval made a literal representation of the deluxe book cover by photographing a real woman's conical breast surrounded by a velvet support (FIG. 2a.18). Another photograph by Duval, depicting a three-quarters view of the same woman's velvet-collared breast, was included in the boxed set of the deluxe edition of the catalogue (fig. 2.10). In 1947, Man Ray also made a photograph of a female breast, taken from the same frontal viewpoint as Duval's cover image but based on Duchamp's breast-collage cover rather than a real woman (FIG. 2a.19).

FIG. 2a.17

Marcel Duchamp and Enrico Donati (American, born Italy, 1909-2008)

Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947

Numbered edition of exhibition catalogue for Le Surréalisme en 1947 (Paris: Pierre à Feu/Maeght)

Bound book with collage of foam rubber, pigment, velvet, and cardboard, adhered to removable cover - 23,5 × 20,5 cm (91⁄4 × 81⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the Gertrud A. White Memorial Fund

FIG. 2a.18

Marcel Duchamp

Cover design for Le Surréalisme en 1947, 1947

Paperbound exhibition catalogue with cover photograph by

Rémy Duval (Paris: Pierre à Feu/Maeght)

24,3 × 20,8 cm (99⁄16 × 83⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

Fig. 2.10

Rémy Duval (French, 1901-1984)

Photograph of a breast surrounded by a velvet collar, used in the fabrication of Duchamp and Donati΄s Priere de loucher (Please Touch), c. 1947

FIG. 2a.19

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947

Gelatin silver print

24,1 × 19,7 cm (91⁄2 × 73⁄4 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul, and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother, Alexina Duchamp

---- The tactile quality of the foam-rubber breast was alluded to in the catalogue's title, Prière de toucher (Please Touch), which Duchamp and Donati printed on a sticker affixed to the back of the book. The public thus was invited not only to look but also to touch the breast and its hand-tinted pink nipple, which resembled a doorbell or the bull's eye of a target — the target being, of course, the strict rules imposed by museums and art galleries that instruct visitors, "please look, but do not touch." The subversive nature of the design, with its playful mingling of the body and the visual, was also established by a series of photographs taken at the exhibition by an anonymous photographer, in which a blindfolded nude woman covers her crotch with Duchamp and Donati's foam-rubber breast and its squared-off fragment of black velvet (fig. 2.11). These images tacitly acknowledge the book cover's playful use of displaced body parts to "corporealize the visual," which, as art historian Rosalind Krauss has demonstrated, countered the notion of "pure" opticality that was so central to the aesthetic tenets of mainstream modernism.[36]

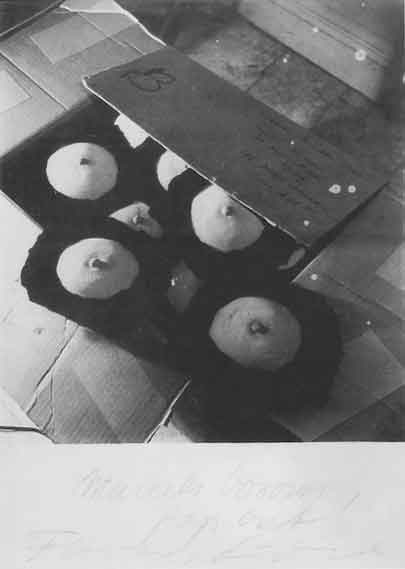

Fig. 2.11

Totem of All Religions, conceived and designed by Frederick Kiesler,

executed by Henri Étienne-Martin (French, 1913-1985), with model, in the Hall of Superstitions, Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, Galerie Maeght, Paris, 1947

---- Donati gleefully recalled that tile breasts took on a life of their own in his studio, when they were piled up in cardboard boxes awaiting shipment to Paris: "One time, I only left the room for a second before the lid came off with all the pressure, and the bosoms started to fly up to the ceiling."[37] The aftermath of a similar explosion of flying breasts was captured in a previously unpublished photograph taken by Denise Bellon in Paris shortly after the shipment of boxes arrived, leading Frederick Kiesler to give it the hilarious label Marcel's Bosoms Pop Out! (FIG. 2a.20). Indeed, the breasts popped out with such regularity that Duchamp dubbed them seins vivant (living breasts), and warned his Surrealist friends in France to have a camera at the ready when tile shipment of breast-covers arrived in Marseilles. Sure enough, an unwitting customs officer opened the crate they were traveling in, thus releasing the breasts, which had been compressed inside the crate like a coiled spring: "Those goddamn bosoms popped out like a jack-in -the -box," remembered Donati. "They flew up in the air, and then landed all over the dock, with everyone laughing and loving every second of it."[38]

FIG. 2a.20

Denise Bellon (French, 1902-1999)

Marcel΄s Bosoms Pop Out! 1947

Gelatin silver print mounted on cardboard, with inscription in pencil by Frederick Kiesler

17,8 × 12,7 cm (7 × 5 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Marcel Duchamp Research Collection,

Kiesler Research Material

---- The 1947 Surrealist exhibition provided another public opportunity for Duchamp to test out his latest ideas concerning the Étant donnés project. Because he planned to leave Paris before the installation of the show, he entrusted his plans for the Salle de Superstitions (Hall of Superstitions) to Kiesler, who also executed one of Duchamp's exhibition entries, entitled Le Rayon vert (The Green Ray), while Le Soigneur de gravité (The juggler of Gravity) was constructed by Roberto Matta according to the artist's instructions.[39] As we have discussed, Duchamp and Kiesler held similar ideas on exhibition design and the nature of visual perception, including the ideal viewing position for a work of art, which both men believed should be determined by the artist or designer, rather than the spectator. One of the key concepts of Breton and Duchamp's design for the exhibition Le Surréalisme en 1947 was that progress through the successive spaces would correspond with what the Surrealist leader described in me catalogue as "initiatory" settings. The seeker of knowledge, in this case the visitor, would be presented with a series of tasks or ordeals to overcome, thus inducing his or her mind to "dwell on the disturbing and extraordinary aspects throughout the ages of certain individual and collective types of behavior."[40]

---- Before departing for the United States, Duchamp left behind some initial ideas for the installation in accordance with the notion of an exhibition environment that would unfold as a cycle of tasks and initiations into the mysteries of Surrealism. As the Surrealist artist and historian Marcel Jean recollected, Duchamp "imagined the hall of Superstitions as a white grotto and proposed that the effect should be produced by stretching an immaculate fabric on some suitable framework; he also drew up plans for the Labyrinth, and for the Rain hall, in which he recommended that a billiard table should be installed — one of the rare notes of deliberate humour in the exhibition."[41]

---- A polymath artist-architect whose work sought to redefine the relationship between art and viewer through creative installation techniques, Kiesler was well qualified to expand on Duchamp's ideas for a fluid, unnerving, and disorienting architectural environment in which to display the entries by the eighty-seven participating artists, representing twenty-four countries.[42] The initial plan, which was left unrealized, was that the exhibition would begin with a room devoted to "Surrealists Despite Themselves," to have included works by Arcimboldo, Hieronymous Bosch, William Blake, and Lewis Carroll, as well as by more recent artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, André Masson, and Pablo Picasso, "who had ceased to gravitate in the movement's orbit."[43] In Kiesler's fully realized final design, the visitor entered the exhibition by ascending a red staircase of twenty-one steps, signifying all but one of the Major Arcana of tarot cards, which are numbered from zero to twenty-one. The steps were designed after the spines of occult and mystical books, such as Emanuel Swedenborg's Memorabilia and Sir James George Frazer's Golden Bough, which together indicated the "degrees of ideal knowledge."[44]

---- Having reached the top of the stairs, viewers donned white hoods designed by Joan Miró and entered the Hall of Superstitions, a dramatic, multipart environment in the shape of an egg, which Kiesler believed would "cure man of his anguish" by unleashing and satisfying his psychic need for ritual and superstition (fig. 2.16).[45] This central exhibition space displayed recent works by Julio De Diego, Enrico Donati, Max Ernst, David Hare, Roberto Matta, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy, which the architect-theorist installed on the floors, ceilings, and curtained walls of the Galerie Maeght's oval-shaped entranceway. Miró's long, scroll-like painting Cascade of Superstitions, described by Kiesler in the exhibition catalogue as "the frozen cascade of superstition," was mounted vertically on a curved wall, where it flowed like a waterfall of hieroglyphic signs from the ceiling to the floor.[46] There it met Ernst's Black Lake, painted on the floor, which Kiesler viewed as "a feeding source of fear," according to an inscription on one of his preparatory installation drawings.[47] The snakelike form of Miró's frieze formed the centerpiece of this unconventional spatial configuration, in which the different displays were unified through a giant green canvas (rather than a white one, as Duchamp had proposed) that stretched around the circular room.

Fig. 2.12

Denise Bellon (French 1902-1999)

Friedrick Kiesler΄s Anti-Taboo Figure and Marcel Duchamp΄s Le Rayon vert (The Green Ray) in the background, Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, 1947

Fig. 2.13

Denise Bellon

Duchamp΄s Green Ray, 1947 (now lost)

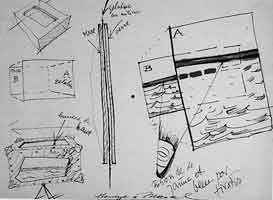

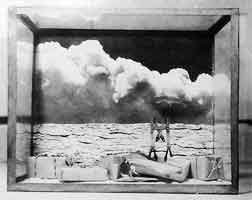

---- For many years, Kiesler's discombobulating design may explain why Duchamp's contribution, The Green Ray (figs. 2.12 and 2.13), was confused with another photo-collage on display, in which wrapped paper packages and a pair of lederhosen suspenders were framed against a seascape and cloudy sky (fig. 2.15).[48] Although Duchamp supplied Kiesler with written instructions on how to execute The Green Ray, the architect's preparatory sketches suggest that the final design probably departed from his friend's initial concept. The work consisted of a small photographic object installed behind an elliptical hole approximately five inches in diameter and cut at eye level into the thick green canvas that partitioned the space.[49] Through the peephole, visitors could discern a view of a calm sea separated from a cloudless sky by a flashing band of green light that illustrated the so-called green-flash, or green-ray, effect. This rare natural phenomenon is visible at certain latitudes on a clear day when the sun rises or drops behind the horizon at sea. As the last ray of the setting sun, or the first ray of the rising sun, skims the surface of the water, it produces for a fraction of a second a refulgent emerald-green light of great intensity. Kiesler's ink-and-gouache study for the installation of The Green Ray indicates that photographs of sea and sky were inserted in a small wooden shadowbox illuminated by a lightbulb that blinked at regular intervals (fig. 2.14). These images were separated along the line of the horizon by a narrow slit, into which Kiesler fitted two glass panels, one yellow and one blue, with gelatin in between; when viewed through the peephole, the glass and gelatin coalesced in the eye of the beholder into a shimmering green light.[50] The seascape diorama was placed at a slight angle, so that the slanted horizon line gave the viewer the impression of being on a boat in a roiling sea. This nautical reference was underscored in the exhibition checklist, which described the work as "Un hublot laisse passer le Rayon Vert de MARCEL DUCHAMP" (Through a porthole shines the Green Ray by Marcel Duchamp).[51]

Fig. 2.14

Frederick Kiesler

Study for The Green Ray, 1947

Ink and opaque watercolor on paper, 25,2 × 35,4 cm (915⁄16 × 1315⁄16 inches)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the Katharine Levin Farrell Fund, 1992-64-1

Fig. 2.15

Unidentified work on view at the 1947 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, long misidentified as Duchamp΄s installation The Green Ray

---- Art historian Herbert Molderings has convincingly connected the work with one of Jules Verne's Voyages extraordinaires, published in 1882 under the title Le Rayon-vert.[52] This romantic novel tells the story of Helena Campbell, a young Scotswoman who reads about the rare natural occurrence of the green ray in the local Morning Post, and associates the phenomenon with an ancient Highlands legend that described a ray of green light that renders those who see it incapable of deception in matters of love. Determined to see the capricious ray, which the newspaper had promised would be "a most wonderful green, a green which no artist could ever obtain on his palette,"[53] Miss Campbell sets off on a series of adventures in the company of her uncles and two young men who are madly in love with her, a self-important amateur scientist and geologist with the ludicrous name of Aristobulus Ursiclos and a painter, Oliver Sinclair. While the pedantic savant offers a scientific explanation of the phenomenon as an optical illusion — the result of afterimage effects and the mixing of complementary colors in the eye — the artist supports the young woman's romantic understanding. Ursiclos thus fails to win Miss Campbell's heart because he has stripped the ray of its poetry, materialized her dream, and transformed "the scarf of some Valkyria with its fringe trailing in the water on the horizon" into nothing more than "a brutal optical phenomenon." As Verne sadly observes, "Perhaps she might have forgiven him anything but this."[54]

Fig. 2.16

Willy Maywald (German, 1907-1985)

Photograph of the Hall of Superstitions, 1947 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

Left to right: Matta, Whist; Kiesler and Hare, Anxiety Man; Miró, Cascade of Superstitions; Tanguy, The Ladder Announcing Death; On the floor: Ernst, Black Lake

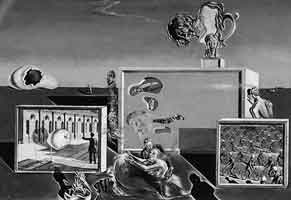

---- It is easy to see how Duchamp, with his playful, ironic, nonlinear mind, would have identified with the painter, who wins the girl by wittily discrediting the rational arguments of his rival. Sinclair parodies Ursiclos's scientific explanations to comic effect by suggesting that he investigate such absurd notions as "the influence of fishes' tails on the undulation of the sea," and the effect of "wind instruments on the formation of tempests."[55] Duchamp may have been aware of Verne's novel before 1947, since it was admired by the Surrealists. Much of the novel's imagery resonates with Duchamp's own experiments related to optics and stereoscopy, as well as his notes for The Large Glass, which describe the Bride's discarded garments as lying on the horizon,[56] much like the hem of the Valkyria's sash. Duchamp's interest in the optical phenomenon of the green ray recalls, too, his work on Étant donnés, where the atmospheric effect of the sparkling waterfall appears at irregular intervals through a hidden light source, in a manner analogous to the blinking lightbulb of the 1947 installation. The use of a porthole for his own Green Ray suggests that in the late 19405 Duchamp was still thinking of a single opening rather than a binocular viewing device for Étant donnés, perhaps in terms similar to those of Salvador Dalí's Illumined Pleasures (1929), in which a young man masturbates while looking through a peephole into a deeply recessed chamber whose forbidden sexual content, like his own presumably erect penis, is hidden from view (fig. 2.17).

Fig. 2.17

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Illumined Pleasures, 1929

Oil and collage on composition board, 23,8 × 34,9 cm (93⁄8 × 133⁄4 inches)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection, 1967

Fig. 2.18

Willy Maywald

Gallery view of the Rain Room, conceived and designed by Frederick Kiesler,

with Maria Martins΄s sculpture Impossible on a billiard table

1947 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

Vintage gelatin silver print on barite paper

Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna

---- Kiesler had hoped that visitors would abandon rational thinking in the Hall of Superstitions before they proceeded into the Rain Room devised by Duchamp, which, like the 1938 Surrealist exhibition, brought elements of the natural world into an indoor architectural space (fig. 2.18). This room juxtaposed curtains of torrential rain pouring down on artificial grass with a billiard table that served as a pedestal for Maria Martins's sculpture Impossible. The installation thus placed the secret relationship between Duchamp and the Brazilian artist on public display, even though many exhibition visitors would have been unaware of the sculpture's private significance. Having passed through the Rain Room, visitors reached the Labyrinth of Initiation, a long rectangular space that was painted midnight blue and divided into twelve octagonal spaces. Each of the twelve recesses contained a votive altar that corresponded to a sign of the zodiac or a mythological being. These recessed altars were reached through narrow passageways connected by strips of reflective metal and twisted wire that formed a transparent Ariadne's thread, in reference to the Greek myth in which Ariadne's lover, Theseus, used a line of string to retrace his steps and escape from the Minotaur's labyrinth.[57] This navigational device also recalls Duchamp's famous "Sixteen Miles of String" installation at the 1942 Surrealist exhibition in New York.

---- The seventh altar in the Labyrinth of Initiation, under the sign of Libra, was dedicated to Duchamp's mysterious Juggler of Gravity (fig. 2.19), an element that was planned but never realized in the artist's Large Glass. Duchamp had conceived this altar prior to the exhibition's installation, but it fell to Roberto Matta to execute the shrine. This work consisted of a precariously tilted pedestal table holding on its circular, platelike surface a white ball, which should have fallen to the ground but instead defied gravity, as the title suggests. The ball of The Juggler of Gravity echoed the billiard table in Duchamp's Rain Room, which served as the base for Martins's sculpture Impossible, thus suggesting that the two installations were linked by the artist's interest in precariously balanced objects and relationships. Many of the other altars featured totemic sculptures and bizarre, imaginary creatures, such as the Romanian painter Victor Brauner's Wolf Table and the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam's Hair of Falmer, once again forcing visitors to confront their deep-seated fears before exiting the exhibition.[58] The original plan was for newly initiated visitors to pass through a kitchen, in which after their trials they would find reward in the form of Surrealist dishes, but in the end this project was replaced with a bookshop.[59]

Fig. 2.19

Willy Maywald

Marcel Duchamp΄s installation The Juggler of Gravity, 1947

Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme

Collection of Herbert Molderings, Paris

---- Like Duchamp, Kiesler viewed exhibition design as a new artistic medium, and their collaboration on the 1947 Surrealist exhibition once again placed special emphasis on the interaction between the viewer and the works of art. As we have seen with Duchamp's designs for earlier Surrealist exhibitions, as well as Kiesler's Art of This Century gallery, visitors became active participants in a multisensory, all-enveloping environment that encouraged a dynamic relationship with their surroundings. Their goals add a new level of meaning to the Prière de toucher cover design for Le Surréalisme en 1947, which instructed visitors to ignore the standard "do not touch" protocol of the traditional art museum or gallery, and physically engage with the works of art on display. Furthermore, the initial designs for the cover closely resemble the shape of Martins's left breast in the Étant donnés mannequin, and again help us to date the artist's plaster casts of her body to about 1946.

---- Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

* Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 61-75, pp. 120-121. (Published on the occasion of an exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aug. 15 - Nov. 1, 2009.)

© 2009 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Notes:

[1] On January 24, 1969, Anne d'Harnoncourt, then a young curatorial assistant beginning work on the installation of Étant donnés at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, interviewed Teeny Duchamp regarding the construction of the piece. This would be the first of many interviews between the two women that took place during the early months of 1969. After the work went on public display on July 7, 1969, d'Harnoncourt typed up her handwritten notes from these interviews in a twelve-page report, coauthored with Museum Conservator Theodor Siegl, entitled "Notes on the History of the Tableau" and dated September 1969, which is now housed in the Anne d'Harnoncourt Records (hereafter AdH Records) at the Archives of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This unpublished document provides the most complete account of the construction of Étant donnés, although it should be pointed out that Teeny Duchamp had no knowledge of the tableau-diorama prior to 1951, when she met the artist. However, her discussions with Duchamp about the work carried out before that date offer a unique perspective on the making of the mannequin and its related studies in the 1940s. In addition to the "Notes on the History of the Tableau" manuscript, my account of the construction of Étant donnés also relies on interviews that I conducted over the past fifteen years with Teeny Duchamp, Anne d'Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Paul Matisse, and Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, and I am extremely grateful to these individuals for providing invaluable insights into Duchamp's working process and materials.

[2] See "Columbia Art Staff Increased," New York Times, June 4, 1937, p. 21. A former Guggenheim Fellow in sculpture, Ettore Salvatore (1902-1990) had studied in New York at the Architectural League, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, and Cooper Union before being appointed instructor in casting at Columbia University; see "Art Classes at Columbia Open Thursday," Washington Post, September 25,1938, p. 9.

[3] See Amy Lyford, Surrealist Masculinities: Gender Anxiety and the Aesthetics of Post-World War I Reconstruction in France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), p. 67.

[4] Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85 was published in View, ser. 5, no. 1 (Marcel Duchamp Number) (March 1945), p. 54. Salvatore retained possession of this plaster life cast, and in the early 1960s he made large bronze and plaster editions of the work, which he sold to museums and private collectors, including Joseph H. Hirshhorn, for whom he hand-colored Duchamp's portrait with a reddish pink pigment to give it the impression of skin tones. Now in the permanent collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, this version is inscribed "Ettore Salvatore, 1963." Salvatore also made a life mask of Hirshhorn in 1966, at the same time he sold him the Duchamp plaster and a bronze head of Abraham Lincoln; the invoices for all three sculptures reveal that the artist made these works at the Roman Bronze Works in Corona, New York, and at the Plaster Casting Studio at 90 Morningside Drive in New York, where he lived. These plaster versions relate to Salvatore's work as a board member of Sculpture Collectors Limited, a New York-based company that produced authorized full-size editions in bronze and foundry stone of famous sculptures by Honore Daumier, Paul Gauguin, and Auguste Rodin.

[5] See Cennino d'Andrea Cennini, Il Libro dell'arte / The Craftsman's Handbook, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), pp. 124-29.

[6] The circumstances surrounding the making of Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85 were recounted by Frederick Kiesler in an unpublished manuscript in the Kiesler Archives at the Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation in Vienna. According to Kiesler's account, Duchamp hired the African-American photographer Percy Rainford (whom Kiesler referred to as "ein junger neger") to take the photographs on the evening of January 13,1945. I am extremely grateful to Dieter Bogner, the foundation's president, for sharing with me this important ten-page typescript.

[7] See John Bernard Myers, "Interactions: A View of 'View,'" Art in America, vol. 69, no. 6 (Summer 1991), p. 85.

[8] Frederick Kiesler, "Kiesler on Duchamp," Architectural Record, vol. 81, no. 5 (May 1937), p. 53.

[9] To assist Kiesler in his ambitious two-page spread for View, Duchamp provided him with the transcript of a recent interview he had given to James Johnson Sweeney, in which he discussed, among other matters, the literary sources for The Large Glass. This interview, now housed in the archives of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers, Interviews, box 3, folder 16), was mistakenly attributed to Kiesler by Maria Bottero, who dated the interview to shortly before Kiesler's 1937 Architectural Record essay on The Large Glass (see note 8 above); see Bottero, Frederick Kiesler: Arte, architettura, ambiente, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1996), p. 212. However, the transcript corresponds exactly with an interview that Duchamp gave to Sweeney in 1945, which was later published in Sweeney, "Eleven Europeans in America," Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, vol. 13, nos. 4-5 (1946), pp. 19-21, 37.

[10] Frederick Kiesler, diary entry, March 10, 1959, in Maria Bottero, "Kiesler Observed by Lilian Kiesler: in Bottero, ed., Frederick Kiesler: Arte, Architettura. Ambiente, exh. cat., Galleria della Triennale (Milan: Electa, 1995), p. 181. Luna Park operated from 1933 until 1944 as an amusement park at Coney Island in New York.

[11] See Celia Rabinovitch, Surrealism and the Sacred: Power; Eros, and the Occult in Modern Art (Boulder, CO: West-view, 2002), p. 61.

[12] As Linda Dalrymple Henderson has argued, the 1945 View triptych suggests that Duchamp's studio was filled with three-dimensional counterparts to the components of The Large Glass. For example, on the top left edge of the bookcase stands the empty bottle of Bordeaux that Duchamp used for the cover design of this special issue of View. Henderson compares this bottle to the falling Benedictine Bottle/Weights of the chariot-mechanism of The Large Glass, and connects it to the Malic Mold in uniform since the bottle bears a label made from the artist's service record. The precariously placed bottle is joined on the bookcase by nine implements, including screwdrivers, that Henderson views as surrogates for the nine Malic Molds. She also suggests that the box of Jack Frost sugar cubes on the top shelf may be a reference to the artist's assisted readymade Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? (1921), a metal birdcage filled with 152 white-marble "sugar" cubes; see Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in The Large Glass and Related Works (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), p. 215.

[13] Frederick Kiesler, "Kiesler on Duchamp," Architectural Record, vol. 81, no. 5 (May 1937), pp. 53 60.

[14] Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "Frederick Kiesler and The Bride Stripped Bare ...," in Yehuda Safran, ed., Frederick Kiesler, 1890-1965, exh. cat. (London: Architectural Association, 1989), p. 66.

[15] Sec Penny Howell Jolly, "Antonello da Messina's Saint Jerome in His Study. An Iconographic Analysis," Art Bulletin, vol. 65, no. 2 (June 1983), p. 239. As Jolly argues, the painting can be divided into nine parts, since "the triple arrangement of the windows on the uppermost level is repeated by the triple arrangement of landscape/Jerome/landscape in the middle portion of the painting, and by the triple arrangement of partridge/peacock/basin on the lowest level"; ibid.

[16] See David Hopkins, Dada's Boys: Masculinity after Duchamp (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 102.

[17] Charles Henri Ford, letter to Parker Tyler, undated (April 20, 1939?), Harry Ransom Humanities Center, University of Texas at Austin, Charles Henri Ford Papers, quoted in Dickran Tashjian, A Boatload of Madman: Surrealism and the American Avant-garde, 1920-1950 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995), pp. 170-71.

[18] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, May 24 [1949].

[19] Mark Polizzotti has noted that, despite Breton's enthusiasm for Duchamp's witty cover design, Charles Duits — one of the writer's young protégés in the Surrealist group — felt that "they were making fun of my great man"; see Polizzotti, Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), pp. 518-19.

[20] Breton, "Lighthouse of the Bride," View, ser. 5, no. 1 (March 1945), p. 13.

[21] Enrico Donati, interview with the author, New York, December 14, 2006.

[22] Maria Martins, quoted in "Underground Art," Time, vol. 62, no. 18 (May 6, 1946), p. 64.

[23] Maria Martins, letter to Evan H. Turner, April 15, 1969, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Archives, Evan Hopkins Turner Records, Museum correspondence, box 33, folder 37. Writing in French from Vienna, where she was residing at the time, Martins related to Turner that this drawing was the first study for Étant donnés: "Je posséde aussi le premier dessin de ce travail."

[24] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, September 6 [1948].

[25] For more on the friendship and correspondence between Mary Reynolds, Duchamp, and the Hoppenots, see "Mary Reynolds et Hélène Hoppenot, confidences: Un Dialogue à travers les lettres de Mary Reynolds et le journal intime d'Hélène Hoppenor," Étant donnés Marcel Duchamp, no. 8 (2007), pp. 106-45.

[26] See Stefan Banz, "Le Forestay: The Waterfall in Marcel Duchamp's 'Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage,'" trans. Catherine Schelbert, in Eclairages: Regards sur les collections du Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts/Lausanne, no. 1 (2007), unpaginated.

[27] Hugh Shaw, letter to Anne d'Harnoncourt, August 22, 1969, AdH Records. D'Harnoncourt remained convinced that this work dated to 1946 rather than 1948-49; interview with the author, Philadelphia, June 28, 2007.

[28] For the full inscription and its English translation, see Melissa S. Meighan, "A Technical Discussion of the Figure in Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés," p. 259n10, in Taylor, Michael R.; Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés, Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009.

[28-a] Melissa S. Meighan, "A Technical Discussion of the Figure in Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés" in Michael R. Taylor; "Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés," Philadelphia Museum of Art & Yale University Press, 2009, pp. 241-44.

[29] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, July 11 [1947].

[30] Marcel Duchamp, letter to Maria Martins, September 6 [1948].

[31] Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, A Marriage in Check: The Heart of the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor, Even, trans. Paul Edwards (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2007), p. 74.

[32] Denise Browne Hare, interview with the author, New York, July 12, 1996.

[33] Working independently and without access to the unpublished materials at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rhonda Roland Shearer also concluded that the Étant donnés mannequin was assembled from various casting of Maria Martins's body. In a video demonstration made with Robert Slawinski, Shearer presented the figure as an assemblage of individual body parts, which she argued imbued the mannequin with the fourth-dimensional aspect see Shearer and Stephen Jay Gould, "Drawing the Maxim from the Minim: The Unrecognized Source of Niceron's Influence upon Duchamp," Tout-fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studied Online Journal, www.toutfait.com (accessed March 17, 2009)

[34] The movement's increasing preoccupation with the esoteric and the occult rather than left-wing politics came under fire at this from the poet and artist Christian Dotremont, who recently had founded the dissident Surréalisme Révolutionnaire group in Belgium; see Mary Ann Caws, Surrealism (London: Phaidon, 2004), p. 41.

[35] Enrico Donati, interview with the author, New York, December 14, 2006. In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp inexplicably downplayed Donati's key role in this joint venture, even claiming that he himself was the one who "had seen these sponge-rubber 'falsies' they sell in stores. I had to finish them, because, since they were made to be hidden, the manufacturers hadn't bothered with the details. So I worked on making little breasts. with pink tips"; Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking, 1971), p. 87.

[36] Rosalind E. Krauss, "The Im/pulse to See," in Hal Foster, ed., Vision and Visuality (Seattle: Bay Press, 1988), p.60.

[37] Enrico Donati, interview with the author, New York, December 14, 2006.

[38] Ibid.

[39] In a long letter to the artists, including Enrico Donati, who were to participate in the exhibition, written on January 12, 1947, the eve of Duchamp's departure for New York, Breton meticulously described the installation plans; The Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, Los Angeles, Enrico Donati Papers, André Breton Letters, folder 2. The installation design of the 1947 Surrealist exhibition also has been discussed at length by Marcel Jean, The History of Surrealist Painting (New York: Grove, 1960), pp. 341-44; José Pierre, "Le Surréalisme en 1947," in La Planèle affolé; Surréalisme; dispersions et influences, 1938-1947, exh. cat. (Marseilles: Centre de la Vielle Charité, 1986), pp. 282-319; and Alyce Mahon, Surrealism and the Politics of Eros (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005), pp. 107-40.

[40] André Breton, "Devant le rideau," in Le Surréalisme en 1947, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Maeght, 1947), p. 18 (my translation).

[41] Jean, The History of Surrealist Painting, p. 342.

[42] Duchamp later admitted to Pierre Cabanne that, "as an architect, [Kiesler] was far more qualified than I to organize a Surrealist exhibition"; quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p. 86.

[43] Jean, History of Surrealist Painting, p. 342.

[44] Ibid., p. 341.

[45] Frederick Kiesler, quoted in Jean Arp, "L'Oeuf de Kiesler et la Salle des superstitions," Cahiers d'art (Paris), vol. 22 (1947), p. 281 (my translation).

[46] Frederick Kiesler, "L'Architecture magique de la Salle de superstition," in Breton, Le Surréalisme en 1947, p. 134n* (my translation).

[47] This drawing is reproduced in Cynthia Goodman, "The Art of Revolutionary Display Techniques," in Lisa Phillips, ed., Frederick Kiesler, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art and Norton, 1989), p. 72.

[48] This error was resoundingly corrected by Herbert Molderings; see Molderings, "Objects of Modern Skepticism," in Thierry de Duve, ed., The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1991), pp. 257-61, 267-75.

[49] Kiesler also placed Ernst's painting Euclide behind the green curtain, where it was visible through a similar peepshow-like aperture.

[50] See Molderings, "Objects of Modern Skepticism," p. 259.

[51] The exhibition checklist is an unpaginated, four-page leaflet, not to be confused with the catalogue Le Surréalisme en 1947, in which The Green Ray is mentioned only in a footnote on p. 134; see Molderings, "Objects of Modern Skepticism," p. 264n39.

[52] Molderings, "Objects of Modern Skepticism," p. 259.

[53] Jules Verne, The Green Ray (Holicong, PA: Wildside, 2003), p. 16.

[54] Ibid., pp. 86, 88.

[55] Ibid., p. 87.

[56] Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds., Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du sel) (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 20.

[57] See Arp, "L'Oeuf de Kiesler et la Salle des superstition," p. 286.

[58] The title of Lam's altar refers to an episode in Chant IV of Isidore Ducasse (the "Comte de Lautréamont"), Les Chants de Maldoror (1868-69), a long narrative prose poem that was greatly admired by the Surrealists.