I Was Waiting for Marcel (Frederick Kiesler)

Herbert Molderings

Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85

An Incunabulum of Conceptual Photography

(Part 4)*

* Herbert Molderings; Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85: An Incunabulum of Conceptual Photography, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Köln, 2013,

pp. 96-111. (Translated by John Brogden, Foreword by Dieter Bogner)

© 2013 Herbert Molderings and Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Köln

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 ----

FREDERICK KIESLER

---- “I was waiting for Marcel — it was 5.35 p.m. at 42 West 57 Str.,

-------- January 13, 1945.”

Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage, Maria Martins, Enrico Donati (back row), Marcel Duchamp and Frederick Kiesler (front row) in front of Kay Sage’s house in Woodbury, Connecticut, circa 1946-47.

---- Editor’s note

The typescript kept under inventory no. TXT 6170/0 at the archive of the Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna, consists of ten loose, one-sided typewritten, paginated folios measuring 27.8 x 21.4 cm. It is neither dated nor signed. By reason of certain particulars given in the text, the correctness of which is verifiable by other documents, the script can be ascribed to Frederick (Friedrich) Kiesler beyond all shadow of doubt. It is the draft of an article intended for publication in the “Marcel Duchamp Number” of the avant-garde magazine View: The Modern Magazine and was probably written between January I3 and March 1945, but was not published. For an in-depth commentary on the authorship and content of this draft please refer to the essay in this publication entitled “Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 8s: An Incunabulum of Conceptual Photography.”

The frequency of deletions and substitutions in the typescript suggests that the article was written directly into the typewriter. In the second stage, which consisted in the editing of the text with pencil, certain typographical and punctuation errors were corrected, words and parts of sentences deleted and replaced by others, and some sentences were transferred to other parts in the text. The article is composed in a spoken rather than written style, which not only explains a certain negligence of expression but also gives reason to assume that the text was dictated to a second person who typed it. The German of the original typescript is peculiar. It is not literary German but rather the colloquial German of an Austrian who grew up in the Jewish community of Czernowitz in the easternmost part of the then Austro-Hungarian Empire, studied and worked in Vienna and then, from the mid-1920s, lived in the USA. The linguistic mix that came about through Kiesler’s many changes of abode is strongly reflected in the original German typescript. The opening sentence, written in English, and the occasional use of English words in the German text (“appropriately”, “screen”) are a direct echo of the fact that Kiesler had been living in New York since 1926. As the article was intended for publication in the American magazine View: The Modern Magazine, it would still have to have been translated, but no English version of the article has so far been located or proved to have existed.

H.M.

----

Translator’s note

While the translation is an accurate rendering of the content, no attempt has been made — nor would it have been desirable or even feasible — to render the text in an equally peculiar English. Words and passages deleted by the author in the original typescript are indicated in the endnotes. There are two kinds of deletions: words that have been x'ed out while the text was still in the typewriter and words that have been deleted in pencil after removal from the typewriter. The deletions specified in the endnotes have been distinguished accordingly.

The paragraph divisions of the original typescript have been retained. Any additions made by the editor or the translator for the sake of clarity have been set between square brackets.

[fol. 1] I was waiting for Marcel — it was 5.35 p.m. at 42 West 57 Str., January 13, 1945.[1]

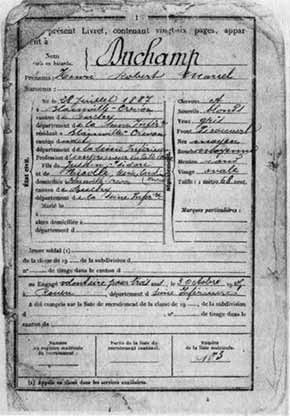

The photographer came out from behind the curtain,[2] holding[3] some wet photographs in his hand. A young Negro was lighting gas burners inside a drum, around which ran a double belt of canvas.[4] The photographer put the wet photographs, which were clogged together, on the table in front of me. He then went over to the young Negro and showed him the lever that set the drum in motion. The canvas belt began to run around the drum and from there under a metal tank, which looked like an open rain gutter, passing through a slot in the table, then around a mobile framework that articulated to and fro, continuing[5] before disappearing and then coming into view again on the other side of the drum.[6] The photographer took 3, 4 steps,[7] grabbed hold of a clean, white cloth, crumpled it up, detached the top photograph from the wet clump, laid it flat down on the table and[8] wiped it rapidly and energetically front and back with the cloth in order to soak up as much water as possible. This was the first of 11[9] photographs that the 2 of us[10] had taken of Duchamp and his studio 2 days previously on the 4th floor of the house at 210 W 14 Str.[11], [12] The photographer took hold of one of the corners of the 1st print and peeled it off the table, took it across to the machine and laid it on the bed of the rotary canvas dryer [fol. 2] and then went back for the next one, repeating the to-ing and fro-ing until all the prints [were] thus bedded and had disappeared into the toasting machine. At that very moment, I heard the door open and Marcel was in the room. His hair was grey. He looked ill. “Marcel, are you[13] all right?” “I have to[14] look even worse,”[15] he answered. He had[16] [taken] out of his pocket[17] 1 powder compact, 1 eyeliner pencil, 1 clean and neatly folded handkerchief, 1 pair of gold-rimmed spectacles, and a beret. Now I understood. He had come to have his portrait taken at the age of 84. The photographer was standing in front of the machine and, like a midwife,[18] waiting for the dried prints[19] to emerge. Marcel took off his coat, asked for a room with a mirror and disappeared down the hallway. The photographer[20] was now cutting the prints to size. [I] stood up and, after taking about five steps, was standing next to him and looking, for the very first time, at the photographs he and I had taken. One of the prints was still lying on the table, slightly rolled up, only half dry. I recognized the bottle[21] that I [had seen] at Marcel’s a fortnight ago, the one he had prepared for the photography sitting. Marcel appeared. His hair was whiter, his eyebrows as white as snow, his unshaven chin grey. He pointed to his tie, a[22] black, self-tied one, 1900 style. He gave a broad, thin-lipped laugh and struck a pose, his mouth imitating that of a toothless old man. He asked for the photograph of the bottle.[23] It was shown to him. Two other prints were brought in. He wished to know which one was deeper black, asking me, and then the photographer and then the boy. Another man emerged from the darkroom. Marcel gave him the 1st print: [fol. 3] “Can you change this black into a sepia?” “Easy,” he replied, disappearing behind the black curtain. “You'll have to help me finish my make-up.” I accompanied Marcel into the other room, which looked like a cave, unfurnished except for a roller blind that hung down askew, an iron bedstead with a blue blanket and a large mirror on the wall, illuminated by a naked electric light, in front of which Marcel was already standing. We studied his face in the mirror for a few seconds and then another few seconds later we were back in the room. Marcel sat broadly in the chair; his head leant back, as though he were at the barber’s. [ grabbed the white handkerchief, wiped those parts of his hair and face that were too white and dusted the white powder off his black tie. Both of us agreed that the patches of grey on the black tie were very apt and suitable. “I have just bought the tie,[24] it’s new.” A few black lines across his brow, a deepening of the nasolabial folds, which Marcel had already deepened slightly, a powdering of the ears, which we had forgotten, thin black lines on both edges of the nose[25] and at the end of the nasal cartilage. Meanwhile the photographer had set up the lamps and switched them on.[26] He was now putting up a roll of white paper in the background; Marcel interrupted him — and me in my make-up work — and asked for a black background. The photographer and I looked at Marcel in his shirt, his pale face, his black beret [fol. 4] and black tie and considered him ready. Marcel wished to put on his dark jacket, as he feared he might be too easily recognizable in his shirt. The boy brought the jacket. Marcel[27] stood up, put on the jacket, took [a] few steps towards the light and sat down on a chair in front of the black background.[28] He was grinning like a very old man. I went over to him with the handkerchief, the black pencil and the powder compact and checked everything one more time. The photographer was already behind the camera under the focusing cloth. Marcel insisted that the light must come from high up so as to make the shadows[29] in the face sharp. The ceiling lamp, which created this effect quite naturally, could not be used, as it was too weak. In order to obtain the same effect, somebody would have to hold up the artificial lighting while the photograph was being taken. The assistant was called, the boy also came in, and the 2 of them raised the lamps. I stepped back, but still managed in a fleeting moment to pull down the collar of Marcel’s jacket at the back in order to accentuate even more the sunken sitting posture. Marcel asked for the spectacles. I took them from the table, placed them on his ears and nose, letting them slide slightly down the ridge of his nose. “Not too low,” Marcel insisted. I noticed that the lenses of the spectacles were[30] smeared and powdered (Marcel had evidently already prepared them in his studio). Marcel struck his grinning pose once more,[31] but begged me to keep a close watch on the[32] sunken lines around the mouth, as he would now widen and narrow them. I was to decide what was[33] not too wide and not too [fol. 5] narrow for an old man of 84. The photographer, still under his focusing cloth, called to me, voicing his enthusiasm about what he could see. I came and looked through [the camera].[34] The 2 assistants[35] were still holding up the lamps. I stepped back. Marcel remained motionless, frozen [in his pose]. The photographer released the shutter, changed the dark-slide and released the shutter again. Without moving his head, Marcel asked me to remove his spectacles. I did so. “The question is whether 84 would come out better with or without glasses.” The camera clicked another two times. “Can you develop that straight away?” “Certainly.” The photographer pulled out the dark-slide and was already passing through the curtain when Marcel, still seated, called to him: “Put your hand in my coat pocket.[36] It’s hanging over there. There’s a small roll of film in it.” The photographer brought forth the roll of film. Marcel stood up, took the roll of film into his hand and said to the photographer, “It is only so long,”[37] and spread his arms apart, “about 7 foot.[38] I'd like you to make prints from it, simple contact prints. You may cut the film into short pieces if you like, so they will fit into your bath, [ don’t mind.” “Oh, no,” the photographer replied, “I can do it without cutting it,” and disappeared behind the black curtain. The camera now stood unattended, the lamps had been placed on the floor, everybody was waiting for the test prints. The assistant appeared with a dripping print of the bottle.[39] Marcel and I stood in the light of the ceiling lamp and scrutinized the wet print, which stayed stuck[40] to the palm of the assistant’s hand. [fol. 6] The tonal transformation had been successful. The print was now a golden brown. “Excellent,” Duchamp said loudly and[41] turned towards the table on which the 2 other black prints of the bottle were lying. The assistant ignited the drying drum and began[42] the process of drying the prints. Marcel[43] spread the two prints out flat and held them close to my face, one in each hand. “Which print,” he said, “is the darker one? This is very important. It’s for the enlargement for printing.” They were astonishingly equal in shade. I chose one, Marcel chose the other. The[44] photographer[45] appeared from behind the curtain and lit a cigarette. Marcel held the two prints towards him. “Which one is darker?” he asked without taking his eyes off the prints. The photographer chose the 2nd one. I had lost. The assistant, who was now standing next to us at the machine, stretched out his[46] hands towards the drum. The print dropped into his hand. He brought it over to us and then withdrew. Marcel[47] dashed through the hallway into the [other] room, saying: “I've got to be downtown at[48] 7 o’clock.” The photographer disappeared behind the curtain.[49] I sat down at the table, gathered my 11 prints together and began to pack them into my briefcase.[50] He came back. “But first I must go home, 14th Street, to brush the powder out of my hair and to shave off the beard I've been growing for the last 3 days.” He began to stuff his beret, powder compact, and the other props into his pocket. “There are 72 images on this 7-foot [fol. 7] roll of film,” he said, smiling cheerfully through his hoary, mask-like makeup. “Printing one image from the film on each page will give a moving image when you flip through the pages. You must leave me a small space on two of your pages, about 1 to 2 cm square.”[51] There was a movement behind the curtain and out came the photographer, laughing, the palms of his 2 hands holding towards us 2 dripping prints of the photographs he had taken a few minutes before.[52] Marcel with and without glasses. We bent down over them. “Which one shall we use? The one with glasses looks like 84, the one without only like 79.” “May I take them with me?” Marcel asked the photographer, who then stepped to one side and ignited the drying machine. Marcel had already put on his overcoat, and I mine. He took the brown print, which was still lying on the table, into his hand and was about to put it in the envelope he was holding.[53] I looked at the bottle.[54] “Marcel,” I said, “I remember how you prepared the bottle; it was about 3 weeks ago, when [ visited you in your studio in order to check some of the known dates from your life.[55] On your work table was a large sheet of paper with a small pile of dust in the middle,[56] lit by an overhanging desk lamp. On the same sheet of paper was a thick piece of cardboard, about 1 foot by [fol. 8] 2, which had been scraped hollow all over. For hours and days on end you had probably been scraping away at the cardboard with a knife or some similar implement in order to produce[57] a whole mass of dust, which you then gathered up into a pile.[58] You then brought a bottle from out of the table’s shadow and told me that it had been rather difficult to find a genuine Bordeaux bottle, but now you had managed to do so and were happy about it. You explained that the cardboard dust[59] had been made for the purpose of mixing it with a slightly sticky solution to make a pulp, with which the glass of the bottle would then be coated. When it had dried slightly, the pulp would then have to be scraped off the bottle, but only lightly, only so much that the dark glass would just shine through the thin layer of dust and the scratches. You then asked me whether I considered one spot that had already been prepared in this way, after the application of several layers of dust, better than another spot, which was still a pulpy clump, with cracks and fissures, like dried-out mud. I found this spot more expressive than the other for your presumed purpose, namely to make the bottle look antiquated and to fake decades of cellaring. You liked the other side of the bottle. You then turned the bottle round to show a long, stuck-on label and asked me, smiling somewhat, where the label came from. It was written in fine handwriting and in small print and looked like a document, indecipherable except for your name, which [fol. 9] stood at the top in large letters. To my great astonishment I saw that you have two other first names, Henri and Robert, and remarked happily that I was very glad that your name has an H in it. You asked me why, and [ said that I myself had given you the name of Hyronymus [sic] and could therefore retain the H without any fakery.[60] It was, you now explained, a photograph[61] which you had appropriately[62] treated with diluted lacquer and light shades of color and stuck on [the bottle] as a label. It is a reproduction of your certificate of discharge from the French army of the First World War.[63] You then explained the smoke effect you wished to obtain from the neck of the bottle, the natural sunshine that would be necessary in order to create the cloud effect.[64] But what now interests me in particular is that you were intent on photographing the whole bottle again and then making a tiny 2 centimeters square block so as to obtain an image with a coarse [halftone] screen.[65] You said you would then have a print made from the tiny block, enlarge it to this magazine’s format of 7 by 10,[66] making the reproduction of the bottle dissolve into large, heavy dots through the enlarged screen. You would then overprint it with the same bottle in a fine screen in 2 other colors and in this way obtain an interesting texture. [fol. 10] Now I see from this brown print that[67] the entire text of the label has been lost, not only because of the coarse screen but also because you did not photograph the bottle upright but laid almost flat and foreshortened, making it impossible to read the label. As they are unfortunately illegible on the bottle, may I now ask your permission to reproduce in this article the personal particulars of your military document, which are on the bottle and at all events give reason to assume appropriate credibility.” “But of course,” Marcel replied. And here is the document:

Personal particulars from Duchamp's military ID pass of 1905.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 ----

* Herbert Molderings; Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85: An Incunabulum of Conceptual Photography, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Köln, 2013,

pp. 96-111. (Translated by John Brogden, Foreword by Dieter Bogner)

© 2013 Herbert Molderings and Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig, Köln

Notes:

[1] The title of the original German text is written in English. With the aid of the entries in Stefi Kiesler’s diary dated January 1 and 11, 1945 (Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation), the photographer can be readily identified as Percy Rainford. The number of the house — 42 — is either a typing or a memory error on Kiesler’s part. The studio was located not at 42 but at 44 West 57th Street. See note 72 of the essay “Marcel Duchamp at the Age of 85” (Part 1).

[2] said, x’ed out on typewriter.

[3] 11, x’ed out on typewriter.

[4] and [...] himself, x’ed out on typewriter.

[5] and, x'ed out on typewriter.

[6] Pencilled arrow denoting continuation of paragraph.

[7] to his table, x’ed out on typewriter.

[8] carefully pressed, x'ed out on typewriter.

[9] prints, X ed out on typewriter.

[10] he and I, x'ed out on typewriter.

[11] According to the entry in Steh Kiesler's calendar diary, the photographer Percy Rainford had, under Frederick Kiesler’s instructions, taken photographs of Marcel Duchamp’s single-room apartment at 210 West 14th Street on January 11, 1945. Having previously lived with the Kieslers as a lodger for a year, Duchamp had moved into this studio apartment in the autumn of 1943. He kept this room until 1965, but used it just as a studio from 1954 onwards.

[12] The first print wiped dry, x'ed out on typewriter.

[13] ill? I asked him, deleted in pencil.

[14] am going to, deleted in pencil.

[15] “I must look like 84”, deleted in pencil.

[16] already, deleted in pencil.

[17] one, deleted in pencil.

[18] Here Kiesler uses the word accoucheur, the French word for obstetrician. The English equivalent of the feminine form, accoucheuse, meaning midwife, has been used here as a more suitable translation.

[19] Here Kiesler uses the German word Kopien (copies), which at that time was a common technical term for photographic prints.

[20] Placed the prints in a machine and cut, deleted in pencil.

[21] More about this further on in the text.

[22] kind of, x’ed out on typewriter

[23] Kiesler is here referring to the photograph of the Bordeaux bottle used by Duchamp for the production of the photomontage on the front cover of View.

[24] he added, deleted in pencil.

[25] This is the original position in the typescript of the two sentences “Both of us agreed ...” and “I have just bought the tie, it's new”, which Kiesler circled with pencil and shifted — by a pencilled arrow — to a position in front of the previous sentence.

[26] Sentence beginning with He had ..., deleted in pencil.

[27] put it on, x’ed out on typewriter.

[28] He grinned, the photographer, x'ed out on typewriter.

[29] sharp, x'ed out on typewriter.

[30] smea, x ed out on typewriter.

[31] asked, x’ed out on typewriter.

[32] lines around the mouth, x'ed out on typewriter.

[33] would be, deleted in pencil, replaced by was.

[34] Marcel asked, x’ed out on typewriter.

[35] Here Kiesler uses the word Attendanten, his own German rendering of the English word attendants.

[36] The words in my coat pocket are written twice, deleted in pencil.

[37] About 7 foot, written twice, deleted in pencil.

[38] Just over two metres.

[39] He, x’ed out on typewriter; on the, x’ed out on typewriter.

[40] on the, x'ed out on typewriter.

[41] grasped the T[able], x’ed out on typewriter.

[42] to wipe the brown print dry, perhaps in order to ..., deleted in pencil.

[43] rolled, x’ed out on typewriter.

[44] assistant, x’ed out on typewriter.

[45] came, x’ed out on typewriter.

[46] Illegible deletion

[47] in, x’ed out on typewriter.

[48] 6.30, x'ed out on typewriter.

[49] Marcel and I sat, x’ed out on typewriter.

[50] This is the original position in the typescript of the sentences: “Marcel dashed through the hallway into the [other] room, saying: ‘I've got to be downtown at 7 o’clock.’”, which Kiesler circled with pencil and shifted — by a pencilled arrow — to a position in front of the two previous sentences.

[51] By “two of your pages” Duchamp is probably alluding to Kiesler’s planned article. The editors finally allocated six pages for Kiesler’s photomontage. Duchamp can hardly have been referring to this, as the printing of small photographs on the edge of a page would have had too negative an effect on the composition of the photomontage. Moreover, Kiesler did not receive the necessary photographic prints for the production of the photomontage in the centre of the magazine until he visited the photographer’s studio on January 13.

[52] The one of, x'ed out on typewriter.

[53] I looked at the print once again, deleted in pencil.

[54] and said, x’ed out on typewriter.

[55] Based on the elapsed time of three weeks, this visit must have taken place in the last week of December 1944, immediately after Duchamp’s and Kiesler’s meeting with the editors of View on December 22, 1944. Documentary evidence of this “check” may possibly be Kiesler’s biographical notes on Duchamp, which are kept in the archive of the Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna, as their style of writing is similar to that of interview notes. In the View issue of December 1944 (no. 4, Series IV, p. 8) the editors had announced that the “special number” on Marcel Duchamp, due for publication in March, would contain “the first complete survey of his life and work”. As Kiesler’s notes on Duchamp’s biography go far beyond the facts that were known at that time, it is certainly not unthinkable that he obtained these particulars in his interview with Duchamp with the specific aim of contributing something to the “completeness” of the survey of Duchamp’s life and work. What form this contribution was to take has remained unknown to this day. A typographical version of the notes has been published in: Kraus, Sonzogni: “Wanted: Original Manuscript on Marcel Duchamp”, 2003, in: http://www.toutfait.com/issues/volume2/issue_s/ collections/kiesler/kiesler.html

[56] which you had meticulously scraped together with both your hands, deleted in pencil.

[57] The mound of dust, x’ed out on typewriter.

[58] You then showed me, x’ed out on typewriter.

[59] was needed for coating the bottle, deleted in pencil.

[60] Kiesler had made a photomontage of Duchamp’s studio at 210 W 14 St and written the title “Poéme espace dédie a H(ieronymus) Duchamp” directly on the montage. It was published in the Marcel Duchamp Number of View, no. 1, 1945, p. 27.

[61] photographic reproduction altered by pencil to read photograph.

[62] Kiesler uses the English word appropriately in his German text.

[63] Here Kiesler mistakenly refers to Duchamp’s certificate of discharge, which is in fact the page of Duchamp’s military ID pass of 1905 giving his personal particulars. Duchamp was not conscripted in 1915 on account of a heart condition. Tomkins, Calvin: Marcel Duchamp. A Biography, New York, 1996, p. 167; Franklin, Paul B.: “Smoking Bottles”, in: Étant donné Marcel Duchamp, no. 10, 2011, p. 234.

[64] In his column “I Cover the Cover”, Peter Lindamood makes reference to Duchamp’s comments concerning the “failure of the much-experimented-with ray of light which was to have shot from page left across the planetarium illusion of the background, under the smoke”. View, 3. At the time of Kiesler’s report, however, the experiment had evidently not yet been made, and so there could not yet be any talk of its having been a failure.

[65] Here, and also in the following passage, Kiesler uses the English word screen in his German text.

[66] While 7 × 10 inches is a standard American format, the meaning here is not quite clear. Kiesler is evidently referring not to the format of the magazine — which is 9 ×12 inches — but to the format of the enlargement of the small halftone image that was to be used for the printing of the front cover of View.

[67] you, deleted in pencil.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES

I Was Waiting for Marcel (Frederick Kiesler)